By Glenn Stehle

Analyzing the nexus of war, economics, and society is a fascinating undertaking. War is the deployment of the state’s instruments of violence — the military and the police. So instead of the nexus of war, economics, and society, we could just as easily speak of the nexus of state violence, economics and society. And since Alt chose to make his article a morality tale, I would like to continue in that vein.

The two moral prerogatives which Alt articulates are 1) utilitarianism and 2) equality. We see this, for instance, when he notes that

At the finish line, however—VJ day, September 2, 1945—the U.S. had become the most powerful, efficient, and equitable economic power the world had ever seen.

However, I would argue that the marshalling of monetary power which Alt describes is normatively neutral, and that this sort of monetary policy can work just as easily for evil as it can for good. I am reminded of these comments by Steve Keen:

The rise of Hitler came about because Hitler, when he came to power, Germany had a massive level of unemployment, and was largely due to the American banks refusing to roll over the debt German industry owed it and causing a huge financial crisis in Germany. And then when Hitler came to power, he was told to balance the budget, and he basically told his economic minister where to go, and he locked him out of the room, ran huge deficits, built the welfare payment system, and built the industry for rearming, and basically Germany went from 25% unemployment to full employment. And that’s why people in Germany regarded Hitler as a God. So he got his legitimacy out of taking a contrarian approach to conventional economics to get out of the depression and succeeding. And that played a huge role in his rise and of course led to the second world war as well.

Which brings us to an intriguing question: Did the US’s very different moral prerogatives advantage the US in the war effort by causing greater utility?

Peter Turchin, in War and Peace in War, states that

The critical assumption in my argument is that cooperation provides the basis for imperial power. This assumption is at odds with the fundamental postulates of the dominant theories in social and biological sciences: the rational choice in economics and the selfish gene in evolutionary biology.

Turchin further argues that “the corrosive effect that glaring inequality has on the willingness of people to cooperate” destroys “the capacity of societies for collective action.”

The US was already a fairly equitable society at the time it entered WWII. The money-culture ethics and money worship of the Roaring Twenties had already been waylaid by the Great Depression, as Frederick Lewis Allen explains in Since Yesterday:

The times produced new creeds, new devotions.

But these were secular.

Their common denominator was social-mindedness; by which I mean that they were movements toward economic or social salvation – whether conceived in terms of prosperity or of justice or of mercy – not so much for individuals as such but for groups of people or for the whole nation, and also that they sought this salvation through organized action.

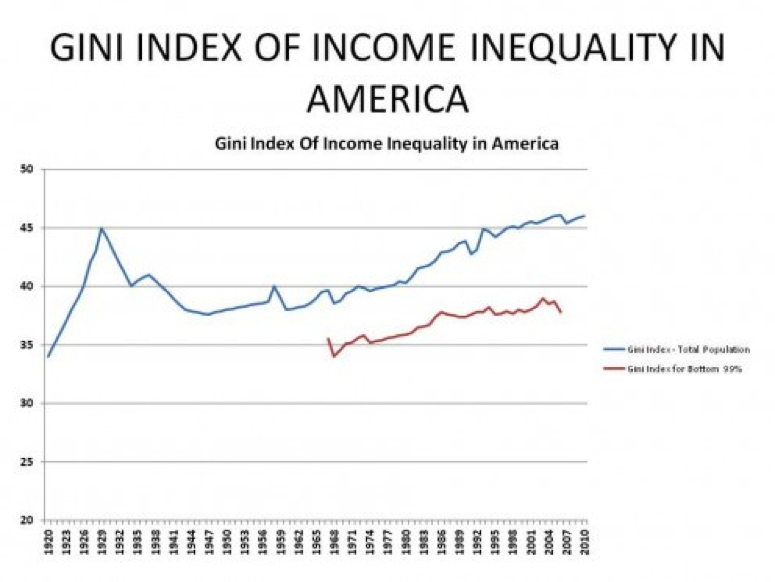

The great economic inequality that arose during the Roaring Twenties had also already been ameliorated by the Great Depression. Here is a graph of the Gini Index of Income Inequality in America for the period 1920 to 2010:

And under the wise guidance of President Roosevelt, the nation’s Jim Crow racial order also came under assault, as David Montejano explains in Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836 to 1986:

Social conflict and national crises provided the necessary impulse for the decline of old race arrangements. World War II, in particular, initiated dramatic changes on the domestic front. The need for soldiers and workers, and for positive international relations with Latin America, meant that the counterproductive and embarrassing customs of Jim Crow had to be shelved, at least for the duration of the emergency. In more lasting terms, the war created a generation of Mexican American veterans prepared to press for their rights and privileges. The cracks in the segregated order proved to be irreparable.

