This is part of a continuing series of articles on the European crises of the core and periphery. This column focuses on the causes of Ireland’s banking crisis. It begins by discussing what we know about modern financial crises in the West.

The leading cause of catastrophic bank failures has long been senior insider fraud. James Pierce, The Future of Banking (1991). Modern criminologists refer to these crimes as “control frauds.” The person(s) controlling seemingly legitimate entities use them as “weapons” to defraud creditors and shareholders. Financial control frauds’ “weapon of choice” is accounting. The officers who control lenders simultaneously optimize reported (albeit fictional) firm income, their personal compensation, and real losses through a four-part recipe.

- Grow extremely rapidly by

- Making poor quality loans at premium yields while employing

- Extreme leverage and

- Providing grossly inadequate provisions for losses for the inevitable losses

This recipe produces guaranteed, record reported income in the near term. In the words of George Akerlof and Paul Romer in their famous 1993 article – Looting: the Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit – accounting fraud is a “sure thing.” Even if the firm fails (“bankruptcy”) – which is no longer a sure thing given the bailouts of systemically dangerous institutions (SDIs) the CEO walks away wealthy (the “profit” part of the title). The use of “underworld” also demonstrates that Akerlof & Romer understood how important it was that the bank appears to be legitimate in order to aid the CEO’s “looting.”

Lenders engaged in accounting control frauds will tend to cluster in the most criminogenic environments. The most criminogenic environments have these characteristics

- Non-regulation, deregulation, desupervision, and/or de facto decriminalization

- Assets that lack easily verifiable market values

- The opportunity for rapid growth

- Extreme executive compensation based on short-term reported income

- Easy entry, and an

- Expanding bubble in the asset category that lacks easily verifiable market values

Individual accounting control frauds are exceptionally dangerous. The recipe makes them an engine that destroys wealth at prodigious rates. Control frauds cause greater financial losses than all other forms of property crime – combined. A single large accounting control fraud can cause losses so large that it renders a deposit insurance fund insolvent and causes a crisis. This happened in Maryland and Ohio “thrift and loans” in the mid-1980s. The failure of a single accounting control fraud in each state caused the collapse of the entire privately insured thrift and loan system in each state.

Accounting control frauds are also criminogenic. I will only discuss two ways in which these frauds are criminogenic and mention a third way in passing. The first concept is the “Gresham’s dynamic.” In this context, that term refers to a perverse dynamic in which those that cheat gain a competitive advantage over their honest rivals. This twists “competition” and “private market discipline” into perverse forces that can drive honest firms and professionals from the market place. There are three primary variants of Gresham’s dynamics that are criminogenic. Accounting control frauds’ record reported profits and their leaders’ extreme compensation inherently create Gresham’s dynamics with respect to rival firms and senior officers. The CEOs who lead accounting control frauds can intentionally create Gresham’s dynamics among their employees, customers, and agents in order to suborn them into becoming fraud allies. Accounting control frauds that are lenders can also create an undesired Gresham’s dynamics among third parties. The fraud recipe requires them to render their underwriting ineffective and to suborn their internal and external “controls.”

The second criminogenic aspect of accounting control frauds is that it can hyper-inflate asset bubbles. This is easier to do in smaller economies such as Ireland and Iceland, but the current crisis has shown that epidemics of accounting control fraud can hyper-inflate bubbles even in the world’s largest economy.

The third criminogenic aspect is that accounting control frauds can cause crippling “systems capacity” problems that make it less likely that the regulators and prosecutors will respond effectively to the frauds. I will discuss this third aspect in greater detail in future essays.

Economists have known for over 40 years about the role of control fraud in producing perverse Gresham’s dynamics.

“[D]ishonest dealings tend to drive honest dealings out of the market. The cost of dishonesty, therefore, lies not only in the amount by which the purchaser is cheated; the cost also must include the loss incurred from driving legitimate business out of existence.” George Akerlof (1970).

I’m writing this in Dublin, so it is fitting to give credit to the insights of an Irish genius whose views on the same subject predate Akerlof’s, for they were published in 1726 while he was in Dublin.

The Lilliputians look upon fraud as a greater crime than theft. For, they allege, care and vigilance, with a very common understanding, can protect a man’s goods from thieves, but honestly hath no fence against superior cunning. . . where fraud is permitted or connived at, or hath no law to punish it, the honest dealer is always undone, and the knave gets the advantage.

Swift, J. Gulliver’s Travels, London, Penguin (1967) p. 94. See Levi, M. The Royal Commission on Criminal Justice. The Investigation, Prosecution, and Trial of Serious Fraud. Research Study No. 14, London, HMSO (1993) p. 7.

Swift’s words should be etched on every building housing a financial regulator. The regulatory cops on the beat’s principal function is to reduce this Gresham’s dynamic and help honest firms prosper by stopping the frauds.

Akerlof wrote about Gresham’ Law in his famous article on markets for “lemons,” which led to the award of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001. As the language he used makes clear (“dishonest,” “cheated,” and “legitimate”), he was describing what criminologists now refer to as a “control fraud.” The seemingly legitimate firm gains a competitive advantage over honest rivals by defrauding the consumer about the quality of the goods. That is an example of anti-customer control fraud. If a dishonest used car dealer takes advantage of his superior information about the quality of the car (“asymmetrical information”) to purchase defective cars (“lemons”) for a low price and sells them as purported high quality cars for the market price for high quality cars he will have a substantial competitive advantage over any honest rival. Market forces will tend to drive the honest competitors out of the market.

