Politicians are under huge pressure, particularly when things are going horribly wrong as they seem to be with England’s efforts to convince the Scots to spurn independence, to say something profound. They rarely become politicians because they are capable of profound thinking however, so in every nation their efforts at being thoughtful often turn out tragicomic. The vote “No” effort is so desperate that it has recruited former Prime Ministers Gordon Brown and John Major, the UK’s most unpopular, failed leaders. They have made it their mission, very late in the contest, to try to convince Scots not to recover their independence. The “No” leaders relied primarily on threats to punish the Scots should they dare to vote for independence. This turned a referendum they were almost sure to win by a wide margin into a PR disaster. Now, with the polls showing that the “No” forces could succeed in snatching defeat from what should have been a decisive victory, they are casting about desperately for some positive reason that will resonate with the average Scot to make her or him want to be a Brit. The anti-independence politicians have tried over a dozen variants of this latest strategy in the last two days (along with a switching from extortion to last minute promises of greater autonomy).

Each of us may have a favorite wackiest “reason to stay a Greater Brit” plea arising from Westminster’s desperation charge into Scotland. My favorite wackiest reason to stay a Greater Brit was offered by Brown and Major – the oddest of odd couples united against an independent Scotland. Brown and Major say the Scots should identify primarily with Great Britain rather than Scotland because they should feel nostalgic about “the [British] army” and particularly its tragic losses in World War I (the oxymoronic “Great War”).

Brown, in a column in the New York Times designed to be read by an overwhelmingly American audience, emphasized that Great Britain was not held together by ethnicity. The English (mostly descendants of the Germanic Angles and Saxons) have always considered their Celtic non-cousins to be inferior – mocking the Irish as subhuman even as we died of starvation by the hundreds of thousands in their first colony (Ireland). Brown then admitted that the peoples of Great Britain were not united by ideas. He argued that they were traditionally united by their shared institutions.

“Britain has never been united by ethnicity. We are four nations in one state. And, always pragmatic, we have never shouted from the rooftops about the shared ideas that bind us together in the manner of America (land of liberty and opportunity) or France (liberté, égalité, fraternité).

Instead, Britain has its institutions — from the monarchy and the army to the House of Commons and the BBC — none of which now appear able to generate enough Scottish pride in the union to secure a decisive “no” vote.”

First, it is Americans that are most famously “pragmatists.” The “monarchy?” Seriously? Brown needs to recall that Thomas Paine’s pragmatism expressed in “Common Sense” swept the 13 colonies because his description of British royalty as a pack of pretentious, overdressed thieves so obviously reflected reality. Disposing of royalty was one of the great virtues of independence – we no longer had to support and kowtow to a passel of pseudo-royal parasites. The BBC, well, we like a lot their shows too, but we never dreamed of renouncing our independence to be able to watch “Upstairs, Downstairs.”

The British “army?” Someone needs to remind Brown that we repeatedly fought the British army (and navy) because we wanted to be independent of the Brits (including the “monarchy” and “the House of Commons”). The UK embassy in the U.S. recently thought it would be a fun idea to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Brits torching the White House in 2014. The Scots, shamefully, fought against us in their role as members of the British army. An enormous amount of the fighting the Scots did for the British army was killing people fighting desperately to achieve their independence from England. Americans largely rooted for the folks that the Scots were killing. The fact that England found the Scots’ military skill and bravery to be so useful to their colonial depredations should not “generate … Scottish pride.” The fact that Brown, a former Labor PM, thinks that that is should “generate … Scottish pride” shows how warped Scots can become when they serve foreign masters committing some of the world’s great crimes.

John Major’s Nostalgia for the “Great War”

It was perhaps to avoid Brown’s historical embarrassment that led another spectacularly unpopular failed former PM, John Major, modified Brown’s claim that the British army was a “shared institution” that should “generate … Scottish pride” by focusing on the Great War, a (somewhat) non-colonial war. (It was, of course, a colonial war in the sense that the Brits used colonial troops who suffered massive losses. The English tried to tell these colonial soldiers that their service in the British army should “generate [fill in the name of the people of the colony providing the troops here] pride” – but that message was usually derisively rejected.

“John Major, a Conservative former prime minister, added his voice Wednesday in a BBC radio interview. ‘I am desperately concerned at what is happening’ he said. ‘We would be immensely weaker as a nation in every respect — morally, politically, in every material aspect — if Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom were to part company.’

