Knock-Knock.

Who’s there?

Money.

Anyone who writes about money (or for that matter debt or finance) knows what I’m about to say. Money scares the bejesus out of people.

Paul Krugman wrote about this in a recent post, entitled Monetary Rage, where he described the emotionally-charged reactions he gets from readers when he ventures into the dark underworld of money. As a young graduate student at MIT, Krugman was reportedly urged to avoid the money question at all costs (see here at 2:13), lest he be branded one of the unserious types. My colleague Randy Wray tells a story about the reaction he got from Robert Heilbroner when he asked Heilbroner to review his book Understanding Modern Money.

Let me go back to 1997 when I was finishing up my book titled Understanding Modern Money and I sent the manuscript to Robert Heilbroner to see if he’d write a blurb for the jacket. He called me immediately to tell me he could not do it.

As nicely as he could, he said (in the most soothing voice), “Your book is about money—the most terrifying topic there is. And this book is going to scare the hell out of everybody.”

I had a similar experience in a graduate macroeconomics class at Cambridge University. Willem Buiter was busy lecturing on IS-LM theory, when I raised my hand and asked something about endogenous money (a question I’ll admit was designed to challenge the underlying assumptions (loanable funds) in his model). I’ll never forget his response. He said:

If you are the type of person who thinks money is important, you’re probably the same type of person who would enjoy sitting in your basement and beating yourself with a rubber hose.

I obviously touched a nerve. The same kind of nerve Krugman occasionally touches and Heilbroner knew Randy would touch. Just what is it about money that tends to evoke such a visceral reaction in people?

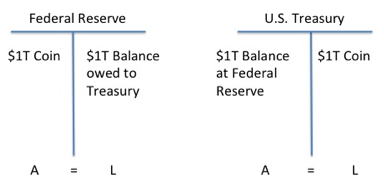

According to Krugman, it’s part political and part emotional. For more insight, we could ask Business Insider’s Joe Weisenthal, who has become the target of an intense campaign to stop the Secretary of the U.S. Treasury from striking a $1 trillion coin and depositing into its account at the Federal Reserve. Joe simply wanted to point out that there is an alternative to defaulting on the public debt that does not involve the 14th Amendment or the Supreme Court. If he wanted to, Timothy Geithner could exercise his legal authority to do this:

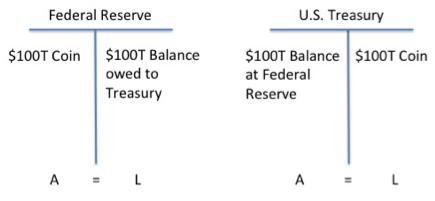

Or this:

A lot of people are hung up on the face value of the coin. Some want it smaller. (Perhaps they suffer from meganumaphobia.) Others want it much bigger. And many really, really, really don’t want it at all, even if it means enduring the catastrophic effects of a voluntary default on our nation’s debt.

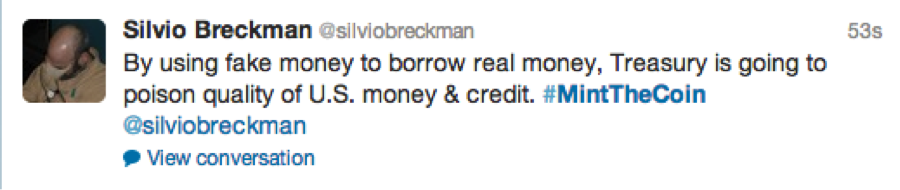

Krugman discusses this in his most recent post, Rage Against the Coin. Some say it would sink the dollar. Others (hilariously) say it would sink a ship!