Accounting control fraud, by contrast, does not create a competitive advantage. The recipe for a lender, for example, is a recipe for losing massive amounts of money. The rational, legitimate bank under any neoclassical model would be overjoyed to see its competitors committing suicide by making massive amounts of bad loans. Where then does the Gresham’s dynamic arise for accounting control frauds? The answer is executive compensation and survival. It is now common for executives to “earn” exceptional compensation if they report that the firm has “earned” exceptional income. In a reasonably competitive market it is the rare CEO and CFO who should be able to obtain highly supra-normal profits in any particular year. However, the fraud recipe produces guaranteed, record reported firm income in the short-term. Once accounting control frauds begin to operate in an industry their senior officers will receive extraordinary compensation. Honest CFOs, overwhelmingly, should fail to attain supra-normal profits in any particular year. That means that their bonus, their peers’ bonuses, and their CEO’s bonuses will be far lower than they could be, and often far less than the dishonest executives receive. The honest CFO has a direct financial incentive in terms of his own compensation to adopt the fraud recipe that is making his rival’s wealthy. More importantly, the honest CFO will fear that his CEO will fire him if he cannot match the accounting control frauds’ record reported income. The CEO that fails to match the reported record profits of his fraudulent rivals does not simply lose millions of dollars in compensation; he may also lose his job through a takeover (or, more rarely, through a board of directors revolt). Modern executive compensation causes accounting control fraud to produce an inherent, powerful Gresham’s dynamic among other firms in the same industry.

The CEOs that lead accounting control frauds also create deliberate Gresham’s dynamics in order to aid their frauds. Fraudulent CEOs seek to suborn their colleagues, customers, agents, “controls,” and “independent” professionals in order to make them fraud allies. They do so through the full gamut of psychological and material rewards. This produces “echo” epidemics of fraud in these other contexts. I have written about these echo epidemics extensively so I will only provide a few examples here. If a CEO bases his loan officers’ compensation on loan volume, not quality, then dishonest loan officers will become far better compensated. If a CEO simultaneously debases underwriting and internal controls this perverse incentive and result will be greatly increased. If the CEO causes the bank to make liar’s loans and creates a compensation system for loan brokers that increases with (1) loan volume, (2) lower debt-to-income ratios, and (3) lower loan-to-value (LTV) ratios (to name only three common characteristics) then the loan brokers will produce fraudulent loan applications with grossly inflated “stated” incomes and fraudulent inflated appraisals (which is also done by creating a Gresham’s dynamic in the hiring and compensation of appraisers). If the CEO “shops” for compliant audit partners and credit rating agencies then the CEO will generate a Gresham’s dynamic that will permit him to suborn purported “controls” and obtain their “blessing” for grossly inflated market values. The fraudulent CEO finds these controls’ reputation valuable in committing accounting fraud. The CEO can use a similar perverse incentive to induce many borrowers to knowingly file false loan applications. An honest banker would not create such Gresham’s dynamics because it would harm the bank. Collectively, the fraudulent CEOs at hundreds of nonprime lenders deliberately generated these perverse incentives in order to maximize the four-part recipe for fraudulent reported income. This was guaranteed to make them wealthy – quickly. It also guaranteed massive losses to the firms, the customers, and the government.

Collectively, the primary and echo epidemics of accounting control fraud produced staggering amounts of fraud. The incidence of fraud in liar’s loans in reported studies is 90% and above. By 2006, one-half of loans called subprime were also liar’s loans. Collectively, nonprime loans in the U.S. were enormous under any estimate (though the estimates vary seriously).

The third form of Gresham’s dynamic is not desired even by fraudulent CEOs. When a dog lies down with fleas it comes up with fleas. Firms engaged in accounting control fraud have grossly deficient underwriting and controls and, over time, they increasingly select for the officers and employees who are willing to deliberately make and approve bad loans. The best bankers leave. Without strong underwriting and controls to restrain them, the worst bankers are increasingly tempted to engage in fraud for their own account (instead of the CEO’s).

Accounting control frauds are particularly well designed to cause bubbles to hyper-inflate. First, the recipe’s initial ingredient is extreme growth.

Second, control frauds can sustain that extreme growth for a considerable time period. A business strategy that depends on extreme growth through making high quality loans is inherently limited, particularly in a reasonably competitive, mature market. An individual firm that seeks to grow extremely rapidly by making good loans would have to “buy market share” by reducing its yield. Its competitors would match its lower interest rates. The end result would be that lenders’ income would fall. Even if a firm could grow extremely rapidly by making good loans, a lending industry could not do so. (This is known in logic as the “fallacy of composition.”) The industry could grow by making good loans at roughly the rate of GDP growth – far less than is required to hyper-inflate a bubble.

This is why the second ingredient in the fraud recipe is so important. There are tens of millions of potential home owners who cannot afford to buy a home. A lender can grow rapidly and charge these unceditworthy borrowers a premium yield. Better yet, many lenders can follow this same strategy. Best of all, as more lenders follow the fraud recipe it works even better to make the CEO wealthy. The faster the growth in lending, the faster and greater the bubble hyper-inflates. This allows the lenders to refinance the bad loans and delay loss recognition for years. The saying in the industry is “a rolling loan gathers no loss.” (Lenders also structured loans to be negative amortizing in order to delay the inevitable defaults.) Every year the fraud continued could add millions of dollars to the CEO’s wealth.

