By William K. Black

* Cross-posted with Benziga

Gary O’Callaghan, a former IMF economist has written about his distress over what he views as the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) destructive policies toward the periphery.

The ECB, EU, and the IMF are the troika that contributed to the periphery’s crises and have responded in such a destructive manner to the crises. O’Callaghan’s column urges the European finance ministers to focus on “three simple questions about the [troika’s] Irish, Greek and Portuguese” loan programs. My column focuses on the reasoning underlying his third question.

“Third, how important is it that the programs succeed? Obviously it is crucial. The success of the programs is key to the survival of the euro and should, therefore, take precedence over any other European agenda.”

O’Callaghan, unintentionally, has disclosed the core irrationality that underlies the euro. It is not “obvious” that “the survival of the euro” is critical, much less a goal of such transcendent importance that it should “take precedence over any other European agenda.” The euro is simply instrumental to some substantive purpose such as economic security, employment, or at least increased efficiency. The economic welfare of the people of the EU should be the EU’s transcendent economic goal.

O’Callaghan conflated “the survival of the euro” with the transcendent “European agenda” and the success of the EU loan programs to Ireland, Greece and Portugal with “the survival of the euro?” The EU existed for decades without the euro. A number of EU nations have chosen not to be members of the euro. The euro is not essential to an effective EU unless the EU wishes to become a true United States of Europe. That new sovereign nation would want a sovereign currency. The crisis had revealed that most French, Germans, and Finns do not view the Irish, Greeks, and Portuguese as fellow citizens of a United Europe. O’Callaghan calls on the EU to the discard the concept of European solidarity as “distracting rhetoric,” but he does not see that the euro has become one of the greatest threats to any “European agenda.”

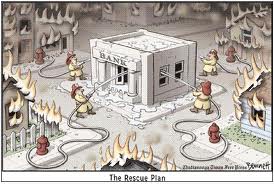

Why is O’Callaghan so disturbed about the EU and ECB’s lending program for Ireland? He is part of the IMF’s vast alumni corps and he’s horrified that the EU and the ECB are making the rookie mistakes common to novice loan sharks. The IMF knows how to bleed a nation – and it knows why the IMF bleeds nations. The IMF does not bail out poor nations. It bails out banks in rich nations that have made imprudent loans to poor nations. The IMF realizes that it is essential not to impose so much austerity that you kill rather than cripple the victim’s economy and harm the core’s banks. The ECB is dominated by theoclassical economists who have not yet learned this lesson. Their economic dogma is a variant on the old joke: the daily floggings will continue until morale improves around here. Bleeding is virtuous. If the victims aren’t screaming the ECB is not trying hard enough.

O’Callaghan writes primarily to convince the EU and the ECB to dial back the bleeding to the point where it is just sustainable. He urges them to “eliminate [] immediately” “punitive interest rates that undermine the chances of success.” O’Callaghan describes the ECB’s current loan terms as so bad that they are “preposterous.” “The rating agencies, the markets and most leading economists do not believe the plan is working.”

Sentient economists do not believe that imposing austerity during a severe recession is sensible. The CIA world book describes Ireland’s austerity program – prior to ECB demands for ever greater austerity – as “draconian” (and the CIA has special expertise with regard to the concept of “draconian”).

O’Callaghan key admission – the bailouts are essential to bail out the core’s banks

Why does O’Callaghan argue that it is essential that the ECB plan for the periphery succeed?

Because, it they are not implemented, the non-payment of debt – including bank debt – by the nations on the periphery would lead to severe banking crises and a return to recession in the core of eurozone.

That concession is refreshingly candid. The EU is not lending money to Ireland, Greece, and Portugal to help those nations’ citizens. The EU is lending those nations money because if they don’t those nations and their citizens and corporations will be unable to repay their debts to banks in the core. That will make public the fact that the core banks are actually insolvent. When the Germans and French realize that their banks are insolvent the result will be “severe banking crises and a return to recession in the core of the eurozone.” The core, not simply the periphery, will be in crisis. The ECB and the EU’s leadership would be happy to throw the periphery under the bus, but the EU core’s largest banks are chained to the periphery by their imprudent loans.

