Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

February 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

William K. Black on the Charges Filled by the SEC against Goldman Sachs

Comments Off on William K. Black on the Charges Filled by the SEC against Goldman Sachs

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged William K. Black

GOLDMAN SACHS VAMPIRE SQUID GETS HANDCUFFED

L. Randall Wray

In a startling turn of events, the SEC announced a civil fraud lawsuit against Goldman Sachs. I use the word startling because a) the SEC has done virtually nothing in the way of enforcement for years, managing to sleep through every bubble and bust in recent memory, and b) Government Sachs has been presumed to be above the law since it took over Washington during the Clinton years. Of course, there is nothing startling about bad behavior at Goldman—that is its business model. The only thing that separates Goldman on that score from all other Wall Street financial institutions is its audacity to claim that it channels God as it screws its customers. But when the government is your handmaiden, why not be audacious?

The details of the SEC’s case will be familiar to anyone who knows about Magnetar. This hedge fund sought the very worst subprime mortgage backed securities (MBS) to package as collateralized debt obligations (CDO). The firm nearly single-handedly kept the subprime market afloat after investors started to worry about Liar and NINJA loans, since Magnetar was offering to take the very worst tranches—making it possible to sell the higher-rated tranches to other more skittish buyers. And Magnetar was quite good at identifying trash: According to an analysis commissioned by ProPublica, 96% of the CDO deals arranged by Magnetar were in default by the end of 2008 (versus “only” 68% of comparable CDOs). The CDOs were then sold-on to investors, who ultimately lost big time. Meanwhile, Magnetar used credit default swaps (CDS) to bet that the garbage CDOs they were selling would go bad. Actually, that is not a bet. If you can manage to put together deals that go bad 96% of the time, betting on bad is as close to a sure thing as a financial market will ever find. So, in reality, it was just pick pocketing customers—in other words, a looting.

Well, Magnetar was a hedge fund, and as they say, the clients of hedge funds are “big boys” who are supposed to be sophisticated and sufficiently rich that they can afford to lose. Goldman Sachs, by contrast, is a 140 year old firm that operates a revolving door to keep the US Treasury and the NY Fed well-stocked with its alumni. As Matt Taibi has argued, Goldman has been behind virtually every financial crisis the US has experienced since the Civil War. In John Kenneth Galbraith’s “The Great Crash”, a chapter that documents Goldman’s contributions to the Great Depression is titled “In Goldman We Trust”. As the instigator of crises, it has truly earned its reputation. And it has been publicly traded since 1999—an unusual hedge fund, indeed. Furthermore, Treasury Secretary Geithner handed it a bank charter to ensure it would have cheap access to funds during the financial crisis. This gave it added respectability and profitability—one of the chosen few anointed by government to speculate with Treasury funds. So, why did Goldman use its venerable reputation to loot its customers?

Before 1999, Goldman (like the other investment banks) was a partnership—run by future Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson. The trouble with that arrangement is that it is impossible to directly benefit from a run-up of the stock market. Sure, Goldman could earn fees by arranging initial public offerings for Pets-Dot-Com start-ups, and it could trade stocks for others or for its own account. This did offer the opportunity to exploit inside information, or to monkey around with the timing of trades, or to push the dogs onto clients. But in the euphoric irrational exuberance of the late 1990s that looked like chump change. How could Goldman’s management get a bigger share of the action?

Flashback to the 1929 stock market boom, when Goldman faced the same dilemma. Since the famous firms like Goldman Sachs were partnerships, they did not issue stock; hence they put together investment trusts that would purport to hold valuable equities in other firms (often in other affiliates, which sometimes held no stocks other than those in Wall Street trusts) and then sell shares in these trusts to a gullible public. Effectively, trusts were an early form of mutual fund, with the “mother” investment house investing a small amount of capital in their offspring, highly leveraged using other people’s money. Goldman and others would then whip up a speculative fever in shares, reaping capital gains through the magic of leverage. However, trust investments amounted to little more than pyramid schemes—there was very little in the way of real production or income associated with all this trading in paper. Indeed, the “real” economy was already long past its peak—there were no “fundamentals” to drive the Wall Street boom. It was just a Charles Ponzi-Bernie Madoff scam. Inevitably, Goldman’s gambit collapsed and a “debt deflation” began as everyone tried to sell out of their positions in stocks—causing prices to collapse. Spending on the “real economy” suffered and we were off to the Great Depression. Sound familiar?

So in 1999 Goldman and the other partnerships went public to enjoy the advantages of stock issue in a boom. Top management was rewarded with stocks—leading to the same pump-and-dump incentives that drove the 1929 boom. To be sure, traders like Robert Rubin (another Treasury secretary) had already come to dominate firms like Goldman. Traders necessarily take a short view—you are only as good as your last trade. More importantly, traders take a zero-sum view of deals: there will be a winner and a loser, with Goldman pocketing fees for bringing the two sides together. Better yet, Goldman would take one of the two sides—the winning side, of course–and pocket the fees and collect the winnings. You might wonder why anyone would voluntarily become Goldman’s client, knowing that the deal was ultimately zero-sum and that Goldman would have the winning hand? No doubt there were some clients with an outsized view of their own competence or luck; but most customers were wrongly swayed by Goldman’s reputation that was being exploited by hired management. The purpose of a good reputation is to exploit it. That is what my colleague, Bill Black, calls control fraud.

Note that before it went public, only 28% of Goldman’s revenues came from trading and investing activities. That is now about 80% of revenue. While many think of Goldman as a bank, it is really just a huge hedge fund, albeit a very special one that happens to hold a Timmy Geithner-granted bank charter—giving it access to the Fed’s discount window and to FDIC insurance. That, in turn, lets it borrow at near-zero interest rates. Indeed, in 2009 it spent only a little over $5 billion to borrow, versus $26 billion in interest expenses in 2008—a $21 billion subsidy thanks to Goldman’s understudy, Treasury Secretary Geithner. It was (until Friday) also widely believed to be “backstopped” by the government—under no circumstances would it be allowed to fail, nor would it be restrained or prosecuted—keeping its stock price up. That is now somewhat in doubt, causing prices to plummet. Of course, the FDIC subsidy is only a small part of the funding provided by government—we also need to include the $12.9 billion it got from the AIG bail-out, and a government guarantee of $30 billion of its debt. Oh, and Goldman’s new $2 billion headquarters in Manhattan? Financed by $1.65 billion of tax free Liberty Bonds (interest savings of $175 million) plus $66 million of employment and energy subsidies. And it helps to have your people run three successive administrations, of course.