Third, as I explained above, accounting control frauds will tend to cluster, particularly if entry is relatively easy, in particular asset categories, industries, and regions that are most criminogenic. This clustering makes accounting control fraud more likely to hyper-inflate a bubble.

Fourth, because they are frauds, lenders will often continue to grow rapidly even into the teeth of a glut. This makes them particularly important in sustaining the life of bubbles.

Fifth, some kinds of assets are exceptionally good at hyper-inflating bubbles. The U.S. experienced simultaneous bubbles in residential and commercial real estate (CRE), but the residential bubble caused far greater losses because it was the largest bubble in history and because liar’s loans were such an ideal fraud mechanism. Even the U.S. anti-regulators would have balked at making CRE loans without any meaningful underwriting. CRE loans pose unique dangers in causing CRE bubbles to hyper-inflate. (CRE bubbles and residential real estate bubbles can interact because they may both compete for the same land.) Single family dwellings have some potential restraints because one can estimate demand for housing reasonably well. CRE has few restraints. It is frequently speculative (it is not preleased to prospective tenants). CRE loans can be massive. If the bubble hyper-inflates the initial large CRE borrowers will report few losses and record profits from any sales. The bank can then lend exceptional amounts of money to the successful developers on the basis of their appreciating real estate. Concentrations of credit can become extraordinary.

Sixth, bubbles are much easier to hyper-inflate in smaller nations. The Irish real estate bubble is typically described as over twice the (relative) size as the U.S. Spain’s real estate bubble is off the charts even though its economy is far larger than Ireland’s. The nonprime sector, which was endemically fraudulent, was capable of hyper-inflating the largest bubble (in absolute terms) in history in the world’s largest economy. The effect was to right-shift the demand curve for housing – for a time – by lending to those who would often be unable to repay their loans so that they could buy homes at prices greatly inflated by a bubble.

(For estimates of the size of the nonprime market see William Poole, Reputation and the Non-prime Mortgage Market (July 20, 2007) (available on line at the FRB of St. Louis). Note that the issue is not the absolute number of nonprime loans but the additional loan volume represented by nonprime loans made as the bubble hyper-inflated. Nonprime loans increasingly became the marginal loan.)

The role of an epidemic of accounting control fraud in hyper-inflating a regional CRE bubble in the Southwest during the S&L debacle is explained in Akerlof & Romer (1993), the report of the National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery and Enforcement (1993), and The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One (Black, W. 2005)

The central points of the preceding discussion are that if a nation suffers a series of catastrophic banking failures the single most likely explanation for them is accounting control fraud; particularly if the crisis involves a hyper-inflated bubble. Naturally, when Ireland decided to investigate the causes of its crisis it hired a non-investigator and instructed him not to investigate whether the leading cause of catastrophic bank failures and hyper-inflated bubbles had occurred. Here is how Mr. Nyberg explained the matter:

“The mandate of the Commission did not include investigating possible criminal activities of institutions or their staff, for which there are other, more appropriate channels. Under the Act, evidence received by the Commission may not be used in any criminal or other legal proceedings.” (Nyberg 2011: 11)

“The Commission has not investigated any issues already under investigation elsewhere. Instead, the Commission used its limited time and resources to investigate, as its Terms of Reference specified, why the Irish financial crisis occurred.” (Nyberg 2011: 11)

Yes, you read it correctly. Because he was barred from investigating fraud (which was outside his expertise), he investigated “why the Irish financial crisis occurred.” He knew, of course, without investigation or expertise in detecting fraud, that the crisis did not occur because of insider fraud even though insider fraud is the most common cause of such crises. Nyberg’s report is the third report Ireland has paid for (at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars). It contains no essential new facts not already known from the prior reports – because it did not conduct any real investigation. It reads like a defense lawyer’s brief for the senior management of the failed Irish banks. Ireland paid Nyberg large amounts of money to make it far harder to prosecute or even sue the CEOs that destroyed the Irish economy. This is significantly insane.

So, what did cause the crisis according to Nyberg? Even Nyberg admits he has no coherent explanation. The next two sentences epitomize his report:

“Even with the benefit of hindsight, it is difficult to understand the precise reasons for a great number of the decisions made. However, it would appear that they generally were made more because of bad judgment than bad faith.” (Nyberg 2011: 11)

Got it? Nyberg can’t explain the CEOs’ decisions. But not to worry, for “it would appear” that they “generally” were made “more” “because of bad judgment than bad faith.” Here’s why this cloud of vagueness matters. If the managers acted in bad faith they will be at least liable for the damages in a civil or administrative action and quite possibly criminally liable. The damages the managers caused are so massive relative to their assets that it almost certainly does not matter whether they “generally” caused injury through bad judgment. The times they did act in bad faith would subject them to greater civil liability than their assets. It also doesn’t much matter that “more” of the damage they did was due to bad judgment than bad faith. A mixture of bad faith and bad judgment would subject them to crushing civil liability and criminal prosecution. So, for all the money it spent, Ireland deserved to be told where Nyberg found that the officers acted in bad faith so that it could guide the process to hold them appropriately accountable.