Destructive EU feedback loops: bad economics breed bad politics and worse economics

The leaders of the troika understand, but detest, the need to bail out the core’s insolvent banks by bailing out the periphery. They understand how much the EU public detests the bailouts and the resultant political cost in the core of supporting the bailouts. Their efforts to minimize that political cost lead them to demonize the periphery and support the ECB’s imposition of ever more draconian and self-defeating austerity programs on the periphery. The austerity programs are deepening the recessions in the periphery and creating far worse unemployment. The perverse economic policies create ever greater political instability in the periphery, massive resistance to austerity, and contempt for the core nation’s pretenses about European solidarity. As the perverse austerity programs cause the periphery’s recessions to deepen the likelihood that the likelihood of default increases, which further outrages the core’s population and threatens to unseat the core’s political leaders. Austerity locks the core and the periphery in a totentanz – a dance of death. The desire to save the euro and the core’s insolvent banks has become the greatest threat to the EU project.

Creating a sounder euro system

Even if the EU did need the euro, it does not need every EU member to be in the euro. If Ireland, Greece, and Portugal were to leave the euro and reintroduce sovereign currencies the number of EU nations using the euro would be greater than during the period the euro was introduced. The remaining members would have more uniform economies that would be closer to the economic concept we call an “optimum currency area” – making the new euro far less dangerous. That would make the euro and the EU’s member states stronger – both the core and the periphery.

The euro is ulcerous. The EU and ECB leadership do not understand this point. They see the obvious; the euro is “strong” relative to the other major currencies. Look underneath and the ulcers are weeping. The euro is so strong because the U.S., Japan, and China are deliberately and generally successfully weakening their currencies in order to increase exports. They all have sovereign currencies. They borrow at exceptionally low interest rates with U.S. and Japanese debt levels roughly equivalent to or in excess of Ireland, Greece, and Portugal.

The euro has become the tail that wags the EU dog, and it is wagging so destructively that it is throwing the periphery into the ditch. The EU response is to make the periphery dig itself ever deeper into that ditch and while showering the periphery with abuse. O’Callaghan’s assertion that it was “obvious” that the survival of the euro, not the well being of EU citizens, was the EU’s transcendent goal demonstrates the point. The euro is the problem – not the solution – for the periphery and the core.

It is essential that the nations of the EU periphery reclaim their sovereignty. Sovereign nations have a range of policy options to recover from recessions. They can lower interest rates, devalue their currencies, and increase public spending to offset lost demand in the private sector. Recessions cause real, severe economic and social losses. Unemployment is a pure deadweight loss. In a serious recession in a nation such as the U.S., the losses are measured in the trillions of dollars. Speeding the recovery from recession, ending unemployment, and avoiding hyper-inflation should be a sovereign nation’s transcendent economic goals at this time.

Because they lack sovereign currencies Ireland, Greece, and Portugal cannot effectively use any of these three means of fulfilling a sovereign nation’s economic functions. They cannot devalue. They cannot set monetary policy – they can’t even influence it. They can run small deficits. Small deficits do not come close to replacing the severe loss of private sector demand that occurs in serious recessions, so the EU “Growth and Stability Pact” is a double oxymoron. It limits growth, causes economic instability by leading to widespread unemployment, and causes political instability. It hamstrings the one thing we know reliably works to limit recessions – automatic stabilizers – by allowing them to only partially stabilize. The EU, as a matter of policy, provides far less effective automatic stabilizers than does the U.S. – in the name of producing “stability.” Neoclassical ECB economists, the designers and implementers of the euro and ECB, studiously ignore the significant insanity of this policy.

A functional sovereign nation addresses its home grown problems rather than ignoring them or blaming them on other nations. The ongoing crisis has shown that accounting control fraud in nations like the U.S., Ireland, Iceland, and Spain can cause the private sector to make trillions of dollars in destructive investments – sufficient to create massive bubbles and the Great Recession. The entities that are supposed to be best at providing “private market discipline” – the banks – rendered themselves insolvent by funding these bubbles instead of preventing them. These wasteful private sector investments should be a sovereign nation’s priority during the recovery from the Great Recession. But the private sector’s staggering destruction of wealth should not blind a sovereign nation to the problems of its public sector – crippling problems in Greece and severe in Iceland, Spain, and Ireland. The periphery needs to work in parallel on the interrelated crises of its private and public sectors.