Unprecedented and unprecedentedly useful if one needs to maintain reputation in order to run a control fraud.

In the particular case prosecuted by the SEC, Goldman created synthetic CDOs that placed bets on toxic waste MBSs. A synthetic CDO does not actually hold any mortgage securities—it is simply a pure bet on a bunch of MBSs. The purchaser is betting that those MBSs will not go bad, but there is an embedded CDS that allows the other side to bet that the MBSs will fall in value, in which case the CDS “insurance” pays off. Note that the underlying mortgages do not need to go into default or even fall into delinquency. To make sure that those who “short” the CDO (those holding the CDS) get paid sooner rather than later, all that is required is a downgrade by credit rating agencies. The trick, then, is to find a bunch of MBSs that appear to be over-rated and place a bet they will be downgraded. Synergies abound! The propensity of credit raters to give high ratings to junk assets is well-known, indeed assured by paying them to do so. Since the underlying junk is actually, well, junk, downgrades are also assured. Betting against the worst junk you can find is a good deal—if you can find a sucker to take the bet.

The theory behind shorting is that it lets you hedge risky assets in your portfolio, and it aids in price discovery. The first requires that you’ve actually got the asset you are shorting, the second relies on the now thoroughly discredited belief in the efficacy of markets. In truth, these markets are highly manipulated by insiders, subject to speculative fever, and mostly over-the-counter. That means that initial prices are set by sellers. Even in the case of MBSs—that actually have mortgages as collateral—buyers usually do not have access to essential data on the loans that will provide income flows. Once we get to tranches of MBSs, to CDOs, squared and cubed, and on to synthetic CDOs we have leveraged and layered those underlying mortgages to a degree that it is pure fantasy to believe that markets can efficiently price them. Indeed, that was the reason for credit ratings, monoline insurance, and credit default swaps. CDSs that allow bets on synthetics that are themselves bets on MBSs held by others serve no social purpose whatsoever—they are neither hedges nor price discovery mechanisms.

The most famous shorter of MBSs is John Paulson, who approached Goldman to see if the firm could create some toxic synthetic CDOs that he could bet against. Of course, that would require that Goldman could find chump clients willing to buy junk CDOs—a task for which Goldman was well-placed. According to the SEC, Goldman allowed Paulson to increase the probability of success by allowing him to suggest particularly trashy securities to include in the CDOs. Goldman arranged 25 such deals, named Abacus, totaling about $11 billion. Out of 500 CDOs analyzed by UBS, only two did worse than Goldman’s Abacus. Just how toxic were these CDOs? Only 5 months after creating one of these Abacus CDOs, the ratings of 84% of the underlying mortgages had been downgraded. By betting against them, Goldman and Paulson won—Paulson pocketed $1 billion on the Abacus deals; he made a total of $5.7 billion shorting mortgage-based instruments in a span of two years. This is not genius work—84% to 96% of CDOs that are designed to fail will fail.

Paulson has not been accused of fraud—while he is accused of helping to select the toxic waste, he has not been accused of misleading investors in the CDOs he bet against. Goldman, on the other hand, never told investors that the firm was creating these CDOs specifically to meet the demands of Paulson for an instrument to allow him to bet them. The truly surprising thing is that Goldman’s patsies actually met with Paulson as the deals were assembled—but Goldman never informed them that Paulson was the shorter of the CDOs they were buying! The contempt that Goldman shows for clients truly knows no bounds. Goldman’s defense so far amounts to little more than the argument that a) these were big boys; and b) Goldman also lost money on the deals because it held a lot of the Abacus CDOs. In other words, Goldman is not only dishonest, but it is also incompetent. If that is not exploitation of reputation by Goldman’s management, I do not know what would qualify.

By the way, remember the AIG bail-out, of which $12.9 billion was passed-through to Goldman? AIG provided the CDSs that allowed Goldman and Paulson to short Abacus CDOs. So AIG was also duped, as was Uncle Sam—although that “sting” required the help of the New York Fed’s Timmy Geithner. I would not take Goldman’s claim that it lost money on these deals too seriously. It must be remembered that when Hank Paulson ran Goldman, it was bullish on real estate; through 2006 it was accumulating MBSs and CDOs—including early Abacus CDOs. It then slowly dawned on Goldman that it was horribly exposed to toxic waste. At that point it started shorting the market, including the Abacus CDOs it held and was still creating. Thus, while it might be true that Goldman could not completely hedge its positions so that it got caught holding junk, that was not for lack of trying to push all risks onto its clients. The market crashed before Goldman found a sufficient supply of suckers to allow it to short everything it held. Even vampire squids get caught holding garbage.

Some have argued that the SEC’s case is weak. It needs to show not only that Goldman misled investors, but also that this was materially significant in creating their losses. Would they have forgone the deals if they had known that Paulson was shorting their asset? We do not know—the SEC will have to make the case. Besides, Goldman does this to all its clients—so the SEC will have to make the case that clients could have been misled, whilst knowing that Goldman screws all its clients. After all, Goldman hid Greece’s debt, then bet against the debt—another fairly certain bet since debt ratings would fall if the hidden debt was ever discovered. Goldman took on US states as clients (including California and New Jersey and 9 other states), earning fees for placing their debts, and then encouraged other clients to bet against state debt—using its knowledge of the precariousness of state finances to market the instruments that facilitated the shorts. Did Goldman do anything illegal? We do not yet know. Reprehensible? Yes. Normal business practice.