“Indeed, a fair number of decision-makers appear to have followed personal investment policies that show their confidence in the policies followed by “their” institution at the time. Such faith usually produced large personal, financial and reputational losses.” (Nyberg 2011: 11)

This is too vague and likely (it’s so vague it’s impossible to be certain) evidences a failure to understand accounting control fraud. “A fair number of decision-makers” is a doubly vague phrase and it is illogical as an argument. What’s a “fair number?” Which “decision-makers” acted in this manner? The fact that some decision-makers lost money on some unspecified investment does not indicate that the others had the same views (assuming those views somehow negated intent). More basically, it is common for accounting control frauds to suffer losses. They are not geniuses. I quote Nyberg below about how “easy” it was for the officers to maximize their personal compensation by making bad loans. No one knows when a bubble will collapse, so the officers controlling fraudulent lenders often stay in investments too long and suffer personal losses. Those losses do not negate a criminal intent.

How would a real investigation that had expertise look at the facts Nyberg found?

“The [compensation] models, as operated by the covered banks in Ireland, lacked effective modifiers for risk. Therefore rapid loan asset growth was extensively and significantly rewarded at executive and other senior levels in most banks, and to a lesser extent among staff where profit sharing and/or share ownership schemes existed.” (Nyberg 2011: 30)

What can we infer from these facts? The controlling officials at the worst Irish banks paid themselves, their senior officers, and even their staff largely on the basis of loan volume – irrespective of the soundness of the loans. This is suicidal for a mortgage lender because it creates intense, perverse incentives to make bad loans. It leads to extremely rapid growth through making increasingly bad loans. This produces severe “adverse selection.” Adverse selection in these lending fields produces a negative expected value of lending – the lender will lose money and fail. Nyberg has established that the banks followed the first two ingredients of the recipe for maximizing short-term (fictional) reported accounting income – and the controlling officers’ compensation.

“Targets that were intended to be demanding through the pursuit of sound policies and prudent spread of risk were easily achieved through volume lending to the property sector. On the other hand, most banks also included performance factors in their models other than financial growth.” (2011: 30)

Focus on the word “intended.” This is a characteristic flaw of Nyberg’s report. The bonus targets were not “intended to be demanding” much less “through the pursuit of sound policies.” Nyberg provides nothing in his report that supports his claim that senior managers “intended” to create a “demanding” hurdle before they could receive exceptional compensation. Similarly, he provides no support for the claim that the senior managers “intended” to assure “sound policies” by creating a compensation system that was certain to produce unsound policies, consistently produced unsound policies, was known by the senior managers to produce unsound policies, and was repeatedly modified to encourage ever more unsound policies. Nyberg’s report repeatedly refutes his claims. Nyberg never identifies the mythical, unidentified senior people who he purports had such an intent. The real factual takeaway is that the officers and staff could, respectively, get wealthy and well-off “easily” by following the first two ingredients of the recipe that maximizes fictional bank income and real compensation.

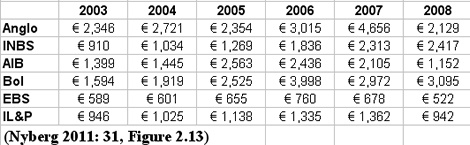

“Rewards of CEOs reached levels, at least in some cases, that must have appeared remarkable to staff and public alike. It is notable, that proportionate to size, the CEOs of Anglo and INBS received by far the highest remuneration of all the covered bank leaders.” (Nyberg 2011: 30)

No, the compensation the CEOs caused “their” banks to pay them as “rewards” for making exceptionally bad loans that were destroying the banks and Ireland’s economy did not “appear” “remarkable” – they were remarkable. Recall that Nyberg concedes that the managers “easily” obtained remarkable compensation not through any skill but rather through making loans without regard to risk. Making loans with acute, expert regard to risk is the core skill of a lender. Why would it ever make sense to pay CEOs remarkable compensation for making bad loans chosen by the CEO because they maximized his wealth? Nyberg provides this chart of CEO compensation.

The recipe was a “sure thing” for the controlling managers. They made sure that they could “easily” and quickly become wealthy. Nyberg finds a Gresham’s dynamic, but offers a naïve view of how it operates because he uncritically accepts the self-serving claims of “bank management and boards.”

“Bank management and boards in some of the other covered banks feared that, if they did not yield to the pressure to be as profitable as Anglo, in particular, they would face loss of long-standing customers, declining bank value, potential takeover and a loss of professional respect.” (Nyberg 2011: v)

Anglo was not “profitable” during the bubble while it was making loans without regard to their risk. It was creating net liabilities (losing money) when it lent – it simply was not recognizing the reality. Anglo was destroying itself. The other managers may have had some fears of a hostile takeover, but the Nyberg report shows that they were driven primarily by their desire to maximize their personal compensation. Nyberg seems to credit the claim of “a number of bankers” that compensation did not drive managers’ decisions.

“Nevertheless, it was claimed by a number of bankers that management and staff were not motivated by compensation alone. Most would compete, it was claimed, as they had during the previous period of lower compensation, on the basis of natural competitiveness and professional pride.” (Nyberg 2011: 31)

This passage is wondrously incoherent. No one thinks humans are “motivated by compensation alone.” Ego, status, and prestige, for example, are often powerful motivators, but this increases the criminogenic nature of perverse compensation for extreme compensation is often the entrée in the modern world to increased status. “Natural competitiveness” almost certainly compounded these perverse incentives as individuals, particularly males, competed to be the top producers of disastrously bad loans that were destroying Ireland. The top producers got paid the most and had higher status. What “professional pride?” Nyberg’s report shows the opposite – the perverse compensation had its typical effect in destroying bank professionalism and integrity.