WWII profoundly reshaped American society. In the outstanding PBS special, A Class Apart, we see how these changes affected, for instance, Mexican Americans:

Benny Martínez: They were always referring to us as “dirty Mexicans.” They called us “pepper belly.” They called us “greasers.” They called us “wet back.” They made us feel ashamed to be a Mexican American.

Ignacio García: And as long as Mexican Americans believed that they couldn’t do anything about that, then they in a sense reinforce the system, the social stratification that occurred in their lives.

Narrator: Then came World War Two. Three hundred thousand Mexican Americans served their country. They suffered casualties and earned honors disproportionate to their numbers. They returned home with dramatically raised expectations, believing they had earned the right to first class citizenship.

Dr Ramiro Casso: We went to fight to give people liberty and to give them their civil rights, and then we come back home and we find that it is the same way as we left it!

Carlos Guerra: A great many people, came home expecting that they had won their full citizenship rights. When they come home and they’re decorated war heroes and they’re turned away from restaurants or told to go to the balconies of theaters, it created a building resentment. When their kids were not allowed to go to the good schools, it created a great deal of resentment.

Narrator: The treatment of Private Felix Longoria, a war hero killed in the Philippines, became a flashpoint. When his body was returned to his hometown of Three Rivers, Texas, in early 1949, the town’s only funeral parlor refused to hold a memorial service – because, they told Longoria’s widow, “the whites wouldn’t like it.”

Dr Ramiro Casso: This guy gave his life so that we could have the same rights and privileges that are available to everybody, and he couldn’t be buried with the whites because he was brown? What the hell?

Ignacio García: And it it really hits a nerve in the nation in particular with many veteran groups who say how can they not allow him to be buried.

Narrator: For Mexican Americans, the Longoria incident came at a crucial time. Since the twenties, civic organizations such as LULAC – the League of United Latin American Citizens – had begun pushing for civil rights, with some success. Now, emboldened by their war experience and growing political clout, Mexican American activists pressed demands for broader change. After an intense public campaign, Felix Longoria was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Ian Haney-López: And it’s this generation who fought in World War Two who begin to demand civil rights for Mexican Americans. They form important social organizations like the G.I. Forum. These organizations are committed to fighting for equality for Mexican Americans as well as to fighting for pride in Mexican origins.

The situation in Germany could not have been more different. Informed as they were by eugenics and social Darwinism, the Nazis created a dog-eat-dog society in which social and racial ordering were carried to the extreme. This not only resulted in a massive brain drain as scientists, intellectuals, writers, and artists either fled or were forced to leave Germany, but it seems to have greatly diminished the capacity for collective action, as this example illustrates:

Beyond the tangible reasons that the German effort never succeeded, the personalities of the German scientists inhibited their efforts. A simple example of this is the fact that in the first years of the war, when everyone in Germany believed that the war would be over by 1942, no scientist seriously considered the idea of developing an atomic weapon. Such a weapon would take years to develop and the war would be over before then. However, a much more important example is the conflicting personalities of the scientists themselves. Heisenberg later described the situation as each scientist being more concerned with increasing their own importance and funding then with successfully creating a self-sustained atomic reaction. What this meant is that German scientists often did not work together. At Farm Hall, Horst Korsching remarked, “[The atomic bomb] shows at any rate that the Americans are capable of real cooperation on a tremendous scale. That would have been impossible in Germany. Each one said that the other was unimportant” (Frank 75-76). Just one instance of this conflict occurred between Gerlach and Abraham Esau when both wanted to control the use of heavy water. The end of this conflict saw Gerlach in control of all atomic research and Esau refusing to work with him. This kind of lack of cooperation further damaged the German effort.

This example seems to belie the Utopian dream of neoliberals and neoconservatives, which is that science and technology can be used to perfect the implements of state violence to the point where cooperation is no longer needed.