To be fair, Goldman is not alone—all of this appears to be normal business procedure. In early spring 2010 a court-appointed investigator issued his report on the failure of Lehman. Lehman engaged in a variety of “actionable” practices (potentially prosecutable as crimes). Interestingly, it hid debt using practices similar to those employed by Goldman to hide Greek debt. The investigator also showed how the prices by Lehman on its assets were set—and subject to rather arbitrary procedures that could result in widely varying values. But most importantly, the top management as well as Lehman’s accounting firm (Ernst&Young) signed off on what the investigator said was “materially misleading” accounting. That is a go-to-jail crime if proven. The question is why would a top accounting firm as well as Lehman’s CEO, Richard Fuld, risk prison in the post-Enron era (similar accounting fraud brought down Enron’s accounting firm, and resulted in Sarbanes-Oxley legislation that requires a company’s CEO to sign off on company accounts)? There are two answers. First, it is possible that fraud is so wide-spread that no accounting firm could retain top clients without agreeing to overlook it. Second, fraud may be so pervasive and enforcement and prosecution thought to be so lax that CEOs and accounting firms have no fear. I think that both answers are correct.

To determine whether Goldman and other firms engaged in fraud will require close examination of the books, internal documents, and emails. Perhaps the SEC has finally fired the first shot at the Wall Street firms that aided and abetted the creation of the conditions that led up to the financial collapse. More importantly, that first shot might have driven a bit of fear into the financial institutions that have been trying to carry-on with business as usual. And, finally, perhaps the SEC might induce the Obama administration to stand-up to Goldman.

It is probably not too early for Goldman management and alumni to begin packing bags for extended stays in our nation’s finest penitentiaries. More than 1000 top management at thrifts served real jail time in the aftermath of the Savings and Loan fiasco. This current scandal is many orders of magnitude greater—probably tens of thousands of managers and traders and government officials were involved in fraud. We may need dozens of new prisons to contain them.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration should immediately revoke Goldman’s bank charter. Even if the firm is completely cleared of illegal activities, it is not a bank. There is no justification for provision of deposit insurance for a firm that specializes in betting against its clients. Its business model is at best based on deception, if not outright fraud. It serves no useful purpose; it does not do God’s work. Government should also relieve itself of all Goldman alumni—no administration that is full of Goldman’s people can retain the trust of the American public. President Obama should start his house cleaning with the Treasury department. Yes, Rubin and his hired hand Summers and protégé Geithner (and his hired hand Mark Patterson, Goldman’s lobbyist who became chief of staff of the Treasury) and Hank Paulson must be banned from Washington; and Rattner (former NYTimes reporter who tried to bribe pensions funds when he worked for the Quadrangle Group—who served as Obama’s “car czar” and is now likely to face lawsuits), and Lewis Sachs (senior advisor to Treasury, who helped Tricadia to make bets identical to those made by Magnetar and Goldman), and Stephen Friedman (Goldman senior partner who served as chairman of the NYFed), and NY Fed president Dudley (former chief US economist at Goldman) must all be sent home. Actually, anyone who ever worked for a financial institution must be banned from Washington until we can reform and downsize and drive a stake through the heart of Wall Street’s vampires.

And why not use the powers of eminent domain to take back Goldman’s shiny new government-subsidized headquarters to serve as the offices for 6000 newly hired federal government white collar criminologists tasked with the mission to pursue Wall Street’s fraud from the Manhattan citadel of the mighty vampire squid? If Obama is serious about reform, that would be a first step.

What is Responsible Fiscal Policy?

I can’t fault the taxpayer for being upset with the deficit. I blame my profession, which has been spewing nonsense about government spending for decades. Economics is long-overdue for a renaissance. The deficit phobia, not the deficit itself, should be made public enemy #1. Taxpayers are decidedly working against their own interests when they demand that the government reduce or eliminate its deficit. Here is why:

Government deficits create non-government surpluses. It is a simple mathematical proposition; it is neither high theory, nor rocket science. If one sector spends more than it earns, another, by the rules of double-entry bookeeping, earns more than it spends. And so it is with the government—if it spends more than it collects in taxes, it runs a deficit, which is exactly equal to the surplus accumulated by the non-government sector. Deficits create income and profits for the private sector in excess of the taxes the private sector pays to the government. My fellow bloggers have explained this clearly many times before (e.g. here, here and here).

“My alternative proposal on trade with China”

By Warren Mosler*

We can have BOTH low priced imports AND good jobs for all Americans

Attorney General Richard Blumenthal has urged US Treasury Secretary Geithner to take legal action to force China to let its currency appreciate. As stated by Blumenthal: “By stifling its currency, China is stifling our economy and stealing our jobs. Connecticut manufacturers have bled business and jobs over recent years because of China’s unconscionable currency manipulation and unfair market practices.”

The Attorney General is proposing to create jobs by lowering the value of the dollar vs. the yuan (China’s currency) to make China’s products a lot more expensive for US consumers, who are already struggling to survive. Those higher prices then cause us to instead buy products made elsewhere, which will presumably means more American products get produced and sold. The trade off is most likely to be a few more jobs in return for higher prices (also called inflation), and a lower standard of living from the higher prices.

Fortunately there is an alternative that allows the US consumer to enjoy the enormous benefits of low cost imports and also makes good jobs available for all Americans willing and able to work. That alternative is to keep Federal taxes low enough so Americans have enough take home pay to buy all the goods and services we can produce at full employment levels AND everything the world wants to sell to us. This in fact is exactly what happened in 2000 when unemployment was under 4%, while net imports were $380 billion. We had what most considered a ‘red hot’ labor market with jobs for all, as well as the benefit of consuming $380 billion more in imports than we exported, along with very low inflation and a high standard of living due in part to the low cost imports.

