By L. Randall Wray

In Part 1 I argued that Beltway progressives aided and abetted deficit hawk Pete Peterson in his efforts to gut the last remaining vestiges of Roosevelt’s New Deal. By adopting Peterson’s views on government finances, they were unable to provide a progressive alternative to budget cuts. Since Republicans were willing to make a Custer’s Last Stand on the debt limit, and since President Obama was Wall Street’s designate to privatize healthcare and retirement, Democrats needed that progressive voice. But Beltway progressives had already caved, for reasons I discussed.

Indeed, it appears even worse than that. Yves Smith already blew the whistle on three progressive research groups (Roosevelt Institute, Economic Policy Institute, and the Center for American Progress) that produced reports with funding from Peterson. These reports adopted the deficit hysterian’s argument that the US budget is on an “unsustainable” course, and advocated a return to “fiscal responsibility”. Getting progressives to adopt neoliberal terminology was a real coup for the deficit hawks. With such hyped-up talk, there was no doubt that Obama would be able to put Social Security and Medicare on the chopping block.

I have recently discussed what I see to be problems with the Roosevelt Institute’s report over at FDL. This was also the main target of Yves. (Go here).

Let me say, however, that I think critics have been too hard on these three groups. I have argued that taking tainted money from Peterson can be justified if one uses the money to produce progressive research. I am sure all three groups believe that is precisely what they did—they thought they would get a progressive view into the debate, something that had been sadly lacking. In their budgeting exercises, they preserved what they saw to be progressive programs, they budgeted some new progressive programs, and they shifted tax burdens to higher income individuals and corporations. Surely, they believed, that is better than standing on the sidelines and letting Peterson choose which programs to cut? I get that. I sympathize with them.

But here’s the problem. They accepted—at least implicitly—the Peterson agenda. Deficits and debt ratios have to be reduced, if not immediately then eventually. In other words, they budgeted, but with Peterson’s Austerian constraints.

I do not know if Peterson demanded that they submit budget projections that showed debt and deficit reduction relative to the base case. But the RI proudly displays on the report’s homepage projections of very significant debt reduction relative to the “do nothing” baseline. (see here) In other words, they accepted the premise that debt and deficit ratios should be reduced. Once that is done, there is nothing to do but cut some programs and raise taxes.

Part 1 should have made clear, however, that progressives had already moved very close to the Peterson view before he put them on the payroll. For a variety of reasons they had already adopted a “deficit dove” position. The difference between a hawk and a dove is this: hawks want deficit reduction more-or-less immediately. Many of them hold the position that deficits are always bad because they always cause inflation and slow economic growth. The extreme hawk position is that even now, with official unemployment above 9%, government spending should be reduced. There is no plausible economic theory standing behind that position—it is ideological, or as Representative Ryan put it, it is a “moral” position. More “reasonable” hawks are willing to wait until a stronger recovery gets underway. Even Pete Peterson is on record favoring postponement of deficit-cutting until 2012 (see below).

By contrast, deficit doves believe that deficits are not only OK in a deep recession, they are even necessary. (Prominent deficit doves include Paul Krugman as well as many of the writers at New Deal 2.0 as well as individuals at the three institutions that accepted Peterson’s funds.) However, doves believe that “eventually” deficits need to be cut so that debt stops growing; they typically want to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at some level. Some admit that the choice of a final resting place for the debt ratio is somewhat arbitrary—perhaps it should be 60%, or perhaps 100%. But doves are sure that 200% is worse than 100%, and that 100% is worse than 60%. Thus, “eventually” deficits must be cut—and that means hard choices.

A progressive dove can be identified by her preferred means of obtaining that final “sustainable” debt ratio. Tax increases on the rich and on corporations are good. Reductions in military spending and subsidies for corporate agriculture and oil companies are advocated. Raising taxes on the poor and cutting their benefits are rejected by progressive doves.

The problem is that most progressives accept the intergenerational warrior’s claim that “entitlements” (Roosevelt’s New Deal) will bankrupt the nation 25 to 50 years down the road. And those portions of the budget are already large and growing. Hence, as Peterson and his minions have argued for years, “TINA”—there is no alternative to hacking away at entitlements.

The more progressive doves advocate relatively small tweaks to Social Security (raising or eliminating the “cap” so that higher income folks contribute more payroll taxes; raising the retirement age; taxing benefits received by high income retirees; reducing the COLAs; and so on) or bigger tweaks to Medicare and Medicaid (greater emphasis on cost control—some go so far as to recommending the “public option”—or to slow health care cost growth more generally, using centralized bargaining over drug prices). The game played then becomes one of finding the least painful way to reduce longer-term budget deficits and growth of debt in order to move the government’s finances back toward “fiscal responsibility”.

