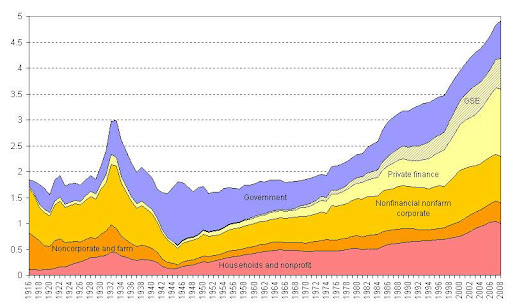

Answer: This news report reflects two related misunderstandings: first, that government “funds” its deficit by borrowing; second that a large deficit threatens government with insolvency. Let me first deal with those fallacies, then move on to what is happening in markets.

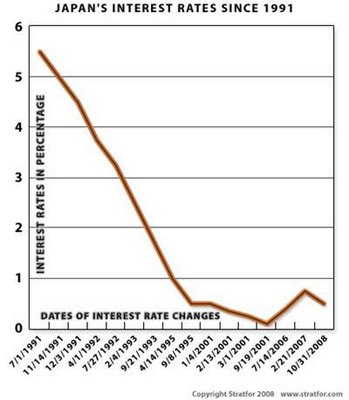

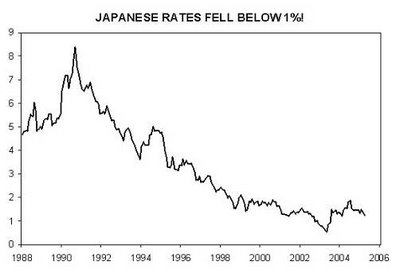

Government spends by crediting bank accounts (bank deposits go up, and their reserves are credited by the Fed). All else equal, this generates excess reserves that are offered in the overnight interbank lending market (fed funds in the US) putting downward pressure on overnight rates. Let me repeat that: government spending pushes interest rates down. When they fall below the target, the Fed sells bonds to drain the excess reserves—pushing the overnight rate back to the target. Continuous budget deficits lead to continuous open market sales, causing the NY Fed to call on the Treasury to soak up reserves through new issues of bonds. The purpose of bond sales by the Fed or Treasury is to substitute interest-earning bonds for undesired reserves—to allow the Fed to hit its interest rate target. (In the old days, these reserves earned no interest; Chairman Bernanke has changed that, effectively eliminating the difference between very short-term Treasuries and bank reserves. It also entirely eliminates the need to issue Treasuries—but that is a topic for another day.) We conclude: government deficits do not exert upward pressure on interest rates—quite the contrary, they put downward pressure that is relieved through bond sales.

On to the question of insolvency. Let me state the conclusion first: a sovereign government that issues its own floating rate currency can never become insolvent in its own currency. (While such a currency is often called “fiat”, that is somewhat misleading for reasons I won’t discuss here—I prefer the term “sovereign currency”.) The US Treasury can always make all payments as they come due—whether it is for spending on goods and services, for social spending, or to meet interest payments on its debt. While analogies to household budgets are often made, these are completely erroneous. I do not know any households that can issue Treasury coins or Federal Reserve Notes (I suppose some try occasionally, but that is dangerously illegal counterfeiting). To be sure, government does not really spend by direct issues of coined nickels. Rather, it spends by crediting bank accounts. It taxes by debiting them. When its credits to bank accounts exceeds its debits to them, we call that a budget deficit. The accounting and operating procedures adopted by the Treasury, the Fed, special deposit banks, and regular banks are complex, but they do not change the principle: government spending is accomplished by crediting bank accounts. Government spending can be too big (beyond full employment), it can misdirect resources, and it can be wasteful or undesirable, but it cannot lead to insolvency.

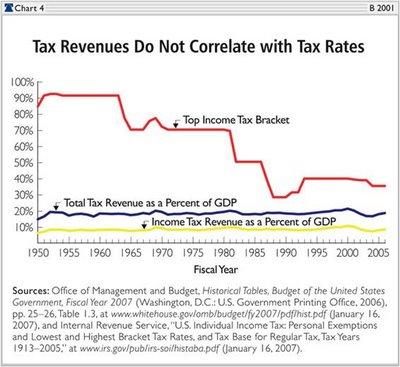

Constraining government spending by imposing budgets is certainly desirable. We want to know in advance what the government is planning to do, and we want to hold it accountable; a budget is one lever of control. At this point, it is impossible to know how much additional government spending will be required to get us out of this deep recession. Whether the Obama team finally settles on $850 billion worth of useful projects, or $1.5 trillion, voters have the right to expect that the spending is well-planned and that the projects are well-executed. But the budgets ought to be set with regard to results desired and competencies to execute plans—not out of some pre-conceived notion of what is “affordable”. Our federal government can afford anything that is for sale in terms of its own currency. The trick is to ensure that it spends enough to produce sustainable growth and other desired outcomes while at the same time ensuring that its spending does not have undesirable outcomes such as fueling inflation or taking away resources that could be put to better use by the private sector.

Why do stock markets and bond markets react the way they do, given that insolvency is out of the question? Sophisticated market players do recognize that government cannot go insolvent and that government will always make all interest payments as they come due. Markets are, however, concerned that all the government spending plus the Fed bail-outs (lending reserves and buying bad assets) will be inflationary. In the current environment, that is quite unlikely. Even if oil prices stabilize at a higher level, that will not compensate for all the deflationary pressures around the world as firms cut prices to maintain sales in the face of plummeting demand. Still, it is not really inflation that bond markets are worried about, but rather future Fed interest rate hikes. (Again, that will not happen in the near future, and might not happen for several years—but there is little doubt that the Fed will eventually raise rates when the economy finally recovers.) Rate hikes lead to capital losses on longer-maturity bonds (interest rates and bond prices always move in the opposite direction). The Treasury persists in issuing bonds with a range of maturities (although the maturity structure in recent years has shortened). This is evidence that the Treasury does not fully understand the purpose of bond sales (since bonds are simply an alternative to bank reserves, it makes most sense to offer only overnight bonds)—but, again, that is a topic for another day.

The Treasury is having some trouble selling the longer maturity bonds (so their price is low and their interest rate is high). China is probably playing a role in this because they are shunning longer maturity debt out of fear of capital losses; they have also shifted some of their portfolio to other currencies (partly to diversify so that they will not lose if the dollar depreciates, and perhaps to pressure US authorities to keep the dollar strong). The solution is that the Treasury should shift even more strongly to shorter maturities—something it will do even if it does not fully understand why it should: Treasury sees that short term interest rates are much lower, hence, will sell short term debt to reduce the “cost of funding the deficit”. If Treasury really understood what it was doing, it would simply offer overnight deposits at the Fed, paying the Fed’s target interest rate. Then it would not “need” to sell bonds at all, and we could stop worrying about government “borrowing from the Chinese”. If the Fed wanted to control interest rates of longer term debt, it can offer interest on deposits of different maturities—for example, it can offer an overnight rate, a 30 day rate, a 90 day rate, and so on, for deposits held at the Fed.