“Over time, managers known for strict credit and risk management were replaced; there is no indication, however, that this was as a result of any policy to actively encourage risk-taking though it may have had that effect.” (Nyberg: v)

“In addition, there were some indications that prudential concerns voiced within the operational part of certain banks may have been discouraged. Early warning signs generated lower down in the organisation may in some cases not have reached management or the board. If so, the pressure for conformity in the banks has proven to be quite expensive.” (Nyberg: v)

“The few that admitted to feeling any degree of concern at the change of strategy often added that consistent opposition would probably have meant formal or informal sanctioning.” (Nyberg 2011: v)

Nyberg has described the Gresham’s dynamic characteristic of control frauds, but suicidal for an honest bank. The best people are forced out. Those that remain go along with the CEOs dictates. Consider the first quotation, another Nyberg classic. Anybody known for effective underwriting was “replaced.” We’ll return to Nyberg’s claim that there was “no indication” this was designed to encourage making bad loans and his use of “risk-taking” as a euphemism.

Now we add the second quotation. Could we make a report any more vague and useless? “There were some indication that prudential concerns voiced within the operational part of certain banks may have been discouraged.” Nyberg has just written that those who rejected bad loans were “replaced.” That “discouraged” voicing operational concerns. We’ll return to the remainder of that quotation.

The third quotation completes the inevitable result of replacing those who refuse to make the bad loans. “Few” would even admit years later that they felt even “concern” about making loans without regard to risk (again, this is suicidal for mortgage lenders). Even those few said nothing because they believed opposition to the CEO’s plan would lead to them being “sanction[ed].” Once more, Nyberg has described the kind of criminogenic environment that the CEO generates to create “echo” fraud epidemics throughout the organization.

We can now complete the discussion of the first quotation. Here it is again:

“Over time, managers known for strict credit and risk management were replaced; there is no indication, however, that this was as a result of any policy to actively encourage risk-taking though it may have had that effect.” (Nyberg: v)

What would it take before Nyberg can find an “indication?” Does he expect that senior managers are going to tell him that they “replaced” Sean for the purpose of “actively encourage[ing] risk-taking?” They got rid of people who rejected bad loans. They “discouraged” people from raising prudential concerns. The staff feared that it would be “sanctioned” if it raised concerns and this Gresham’s dynamic was so effective that “few” of the remaining staff would even admit to having any concern about a suicidal lending policy.

More fundamentally, none of this – on the facts found by Nyberg – has anything to do with “risk-taking” as we conventionally use that term in finance and economics. Akerlof & Romer agree with us (criminologists) – accounting control fraud is a “sure thing.” The massive executive compensation it creates is a “sure thing.” The supposedly exceptional bank “income” or loan volume necessary to maximize one’s bonus is typically “easily” met by making loans without regard to creditworthiness. The accounting fraud strategy that relies on making loans without regard to creditworthiness is also suicidal. “Risk-taking” at banks involves exactly the opposite behavior. Underwriting is the process of identifying, pricing, and managing bank lending risk. Underwriting is what Nyberg found that the Irish bank CEOs eviscerated.

Nyberg eagerness to offer apologies for the controlling managers is displayed again in the second quotation.

“In addition, there were some indications that prudential concerns voiced within the operational part of certain banks may have been discouraged. Early warning signs generated lower down in the organisation may in some cases not have reached management or the board. If so, the pressure for conformity in the banks has proven to be quite expensive.” (Nyberg: v)

I focus here on the last two sentences. The implicit premise of these sentences is that “management or the board” would have listed to “prudential concerns” from the staff about management’s policy of lending without regard to creditworthiness in order to maximize management’s compensation. Nyberg presents nothing that would support this implicit premise. His report disproves the premise. It was “management” that created the loan policy. It was “management” that “replaced” the officers and staff who opposed the policy. The “few” staffers left that even had a “concern” about the suicidal policy kept their mouths shut because they were afraid of being “sanctioned” by management. No one was better positioned than “the board and management” to know that creating a compensation system that rewarded making mortgage loans regardless of creditworthiness was suicidal. We have understood adverse selection in banking for hundreds of years. No junior staffer needed to tell the board and management that the compensation and lending policies were suicidal for the bank and fabulous for management. If more staffers had said no to the bad loans then the management would have “replaced” more staffers until the Gresham’s dynamic was all-encompassing at the staff level.

Nyberg conclusion about the perverse role of compensation brings out yet another apology for senior management.

“Financial incentives were unlikely to have been the major cause of the crisis. However, given their scale, such incentives must have contributed to the rapid expansion of bank lending.” (2011: 31)

His own report refutes his apology. Nyberg actually finds that the financial incentives were (1) perverse, (2) exceptionally lucrative to the controlling officers, and (3) decisive in determining the conduct that destroyed the banks and Ireland’s economy.

“Occasionally, management and boards clearly mandated changes to credit criteria. However, in most banks, changes just steadily evolved to enable earnings growth targets to be met by increased lending.” (Nyberg 2011: 34)

Nyberg found that compensation drove the banks’ “credit criteria.” In plain English, that means that the banks made continually worse loans it new were less likely to be repaid in order to maximize the officers’ compensation. Nyberg found that the banks’ controlling officers chose their personal compensation over the quality of bank loans. Nyberg uses a lot of jargon, but he concedes the essential nature of underwriting standards.