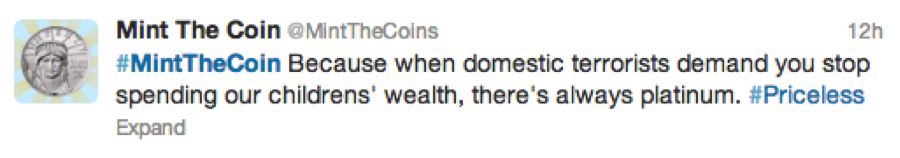

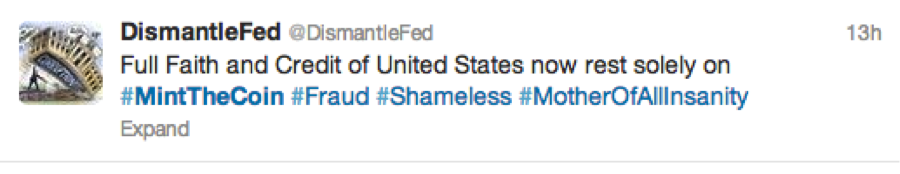

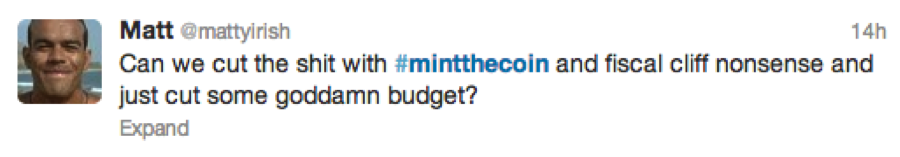

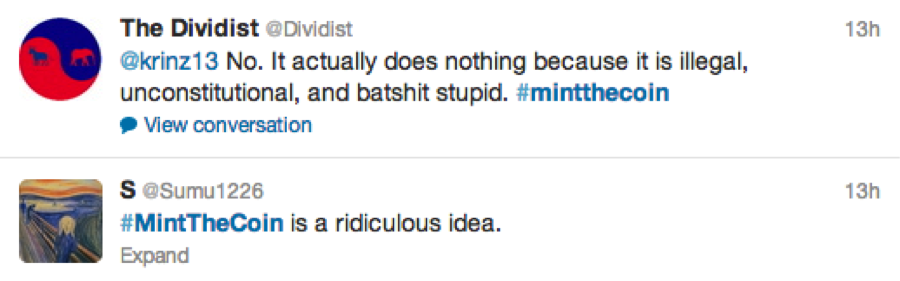

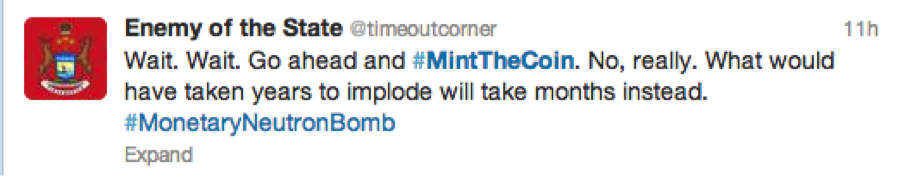

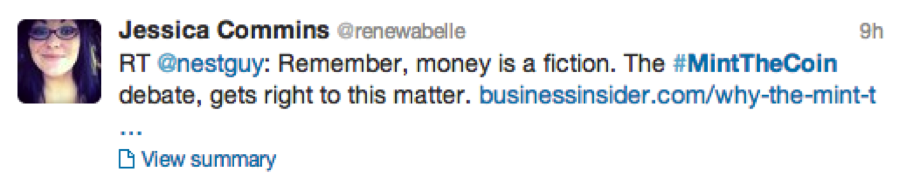

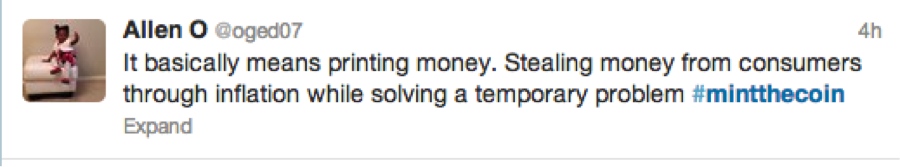

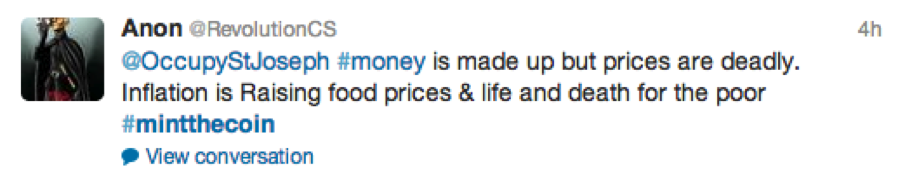

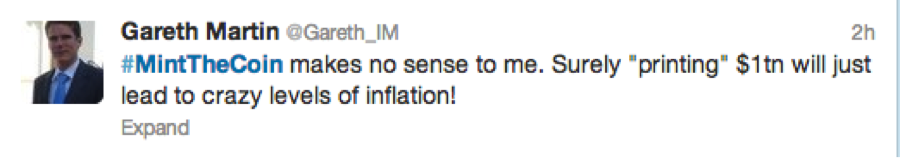

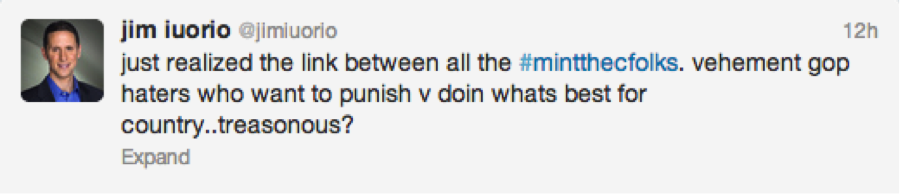

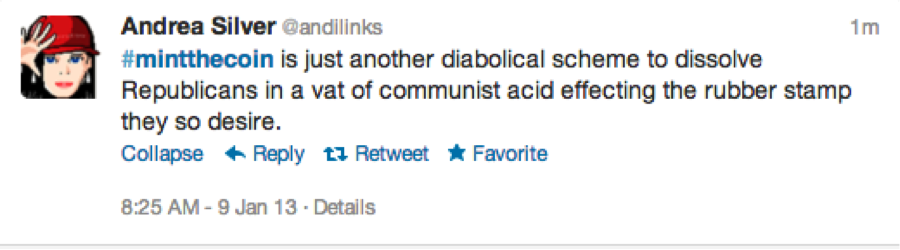