‘This year is the 100th anniversary of the First World War. As we honor the people who fought together then, would it not be extraordinary if the S.N.P. broke up the most successful union and partnership in all history in any part of the world?’ he said, using the initials of Mr. Salmond’s Scottish National Party.”

Major’s comments bring to mind Winston Churchill’s romantic (and “pragmatic” only in the most cynical usage of that word) endorsement of the glory of dying for one’s nation in his obituary for Rupert Brooke. Brooke was a poet who had virtually no experience as a soldier. He died of sepsis from a mosquito bite (he was weakened by dysentery and heat stroke) on a troop ship on the way to the charnel house that was Gallipoli. Churchill, of course, was the architect of that disaster that was Gallipoli. A poet who fought in the Great War, Wilfred Owen, denounced the claim that it was sweet to die for one’s Nation as “the old Lie.” Gallipoli ruined Churchill’s reputation and, as its horrors emerged, Brooke’s reputation as a war poet who never knew war. Brooke, Churchill, and Major all seek to make the monstrosity of mass murder and maiming into an aspect of patriotic “holiness” that leaves with every corpse blown into shreds by a 155 mm shell in France “an English heaven” that Brooke claimed formed England’s “heritage.”

Rupert Brooke: Obituary

Rupert Brooke is dead. A telegram from the Admiral at Lemnos tells us that this life has closed at the moment when it seemed to have reached its springtime. A voice had become audible, a note had been struck, more true, more thrilling, more able to do justice to the nobility of our youth in arms engaged in this present war, than any other more able to express their thoughts of self-surrender, and with a power to carry comfort to those who watch them so intently from afar. The voice has been swiftly stilled. Only the echoes and the memory remain; but they will linger.

During the last few months of his life, months of preparation in gallant comradeship and open air, the poet-soldier told with all the simple force of genius the sorrow of youth about to die, and the sure triumphant consolations of a sincere and valiant spirit. He expected to die: he was willing to die for the dear England whose beauty and majesty he knew: and he advanced towards the brink in perfect serenity, with absolute conviction of the rightness of his country’s cause and a heart devoid of hate for fellow-men.

The thoughts to which he gave expression in the very few incomparable war sonnets which he has left behind will be shared by many thousands of young men moving resolutely and blithely forward in this, the hardest, the cruelest, and the least-rewarded of all the wars that men have fought. They are a whole history and revelation of Rupert Brooke himself. Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, ruled by high undoubting purpose, he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in the days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable, and the most precious is that which is most freely proffered.

Winston Churchill, obituary note in The Times (26 April 1915).

The Great War produced immense amounts of courage and sacrifice through the mass slaughter of human beings, animals, and wealth. The concluding section of this article contains extensive excerpts from a book (Those Who Fell In The Great War) available on line. I recommend it to anyone wishing to learn about the Great War because of its mix of the small and large. It is a project of the government of Scotland that honors Scotland’s soldiers who served in the Great War. The book is in no way anti-British. It is not a screed about war or those who fight wars. I have not provided any editorial comments.

The leadership of Field Marshall Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force in France, is a subject of intense dispute among military historians. Haig receives mixed reviews in the book. Readers should know that Haig was a Scot. The Great War was not a case of cowardly Brits sending the Scots to die in their stead.

Major’s claim about the war would not be logical even if nostalgia was a proper reaction to the Great War. Soldiers from all over the Commonwealth died in the Great War fighting alongside the Brits, the Scots, the Welsh, and the Irish. The French, Americans, Russians, Belgians, and Italians died in the same cause. None of this suggests that any of these people should remain in a “union” with the English. American troops made an significant contribution to the Allies winning World War I, but none of us every thought this meant we should renounce our independence from the UK.

The book about the Scots who died in the Great War makes clear that the war prompted enormous enthusiasm among all classes of Scots. The elites and the working class rushed to enlist.

The excerpts make clear the devastating effects of the Great War on Scots and Scotland and hints at the changes in public attitudes that began as word of the savagery and the nature and scope of the casualties became known by the public. As Churchill’s obituary note indicates, the war leaders were eager to “carry comfort to those who watch” their loved ones go off to war. The book notes that huge hospitals were built on rail lines so that trains could unload thousands of men suffering ghastly injuries inside the hospital walls in order to ensure that the public would not see the true face of the Great War.

