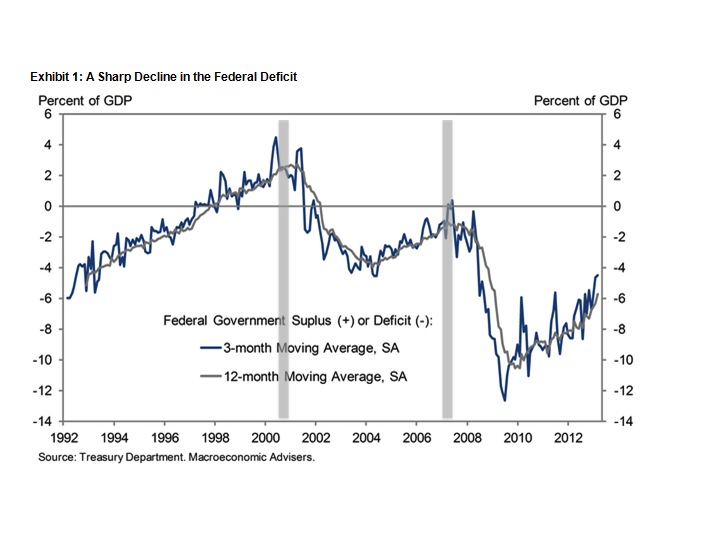

Neil Irwin at Wonkblog has a new post up: The Deficit is Falling Fast. Can Washington Accept Victory?

He quotes John Makin of the American Enterprise Institute, who says, approvingly, that the U.S. has probably imposed enough austerity “for now.” Then he shows us the evidence.

Irwin makes the obvious point that deficits tend to come down during the recovery phase of the cycle:

The economy is gradually healing, leading to higher tax revenue and reducing social welfare spending.

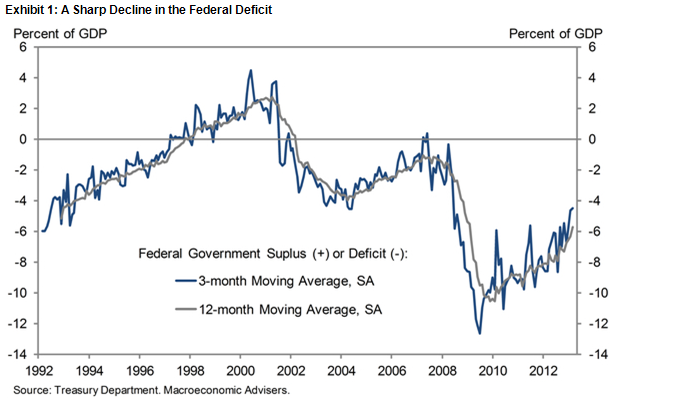

What he doesn’t show you is this:

It’s the same graph, but with recessions (grey bars) added. So what does it show? Basically, that the economy tends to go into recession whenever fiscal policy becomes too tight — a point made routinely by contributors to this blog. Unfortunately, it’s not something Irwin points out. Instead, he quotes Jan Hatzius (Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs), who says he expects the federal deficit to continue its downward trend, falling from its current level (about 4.5 percent of GDP) to 3 percent or less in FY2015.

It’s the same graph, but with recessions (grey bars) added. So what does it show? Basically, that the economy tends to go into recession whenever fiscal policy becomes too tight — a point made routinely by contributors to this blog. Unfortunately, it’s not something Irwin points out. Instead, he quotes Jan Hatzius (Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs), who says he expects the federal deficit to continue its downward trend, falling from its current level (about 4.5 percent of GDP) to 3 percent or less in FY2015.

Instead of raising a red flag about the consequences of letting the deficit get too small, Irwin offers this as prima facie good news. The basic argument being that we will have reduced the size of the deficit enough to keep us out of trouble — for the time being — so we can pause for a moment while we put together a plan to address our really pressing problem: unemployment the long-term deficit.

The lesson out of all this for Congress should be this: Focus on the long-term, not the short-term. The falling deficits of the next few years don’t solve the bigger longer-term problems the United States faces, on reining in rapidly rising health care costs and an unwieldy and frequently unfair tax code.