“The core principles, values and requirements governing the provision of credit are contained in a bank’s credit policy document which must, as a regulatory requirement, be approved at least annually by a bank’s board. The policy defines the risk appetite acceptable to the bank and appropriate for the markets in which the bank operates….”

“The purpose of such a credit policy is to set out clearly, particularly for lenders and risk officers, the bank’s approach to lending and the types and levels of exposures to counterparties that the board is willing to accept.” (2011: 31)

In this passage, however, Nyberg resorts to clear writing.

“The associated risks appeared relevant to management and boards only to the extent that growth targets were not seriously compromised.” (Nyberg 2011: 49)

Nyberg finds that the banks’ credit policies were fictions – fictions that repeatedly yielded to the necessity of maximizing the officers’ compensation.

“[A]ll of the covered banks regularly and materially deviated from their formal policies in order to facilitate rapid and significant property lending growth. In some banks, credit policies were revised to accommodate exceptions, to be followed by further exceptions to this new policy, thereby continuing the cycle.”

One of the predictions that flows from the recipe for maximizing fictional short-term accounting income is that over time loan quality is likely to deteriorate as lending is expanded to increasingly less creditworthy borrowers. Nyberg found that this happened.

“As all banks had effectively adopted high-growth strategies (IL&P less so), the aggregate increase in credit available could not be fully absorbed by good quality loan demand in Ireland. Banks had two options to remedy this; diversify their lending into other markets or relax lending standards.” (Nyberg 2011: 34)

“[S]ubstantial numbers of new loans were made in Ireland. By implication, credit standards fell. The lowering of standards manifested itself as both a reduction in minimum accepted credit criteria and (more subtly) as an increase in accepted customer and property leverage.” (Nyberg 2011: 34)

Note that Nyberg also found that the Irish banks could not grow extremely rapidly by making good quality loans. They found, consistent with the predictions of control fraud theory, that the banks moved to increasingly poor quality loans at premium yields.

Nyberg then finds that the banks violated both their own underwriting limits and banking rules. He confirms a common criminological insight – the continued violation of the law leads to “neutralization” that diminishes any perceived immorality.

“The resulting asset growth meant that internal lending limits (both sector and large exposure limits) were exceeded. Regulatory sector limits in some banks were also exceeded, both prior to and during the Period. Gradually, as such excesses became more frequent, they were viewed with less seriousness.” (Nyberg 2011: 34)

Nyberg found related facts consistent with the predictions of control fraud theory. First, accounting control frauds often continue to lend and seek to grow rapidly into the teeth of a glut because they are quasi-Ponzi schemes. Second, it is far easier to grow by making bad loans than good loans. This is one of two places in the report that he uses the word “easily” to explain that the four-part recipe was a “sure thing” – guaranteed to maximize the CEO’s compensation.

“The demand for Development Finance was so strong over the Period that bank and individual growth targets were easily met from this sector. Both of the bigger banks continued to lend into the more speculative parts of the property market well into 2008, even though demand for residential property (a major end-user) had begun to decline by the end of 2006.” (Nyberg 2011: 35-36)

Nyberg also found, consistent with control fraud theory, that the Irish banks were major contributors to the hyper-inflation of the Irish real estate bubbles.

“Thus, banks accumulated large portfolios of increasingly risky loan assets in the property development sector. This was the riskiest but also (temporarily) the easiest and quickest route to achieve profit growth.” “Credit, in turn, drove property prices higher and the value of property offered as collateral by households, investors and developers also.” (Nyberg 2011: 50)

Nyberg found the clustering aspect of accounting control fraud that helps cause bubbles to hyper-inflate.

“High profit growth was the primary strategic focus of the covered banks…. Since the potential for high growth (in assets) and resultant profitability in Ireland were to be found primarily in the property market, bank lending became increasingly concentrated there.” (Nyberg 2011: 49)

Nyberg concedes that the controlling officers could only believe that their lending policies were not suicidal if they adopted an irrational belief contrary to everything we know about finance. The CEO simply had to believe that:

“As long as there was confidence that prices would always increase and exit finance was available, an upward spiral of lending and property price increases was maintained.” (Nyberg 2011: 50)

Yes, if prices always increase then banks might survive making bad loans. Making bad loans would still be irrational, however, for an honest lender because they could still make more money by making good loans.

The third ingredient in the four-part recipe is extreme leverage. Nyberg is very weak on this point. His findings demonstrate that several of the Irish banks were massively insolvent for years while they continued to grow rapidly by making bad loans. When equity is negative, leverage ceases to be a meaningful ratio.

Nyberg is particularly damaging on the fourth ingredient – grossly inadequate loss reserves. The view he takes of international accounting standards would create a perfect crime. Nyberg is disturbed about that result, but he does not understand that if he is right he is describing a monstrous loophole that most of the bank CEOs in the world can use to loot “their” banks with impunity.