Speaking of war, John J. Mearsheimer speaks of the abiding faith of the neoconservatives in science and technology to revolutionize the conduct of war. In their future ideal world, massive mobilizations, which require widespread citizen cooperation, are no longer needed for the war effort, only better implements of violence:

The neo-conservatives’ faith in the efficacy of bandwagoning was based in good part on their faith in the so-called revolution in military affairs (RMA). In particular, they believed that the United States could rely on stealth technology, air-delivered precision-guided weapons, and small but highly mobile ground forces to win quick and decisive victories. They believed that the RMA gave the Bush administration a nimble military instrument which, to put it in Muhammad Ali’s terminology, could “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.”

The American military, in their view, would swoop down out of the sky, finish off a regime, pull back and reload the shotgun for the next target. There might be a need for US ground troops in some cases, but that force would be small in number. The Bush doctrine did not call for a large army. Indeed, heavy reliance on a big army was antithetical to the strategy, because it would rob the military of the nimbleness and flexibility essential to make the strategy work.

This bias against big battalions explains why deputy secretary of defense Paul Wolfowitz (a prominent neo-conservative) and secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld dismissed out of hand (the then US army chief of staff) General Eric Shinsheki’s comment that the United States would need “several hundred thousand troops” to occupy Iraq. Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz understood that if the American military had to deploy huge numbers of troops in Iraq after Saddam was toppled, it would be pinned down, unable to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. A large-scale occupation of Iraq would undermine the Bush administration’s plan to rely on the RMA to win quick and decisive victories.

The quasi-religious faith that large mobilizations are no longer needed may help to explain why the neocons are so indifferent to public opinion, as we currently see with the Syrian escalation. If their theory is correct, after all, they really don’t need wide-spread public cooperation and participation — that is to put large numbers of boots on the ground — to fight and win wars.

But the neocon/neoliberal faith in the perfectibility of the state’s implements of violence through science and technology seems to cast an inward gaze too. In “On Violence,” Hannah Arendt notes that:

Even the tyrant, the One who rules against all, needs helpers in the business of violence, though their number may be rather restricted. However, the strength of opinion, that is, the power of the government, depends on numbers; it is “in proportion to the number which it is associated,” and tyranny, as Montesquieu discovered, is therefore the most violent and least powerful of forms of government. Indeed one of the most obvious distinctions between power and violence is that power always stands in need of numbers, whereas violence up to a point can manage without them because it relies on implements…

The extreme form of power is All against One, the extreme form of violence is One against All.

[….]

No government exclusively based on the means of violence has ever existed. Even the totalitarian ruler, whose chief instrument of rule is torture, needs a power basis – the secret police and its net of informers. Only the development of robot soldiers, which, as previously mentioned, would eliminate the human factor completely and, conceivably, permit one man with a push button to destroy whomever he pleased, could change this fundamental ascendancy of power over violence. Even the most despotic domination we know of, the rule of master over slaves, who always outnumbered him, did not rest on superior means of coercion as such, but on a superior organization of power – that is, on the organized solidarity of the masters. Single men without others to support them never have enough power to use violence successfully.

But what if the implements of state violence, as well as the capability to monitor social activity, can be perfected to such a degree that the need of others to support them is eliminated, or at least reduced to a very small band of loyal followers? Then the need for cooperation becomes all but nil.

If this neoliberal Utopia could be brought about, then mass cooperation would no longer be needed for either the conduct of military activities or for domestic social control. In such a world, the political and economic equality needed to elicit cooperation would no longer be needed. Utility would also undoubtedly suffer. But if domination and control are the only imperatives, then equality and utility cease to be moral prerogatives.

Author’s Bio:

Glenn was born in 1952 in Midland, Texas to a working class family where his father was a carpenter and mother a housekeeper. He received his Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering from University of Texas at El Paso in 1974 then worked in the Oil and Gas industry for Cities Service Oil Company followed by Union Texas Petroleum. He later became an independent consultant, specializing in drilling, completion and production operations as well as putting together oil and gas drilling prospects. In 1989 he founded a small telecom company, Call West Communications, with a partner and then in 2000 sold out and retired. After retiring he moved to Queretaro, Mexico where he spends his time reading, traveling and collecting Latin American art, mostly from the colonial period. He spent all but the first few years of his working career as a small business person.

18 responses to “A Response to J.D. Alt: Mobilization and Money”