By Michael Hudson

Europe is committing fiscal suicide – and will have little trouble finding allies at this weekend’s G-20 meetings in Toronto. Despite the deepening Great Recession threatening to bring on outright depression, European Central Bank (ECB) president Jean-Claude Trichet and Prime Ministers from Britain’s David Cameron to Greece’s George Papandreou (president of the Socialist International) and Canada’s host, Conservative Premier Stephen Harper, are calling for cutbacks in public spending.

The United States is playing an ambiguous role. The Obama Administration is all for slashing Social Security and pensions, euphemized as “balancing the budget.” Wall Street is demanding “realistic” write-downs of state and local pensions in keeping with the “ability to pay” (that is, to pay without taxing real estate, finance or the upper income brackets). These local pensions have been left unfunded so that communities can cut real estate taxes, enabling site-rental values to be pledged to the banks of interest. Without a debt write-down (by mortgage bankers or bondholders), there is no way that any mathematical model can come up with a means of paying these pensions. To enable workers to live “freely” after their working days are over would require either (1) that bondholders not be paid (“unthinkable”) or (2) that property taxes be raised, forcing even more homes into negative equity and leading to even more walkaways and bank losses on their junk mortgages. Given the fact that the banks are writing national economic policy these days, it doesn’t look good for people expecting a leisure society to materialize any time soon.

The problem for U.S. officials is that Europe’s sudden passion for slashing public pensions and other social spending will shrink European economies, slowing U.S. export growth. U.S. officials are urging Europe not to wage its fiscal war against labor quite yet. Best to coordinate with the United States after a modicum of recovery.

Saturday and Sunday will see the six-month mark in a carefully orchestrated financial war against the “real” economy. The buildup began here in the United States. On February 18, President Obama stacked his White House Deficit Commission (formally the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform) with the same brand of neoliberal ideologues who comprised the notorious 1982 Greenspan Commission on Social Security “reform.”

The pro-financial, anti-labor and anti-government restructurings since 1980 have given the word “reform” a bad name. The commission is headed by former Republican Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson (who explained derisively that Social Security is for the “lesser people”) and Clinton neoliberal Erskine Bowles, who led the fight for the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Also on the committee are bluedog Democrat Max Baucus of Montana (the pro-Wall Street Finance Committee chairman). The result is an Obama anti-change dream: bipartisan advocacy for balanced budgets, which means in practice to stop running budget deficits – the deficits that Keynes explained were necessary to fuel economic recovery by providing liquidity and purchasing power.

A balanced budget in an economic downturn means shrinkage for the private sector. Coming as the Western economies move into a debt deflation, the policy means shrinking markets for goods and services – all to support banking claims on the “real” economy.

The exercise in managing public perceptions to imagine that all this is a good thing was escalated in April with the manufactured Greek crisis. Newspapers throughout the world breathlessly discovered that Greece was not taxing the wealthy classes. They joined in a chorus to demand that workers be taxed more to make up for the tax shift off wealth. It was their version of the Obama Plan (that is, old-time Rubinomics).

On June 3, the World Bank reiterated the New Austerity doctrine, as if it were a new discovery: The way to prosperity is via austerity. “Rich counties can help developing economies grow faster by rapidly cutting government spending or raising taxes.” The New Fiscal Conservatism aims to corral all countries to scale back social spending in order to “stabilize” economies by a balanced budget. This is to be achieved by impoverishing labor, slashing wages, reducing social spending and rolling back the clock to the good old class war as it flourished before the Progressive Era.

The rationale is the discredited “crowding out” theory: Budget deficits mean more borrowing, which bids up interest rates. Lower interest rates are supposed to help countries – or would, if borrowing was for productive capital formation. But this is not how financial markets operate in today’s world. Lower interest rates simply make it cheaper and easier for corporate raiders or speculators to capitalize a given flow of earnings at a higher multiple, loading the economy down with even more debt!

Alan Greenspan parroted the World Bank announcement almost word for word in a June 18 Wall Street Journal op-ed. Running deficits is supposed to increase interest rates. It looks like the stage is being set for a big interest-rate jump – and corresponding stock and bond market crash as the “sucker’s rally” comes to an abrupt end in months to come.