The reason we had such a good economy in 2000 was because private sector debt grew at a record 7% of GDP, supplying the spending power we needed to keep us fully employed and also able to buy all of those imports. But as soon as private sector debt expansion reached its limits and that source of spending power faded, the right Federal policy response would have been to cut Federal taxes to sustain American spending power. That wasn’t done until 2003- two long years after the recession had taken hold. The economy again improved, and unemployment came down even as imports increased. However, when private sector debt again collapsed in 2008, the Federal government again failed to cut taxes or increase spending to sustain the US consumer’s spending power. The stimulus package that was passed almost a year later in 2009 was far too small and spread out over too many years. Consequently, unemployment continued to rise, reaching an unthinkable high of 16.9% (people looking for full time work who can’t find it) in March 2010.

The problem is we are conducting Federal policy on the mistaken belief that the Federal government must get the dollars it spends through taxes, and what it doesn’t get from taxes it must borrow in the market place, and leave the debts for our children to pay back. It is this errant belief that has resulted in a policy of enormous, self imposed fiscal drag that has devastated our economy.

My three proposals for removing this drag on our economy are:

1. A full payroll tax (FICA) holiday for employees and employers. This increases the take home pay for people earning $50,000 a year by over $300 per month. It also cuts costs for businesses, which means lower prices as well as new investment.

2. A $500 per capita distribution to State governments with no strings attached. This means $1.75 billion of Federal revenue sharing to the State of Connecticut to help sustain essential public services and reduce debt.

3. An $8/hr national service job for anyone willing and able to work to facilitate the transition from unemployment to private sector employment as the pickup in sales from my first two proposals quickly translates into millions of new private sector jobs.

Because the right level of taxation to sustain full employment and price stability will vary over time, it’s the Federal government’s job to use taxation like a thermostat- lowering taxes when the economy is too cold, and considering tax increases only should the economy ‘over heat’ and get ‘too good’ (which is something I’ve never seen in my 40 years).

For policy makers to pursue this policy, they first need to understand what all insiders in the Fed (Federal Reserve Bank) have known for a very long time- the Federal government (not State and local government, corporations, and all of us) never actually has nor doesn’t have any US dollars. It taxes by simply changing numbers down in our bank accounts and doesn’t actually get anything, and it spends simply by changing numbers up in our bank accounts and doesn’t actually use anything up. As Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke explained in to Scott Pelley on ’60 minutes’ in May 2009:

(PELLEY) Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?

(BERNANKE) It’s not tax money. The banks have– accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank, we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed.

Therefore, payroll tax cuts do NOT mean the Federal government will go broke and run out of money if it doesn’t cut Social Security and Medicare payments. As the Fed Chairman correctly explained, operationally, spending is not revenue constrained.

We know why the Federal government taxes- to regulate the economy- but what about Federal borrowing? As you might suspect, our well advertised dependence on foreigners to buy US Treasury securities to fund the Federal government is just another myth holding us back from realizing our economic potential.

Operationally, foreign governments have ‘checking accounts’ at the Fed called ‘reserve accounts,’ and US Treasury securities are nothing more than savings accounts at the same Fed. So when a nation like China sells things to us, we pay them with dollars that go into their checking account at the Fed. And when they buy US Treasury securities the Fed simply transfers their dollars from their Fed checking account to their Fed savings account. And paying back US Treasury securities is nothing more than transferring the balance in China’s savings account at the Fed to their checking account at the Fed. This is not a ‘burden’ for us nor will it be for our children and grand children. Nor is the US Treasury spending operationally constrained by whether China has their dollars in their checking account or their savings accounts. Any and all constraints on US government spending are necessarily self imposed. There can be no external constraints.

In conclusion, it is a failure to understand basic monetary operations and Fed reserve accounting that caused the Democratic Congress and Administration to cut Medicare in the latest health care law, and that same failure of understanding is now driving well intentioned Americans like Atty General Blumenthal to push China to revalue its currency. This weak dollar policy is a misguided effort to create jobs by causing import prices to go up for struggling US consumers to the point where we buy fewer Chinese products. The far better option is to cut taxes as I’ve proposed, to ensure we have enough take home pay to be able to buy all that we can produce domestically at full employment, plus whatever imports we want to buy from foreigners at the lowest possible prices, and return America to the economic prosperity we once enjoyed.

*This article first appeared on moslereconomics.com

Posted in Uncategorized, Unemployment

Tagged International Finance, The Trade Deficit, unemployment

The Coming European Debt Wars

By Michael Hudson

(Portions of this essay appeared in today’s Financial Times)

(Portions of this essay appeared in today’s Financial Times)

Government debt in Greece is just the first in a series of European debt bombs that are set to explode. The mortgage debts in post-Soviet economies and Iceland are more explosive. Although these countries are not in the Eurozone, most of their debts are denominated in euros. Some 87% of Latvia’s debts are in euros or other foreign currencies, and are owed mainly to Swedish banks, while Hungary and Romania owe euro-debts mainly to Austrian banks. So their government borrowing by non-euro members has been to support exchange rates to pay these private sector debts to foreign banks, not to finance a domestic budget deficit as in Greece.

All these debts are unpayably high because most of these countries are running deepening trade deficits and are sinking into depression. Now that real estate prices are plunging, trade deficits are no longer financed by an inflow of foreign-currency mortgage lending and property buyouts. There is no visible means of support to stabilize currencies (e.g., healthy economies). For the past year these countries have supported their exchange rates by borrowing from the EU and IMF. The terms of this borrowing are politically unsustainable: sharp public sector budget cuts, higher tax rates on already over-taxed labor, and austerity plans that shrink economies and drive more labor to emigrate.

Bankers in Sweden and Austria, Germany and Britain are about to discover that extending credit to nations that can’t (or won’t) pay may be their problem, not that of their debtors. No one wants to accept the fact that debts that can’t be paid, won’t be. Someone must bear the cost as debts go into default or are written down, to be paid in sharply depreciated currencies, but many legal experts find debt agreements calling for repayment in euros unenforceable. Every sovereign nation has the right to legislate its own debt terms, and the coming currency re-alignments and debt write-downs will be much more than mere “haircuts.”

