By Marshall Auerback

Deficit spending by the government is merely the counterpart of private sector saving. What government deficit spending does is to permit the private sector to achieve its level of desired saving. When the latter changes, government spending ought to be adjusting in the opposite direction to offset it (unless the current account balance happens to do the job).

But consider the implications of what happens if one the economy’s three major sectors – in this case, the corporate sector – retains savings above and beyond that required to reinvest and establish growth in the productive economy.

If one examines recent cases in which the corporate sector remained a net saver, both the Japanese and Canadian experiences spring to mind. Even today, Japan’s corporate sector remains the largest repository of non-government savings, yet employment growth is virtually non-existent. Similarly, during the 1990s, the Canadian household sector was a net lender in the 1980s and 1990s and the corporate sector was a net borrower. So the biggest adjustment that came via Canada’s export boom was a huge increase in corporate savings during the years of Paul Martin’s fiscal austerity drive. But these savings were not really deployed aggressively for reinvestment in the productive economy and, hence, job creation.

As Professor Mario Seccareccia of the University of Ottawa has noted in a recent paper, in Canada during the latter half of the 1990s and during the subsequent decade, the corporate sector began to act like Keynes’s economic rentiers (“The Role of Public Investment in a Coordinated “Exit Strategy” to Promote Long-Term Growth: The Keynes Legacy”). An implication to be drawn from this analysis is that even when corporations build up massive savings, as they are now doing in Japan (and as they did in Canada in the mid-1990s), one ought to pose the question: if those profits are not being reinvested to create further job growth, shouldn’t the government tax them, so that it can use the fiscal resources itself to move policy in that direction?

As Seccareccia notes in the Canadian context, massive build ups of cash flow can and did facilitate all sorts of mischief – zaitech (i.e. financial engineering), accounting frauds, control fraud:

“[T]his reversal of the net lending/borrowing position of the business and household sectors is of critical importance in understanding the evolution of financial capitalism over the last decade, with much of the speculative drive having been fueled by the growing savings of the corporate sector. It was the rentier behaviour of the corporate sector, with the latter finding it ever more lucrative to engage in financial acquisitions, which largely led to an abandoning of productive investment since the 1990s.”

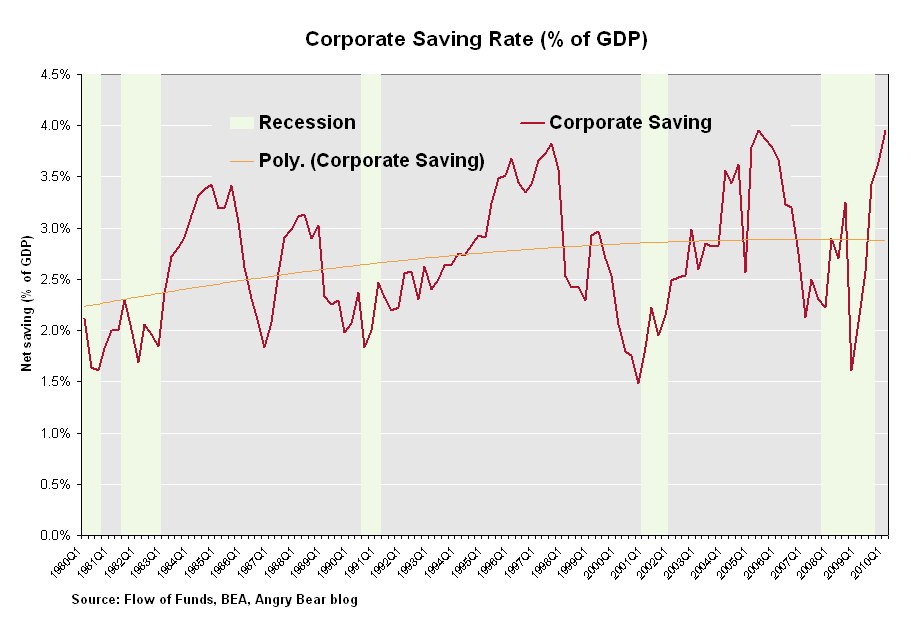

In this context, the entire economy becomes financialised and therefore far less productive and more prone to fraud and higher rates of unemployment. We see evidence of this in figure 1, which shows that recessions have been preceded by a build-up of corporate savings. But it serves the interests of the economic rentiers. This is exactly what happened in Canada and has happened all over the world in the past decade.

It is true that taxing the savings of the corporate rentiers in itself will not necessarily lead to more spending in the economy. And from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, it is also the case that the government does not “need” the so-called fiscal resources to spend. The government is never revenue constrained per se and could easily do more regardless of its take on corporate tax receipts.

In making this concession, my point was not that corporate tax receipts are required for the government to spend, but more that the threat of taxation might induce the corporate sector to do some of the government’s “heavy lifting” on the job creation front. There’s some political advantage here because, as we are witnessing today, there are profoundly strong forces currently mobilizing against government spending on the spurious grounds of “fiscal sustainability.”

So let’s call their bluff.

There are additional social benefits to be derived from this proposal. If the government taxes excess corporate savings, it means there are fewer corresponding opportunities for corporate financial engineering, control frauds, etc., and therefore greater financial stability as you have an economy less prone to financialisation. That’s an unalloyed social good.

In effect, this becomes a tax aimed explicitly at the corporate rentiers who are not reinvesting their super profits in tangible capital equipment, except in tech/telecom bubbles, or in Chinese malinvestment schemes, etc. And it serves an ideological purpose of a) forcing nonfinancial capitalists to, well, be capitalists, not speculators, and b) ties the deficit reduction initiatives, which, as we have argued many times in the past, are insane and suicidal, but are nonetheless being carried out, to making the rentiers pay their “fair share.”

The deficit hawks have gained significant policy traction, but we need to perform whatever jiu jitsu we can to point the finger at the real source of the so called “savings glut”, which is lack of corporate reinvestment in anything but zaitech, payouts, financial engineering, and other delights of casino capitalism. We have to demystify what it means to have the whole system geared to serve “shareholder value,” and we have to demonstrate that capitalists are failing to serve their role before a large consensus behind public and public/private investment initiatives can be rebuilt from the ashes of Austeria.

It appears that massive build ups of cash flow facilitate all sorts of mischief – zaitech (i.e. financial engineering), accounting frauds, control fraud, etc. And this would be about the time modern compensation systems began to change, tying, more and more, management bonuses to share price. So you see firms “investing” their earnings in massive buybacks of their own stocks.

In Canada, the reversal of the net lending/borrowing position of the business and household sectors is of critical importance in understanding the evolution of financial capitalism over the last decade, with much of the speculative drive having been fueled by the growing savings of the corporate sector. It was the rentier behaviour of the corporate sector, with the latter finding it ever more lucrative to engage in financial acquisitions, which largely led to an abandoning of productive investment since the 1990s.

When an economy becomes financialised and therefore far less productive, it becomes more prone to fraud, greater financial instability, and higher rates of unemployment. But it serves the interests of the economic rentiers. Minsky was right: you need a “big government” to act as a stabilising bulwark against the financialisation of the economy. Taxing retained corporate earnings is clearly another aspect of dealing with the ravages of money market capitalism.

17 responses to “SHOULD WE TAX EXCESS CORPORATE PROFITS?”