The idea is to create an artificial financial crisis, to come in and “save” it by imposing on Europe and North America “Greek-style” cutbacks in social security and pensions. For the United States, state and local pensions in particular are to be cut back by “emergency” measures to “free” government budgets.

All this is quite an inversion of the social philosophy that most voters hold. This is the political problem inherent in the neoliberal worldview. It is diametrically opposed to the original liberalism of Adam Smith and his successors. The idea of a free market in the 19th century was one free from predatory rentier financial and property claims. Today, a “free market” (Alan Greenspan and Ayn Rand style) is a market free for predators. The world is being treated to a travesty of liberalism and free markets.

This shows the usual ignorance of how interest really are set – a blind spot which is a precondition for being approved for the post of central banker these days. Ignored is the fact that central banks determine interest rates. Under the ECB rules, national central banks can no longer do this. Yet that is precisely what central banks were created to do. As a result, European governments are obliged to borrow at rates determined by financial markets.

This financial stranglehold threatens either to break up Europe or to plunge it into the same kind of poverty that the EU is imposing on the Baltics. Latvia is the prime example. Despite a plunge of over 20% in its GDP, its government is running a budget surplus, in the hope of lowering wage rates. Public-sector wages have been driven down by over 30%, and the government expresses the hope for yet further cuts – spreading to the private sector. Spending on hospitals, ambulance care and schooling has been drastically cut back.

What is missing from this argument? The cost of labor can be lowered by a classical restoration of progressive taxes and a tax shift back onto property – land and rentier income. Instead, the cost of living is to be raised, by shifting the tax burden further onto labor and off real estate and finance. The idea is for the economic surplus to be pledged for debt service.

In England, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has described a “euro mutiny” against regressive fiscal policy. But it is more than that. Beyond merely shrinking the economy, the neoliberal aim is to change the shape of the trajectory along which Western civilization has been moving for the past two centuries. It is nothing less than to roll back Social Security and pensions for labor, health care, education and other public spending, to dismantle the social welfare state, the Progressive Era and even classical liberalism.

So we are witnessing a policy long in the planning, now being unleashed in a full-court press. The rentier interests, the vested interests that a century of Progressive Era, New Deal and kindred reforms sought to subordinate to the economy at large, are fighting back. And they are in control, with their own representatives in power – ironically, as Social Democrats and Labour party leaders, from President Obama here to President Papandreou in Greece and President Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero in Spain.

Having bided their time for the past few years the global predatory class is now making its move to “free” economies from the social philosophy long thought to have been built into the economic system irreversibly: Social Security and old-age pensions so that labor didn’t have to be paid higher wages to save for its own retirement; public education and health care to raise labor productivity; basic infrastructure spending to lower the costs of doing business; anti-monopoly price regulation to prevent prices from rising above the necessary costs of production; and central banking to stabilize economies by monetizing government deficits rather than forcing the economy to rely on commercial bank credit under conditions where property and income are collateralized to pay the interest-bearing debts culminating in forfeitures as the logical culmination of the Miracle of Compound Interest.

This is the Junk Economics that financial lobbyists are trying to sell to voters: “Prosperity requires austerity.” “An independent central bank is the hallmark of democracy.” “Governments are just like families: they have to balance the budget.” “It is all the result of aging populations, not debt overload.” These are the oxymorons to which the world will be treated during the coming week in Toronto.

It is the rhetoric of fiscal and financial class war. The problem is that there is not enough economic surpluses available to pay the financial sector on its bad loans while also paying pensions and social security. Something has to give. The commission is to provide a cover story for a revived Rubinomics, this time aimed not at the former Soviet Union but here at home. Its aim is to scale back Social Security while reviving George Bush’s aborted privatization plan to send FICA paycheck withholding into the stock market – that is, into the hands of money managers to stick into an array of junk financial packages designed to skim off labor’s savings.

So Mr. Obama is hypocritical in warning Europe not to go too far too fast to shrink its economy and squeeze out a rising army of the unemployed. His idea at home is to do the same thing. The strategy is to panic voters about the federal debt – panic them enough to oppose spending on the social programs designed to help them. The fiscal crisis is being blamed on demographic mathematics of an aging population – not on the exponentially soaring private debt overhead, junk loans and massive financial fraud that the government is bailing out.