“In the benign economic environment before 2007, the banks reduced their loan loss provisions, reported higher profits and gained additional lending capacity. The banks could no longer make more prudent through-the-cycle general provisions, or anticipate future losses in their loan books, particularly in relation to (secured) property lending in a rising property market.” (Nyberg 2011: 42)

A record financial bubble that misallocates billions of dollars of credit and assets and causes a severe economic crisis is not “benign.” The Irish bubble stalled in 2006. The Irish banks that Nyberg studied would not have made “more prudent ‘through-the-cycle’ general [loss] provisions” absent changes in the international accounting rules. Nyberg is again displaying his apologist for management instinct. Elsewhere, Nyberg, refutes Nyberg. Note that he found that not establishing loss reserves increased the banks’ reported profits and its ability to grow. That meant it increased the top managers’ compensation. Indeed, as I will explain, had the banks complied with the principles underlying the international accounting standards the banks would have had to report that they were insolvent and the controlling officers would have lost their jobs and incomes.

“The higher reported profits also enabled increased dividend and remuneration distributions during the Period. All of this led to reduced provisioning buffers….”

“From 2005 the banks’ profits, capital and lending capacity were enhanced by lower loan loss provisioning while the benign economic conditions continued. (Nyberg: 55)

“As a consequence of not making this level of loan loss provisions [1.2% of loans], increased accounting profits effectively provided additional capital of up to €3.5bn to the covered banks. This, in turn, increased their capacity to lend by over €30bn.” (Nyberg 2011: 43)

Again, failing to provide remotely adequate ALLL did not provide “additional capital” to the Irish banks. It created (fictional) increased reported income and capital to the banks, which led to larger compensation to the officers and increased bank growth and leverage. None of this should have been permitted under a “principles-based” international accounting standard – particularly when the banks were engaged in the unprincipled exploitation of an accounting standard designed to create another variant of the abuse the international accounting standard was designed to prevent.

International accounting rules were promoted largely on the basis of their asserted superiority over generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and their principal asserted advantage was that they were principles-based. The idea was that the effort to specify and forbid every possible abuse (which was supposedly GAAP’s approach) invariably lead to unmanageable audit standards that could always be evaded. Principles-based audit standards would be far more concise and better prevent abuses because the auditors would be responsible for adhering to those principles rather than pursuing arcane, technical evasions of GAAP. One of the differences between GAAP and the international accounting standards was the treatment of allowances for loan and lease losses (ALLL). The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the international standards setting bodies shared a concern about “cookie jar reserves.” A common abuse was to use improperly the ALLL allowances as a reserve that could be called on whenever needed to “make the number” and ensure that the firm’s stock price (and the senior executives’ compensation) not be reduced. The SEC filed a complaint asserting, for example, that Freddie Mac’s engaged in securities fraud by hiding gains in good years through inappropriately increasing its ALLL account and reducing the ALLL allowance in bad years sufficiently to make the analysts’ quarterly predicted earnings per share forecast.

GAAP revised the ALLL provision through a principles-based approach designed to prevent two abuses – cookie jar reserves and the fourth ingredient of the accounting control fraud recipe. The specific language of the international accounting standards provision dealing with allowances for loan losses did not discuss explicitly the second form of accounting fraud. Instead, it aimed to kill “cookie jar reserves” as an intolerable abuse. The purpose of the rule was to prevent the officers controlling a firm from manipulating the allowance for losses for the purpose of inflating the share price and the officers’ compensation. Nyberg, without discussion of any alternative interpretation that would actually accord with the anti-fraud principle underlying the international rule, asserts that it must be interpreted to facilitate accounting control fraud. He then asserts that this rule is the reason the Irish banks have inadequate allowances for losses.

“As the global crisis developed from mid-2007, the banks were constrained by these incurred-loss rules from making more prudent loan-loss provisions earlier, and the auditors were restricted from insisting on such earlier provisioning.” (Nyberg: 55)

“The composite provisioning level for the covered banks at end 2000 was 1.2% of loans…. If this 1.2% provisioning level had been applied at the 2007 year end by the covered banks, aggregate provisions would have increased by approximately €3.5bn (i.e. from the €1.8bn actual to €5.3bn).” (Nyberg 2011: 43)

“[T]he incurred-loss model [IAS 39] also restricted the banks’ ability to report early provisions for likely future loan losses as the crisis developed from 2007 onwards.” (Nyberg 2011: 42-43)

Nyberg’s interpretation would create the perfect insider bank fraud – throughout most of the world. It would destroy the anti-fraud principle underlying the international accounting standard he cites. There are three key, related lessons to be learned from his argument. One, the international accounting standards setting bodies should promptly and authoritatively reject his interpretation of IAS 39. Two, alternatively, if the bodies adopt the principle that IAS 39 should be interpreted to defeat its underlying anti-fraud principle, then they should change the rule on an emergency basis. Three, in any event, Nyberg’s story of a poor little management and Big 4 audit firm trying to do the right thing about allowances for loan losses but being stymied by IAS 39 is a fantasy and Nyberg’s apologies for the managers are beyond embarrassing.

