By Eric Tymoigne

Previous posts studied the balance sheet of the Fed, definitions and their relation to the balance sheet of the fed, and monetary-policy implementation. This post answers some FAQs about monetary policy and central banking. Each of them can be read independently.

Q1: Does the Fed target/control/set the quantity of reserves and the quantity of money?

The Fed does not set the quantity of reserves and does not control the money supply (M1). It sets the cost of reserves; that is it.

In terms of reserves, the Fed was created to provide an “elastic currency,” i.e. to provide monetary base according to the needs of the economic system in normal and panic times. It would be against this purpose to implement monetary policy by unilaterally setting the monetary base without any regards for the daily needs of the economy system.

In terms of the money supply, the Fed has no direct influence. Even Federal Reserve notes (FRNs) are supplied through private banks, and banks supply only if customers ask for cash. The Fed does not force feed FRNs to the public, i.e. FRNs cannot be “helicopter dropped” via monetary policy. If the Fed did this, not only would it operate against the Federal Reserve Act, but also it would lead people to take the FRNs, bring them to banks, banks would have more reserves, FFR would fall, Fed would remove excess reserves to bring FFR back up—back to square one.

The Fed may have an indirect influence on the money supply through changes in its FFR target because changes in the cost of credit may change the willingness of economic units to go into debt, but the link is tenuous (see Q10).

Q2: Did the Volcker experiment not show that targeting reserves is possible?

In the 1970s, the Monetarist school of thought gained some influence in policy circles. Monetarists argued that there is a close relation between the quantity of reserves and the money supply, and that the role of a central bank is to control the quantity of reserves in order to influence the money supply and ultimately inflation (see the quantity theory of money in Post 11). The Fed, under the leadership of Paul Volcker, tried to implement a monetary-policy procedure that aimed at more closely targeting reserves and monetary aggregates, with the hope of taming a double-digit inflation rate.

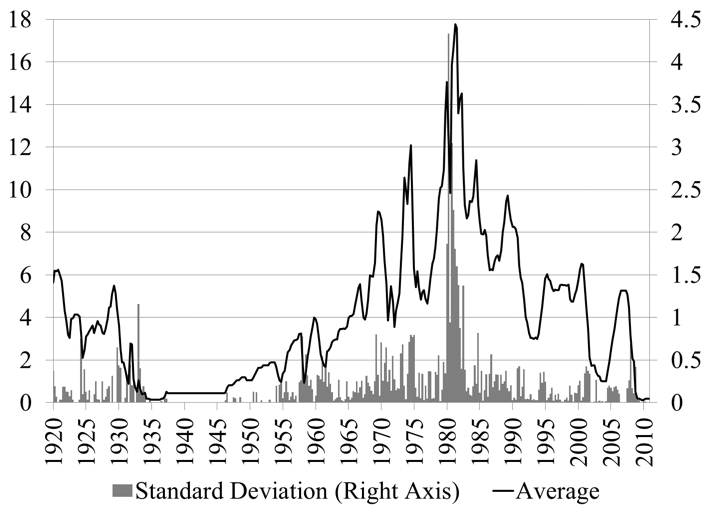

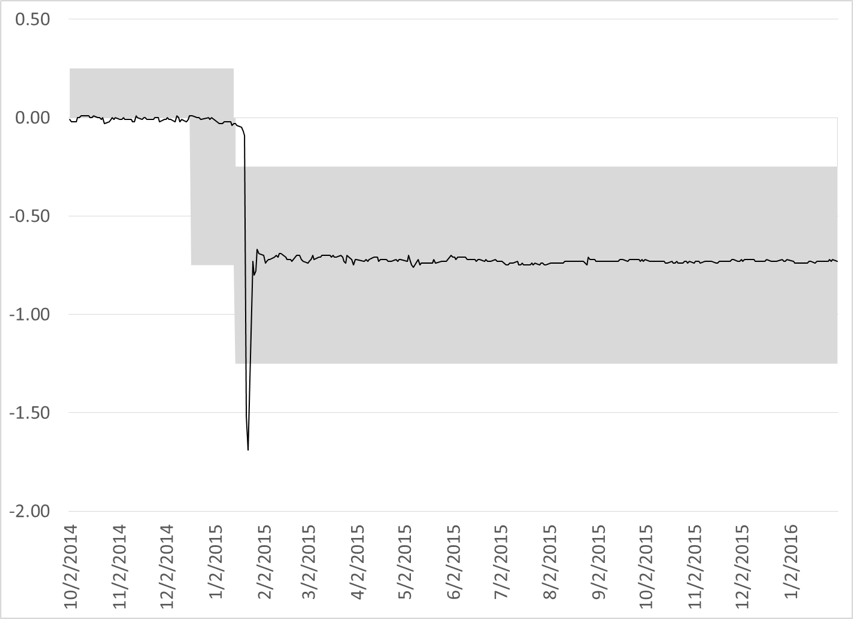

Practically, the Fed changed interest-rate targeting from a narrow range to a wide range, which rose the level and volatility of the FFR dramatically (Figure 1). The Fed did not allow the FFR to move freely as a targeting of total reserves implies.