That was a long excursion by way of introduction to what follows—an examination of EPI’s “progressive budget”. I want to make clear three points about EPI. First, EPI’s progressive credentials are not in question. It is without doubt the most important progressive voice in Washington. Second, EPI’s preferred budget was created before it accepted any Peterson money. I will actually refer to the budget it published in 2010, long before Peterson solicited EPI to produce a report. In all important respects, the earlier budget is the same as the budget EPI produced for Peterson. Thus, those critics who have argued that EPI “sold out” to get Peterson funds are wrong.

And, finally, I want to say that much of the budget is indeed “progressive”—it preserves progressive programs, it adds funding for new progressive programs, and it shifts taxes to higher income individuals and corporations. It obtains deficit and debt reduction mostly by increasing taxes. We could quibble over the allocation of funds or the budget priorities of EPI, but I have no problem agreeing that the priorities are consistent with a progressive agenda—albeit not necessarily one I would endorse. Further, EPI has been steadfast in its protection of Social Security. Unlike some other progressives, for example, EPI has rejected any attempt to cut benefits by raising retirement ages or fiddling with COLAs. So I want to make clear that when I criticize Beltway progressives for aiding Social Security’s enemies I am not including EPI, which has been a strong voice in support of Social Security.

Before closely examining EPI’s report let me quickly summarize my complaints about Beltway progressives:

- By adopting a deficit dove position, they legitimize the Peterson crowd’s focus on deficit ratios and debt ratios;

- By adopting the intergenerational warrior’s long-term budgeting methods, they legitimize the fear-mongering surrounding “unfunded entitlements”;

- This leads inexorably to weakening support for New Deal social programs by questioning their “affordability”; and

- More generally, it legitimizes the arguments of fiscal conservatives who want to reduce the role of government in the economy.

For the purposes of my analysis, I will compare an EPI report from 2010 (before EPI received funding from Peterson) with a Peterson-funded report from 2009, both of which provided “blueprints” for deficit and debt reduction. As one might expect, the dovish EPI report preserves and even enhances spending on progressive programs, while raising taxes on higher income individuals and corporations. The Peterson report is much more hysterical about a looming financial crisis if we do not do something immediately about unfunded entitlements. Further, the EPI budget would move toward deficit cutting much more slowly, and would stabilize the debt ratio at a higher level.

Still, as one reads the EPI report, one is struck by two things. First, both the goals of the research exercise as well as the major points made are remarkably similar to the earlier Peterson diatribe on the coming fiscal crisis: medium-term and longer-term deficits and debt ratios need to be reduced. I will next examine those similarities. Second, while EPI adopts a dovish position on budget deficits and debt, it offers no serious argument to justify that position. It simply takes as granted the belief that rising debts and deficits are bad, and the bigger they are the badder they are. I surmise that EPI simply presumes that everyone “knows” government deficits and debt are bad, so no explanation is required. Everyone, that is, within the Washington beltway. I suppose that because they all breathe the same hyperventilator’s air, it is just so obvious that Beltway progressives do not need to consider the assumption that the US is on an “unsustainable” course.

The EPI 2010 report provides the following summary of its “blueprint” for a progressive approach to budgeting that adopts a “sound fiscal path”:

1. Jobs first. Jobs and economic growth are essential to our capacity to reduce deficits, and there should be no across-the-board spending reductions until the economy fully recovers. In fact, efforts to spur job creation today will put us on a better economic path and create a solid revenue base. We believe there should be no consideration of overall spending reductions until unemployment has fallen to 6% and remained at or below that level for six months. 2. Stabilize debt. Over the long term, national debt as a share of the economy should be stabilized and eventually brought onto a downward trajectory. 3. Build on economy-boosting investments. We must build and maintain initiatives that directly support long-term job and economic growth. Failing to invest adequately in these efforts – or sacrificing them to short-term deficit reduction – would be a dereliction of sound public management. 4. Target revenue increases. Revenue increases should come primarily from those who have benefited most from the economic gains of the last few decades. 5. No cost shifting. Debt reduction must be weighed against other economic priorities. Policies that simply shift costs from the federal government to individuals and families may improve the government’s balance sheet but would worsen the condition of many Americans, leaving the overall economy no better off.…. We document the hard choices that need to be made and suggest specific policies that will yield lower deficits and a sustainable debt while preserving essential initiatives and investments. (p. V)

Note that of the 5 bullet points that summarize the blueprint, three address the supposed debt and deficit problems. Bullet 2 argues for stabilizing and then reducing the debt ratio; Bullet 4 argues for increasing tax revenues; and Bullet 1 postpones blood-letting through spending reductions until unemployment falls to 6%. It is also important to note, however, that EPI recognizes that it does no good to shift debt from government to households—so, for example, reducing Medicare costs by putting them on households only reduces government deficits and debt by increasing household deficits and debt.