There is no point in devaluing, unless “to excess” – that is, by enough to actually change trade and production patterns. That is why Franklin Roosevelt devalued the US dollar by 41% against gold in 1933, raising its official price from $20 to $35 an ounce. And to avoid raising the U.S. debt burden proportionally, he annulled the “gold clause” indexing payment of bank loans to the price of gold. This is where the political fight will occur today – over the payment of debt in currencies that are devalued.

Another byproduct of the Great Depression in the United States and Canada was to free mortgage debtors from personal liability, making it possible to recover from bankruptcy. Foreclosing banks can take possession of collateral real estate, but do not have any further claim on the mortgagees. This practice – grounded in common law – shows how North America has freed itself from the legacy of feudal-style creditor power and the debtors’ prisons that made earlier European debt laws so harsh.

The question is, who will bear the loss? Keeping debts denominated in euros would bankrupt much local business and real estate. Conversely, re-denominating these debts in local depreciated currency will wipe out the capital of many euro-based banks. But these banks are foreigners, after all – and in the end, governments must represent their own home electorates. Foreign banks do not vote.

Foreign dollar holders have lost 29/30th of the gold value of their holdings since the United States stopped settling its balance-of-payments deficits in gold in 1971. They now receive less than a thirtieth of this, as the price has risen to $1,100 an ounce. If the world can take that, why shouldn’t it take the coming European debt write-downs in stride?

There is growing recognition that the post-Soviet economies were structured from the start to benefit foreign interests, not local economies. For example, Latvian labor is taxed at over 50% (labor, employer, and social tax) – so high as to make it noncompetitive, while property taxes are less than 1%, providing an incentive toward rampant speculation. This skewed tax philosophy made the “Baltic Tigers” and central Europe prime loan markets for Swedish and Austrian banks, but their labor could not find well-paying work at home. Nothing like this (or their abysmal workplace protection laws) is found in the Western European, North American or Asian economies.

It seems unreasonable and unrealistic to expect that large sectors of the New European population can be made subject to salary garnishment throughout their lives, reducing them to a lifetime of debt peonage. Future relations between Old and New Europe will depend on the Eurozone’s willingness to re-design the post-Soviet economies on more solvent lines – with more productive credit and a less rentier-biased tax system that promotes employment rather than asset-price inflation that drives labor to emigrate. In addition to currency realignments to deal with unaffordable debt, the indicated line of solution for these countries is a major shift of taxes off labor onto land, making them more like Western Europe. There is no just alternative. Otherwise, the age-old conflict-of-interest between creditors and debtors threatens to split Europe into opposing political camps, with Iceland the dress rehearsal.

Until this debt problem is resolved – and the only way to resolve it is to negotiate a debt write-off – European expansion (the absorption of New Europe into Old Europe) seems over. But the transition to this future solution will not be easy. Financial interests still wield dominant power over the EU, and will resist the inevitable. Gordon Brown already has shown his colors in his threats against Iceland to illegally and improperly use the IMF as a collection agent for debts that Iceland doesn’t legally owe, and to blackball Icelandic membership in the EU.

Confronted with Mr. Brown’s bullying – and that of Britain’s Dutch poodles – 97% of Icelandic voters opposed the debt settlement that Britain and the Netherlands sought to force down the throat of Althing members last month. This high a vote has not been seen in the world since the old Stalinist era. It is only a foretaste. The choice that Europe ends up making will likely drive millions into the streets. Political and economic alliances will shift, currencies will crumble and governments will fall. The European Union and indeed, the international financial system will change in ways yet to be seen. This will be especially the case if nations adopt the Argentina model and refuse to make payment until steep discounts are made.

Paying in euros – for real estate and personal income streams in negative equity, where the debts exceed the current value of income flows available to pay mortgages or for that matter, personal debts – is impossible for nations that hope to maintain a modicum of civil society. “Austerity plans” IMF and EU style is an antiseptic, technocratic jargon for life-shortening and killing impact of gutting income, social services, spending on health on hospitals, education and other basic needs, and selling off public infrastructure for buyers to turn nations into “tollbooth economies” where everyone is obliged to pay access prices for roads, education, medical care and other costs of living and doing business that have long been subsidized by progressive taxation in North America and Western Europe.

The battle lines are being drawn regarding how private and public debts are to be repaid. For nations that balk at repayment in euros, the creditor nations have their “muscle” waiting in the wings: the credit rating agencies. At the first sign a nation is balking in paying in hard currency, or even at the first hint of it questioning a foreign debt as improper, the agencies will move in to reduce a nation’s credit rating. This will increase the cost of borrowing and threaten to paralyze the economy by starving it for credit.

The most recent shot was fired n April 6 when Moody’s downgraded Iceland’s debt from stable to negative. “Moody’s acknowledged that Iceland might still achieve a better deal in renewed negotiations, but said the current uncertainty was hurting the country’s short-term economic and financial prospects.”

The fight is on. It should be an interesting decade.

*Prof. Hudson is Chief Economic Advisor to the Reform Task Force Latvia (RTFL). His website is michael-hudson.com.

Operation Twist, Part Deux?

by Marshall Auerback and Rob Parenteau

Who funds our budget deficit? It is a question taking on increasing significance, given the recent back up on longer-dated bond yields, which has been explained by many as a “buyers’ strike” in response to growing government profligacy. We think this argument displays a seriously lagging understanding of how much modern money has changed since Nixon changed finance forever by closing the Gold window in 1973. Now that we’re off the gold standard, neither our international creditors, nor the so-called “bond market vigilantes”, “fund” anything, contrary to the completely false & misguided scare stories one reads almost daily in the press.

In his usually effective fashion, Bill Mitchell debunks the notion that “the markets” determine our interest rate structure, as opposed to the central banks. Mitchell discusses this in the context of his analysis of a BIS paper, “The Future of Public Debt: Prospects and Implications”, which raises the old canard about a potential “bond market buyers’ strike” as a consequence of rising public debt.” “[T]he debt ratio will explode in the absence of a sufficiently large primary surplus”, argues the author of the BIS paper.

