By Michael Hoexter

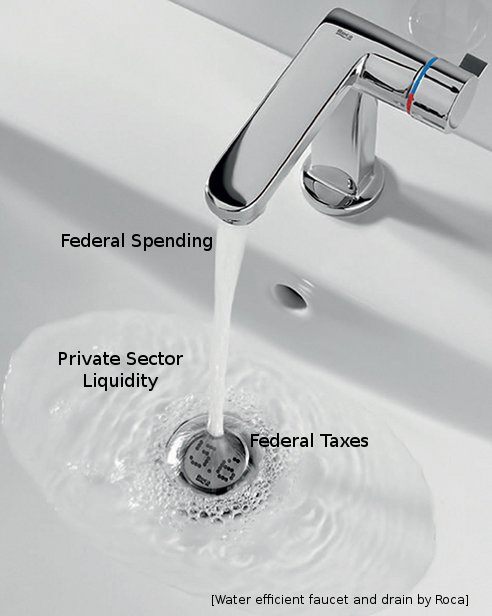

An Adjustable Liquidity Source and Liquidity Sink

While it may seem obvious and a tautology to treat money as a “liquidity source”, sometimes, especially in an area of life where there are many unexamined assumptions, it makes sense to rehearse the obvious. “High-powered” state-issued money is treated within accounting as an individual’s or a businesses “most liquid” asset but anything that functions as money confers “liquidity” on any individual who possesses that instrument or thing. Liquidity means that that object or instrument can be readily traded for wished-for goods and services. This liquidity can extend to “money-objects” other than state issued currency but the latter is in most contexts the most liquid money technology that we have.

The public monopoly of the currency provides households and businesses with a valuable public service, a more or less trusted universal exchange medium that enables transactions to occur easily and with a shared measure of value. However the currency does not simply exist outside of or as an “add on” to government. Government creates the currency and injects it into the economy by spending the currency into the private sector. In an era of electronic currencies and transactions, the creation and spending of the currency are simultaneous.

Modern fiat currencies are a sophisticated and powerful monetary technology because they enable leaders/managers of the macroeconomy to inject liquidity into the economy where and when it is viewed as necessary while also fulfilling the public mission of government, however that is dictated by the political process of the nation. These spending (and taxing) powers associated with a fiat currency can also be misused especially if they are not yoked to both a democratic political process of some description as well as a technical macroeconomic accounting process that measures, reports and analyzes variables related to social and environmental welfare accurately. These variables include unemployment, inflation and, I would add, carbon intensity, carbon emissions and other measures of environmental sustainability. In sum, a fiat currency is an instrument of great economic power that is a fact of modern life but can also be used or abused, depending on institutional and political arrangements.

In a fiat currency system, the amounts of government spending and taxation are financially independent of each other and can only be linked together by a political but not a financial or economic constraint. The spending of a fiat currency-issuing government is not dependent upon taxes collected to fund government spending as monetary units are not tied to some external limiting measure of value, like gold bullion or another metal. These precious metals are and were of course as arbitrary a measure of value as any other; they were simply an agreed-upon convention that itself was self-referential. The political right, which in many matters related to overall social welfare tries to limit the role of government, expresses nostalgia for the gold standard because it wants to use the limiting factor of a metal standard to control government’s role as a macroeconomic manager. In a fiat system, the currency is simply created by the government spending and with that spending liquidity is created in a particular sector of the economy into which the government has spent the money. The implementation of a fiat currency does not necessarily lead to inflation but it will tend to “err” on the side of inflation as the gold standard “errs” on the side of deflation.

In both a fiat and a metal standard monetary system, taxation by the central monetary authority drains liquidity out of a sector or activity of the economy, buffering the potentially inflationary effect of the money injected into the economy by government spending. The central bank affiliated with government can also continue to indirectly control the amount of money in circulation by braking or accelerating the private banking system’s drive to lend money by raising or lowering the interest rates. The division however between monetary and fiscal policy does not make sense in a fiat currency system; both the targeting of interest rates via the operations of the central bank and of fiscal policy (spending and taxation) are all part of the monetary system.

In a fiat currency system, the government also does not need to “ask the permission of” bond markets to spend more than taxes collected or “borrow” the currency from a foreign power or the domestic or international private sector. The institutional arrangements that require, for instance, the US government to issue bonds in the amount of budget deficits, creates the appearance of either “asking permission” or “borrowing” from the private sector or the rest of the world are political arrangements that are in part relics of the gold standard era where a government would have to back its currency by finding gold reserves somewhere to “back” deficit spending. This is an atavism from the gold standard era that needs to be revisited in light of our understanding of modern fiat currencies as well as the inevitable fiat element of all historical currencies. The source of the US dollar is the US government, not, for instance, the Chinese government.

To avoid excessive inflation or currency devaluation, the monetarily sovereign government also functions as a liquidity “sink” as well as a liquidity source, tamping down economic activity in a focal or more generalized way. The government can, for instance, impose higher taxes on the wealthy or on certain activities that are deemed socially harmful like financial trading or fossil fuel use. Higher taxes on the wealthy may blunt income inequality but do not solve the problem of the continual draining of liquidity from middle and lower socioeconomic strata, the people who are compelled to spend more of their money because of lower incomes. Therefore, as has resulted from the historical development of the welfare state, much deficit spending is in various social support programs like healthcare, education, unemployment insurance, and old age pensions which helps maintain effective demand for real goods and services among the middle and working classes.