The book contains Owen’s famous poem denouncing “the old Lie” that it is “sweet” (glorious) to die for one’s Nation. It also explains that a special zinc commemorative disc was minted by the UK for the survivors of every soldier killed-in-action and how many tons of zinc were required.

THE SCOTTISH OFFICE

THOSE WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR

Compiled by Neil MacLennan

[The Battle of the Somme]

16TH ROYAL SCOTS (McRAE’S OWN)

The Battalion was raised and commanded by Lt Col Sir George McCrae, head of the Local Government Board for Scotland. The Battalion comprised 1,347 officers and men who in civilian life were students, lawyers, doctors, labourers, artists and clerks. The Battalion also included 11 professional footballers from Heart of Midlothian Football Club, something that no doubt inspired others to sign up when the Battalion was formed in 1914. With the Battalion formed, initial training took place in Yorkshire and on Salisbury Plain before embarking at Southampton and landing in France in January 1916.

John Jolly

[Jolly] went over the top with his Battalion at 0730 on 1 July 1916, the infamous First Day of the Somme. A contemporary report reads as follows:

“Briggs and Brown fell just in front of the entrance to Wood Alley, a communication trench which led back to the German third line. Captain Peter Ross, the last remaining officer in [the] company, arrived here at about 8.15. He gathered the remnants of his command in order to rush a machine gun further down the trench. As he moved forward, the gunner shot him in the stomach almost cutting him in two. Sgt John Jolly, a civil servant from Edinburgh, now took the lead. He was shot through the head within seconds and was killed instantly. Ross meanwhile, was still alive and in unimaginable pain. He begged someone to finish him off. In the end, it came down to an order. Two of his own men reluctantly obliged, one of whom would kill himself 20 years later. Ross, a school teacher and author from Edinburgh, was 39 years old.”

From McRae’s Battalion, the story of 16th Royal Scots by Jack Alexander

Another report states that many in the 16th Battalion were “scythed like corn” in front of the German machine guns. With 20,000 dead, the day ranks as the bloodiest in the history of the British Army. The 15th and 16th Royal Scots (as part of 101 Brigade) were in action from 0730 in the area of La Boiselle. They suffered 80% and 50% casualties respectively.

John Jolly’s body was never found and his remains will either be in an unmarked grave or lie somewhere in the vicinity of Contalmaison, where 228 of his comrades were killed that day. His name is inscribed on the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval.

Francis Howard Lindsay had been an Examiner with the Scotch Education Department since 1899, earning a First Division salary of £400 per annum. He was a Captain and Temporary Major in The 14th Battalion London Scottish along with his brother, James, who survived the war after being wounded in 1917.

Another brother, Michael, was killed some years previously during the Boer War. Like many in the First Division, Francis had graduated from Cambridge as a Bachelor of Arts. He was 40 years old when, along with John Jolly and Harold Double, he was killed on the First Day of the Somme. He was survived by his wife, Helen Margaret MacDougall, who lived in South Kensington with their two children John (5) and Katherine (six months).

[The Battle of Passchendaele]

Cyril William Gibson was a Gunner with ‘B’ Battery, 47 Brigade the Royal Field Artillery. He was 21 when he was killed on 5 December 1917 by a defective shell which exploded while being handled. He is buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery near Ypres which, with nearly 12,000 graves, is the largest cemetery maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The area was the scene of heavy fighting towards the end of 1917 as part of the advance on Passchendaele, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, a battle that became synonymous with the misery of fighting in thick mud. Such was the carnage that nearly two-thirds of the burials at Tyne Cot are unidentified.

His experience in the OTC made William [Hutchinson] well placed to join the rush to enlist in August 1914, and he duly volunteered to join the Special Reserve. Around 600 Edinburgh University students and graduates were given immediate commissions, and William became a 2nd Lieutenant in The King’s (The Liverpool Regiment). He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1915 and Captain in 1916.

William had just been appointed to join the staff of his Brigade and was due to join them when he finished the period in the trenches in which he was killed. Having survived nearly two years of fighting when the average life expectancy for a commissioned officer in the infantry was six weeks, William’s luck had finally run out. Had he made it to the Brigade Staff, his chances of surviving the war would have markedly increased. One of four brothers, William was the second son of Mr and Mrs William Innes Hutchison of Sefton Park, Liverpool. His older brother, Captain Innes Owen Hutchison, served with The Black Watch and was killed in Mesopotamia four months earlier. Innes was 24 years old, has no known grave, and is commemorated on the Basra Memorial near where British troops were still fighting 90 years later.