From which – Mitchell deduces- “the governments [should] either stop allowing the bond markets to determine yields – that is, use their capacity to control the yield curve or, better still, abandon the practice of issuing debt.”

Mitchell then poses the question: “Why will yields spike dangerously so that real interest rates exceed real output growth rates? There is no answer to this question provided.”

There is no answer provided because, as a point of economic logic, Bill’s critique of the BIS is (as usual) unassailable. BUT as any regular observer of the markets can tell you, bonds have begun to rise again over the past few weeks, notably in the US. This might have occurred for the dumbest reasons imaginable (one person foolishly tried to link the rise in US yields to Portugal’s downgrade by the benighted ratings agencies).

On the other hand, one of the great insights of George Soros was the notion that markets could act on incorrect or imperfect information and thereby create a new kind of economic reality. It might well be that very few understand MMT or basic public reserve accounting, but that doesn’t alter the reality that bond yields have risen 20 basis points in the past week or so. And a central bank which is underpinned by a market fundamentalist ideology, coupled with a bunch of “big swinging dicks” in the trading pits is a potentially toxic combination. The Fed follows the price action at the long end of bond market. Long bond investors often try to force Fed’s hand. Around and around they go,dog chasing tail style.

There’s a power dynamic here – who’s really in control: Big Swinging Dick Finanzkapital (BSDF)or policy geeks who understand basic public reserve accounting?

The Fed clearly has a dilemma. It needs to finesse expectations management for BOTH Treasury bond and equity investors. Bond investors need to know they are not going to get screwed by inflation, so they want the fed funds rate renormalized. Equity investors want the “extended period” of ZIRP to last for, well, an extended period. Free money is good for specs.

So what’s a central banker like Bernanke to do?

How about a modern version of “Operation Twist”, which was implemented originally by the Fed in 1961 to flatten the yield curve in order to promote capital inflows and strengthen the dollar. The Fed utilized open market operations to shorten the maturity of public debt in the open market. It was only marginally successful back then.

So why should it work better today?

Well, the Fed has more tools in its policy box, thanks in part to its policy of paying interest on excess reserves (IOER). Scott Fullwiler has an excellent paper on this (“Paying Interest on Reserve Balances: It’s More Significant than You Think”), in which he demonstrates that this change in Fed policy has severed the relationship between the policy rate target and the level of reserves outstanding (if there ever was one – some indications in recent years were that all Fed had to do was announce new fed funds rate target, and primary dealers would take it there, knowing Fed had capacity to change reserves outstanding – all of which meant Fed did not have to change reserves, since they had a credible threat they could, making the textbook story about Fed ops even more outdated and incorrect).

So the Fed can tell everybody that they are renormalizing the fed funds rate and take the IOER up to 100bps. Note, the Fed does not need to remove any reserves to do this – they can just do it administratively. That’s how the IOER works – it severs the link between reserves in the system and the target policy rate, right?

Then, if the bond gods don’t rally Treasuries on the Fed’s efforts to renormalize the policy rate, Mr Bernanke calls up Bill Dudley (President at the NY Fed) and gives him instruction to buy all the 10 year UST on offer until the 10 year UST yield is down to, oh , say 3.5%. It is an open market operation, which the Fed performs all the time. They won’t have to call it QE, but it is in effect the same thing.

Then, every time some big swinging dick bond trader tries to push it above 3.5% by shorting Treasuries, the Fed slams their face into the concrete by having the open market desk buy the hell out of UST until the 10 year yield is back to 3.5%. Burn Fido enough times, yank his chain enough times, and like the Dog Whisperer, he gets it and stops.

No less than one of the leading “bond market vigilantes” has conceded this point. In his October 2003 Fed Focus, PIMCO’s Paul McCulley has acknowledged that “any market induced—foreign or domestic-driven—upward pressure on U. S. intermediate or long-term interest rates would/will be limited by the leash of the Fed’s . . . anchoring of the Fed funds rate . . . . Put differently, there is a limit to how steep the yield curve can get, if the Fed just says no—again and again!—to the tightening path implicit in a steep yield curve”.

What happens if the 10 year bond breaks out of the 3.5% to 4% range significantly even with no changes in expectations regarding the Fed? Could that happen, or is there some arbitrage mechanism that brings it back? Of course, there will always be smart bond traders (such as our friend, Warren Mosler), who will understand the potential arbitrage opportunity at hand and react accordingly, but a signal from the Fed that it desires a certain rate level or term structure for rates will facilitate the process.

Operation Twist, Part Deux, then? It strikes us as the optimal way to finesse the expectations management dilemma.

It seems to us that we are now approaching a very critical juncture in terms of potentially settling the debate between those who think that central banks establish the rate structure (as most readers of this blog believe) versus those who believe that this is done by the markets (such as the usual band of deficit hawks, and the writer of the BIS report critiqued by Bill Mitchell). Of course, like most MMT adherents, we feel that the whole debate would become less relevant if the US Treasury responded to today’s environment through sensible proactive fiscal expenditure, but it’s hard to sustain political support for that amidst sock puppet politicians who dole out goodies to their corporate contributors, and an Administration which genuinely believes we’re “running out of money”.

That places an unnecessarily large burden on the Fed, hardly an appealing prospect, given Mr Bernanke’s own neo-classical economics framework. Keynes himself was quite explicit about the importance of investor portfolio preferences in determining interest rates specifically. Indeed, Ch. 12 of “The General Theory” is all about the beauty contest aspect of asset price determination in the face of fundamental uncertainty and asset markets organized to optimize liquidity for existing holders. Does the Fed understand this? It may well not happen, but no question an aggressive move to counter short term portfolio preference shifts on the part of private investors could do much to resolve this “who determines rates” question once and for all.

There’s a power dimension here. Does the Fed really want to be led around by the nose by the very same people who created today’s economic disaster?

The Chinese Are Coming! The Chinese Are Coming! Oh My!