What really is causing the financial and fiscal squeeze, of course, is the fact that that government funding is now needed to compensate the financial sector for what promises to be year after year of losses as loans go bad in economies that are all loaned up and sinking into negative equity.

When politicians let the financial sector run the show, their natural preference is to turn the economy into a grab bag. And they usually come out ahead. That’s what the words “foreclosure,” “forfeiture” and “liquidate” mean – along with “sound money,” “business confidence” and the usual consequences, “debt deflation” and “debt peonage.”

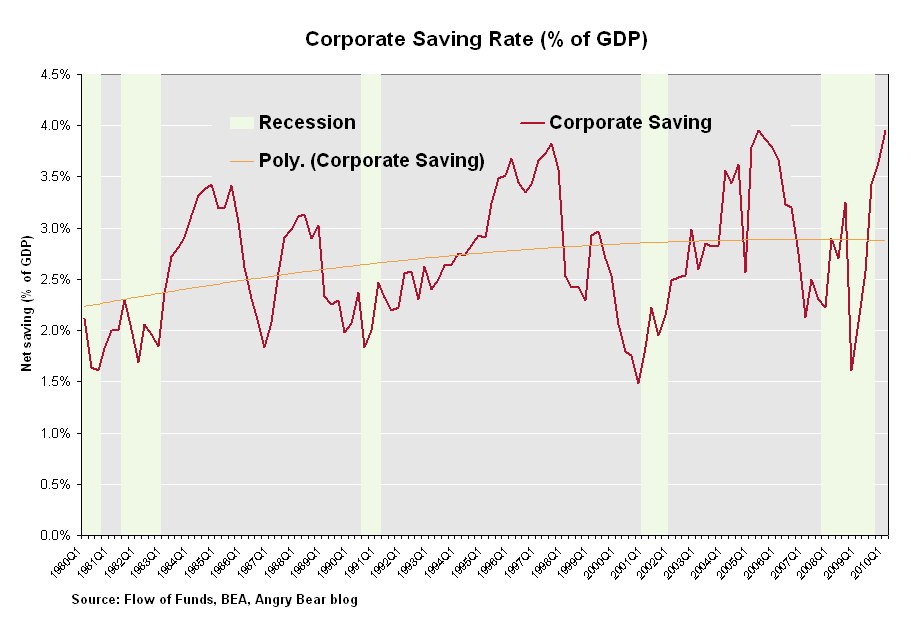

Somebody must take a loss on the economy’s bad loans – and bankers want the economy to take the loss, to “save the financial system.” From the financial sector’s vantage point, the economy is to be managed to preserve bank liquidity, rather than the financial system run to serve the economy. Government social spending (on everything apart from bank bailouts and financial subsidies) and disposable personal income are to be cut back to keep the debt overhead from being written down. Corporate cash flow is to be used to pay creditors, not employ more labor and make long-term capital investment.

The economy is to be sacrificed to subsidize the fantasy that debts can be paid, if only banks can be “made whole” to begin lending again – that is, to resume loading the economy down with even more debt, causing yet more intrusive debt deflation.

This is not the familiar old 19th-century class war of industrial employers against labor, although that is part of what is happening. It is above all a war of the financial sector against the “real” economy: industry as well as labor.

The underlying reality is indeed that pensions cannot be paid – at least, not paid out of financial gains. For the past fifty years the Western economies have indulged the fantasy of paying retirees out of purely financial gains (M-M’ as Marxists would put it), not out of an expanding economy (M-C-M’, employing labor to produce more output). The myth was that finance would take the form of productive loans to increase capital formation and hiring. The reality is that finance takes the form of debt – and gambling. Its gains therefore were made from the economy at large. They were extractive, not productive. Wealth at the rentier top of the economic pyramid shrank the base below. So something has to give. The question is, what form will the “give” take? And who will do the giving – and be the recipients?

The Greek government has been unwilling to tax the rich. So labor must make up the fiscal gap, by permitting its socialist government to cut back pensions, health care, education and other social spending – all to bail out the financial sector from an exponential growth that is impossible to realize in practice. The economy is being sacrificed to an impossible dream. Yet instead of blaming the problem on the exponential growth in bank claims that cannot be paid, bank lobbyists – and the G-20 politicians dependent on their campaign funding – are promoting the myth that the problem is demographic: an aging population expecting Social Security and employer pensions. Instead of paying these, governments are being told to use their taxing and credit-creating power to bail out the financial sector’s claims for payment.