Most of the battle took place on largely reclaimed marshland which was swampy even without rain. The heavy preparatory bombardment in which Cyril Gibson and the Royal Field Artillery would have participated tore up the surface of the land which, following heavy rain, turned the area into a sea of deep ‘liquid mud’. It was into this mud that an unknown number of soldiers, weighed down with their equipment, sunk without trace.

After three months of fierce fighting the battle ended, with the Allies sustaining almost half-a- million casualties. They had captured a mere five miles of new front at a cost of 140,000 lives, a ratio of roughly two inches gained per dead soldier.

[Field Marshall Haig, Commander-in-Chief, British Expeditionary Force]

The enormous casualty levels — coupled with the horrendous conditions in which the battle was fought — damaged Field-Marshal Douglas Haig’s reputation as a battle strategist. Haig’s statue now stands opposite Dover House, where Cyril Gibson used to work. Haig is buried at Dryburgh Abbey in the Scottish Borders beneath a headstone similar to those that commemorate the men who died under his command.

The last resting place of Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, Dryburgh Abbey

[WKB: Haig’s tombstone bears his first regiment’s crest: Douglas Haig was commissioned into the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars in 1885, a regiment raised in Scotland.]

[The Loos Offensive]

The Loos offensive began on 25 September 1915 following a four–day artillery bombardment in which 250,000 shells were fired. It was called off in failure three days later. Presided over by Field Marshall Haig, the British committed six divisions to the attack. Haig was persuaded to launch the Loos offensive, despite misgivings. He was concerned at both a shortage in shells and the fatigued state of his troops. He was further concerned given the nature of the flat terrain that would need to be crossed, but which offered no cover.

Set against these concerns however, was the fact that the British enjoyed massive numerical supremacy against the German opposition of up to seven to one in places. Once the initial bombardment had concluded, the battle plan called for the release of 140 tons of chlorine gas from the British front line. The quantity of gas used was designed to overcome the primitive German gas masks in use at the time, but this aspect of the attack did not go to plan. In places, the wind blew the gas back into the British trenches and resulted in over 2,600 casualties.

During the battle the British suffered 50,000 casualties including Hugh MacKenzie. German casualties were estimated at approximately half the British number.

It was during this battle that Rudyard Kipling’s son, John, was lost believed killed. The fact that he was listed as missing sparked a campaign by his parents to locate his body and give him a proper burial. Despite their best efforts he was never found. The whereabouts of John and his comrades Hugh MacKenzie and Alexander Fraser (qv) remain unknown to this day.

Rudyard Kipling provided the foreword to the Edinburgh University Roll of Honour, which also features William Hutchison and Bertram Matthews (qv).

[Gallipoli]

Ronald [William Sanders] was a Private with 4th Battalion The Royal Scots (The Queen’s Edinburgh Rifles). He sailed from Liverpool on 24 May 1915, and travelled via Egypt to the Gallipoli peninsula where the Battalion landed on 14 June 1915.

By this time, around 6,000 Commonwealth troops had been killed and a further 15,000 wounded out of an original force of 70,000.

The medical facilities were completely overwhelmed and one British soldier wrote that Gallipoli “looked like a midden and smelt like an open cemetery”.

Gallipoli was one of the major disasters of the war, and was a factor which caused the architect, Winston Churchill, to retreat in to the political wilderness for the best part of 20 years. The idea was simple in that by opening a second front the Germans would be forced to split their army. However, poor preparation, an underestimation of the ability of the Turkish fighting forces and a lack of political direction all conspired to cause the operation to fail.

Ironically, the one major success in the whole campaign was the withdrawal, which was done virtually without loss. However, as Churchill was to comment after another valiant withdrawal at Dunkirk some 25 years later, “Wars are not won by evacuations”.

Ronald’s Battalion returned to Egypt on 8 January 1916, but his body was never found and lies somewhere on the peninsula to this day. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial along with more than 21,000 comrades.43

Kichener’s New Army

11th Royal Scots were part of Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ which was formed at the outbreak of war. The New Army was made up of volunteers (as opposed to Regular units) which Kitchener (as Secretary for War) formed because he did not agree with the popular belief that “it would all over by Christmas”. Kitchener was convinced that the war would be long and brutal and that, if it was timed properly, the arrival of a new well-trained army would deliver a decisive blow. As things turned out, it did no such thing.