Despite the inflationary “bias” of fiat currency, government has some ability to anticipate as well as track inflation and if there are inflationary pressures on the economy, the government can impose taxes which drain liquidity from the economy in a systematic way. Also monetary policy, the setting of interest rates, can dampen the contribution of private credit creation to inflation, which is more typically categorized as a inflation-fighting measure in current mainstream economics.

In summary, the reason that fiat currencies exist and are superior to currencies tied to a commodity like gold or to the value of other currencies, is that they are adjustable liquidity sources and sinks. By increasing spending above the amount of taxation (so-called “deficit spending”, which I have proposed should be named government’s “net contribution”), the managers of the macroeconomy in government, spending and taxation authorities like the US Congress, the President and the Treasury can compensate for the “natural” long-term draining of liquidity from the economy within capitalism by the tendency towards concentration of wealth. A fiat currency where deficit spending is allowed to occur thus enables growth to occur, as a fixed stock of money throughout the entire economy would stagnate or shrink the economy. Additionally using the tool of the fiat currency, the leaders of the macroeconomy can compensate for trade imbalances that will leave countries with trade deficits drained of monetary resources relative to their trading partners by injecting more liquidity into the economies of net importers than their governments remove via taxation. Otherwise trade imbalances would eventually shrink or collapse the economies of both net importers and eventually net exporting nations.

Of course, the government also spends to fulfill a broader public purpose beyond maintaining the liquidity of the economy. Spending on vital services that can only be supplied by government may take precedence in times of crisis and also during some periods of history create inflationary pressures which must be countered for instance by price controls, such as often happens in wartime.

The “Conservative” Perspective of the Householder or Business Owner on Money

The notions of injecting or draining liquidity from the economy, one independently of the other, are very far from the perspective on money that a householder or a business owner generally have. Businesses and householders are “budgetarily constrained” meaning that they must operate with the notion that there exists in practical terms only a fixed amount of money in their accounts now and new money of necessity must be acquired from outside themselves or their organization: they must either borrow it or receive it in payment. While it is not critical for a currency issuing government to save its own money in a bank account from one accounting period to the next, for a household or business this activity is, besides sustaining oneself and one’s family, the point of economic activity in a capitalist economic system.

It may help then for households and businesses to then view money as if it is, in terms of physics and not politics, a conservative system, as a closed system with a limited number of items in it, which are shuffled or rearranged between a set of economic actors very much like themselves. Within the bounds of the system, matter and energy are conserved in the physical version of a conservative system and in the economic version, money is conserved, neither growing nor decreasing in amount. Households and businesses MUST “economize”, i.e. maintain their expenses below their income, in order to survive and/or to save. Conventional accounting, which is also used and sometimes misapplied for the accounting of fiat currency-issuing governments as well, operates according to this principle which recognizes only that has been taken in and what has been spent and creates from that a balance sheet. The goal of saving money and of managing a limited budget are paramount concerns for householders and businesses, all of which are predicated on the constancy and finitude of the store of money available. From the business or household perspective, the notion of money being created and destroyed in large amounts to achieve macroeconomic goals is an entirely different and, for many, an alien perspective.

The “micro”, on the ground, view of money is therefore different from that of the “macro” currency-issuing government but is no less real and it provides the individual householder or business owner with some sensible rules of thumb. Their ideas and attitudes about money are however not very helpful guides for macroeconomic managers in government to follow.

Austerity as Denial of Macroeconomic and Monetary Reality

Despite these clear differences in perspective and the differing truths that they reveal, there have always remained factions within economics and in the business community that could not accept that somehow the prescriptions for individual economic success and overall social welfare would differ. They insisted that saving was always and for every actor a virtue and that the experience of businesspeople was as applicable to government as it is to running a business. The so-called “Austrian” school, among which Keynes’s chief early opponent Friedrich von Hayek can be counted, insisted that market actors did not need the supervision of a government entity and that there were “natural” trends within markets and the pricing system which would stabilize the economy by themselves. Given a study of the history of the actual economy, the self-centered and stubborn naïveté of this view is exposed as laughable but unfortunately more widespread and influential than we would hope. Certain wealthy people, in particular, seem to feel that the route to their success is the route to the success of the entire society or, more likely, their success matters and is more important than the success of society as a whole. This is where the egocentricity of what might be called the hard-money view of government finance becomes a dangerous form of narcissistic entitlement, a malignant economic narcissism.

The austerity campaign has exploited the confusion and/or willful assertion by wealthy and powerful participants in the economy that the economic management of the economy as a whole and of individual businesses or households operates along similar principles. That neoclassical economics has no place within the structure of its main theory for money, let alone the mechanics of a fiat currency, has left an opening for austerity advocates to claim that governments should trim their deficit spending at exactly the wrong time and should attempt to “save” or accumulate money as would a household or business. The misapplication of business economics to the economics of national economies has already had harrowing effects everywhere it has been applied and there is no reason to believe that its application in the future will have any different results.

A critical element of modern macroeconomic management is realizing the potential of fiat currencies to inject liquidity into economies which are experiencing high unemployment, declining median wages, or where effective demand is undermined by large overhangs of private debt. The fiat currency’s independence of government spending from tax receipts enables managers of the macroeconomy in a downturn to up spending as much as needed to face any number of social and economic challenges facing the nation. Austerity advocates’ denial of the fiat reality of our currencies leads, as is currently the trend, to untold hardship and an utter failure to lead the economy out of its current socioeconomic and ecological morass.

Pingback: Why focusing on the foreign exchange rate won’t get us anywhere | Reality-based World View

Pingback: Our Leaders Are Mistaking the Modern Money System for a Fistful of Dollars – Part 2 | Real Economy Notes | Scoop.it