By Yeva Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray

One of the scare tactics in the toolbox of the deficit hawks is the argument that Chinese ownership of U.S. government bonds is dangerous, economically and politically. Portraying the government as a currency user akin to households, they argue that after reaching some debt to GDP threshold, sovereign governments face difficulties in finding takers for their debt so that they have to pay higher interest rates to compensate holders for higher risk of default. Indeed, it is frequently claimed that China is responsible for “financing” a huge portion of our federal government’s deficit—and that if China were to suddenly stop lending to Uncle Sam, he might be unable to finance his deficits except at usurious rates. So China controls Uncle Sam, holding his debt hostage.

This is nonsense.

The true effects of government deficits and debt on the economy have been discussed here and here. But these previous posts have not addressed in detail the distinction between domestic and foreign ownership of Treasury debt. In this post we would like to clarify what foreign ownership of treasury securities really means and whether it represents any real dangers for the U.S.

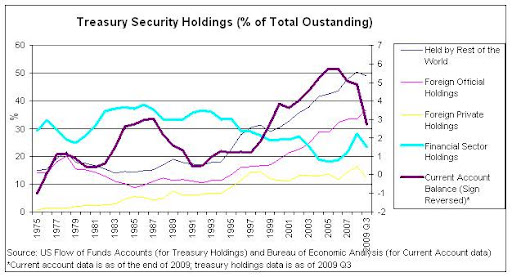

The following figure shows foreign ownership of US federal government debt, by percent of the total publicly held debt. The percent of the total held by foreigners has indeed been climbing—from less than 20% through the mid 1990s to nearly fifty percent today. Most of the growth is by “official” holders—foreign treasuries or central banks, now accounting for more than a third of all publicly held federal debt. This is supposed to represent US government ceding some measure of control over its purse strings to foreign governments.

The heavy purple line shows the US current account balance—largely made up of our trade deficit. (Note the sign is reversed: a deficit is shown as positive; a surplus is negative.) Since 1980 this had fluctuated near a range of minus 1 or 2 percent of GDP. However, after 1999 the current account balance plummeted to a negative 6% of GDP; while it has turned around to some extent during the global downturn, it was still nearly a negative three percent of GDP. Note that the rapid growth of foreign holding of treasuries coincided with the rapid growth of the current account deficit—a point we return to below.

The final (light blue) line plotted above shows domestic financial sector holdings of treasuries. This had been on a downward trend until the current global crisis—when a run to liquidity led financial institutions to increase purchases. Note also that financial sector holdings act as something like a buffer—when foreign demand is strong, US financial institutions reduce their share; when foreign demand is weak, US institutions increase their share. In recent months, the current account deficit has fallen dramatically; this has reduced foreign accumulation of dollar assets—with a small reduction of the percent of treasuries held by foreigners.

Of course, new issues of treasuries have increased with the growing budget deficit, and US financial institution holdings at first increased (the run to liquidity in the crisis). Foreign official holdings have also continued their climb. This could be because the US dollar is still seen as a refuge of safety, but more likely it is because nations still want to accumulate dollar reserves to protect their currencies. That is the other side of the liquidity crisis coin, of course—if there is a fear of a run to liquidity, exchange rates of countries thought to be riskier would face depreciation. Indeed, the graph shows that foreign official holdings of US treasuries began a long term trend in the late 1990s, after the Asian Tiger crisis. The lesson that seems to have been learned by at least some governments is that holding US treasuries offers protection to nations that try to peg their exchange rates.

The next figure displays the top foreign holders of US treasuries. While most public discussion has focused on Chinese holdings, Japanese holdings had been greater than Chinese holdings previous to 2008—and again surpassed those of China as of December 2009. Indeed, Japanese holdings reached nearly forty percent in the mid 2000s—far greater than the Chinese peak holdings. As we discussed above, there is a link between US current account deficits and foreign accumulation of US treasuries. Note also that the most recent data from China indicate that it ran an overall trade deficit; its accumulation of foreign assets must have slowed. It is too early to know whether this will continue—since it probably is due to relatively rapid growth in China in the context of a global recession. If it does, however, Chinese accumulation of US treasuries will probably slow.

Looking at it from the point of view of holders of dollar assets, their current account surpluses allow them to accumulate dollar-denominated assets. In the first instance, a trade surplus leads to dollar reserve credits (cash plus credits to reserve accounts at the Fed); since these balances have until very recently earned no interest they were most often exchanged for US treasuries and other financial assets. Thus, it is not surprising to observe a link among US trade deficits, foreign trade surpluses, and foreign accumulation of US treasuries. To put it concisely: Japan and China are big holders of foreign assets because they are exporters; and as the US is a target for their exports, dollar assets including US treasuries accumulate in Japan and China.

While this is usually presented as foreign “lending” to “finance” the US budget deficit, the correlation between US budget deficits and foreign accumulation of US treasuries does not actually demonstrate causation. The US current account deficit can just as well be taken as the source of foreign current account surpluses that can take the form of accumulations of US treasuries. In fact, by identity, the only way the rest of the world can net export to the US is if it accumulates an equal amount of US financial assets (adjusted by US official transactions). And it is the “propensity” (if not willingness) of the US to simultaneously run trade and government budget deficits that provides the wherewithal for foreign accumulation of treasuries. Obviously there must be a willingness on all sides for this to occur—we could say that it takes (at least) two to tango—and most public discussion ignores the fact that the Chinese desire to run a trade surplus with the US is linked to its desire to accumulate dollar assets. At the same time, the US budget deficit helps to generate domestic income that allows our private sector to consume and invest—some of which fuels imports, providing the income foreigners use to accumulate dollar saving—even as it generates treasuries accumulated by foreigners. So in this case, it takes three to tango.

In other words, the decisions cannot be independent—it makes no sense to talk of Chinese “lending” to the US without also taking account of Chinese desires to net export. Indeed all of the following are linked (possibly in complex ways): the willingness of Chinese to produce for export, the willingness of Chinese to accumulate dollar-denominated assets, the shortfall of Chinese domestic demand that allows China to run a trade surplus, the willingness of Americans to buy foreign products, the high level of US aggregate demand that results in a trade deficit, and the factors that result in a US government budget deficit. And of course it is even more complicated than this because we must bring in other nations as well as global demand taken as a whole.