Latvia has been held out as the poster child for what the EU is recommending for Greece and the other PIIGS: Slashing public spending on education and health has reduced public-sector wages by 30 percent, and they are still falling. Property prices have fallen by 70 percent – and homeowners and their extended family of co-signers are liable for the negative equity, plunging them into a life of debt peonage if they do not take the hint and emigrate.

The bizarre pretense for government budget cutbacks in the face of a post-bubble economic downturn is that it will help to rebuild “confidence.” It is as if fiscal self-destruction can instill confidence rather than prompting investors to flee the euro. The logic seems to be the familiar old class war, rolling back the clock to the hard-line tax philosophy of a bygone era – rolling back Social Security and public pensions, rolling back public spending on education and other basic needs, and above all, increasing unemployment to drive down wage levels. This was made explicit by Latvia’s central bank – which EU central bankers hold up as a “model” of economic shrinkage for other countries to follow.

It is a self-destructive logic. Exacerbating the economic downturn will reduce tax revenues, making budget deficits even worse in a declining spiral. Latvia’s experience shows that the response to economic shrinkage is emigration of skilled labor and capital flight. Europe’s policy of planned economic shrinkage in fact controverts the prime assumption of political and economic textbooks: the axiom that voters act in their self-interest, and that economies choose to grow, not to destroy themselves. Today, European democracies – and even the Social Democratic, Socialist and labour Parties – are running for office on a fiscal and financial policy platform that opposes the interests of most voters, and even industry.

The explanation, of course, is that today’s economic planning is not being done by elected representatives. Planning authority has been relinquished to the hands of “independent” central banks, which in turn act as the lobbyists for commercial banks selling their product – debt. From the central bank’s vantage point, the “economic problem” is how to keep commercial banks and other financial institutions solvent in a post-bubble economy. How can they get paid for debts that are beyond the ability of many people to pay, in an environment of rising defaults?

The answer is that creditors can get paid only at the economy’s expense. The remaining economic surplus must go to them, not to capital investment, employment or social spending.

This is the problem with the financial view. It is short-term – and predatory. Given a choice between operating the banks to promote the economy, or running the economy to benefit the banks, bankers always will choose the latter alternative. And so will the politicians they support.

Governments need huge sums to bail out the banks from their bad loans. But they cannot borrow more, because of the debt squeeze. So the bad-debt loss must be passed onto labor and industry. The cover story is that government bailouts will permit the banks to start lending again, to reflate the Bubble Economy’s Ponzi-borrowing. But there is already too much negative equity and there is no leeway left to restart the bubble. Economies are all “loaned up.” Real estate rents, corporate cash flow and public taxing power cannot support further borrowing – no matter how much wealth the government gives to banks. Asset prices have plunged into negative equity territory. Debt deflation is shrinking markets, corporate profits and cash flow. The Miracle of Compound Interest dynamic has culminated in defaults, reflecting the inability of debtors to sustain the exponential rise in carrying charges that “financial solvency” requires.

If the financial sector can be rescued only by cutting back social spending on Social Security, health care and education, bolstered by more privatization sell-offs, is it worth the price? To sacrifice the economy in this way would violate most peoples’ social values of equity and fairness rooted deep in Enlightenment philosophy.

That is the political problem: How can bankers persuade voters to approve this under a democratic system? It is necessary to orchestrate and manage their perceptions. Their poverty must be portrayed as desirable – as a step toward future prosperity.

A half-century of failed IMF austerity plans imposed on hapless Third World debtors should have dispelled forever the idea that the way to prosperity is via austerity. The ground has been paved for this attitude by a generation of purging the academic curriculum of knowledge that there ever was an alternative economic philosophy to that sponsored by the rentier Counter-Enlightenment. Classical value and price theory reflected John Locke’s labor theory of property: A person’s wealth should be what he or she creates with their own labor and enterprise, not by insider dealing or special privilege.

This is why I say that Europe is dying. If its trajectory is not changed, the EU must succumb to a financial coup d’êtat rolling back the past three centuries of Enlightenment social philosophy. The question is whether a break-up is now the only way to recover its social democratic ideals from the banks that have taken over its central planning organs.