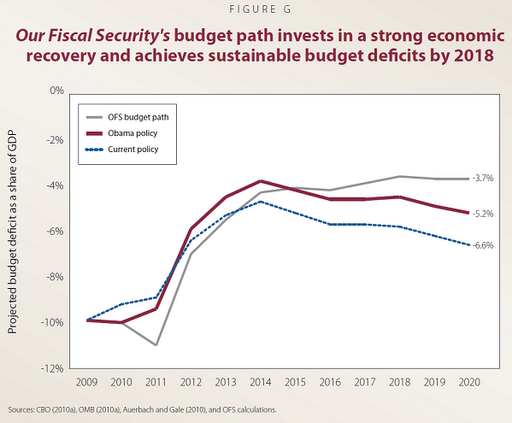

Let us look at EPI’s projections, that compare the “do nothing” scenario against Obama’s proposals and the EPI proposals (labeled “OFS” for “our fiscal security”). This graph shows that EPI’s proposals will cut the deficit to GDP ratio by almost half over the medium term.

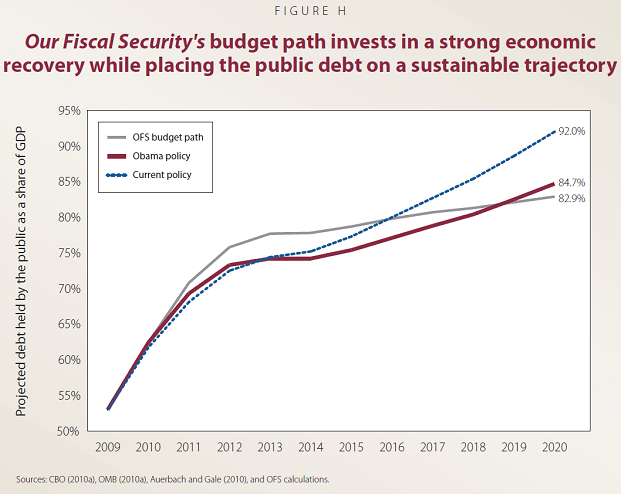

The next graph compares the medium term debt-to-GDP ratios under the three scenarios:

What is the source of the government’s financial problems? Rising healthcare costs and lack of adequate tax revenue. (“Any realistic solution to the long-term budget outlook must confront the real drivers of the growth of the national debt, namely the rapid rise in health care costs and the lack of adequate revenue.”, p. 2). It is important to note here that EPI wants to protect Social Security benefits—it does not advocate any cuts. So to close the “fiscal gap” it recommends higher payroll taxes by raising the “cap”. It tweaks “Obamacare” to reduce the rate of growth of health insurance costs. (Interested readers can go to the report. While I do not support either of these proposals, one could label them “progressive” given the narrow range of what passes for progressive discourse in America.) In summary, their proposal achieves deficit and debt reduction (relative to current policy):

Our suggested budget blueprint achieves lower deficits in the medium term and balances the primary federal budget (the year’s current revenue and spending, not counting interest payments on past debt) in less than a decade. This path recognizes the need to increase revenue while targeting certain areas for reductions in spending; in particular, our proposed path reallocates spending away from the Department of Defense by adopting common sense spending reductions. Finally, the blueprint protects core priorities such as Social Security and health care from economically counterproductive reductions in benefits. The net impact of the spending and revenue adjustments we put forth in this blueprint will produce the following short- and long-term results: • Substantial and sustained increased funding for job creation and investments, especially in the near term; • A budget path that significantly improves the 10-year budget window; • A transition from a primary deficit to a primary surplus in 2018, and sustainable debt levels by the end of the decade; • An improvement in the path for public debt in the long term (stabilizing debt as a share of the economy beyond 2025); • A solid footing for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid for the long term; • A modernized tax code that raises adequate revenue fairly and efficiently.