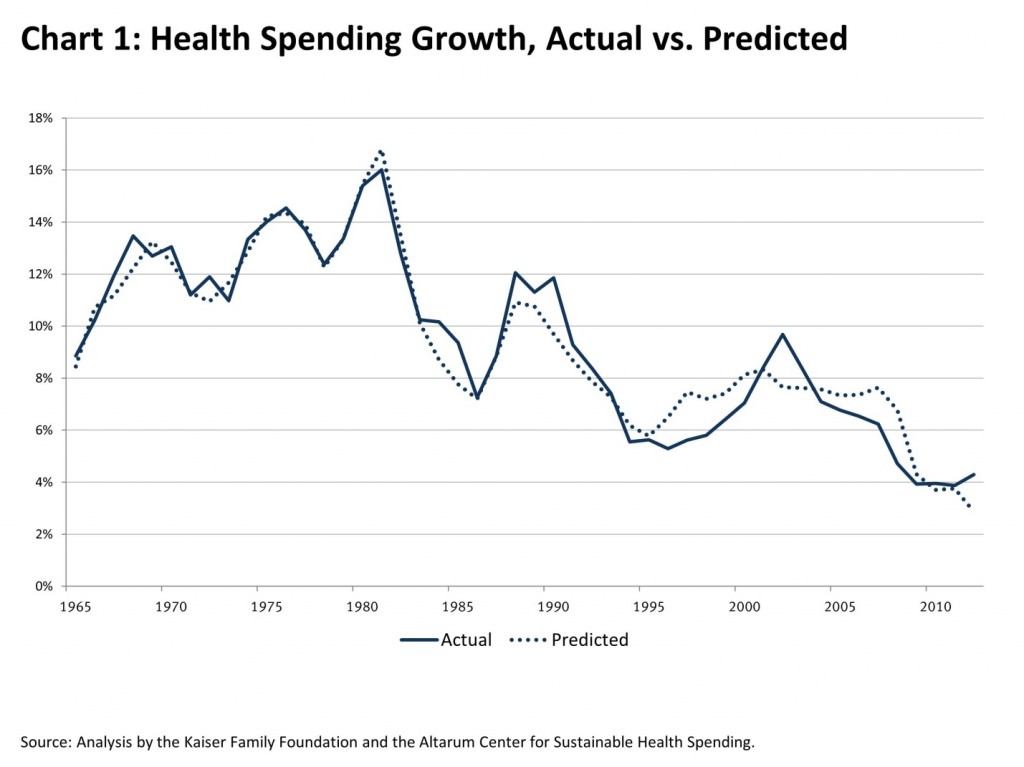

Alright, I can’t argue with the point about the tax code; it is unwieldy and frequently unfair, but let’s stop and examine Irwin’s other claim — the notion that we need to rein in rapidly rising health care costs because they are the drivers of the long-term fiscal woes.

What? Wait a minute. Health care costs are already being “reined in,” as Irwin’s Wonkblog co-contributor Sarah Kliff has shown. Health care costs have been growing at their slowest rate in decades. (It’s ironic that Irwin’s post is about how the deficit is actually falling, yet he fails to point out that something similar is happening with health care costs.)

And this is an important dragon to slay, because runaway health care costs are widely considered (by majorities in both parties) to be the primary driver of our long-term debt and deficit woes. Rather than slay it, Irwin feeds the beast.

Next time, he could reference this important analysis from two staffers at the Federal Reserve. It does to the CBO’s forecast of rising health care costs (and subsequently long-term debt and deficits) what Herndon, Ash and Pollin recently did to Reinhart & Rogoff’s “tipping point” predictions.

Even better, Irwin could go back to what Hatzius said here and ask him whether he thinks Goldman’s 3 percent deficit forecast is: (a) desirable or (b) sustainable. Specifically, he should ask Hatzius to explain what it would mean for the domestic private sector in a world in which the U.S. is running a current account deficit that exceeds 3 percent of GDP. (I’ve already traced out the implications here.)

The fundamental problems with so much of what’s written about debt and deficits are twofold: (1) Almost no one distinguishes those who are merely users of the currency from those who are currency issuers. It’s a huge oversight, and it leads to grave errors when predicting things like sustainability (or “tipping points”); (2) Almost no thinks about the government’s deficit in the proper (balance sheet) context. We are connected, domestically and globally, by our balance sheets. Outflows from one sector of the economy show up as inflows elsewhere, and government deficits are an important source of corporate profits.

It’s time more people stopped to think about what this necessarily implies when the government tightens its belt.

Pingback: Stephanie Kelton: Making The Case Against Austerity – The Doctor News

Pingback: Naked Capitalism on Austerity | Seniors for a Democratic Society

Pingback: "National debt” should be renamed “national savings”. | The Jefferson Tree