While it is claimed that the Chinese might suddenly decide they do not want US treasuries any longer, at least one but more likely many of these other relationships would also need to change for that to happen. For example it is often said that China might decide it would rather accumulate Euros. While this could tend to promote more exports to the euro zone, there are complications on the financial side. For example, there is no equivalent to the US treasury in the eurozone. China could accumulate the euro-denominated debt of individual governments—say, Greece!—but these have different risk ratings. And with the sheer volume of Chinese exports, China’s purchases of national government euro debt further increases risk by driving down risk premiums—with China absorbing too much country-specific risk to feel comfortable purchasing individual euro nation debt.

Further, the euro nations, taken as a whole (and this is especially true of its strongest member, Germany) attempts to constrain domestic demand in order to promote exports. In other words, by design, Euroland will not passively allow itself to be a source of net demand for Chinese exports. Therefore if China sold its dollars and bought euros–weakening the dollar and strengthening the euro–it could lose more US exports than it would gain in euro zone exports. China would likely reverse course very quickly. A similar story can be told with respect to an attempt by China to export to Japan—another nation that relies heavily on exports—to accumulate Japanese government debt. And because China does seem to worry about capital losses on its dollar holdings, it would appear to have a low tolerance for dollar depreciation caused by its own actions. In other words, if it caused the euro or yen to rise relative to the dollar, it would quickly change policy to prop up the dollar. For these reasons, we seriously doubt any scenario in which China runs out of the dollar.

We are not arguing that the current situation will go on forever, although we do believe it will persist much longer than most commentators presume, based on our belief that China is intent on supporting its export sector. We are instead pointing out that changes are complex and that there are strong incentives against the sort of simple, abrupt, and dramatic shifts that are posited as likely scenarios. We expect that the complexity as well as the linkages among balance sheets and actions will ensure that transitions are more moderate that many observers currently expect.

Finally, many are concerned with the “interest burden” entailed in foreign ownership of US treasuries: the US is committed to making “costly” interest payments. Referring specifically to China, on an operational level it gets its dollars by selling goods and services to the US. When it gets paid it gets a credit balance in its reserve account at the Fed. Buying Treasury securities entails nothing more than shifting funds in China’s reserve account at the Fed to China’s securities account at the Fed. And when those securities mature, funds are simply shifted back to China’s reserve account at the Fed, with interest also credited to China’s reserve account.

Note that none of these transactions has anything to do with actual government spending, which operationally and independently consists of changing numbers upwards in the accounts of the recipients of government spending—and most of these are domestic residents and firms. The too often invoked imagery of ‘borrowing billions from China to fund health care and the war in Afghanistan and leaving the debt for our children to pay’ is at best an inapplicable absurdity. At worst our children will be simply doing nothing more than debiting and crediting accounts at the Fed just like we do and just like our mothers and fathers did before us. We don’t owe China anything more than a bank statement showing the accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank where their funds are recorded.

Finally, some worry that China might someday present its holdings of reserves and treasuries at the Fed to US exporters, converting its dollar claims to claims on US output. Yes, that could happen. If it does, the demand for US exports will be met by some complexly determined combination of dollar appreciation, rising prices of US exports, and a greater quantity of exports. The later two effects would almost certainly increase US production and hence employment. If there is any burden of Chinese ownership of US dollar assets, it is that US employment and exports to China could be higher. Ironically, most of those who fear US indebtedness to China would actually celebrate these impacts if they were to occur. (They do not understand that imports are a benefit and exports are a cost—but that is a topic we will leave for another day.)

In conclusion, it is time to put the fears about Chinese holdings of US treasuries to rest.

Marshall Auerback on Greece, the Euro and Fiscal Policy

Watch the video here.

Tell your representative to leave Social Security alone

SOCIAL SECURITY CANNOT GO INSOLVENT

By L. Randall Wray

Ok, here is the dumbest headline the NYTimes has run in recent days:

Social Security Payouts to Exceed Revenue This Year

By MARY WILLIAMS WALSH

The system is expected to pay out more in benefits this year than it receives in payroll taxes, a tipping point toward insolvency.

Social Security is a federal government program. Government pays Social Security benefits by crediting bank accounts. It can continue to do this even if payroll taxes fall to zero. The payment is an entry on the balance sheet of the Social Security recipient’s bank. Please write your representative and tell her or him to stop this nonsense right now.

Just as Wall Street went after healthcare, you can be sure that it is now going after Social Security. They hype is just starting. It comes in waves—whenever Wall Street loses a bundle, it looks to government bail-outs. What happened after the dot.com bust? Wall Street got President Bush to talk about an ownership society, proposing to dismantle Social Security to give households “ownership” over their own personal retirement accounts. The nonsense was obvious at the time: Wall Street had a big hole to fill, so it wanted households to “invest” payroll tax receipts in Wall Street managed accounts. That way, the same bozos who had just wiped out private savings by inducing gullible households to invest in pets.com would be able to wipe out retirements investing in other Wall Street schemes. Wall Street lost that round.

But now it is back. Wall Street’s latest excesses managed to destroy the economy. Those who lost their jobs or who had to take paycuts are paying less in FICA taxes. Hence, Social Security’s “revenues” are lower. That is a big boon to Wall Street—which will now whip up hysteria about Social Security’s looming bankruptcy. This is to direct attention away from the true insolvencies—which is all of the major private banks. It is also designed to scare the population about Social Security: will I ever get my Social Security pension?

Make no mistake about this. Unless voters tell their representatives to keep their dirty hands off Social Security, the Democrats and Republicans will work out a “compromise” to turn it over to Wall Street—just as they did with health insurance “reform” in the HIBOB (health insurer’s bail out bill). This is priority number one for Wall Street now, since it has lost trillions of dollars and is massively insolvent. It needs more government bail-out and it wants your Social Security.