The following figure shows a significantly lower long-term debt trajectory as a result of EPI’s proposals.

Throughout the report, EPI refers to “fiscal security”, “fiscal responsibility”, a “sound fiscal path”, “sustainable debt”, and the current “unsustainability of the national budget”. None of these terms is ever adequately defined.

The report also discusses the “75 year fiscal gap”, that must be reduced to “stabilize the debt ratio at today’s level”, requiring tax increases or spending reductions amounting to 7-9% of GDP. It warns that the government is not raising sufficient revenue to cover its expenses and that we cannot face national challenges without adequate funding and a return to fiscal responsibility. I will return to these claims below.

It is interesting to compare the EPI Blueprint with the Peterson-Pew Commission’s report from 2009. The Peterson report is cited as a source for the EPI blueprint, and shares similar phrasing and analysis. Like the EPI Blueprint, the Peterson report advocates a return to “fiscal responsibility”, and the need to “return to a sustainable path”. And like the EPI, the Peterson group is committed to stabilizing the public debt over the medium term and then reducing the debt ratio over the long term. The Peterson report also attributes the fiscal problems to growing healthcare costs and insufficient growth of tax revenue, but it also adds as a cause an aging population. Hence, its attack on Social Security is direct, as one would expect from a group funded by Peterson. In summary, the Peterson report

“recommends that Congress and the White House follow a six-step plan: Step 1: Commit immediately to stabilize the debt at 60 percent of GDP by 2018; Step 2: Develop a specific and credible debt stabilization package in 2010; Step 3: Begin to phase in policy changes in 2012; Step 4: Review progress annually and implement an enforcement regime to stay on track; Step 5: Stabilize the debt by 2018; and Step 6: Continue to reduce the debt as a share of the economy over the longer term.”

The differences between the Peterson plan and the EPI blueprint are that EPI would move toward deficit and debt reduction more slowly, and its debt stabilization would be at higher levels (a ratio of about 80% for the medium term and 60% for the longer term, versus 60% and 40%, respectively, for the Peterson plan). According to the Peterson report, the consequences of not getting debt and deficits under control are: “An ever-growing debt would likely hurt the American standard of living by fueling inflation, forcing up interest rates, dampening wages, slowing economic growth and job creation, and shrinking the government’s ability to cut taxes, invest, or provide a safety net.”

I carefully searched the EPI report to find exactly what it is about growing debt and deficits that makes them “unsustainable” and “undesired”. There is no serious attempt made to justify the recommendation to “stabilize” and then reduce debt ratios. Indeed, in the 70-plus page document, the supposed negative impacts of growing debt ratios are discussed only briefly in three places. It boils down to this:

a) budget deficits and government debt might crowd-out private investment;

b) high deficit and debt ratios would hinder government’s ability to deal with future financial crises;

c) high debt ratios could trigger a fiscal crisis;

d) high debt service (ie paying interest on bonds) could crowd out other government spending;

e) high debt ratios could threaten confidence in government debt.

The Peterson report is much more hysterical about the possibility—nay, near certainty—of a fiscal crisis if debt ratios are not reduced. It also adds to the list above the possibility that deficits will spark inflation and devaluation of the dollar, and claims that deficits slow economic growth. But in general outline, the two analyses warn of similar dangers without providing any serious discussion of the mechanisms through which deficits and debts generate these outcomes.

Let me stick to the EPI fears. While we probably disagree about operational details, I suspect EPI agrees that government can make all payments as they come due in its own sovereign currency—that is a position to which even Ben Bernanke, Alan Greenspan, and Paul Krugman subscribe. But if that is so, I do not see how a “fiscal crisis” can be triggered. Let us say that market confidence in Treasuries is shaken. A sovereign government can offer to redeem all of them—that is, stand ready to pay off interest and principal by crediting bank accounts with US dollars. Yes, I know that the inflation hyperventilators are already screaming. But EPI did not list inflation as a possible result; it listed fiscal crisis. How can you have a fiscal crisis when you spend your own currency? EPI is silent on the matter.

The EPI report lists two types of crowding out. The first is the old and thoroughly discredited loanable funds idea: there is a fixed amount of loanable funds in markets and if government borrows, there is less available for private firms. Interest rates rise, investment falls, and growth suffers (one of the Peterson claims). There is also an ISLM version—but that is equally discredited (all modern macro has a horizontal LM curve) and too wonky for this blog. One must conclude that EPI’s macroeconomics is based on pre-Keynesian theory.