Instead, thousands of inexperienced troops were poured into the grinding machine that was the Western Front, organised around geographical areas or workplaces like the Civil Service Rifles.

The Civil Service Rifles was known as a ‘pals Battalion’, so-called because in order to aid enlistment and build cohesion recruits were called up alongside people they knew from their civilian lives. The downside was that when the Battalion went into action, the town or organisation with which the men were associated was dealt a heavy blow, having to cope with a large number of casualties over a short period of time. Clearly Whitehall was a prime recruiting ground for the Civil Service Rifles, and so it was to this unit that Robert Buckingham enlisted, along with Dover House colleagues Frederick Grist and Charles Henry (qv). By the end of the war 1,240 men of the Civil Service Rifles were dead.

[Arras]

The Arras Memorial commemorates almost 35,000 men who died in the Arras sector between spring 1916 and August 1918 (the ‘Advance to Victory’). The men listed on the memorial have no known grave. One of the most conspicuous events of this period included the Arras offensive of April-May 1917, in which Henry [Stuart Adams] lost his life. The offensive started on 9 April and was an attempt to break the stalemate and push the war into the open ground behind the trenches, so that the Allies’ superiority in numbers could be better exploited. Allied troops made many advances, but they failed to achieve the breakthrough they has sought.

The sector reverted to stalemate when the battle ended on 16 May with 160,000 casualties.

Scottish Military Hospitals

The buildings at Bangour can still be seen near the village of Dechmont in West Lothian, including the relocated station and the remains of the track bed used by the hospital trains, which took the wounded straight in to the grounds. Bangour was built as an asylum in the early part of the 19th century, and was taken over in 1915 by the War Office as a military hospital.

The number of staff and beds increased dramatically to cater for the influx of wounded soldiers who began to arrive from June of that year. Leith was a key port for the hospital ships, and by 1918 the hospital had reached a record capacity of 3,000 patients crammed into wards, huts and specially-erected marquees in the grounds. The hospital trains took the wounded straight into the grounds, which avoided any risk to public morale had the thousands of casualties been unloaded at a civilian station.

Dulce et Decorum est Pro Patria Mori features in the work of Wilfred Owen. Roughly translated it means “it is a wonderful and great honour to fight and die for your country”. Owen, having described the death throes of a comrade coughing up blood from his froth-corrupted lungs following a gas attack, goes on to describe this as “the old Lie”.

[The Third Battle of the Aisne]

Oliver Bruce worked for the Board from 1914 until he was called up in 1917. 2nd Lieutenant Bruce served with 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade. He was the son of Oliver and Jessie Bruce of Alder Bank Place, Edinburgh, and died on 9 June 1918 aged 21. He lies in Terlincthun Cemetery on the northern outskirts of Boulogne. 2nd Battalion was involved in the Third Battle of the Aisne, which raged from 27 May until 6 June and was the final attempt by the German Army to win the war before the arrival of US forces in France in numbers.

The line facing the Germans was held by four British divisions of IX Corps which, somewhat ironically, had been sent from Flanders in early May in order to recuperate. The exhausted troops were unable to contain an onslaught launched with a bombardment by 4,000 guns and a gas attack. They suffered 29,000 casualties and IX Corps was virtually wiped out.

BATTLE OF AUBERS

Prior to the Battle of Loos, The Black Watch had been in the area of Le Touret for the Battle of Aubers. This battle had been planned to press the Germans at a time when they were heavily committed on the Eastern Front. On 9 May at 3.57pm, while the German trenches were being subjected to heavy bombardment, the leading companies of The 1st Black Watch went over the top despite their support being late to arrive. Mindful of the risk of being out in the open, they were ordered to move at the double across No Man’s Land, but to no avail. Most were either killed or captured. Alexander Fraser was probably a replacement for one of more than 11,000 British casualties on that day, large numbers of whom were cut down by machine-gun fire within yards of their own trench. Mile for mile, Division for Division, the losses suffered by The Black Watch on 9 May were one of the highest of the entire war.