The best way to track the rage is by following the hash tag #MintTheCoin on Twitter. It offers great insight into the nature of the fear that so many people have about money, debt and finance.

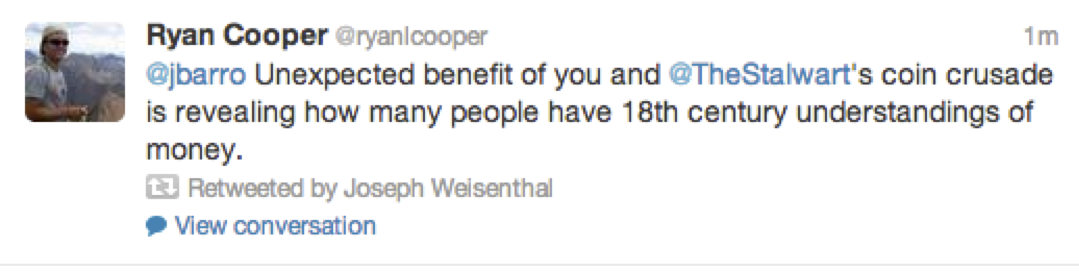

In spite of the rage the #MintTheCoin movement reveals, I think Ryan Cooper has it right.

Pingback: Platinozko txanpona: bilioi dolarrekoa | Heterodoxia, ekonomiaz haratago

Pingback: Our Leaders Are Mistaking the Modern Money System for a Fistful of Dollars - Part 1 - New Economic Perspectives