Actually, finance is not a scarce resource. (Anyone who thinks it is scarce had a Rip Van Winkle nap during the last two decades, when finance was more abundant than hot air within the Beltway.) Government deficits cannot financially crowd out investment. Yes, if we went beyond full employment of all resources, more government spending could crowd out private spending because there would be no real resources to devote to production of additional output. But it is pretty clear that EPI is not worried about real resources, since its Blueprint devotes Bullet 3 to ramping up public investment.

The second kind of crowding out listed is based on the belief that government faces a fixed budget so that if it spends more on interest it must cut spending (or raise taxes) elsewhere. This is also related to the view popularized by neoliberals Reinhart and Rogoff that low debt ratios are good because when a crisis hits there is fiscal policy space that can be used for bail-outs and stimulus packages. But that means EPI is using a circular argument: we must reduce the debt by cutting spending because the debt imposes a constraint on spending.

The reality is, as all those reading this blog know well, a sovereign government is never financially constrained in its own currency. Government spends by keystrokes. It can stroke keys to pay interest and as well stroke keys to undertake any progressive spending policies EPI proposes. And it still has “room” to stroke keys for bailouts. There is no affordability tradeoff. What matters is inflation—too much government spending drives the economy to the inflation barrier. And real resource use: a government that takes too many resources for its use (hopefully, to serve the public purpose) leaves too few for the private sector. But that requires full capacity use—otherwise at most you get bottlenecks.

Further, as all readers here know, the interest rate is a policy variable. The central bank chooses the overnight interest rate; the short maturity government bill rate tracks that closely since bills are close substitutes for bank reserves. Other rates are more complexly determined. Government bills and bonds are interest-earning alternatives to the rates paid on reserves by the central bank. Let us say that government decides it wants to spend less on interest on longer maturity bonds. Easy enough: stop issuing them. Facing a drought of longer maturity bonds, markets will bid up their prices and rates will fall. Government can stay in the short end of the market as long as it wants; indeed, it can stop issuing even bills and just pay 25 basis points on reserves (as it now does). Yes, this requires a change from current operating procedure. I won’t go through this now as NEP has provided ample analysis of operating procedures and the simple changes that would lead to an era of zero government debt (as conventionally measured, since reserves and currency are not counted).

Now, EPI might challenge me: what would my progressive 15 to 25 year government budget proposal look like? My response: I wouldn’t budget for 5 years, let alone 25. It is a silly exercise that only stokes the fires of Peterson’s hyperventilators.

The best argument against doing long-term budgeting exercises is here, a co-authored Policy Brief that was based on testimony we supplied to Congress. A quick summary is contained in my FDL piece (here). This blog is already too long to repeat the arguments. Budgeting by sovereign government does make sense, and one could even envision budgeting for particular long-lived projects for periods as long as 25 years. But it makes no sense to project total government spending, taxing, and deficits out to 15 or 25 years, let alone to infinity and beyond. And once we bring in recognition of the three sectors balances and the necessity they sum to zero, the futility of calculating budget deficits for year 2035 becomes obvious. You cannot even get a budget deficit unless the private sector wants to net save and the rest of the world wants to earn dollars by net exporting. To calculate the budget deficit in 2035 we would have to be able to project out the current account balance and the private sector balance. That is something EPI did not do—and so, the whole exercise is not only silly but seriously incoherent from the vantage point of the sectoral balances.

In conclusion: critics have wrongly implied that EPI (and perhaps RI and CAP) adopted Peterson’s hawkish approach because they were paid to do so. The similarity between the EPI and the Peterson position on sustainability of deficits and debts predates the funding. The EPI Blueprint does adopt a progressive approach to budgeting, so long as one agrees that progressives should adopt a dovish approach to budget deficits, and that it is progressive to draw up budgets for the far distant future. Personally, I reject both of those stances.

But, MMTers are in a distinct minority—we are deficit owls. As I have argued here, most progressives have lined up on the Peterson side because they adopt the deficit dove position. And that is why all progressive policies adopted since the Great Depression are now in danger.

Counterfactuals can never be proven. What if Beltway progressives had mounted a strong opposition against Peterson? What if they understood and endorsed MMT? Would Democrats have found the will to call the Republican’s bluff? Would Obama have stood up to the attacks on the New Deal? We will never know.

I conclude: progressives have unwittingly aided and abetted the deficit hawks because they do not have any strong alternative to the argument that deficit and debt trajectories are “unsustainable”.