I leave to the reader the reason a principles-based accounting system should be interpreted in a manner that supports rather than defeats the underlying anti-fraud purpose of the rule. But what if the accountants or the international accounting standards setting boards choose to defeat the anti-fraud purpose of the rule? That would create the perfect fraud. Some numbers may help. Recall that Nyberg’s fundamental factual finding is that the banks lent without regard to risk whenever considering risk conflicted with the imperative to maximize the controlling officers’ compensation. That is the heart of accounting control fraud. Assume that Bank A subject to the international accounting standards grows exceptionally rapidly, while employing extreme leverage, by lending to states and localities at 15% with a term of 30 years. Assume that the 15% yield embodies 3% less than an appropriate yield premium for the risk of lending to states and localities because of their current financial distress. Bank A only lends to states and localities with relatively good credit, so defaults are unlikely to become large in the near term. Assume that Bank A can borrow at 3% and has general and administrative expenses of 2%. Statistically, Bank A loses money with every loan it makes under this program. The appropriate allowance for loan losses, under GAAP, would be over 15%. If Bank A established the appropriate allowances for losses on these loans it would be admitting that it was losing money on the loans. Under the international accounting rules (assuming they are interpreted to defeat the allowance for loan loss provisions’ purpose), the allowance would be close to zero in the early years because Bank A would experience very few losses. The combination of the extreme nominal yield (15%), the delay in losses, and the virtually nonexistent allowance for loan losses, produces exceptional reported income – even though in economic substance Bank A is losing money when it makes the loans. With modern executive compensation, Bank A’s controlling officers have a “sure thing” – they will receive exceptional compensation and quickly become wealthy. Bank A will eventually fail, but the CEO will walk away rich and with legal impunity from any claim for securities fraud. The internal accounting rules, if so interpreted, will create a perfect crime – one that Nyberg aptly called “easy.” It takes no great skill to make bad loans.

Recall what even Nyberg admits in his specific factual findings (though rarely his conclusions) was actually going on at these Irish banks. They loaned without regard to risk in order to maximize the controlling officers’ compensation. The amount and degree of bad loans they made grew over time and became staggering. Losses at the worst Irish banks are roughly 60% of total (fictional) assets. The banks typically continued to lend into a bubble they knew had collapsed over a year earlier to people they knew were uncreditworthy. (They made the loans largely to cronies and borrowers they knew could not repay the loans because they were massively insolvent given the collapse of the bubble. They made the new loans largely to give those uncreditworthy borrowers cash to delay defaults on their prior loans.) The ALLL that Anglo would have needed to avoid recognizing additional losses was not 1.2% — it was 60%.

Nyberg completes his fantasy about the banks’ managers with this epic claim:

“In the competitive market, many property loans were made at margins of less than 1% per annum. A composite year end provisioning level at the 2000 level of 1.2% might have caused the banks to reconsider the amount of low margin property lending and might have led to more appropriate pricing for risk.” (Nyberg 2011: 43)

Ireland’s banks did not operate in a “competitive market.” Yes, there was some competition for borrowers, but in a real market none of the banks would have competing to see who could make the largest money-losing loans. If the Irish banks made “many” property loans at margins of less that 1% then we need to have another discussion. Banks that make “many” property loans at margins of less than 1% fail even if they make exceptionally safe loans. The Irish banks were making loans sure to fail.

“The demand for Development Finance was so strong over the Period that bank and individual growth targets were easily met from this sector. Both of the bigger banks continued to lend into the more speculative parts of the property market well into 2008, even though demand for residential property (a major end-user) had begun to decline by the end of 2006.” (Nyberg 2011: 35-36)

Elsewhere, Nyberg aptly refers to CRE lending as the “riskiest” lending. He found that it got progressively worse before 2007 – much worse. He found, as I have just cited, that the banks went heavily into the “speculative parts of the property market well into 2008” well after the bubble collapsed. Speculative CRE is exceptionally risky – when done (1) in a favorable economic environment, (2) with superb underwriting, (3) with careful limits on concentrations within sectors and in terms of loans to one borrower, (4) and to borrowers who are successful and not in financial distress, while (5) avoiding any conflicts of interest such as insider loans or loans to cronies. The Irish banks were zero for five on these characteristics.

No one was holding a gun to the heads of the Irish banks. There’s no reason why an honest bank would have made “many” property loans at margins below 1% to pristine credits in great economic times. The actual CRE developers they were lending to in 2008 would have required margins of well over 60% (60% is the average loss on the portfolio). No one prevented the officers controlling the worst Irish banks, if they felt constrained by the international accounting rules, from increasing their capital, selling their worst loans, reducing their dividends, or reducing their compensation. They could have disclosed to shareholders the enormous risk they were taking in making suicidal loans with virtually no ALLL. Their outside auditors could have demanded that they make such disclosures.)

Assume that Anglo was borrowing at 5%, had general and administrative expenses of 2%, and its ALLL was 0.3%. It made property loans at 8%. Its gross (before taxes) margin was 0.7%. At that margin, it could not survive even tiny levels of delinquencies and defaults, but it was making loans that would almost invariably default and suffer catastrophic losses.

Does Nyberg seriously think that if the ALLL had been 1.2% (v. 0.3%) the bank managers would have stopped making loans with 60% losses? The loans were insane for any honest bank – they were supremely rational for any accounting control fraud. Nyberg’s factual findings make an clear case for likely accounting control fraud. We can answer his confusion:

“Even with the benefit of hindsight, it is difficult to understand the precise reasons for a great number of the decisions made. However, it would appear that they generally were made more because of bad judgment than bad faith.” (Nyberg 2011: 11)

The facts that Nyberg found show that they were likely decisions of the most profound bad faith. His facts show that the people controlling Ireland’s worst banks chose to maximize their personal compensation at the expense of the bank, the Irish government, and the Irish people. If the reader frees himself from Nyberg’s unstated and crippling assumptions – fraud cannot drive financial crises and CEOs cannot be frauds (indeed they can’t even be bad chaps) – then the Irish bank managers’ specific behaviors that he describes are understandable.