[The Battle of Cambrai]

Alexander [Hunter] was 22 years old when he died on 20 November 1917. His unit was fighting as part of 154th Brigade with the 51st Highland Division. On 20 November the Division was attacking in the area of Flesquieres on the opening of the Battle of Cambrai. This was the battle where tanks were first deployed in numbers, helping to break deeply and quickly into apparently impregnable defences with few casualties.

This result was widely regarded as being a great and spectacular achievement, but two months later a court of inquiry was convened after the hard-fought gains were lost to a German counter attack. The initial success which cost Alexander his life had been short lived, and there was bitter disappointment at the net result. Alexander has no known grave and is commemorated on the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval.

[The Village of Buzancy]

By July 1918, Private [D.] Moodie was fighting as part of 15th Scottish Division which, on 27 July, was holding a two-mile stretch of front facing the village of Buzancy. On the 28th they attacked across ground that was devoid of cover, and although they took the Château of Buzancy quite quickly, they found the village more troublesome.

Eventually, outflanked and outnumbered, the Highlanders were driven first from the village, then from the château. They came clear of artillery fire only to find enemy machine gunners to the rear of them. These they bombed with hand-grenades taken from a German dump in the château grounds and, after having sent back as prisoners six officers and over two hundred others ranks, they regained their starting line soon after 6pm. The 15th Division, which had been in most of the heavy encounters of the war since Loos in September 1915, regarded the action on this day as “the severest and most gruelling” of them all. Private Moodie was a casualty and died of his wounds two days later.

[The Scots and Canadians at Arras]

George [Butler Walker] is buried at Nine Elms Cemetery, six kilometres from Arras. The cemetery includes a large number of soldiers who fell on the same day as George, including a row of 80 graves belonging to the men of a Canadian Infantry Battalion who were all cut down as soon as they stepped out their trench.

The Dead Man’s Penny

Once the carnage was over, the nation was in shock. The scale of the losses were enormous, with hardly a family across the land left unaffected.

This was a difficult time for the Government given events in the east where the Russian Revolution had taken hold, compounded by the fact that Britain was essentially broke.

There was a clear and pressing need to recognise the sacrifice of the fallen, but care had to be taken to do this in a way that was respectful and not seen as patronising. While there was undoubtedly a genuine desire in many quarters to recognise the sacrifice of many, there was also a desire to address well-founded concerns that the prevailing sense of disenchantment around the scale of the carnage, and the absence of the ‘land fit for heroes’, could develop into something more serious.

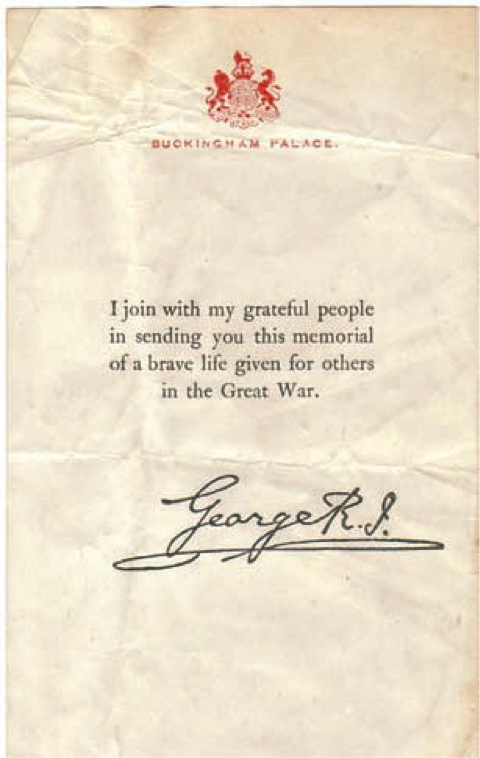

A memorial plaque was issued to the next-of-kin of all British and Empire service personnel killed as a result of the war. The plaques were made of bronze, and commonly referred to as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ because of the similarity in appearance to the somewhat smaller penny coin of the day. 1,355,000 plaques were issued using 450 tonnes of bronze, along with a facsimile letter from the King and a commemorative scroll.

However the Dead Man’s Penny was received then, holding one today you cannot escape the sense of scant consolation for the loved one who would never be coming home.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Wilfred Owen

8 October 1917

[WKB: The Latin translates roughly as “it is glorious to die for one’s Nation.” Owen was killed in action one week before Armistice Day.]

Pingback: Links 9/12/14 | naked capitalism