Figure 1. FFR, Monthly Average and Standard Deviation

Source: Federal Reserve Board, NY Federal Reserve Bank

There is an academic debate about how truly “Monetarist” the Volcker experiment was, and this debate is reflected in the FOMC discussions of the time

ROOS. Well, if the level of borrowing comes in higher than we would anticipate, [can’t] you reduce the level of the nonborrowed reserves path accordingly? Can’t you adjust your open market operations for the unexpected bulge in borrowing or the unexpectedly low borrowing if you ignore the effect on the fed funds market? Can’t you just supply or withdraw reserves to compensate for what has happened?

[…]

CHAIRMAN VOLCKER. The Desk can’t [adjust] in the short run. It’s fixed. In a sense they could do it over time if people are borrowing more, as they may be now. They seem to be borrowing more than we would expect, given the differential from the discount rate. But in any particular week it is fixed.

ROOS. Do we have to supply the reserves?

CHAIRMAN VOLCKER. We have to supply the reserves.

ROOS. [Why] do we have to supply the reserves? If we did not supply those reserves, we’d force the commercial banks to borrow or to buy fed funds, which would move the fed funds rate up. (FOMC meeting, September 1980, page 6)

Mr. Roos was deeply dissatisfied with the Fed still using a FFR target, albeit in the form of a wide range. While the Fed had a total-reserve growth target related to the 3-month growth rate of M1, if banks needed more than what was targeted, the Fed would supply extra reserves in order to relieve pressures on the FFR. Roos argued against this lenient reserve targeting and was for a total abandonment of any FFR targeting and a strict targeting of total reserves. Here he is in 1981:

I think there’s a very basic contradiction in trying to control interest rates explicitly or implicitly and achieving our monetary target objectives. And I would express myself as favoring the total elimination of any specification regarding interest rates. (Roos, FOMC meeting, February 1981, page 54)

Most Federal Open Market Committee members were against that position on the ground that the role of the Fed is precisely to promote an elastic monetary base. The Fed was not created to dictate what the quantity of reserves ought to be but to eliminate liquidity problems through smooth interbank debt clearing at par, lender of last resort, and interest-rate targeting. In addition, banks mostly hold reserves because they are required to, so if the Fed does not supply enough reserves to meet the requirements then banks will break the law.

The experiment was a monetary-policy failure. The Fed was never able to reach its reserve or money targets and the experiment contributed to massive financial instability and a double-dip recession. One may even doubt that it contributed significantly to the fall in long-term inflation, which had more to do with the downward trend in oil prices, oil-saving policies and greater international labor competition:

May I remind you that we shouldn’t take too much credit for the price easing? I never thought we were totally at fault for the price increases that we suffered from OPEC and food; and I don’t think the fact that OPEC and food have calmed down has a great deal to do with monetary policy per se, except in the very long run. (Teeters, FOMC meeting, July 1981, page 46)

The Volcker experiment was, however, a public-relation success. Most FOMC members knew that reserve targeting was not possible but, it allowed them to claim that they were not responsible for the high interest rates of the period:

I do think that the monetary aggregates provided a very good political shelter for us to do the things we probably couldn’t have done otherwise. (Teeters, FOMC meeting, February 1983, page 26)

I think the important argument, and really the reason why we went to this procedure, was basically a political one. We were afraid that we could not move the federal funds rate as much as we really felt we ought to, unless we obfuscated in some way: We’re not really moving the federal funds rate, we’re targeting reserves and the markets have driven the funds rate up. That may have had some validity at the time, and I had some sympathy for it. But as time goes on, I’ve become more and more concerned about a procedure that really involves trying to fool the public and the Congress and the markets, and at times fooling ourselves in the process. (Black, FOMC meeting, March 1988, page 12)

Of course the high and volatile FFR was precisely the result of the change in monetary-policy procedures. If needed, some FOMC members were willing to do the same thing in the future:

Well, I have only a little to add to all of this. I think Tom Melzer is probably right: We’re going to need to shift the focus to some measure or measures of the money supply as we proceed here if we can, both for substantive reasons and also because that has some political advantages as well, as we go forward. (Stern, FOMC meeting, December 1989, page 50)

Q3: Is targeting the FFR inflationary?

With the failure of the Volcker experiment, the FOMC entered a period of operational uncertainty until the mid-1990s. The Fed was back on a tight FFR target procedure (there was still a wide range until 1991 but the Fed targeted the middle of the range) and this was deeply unsatisfactory to FOMC members.

We’ve advanced from pragmatic monetarism to full-blown eclecticism. (Corrigan, FOMC meeting, October 1985, page 33)

No, I would say that we have a specific operational problem that we have to find a way of resolving. Just to be locked in on the federal funds rate is to me simplistic monetary policy: it doesn’t work. (Greenspan, FOMC meeting, October 1990, pages 55–56)

In a world where we do not have monetary aggregates to guide us as to the thrust of monetary policy actions, we are kind of groping around just trying to characterize where the stance is. (Jordan, FOMC meeting, March 1994, page 49)

The Fed was unwilling to disclose that it was targeting the FFR, and continued to announce targeted growth ranges for monetary aggregates even though it did not use them for policy purposes.

[In response] to talk that says we can significantly influence this – or as the phraseology goes that if we lower rates, we will move M2 up into the range – I say “garbage.” Having said all of that, I then ask myself: ‘What should we be doing?’ Well, we have a statute out there. If we didn’t have the statute, I would argue that we ought to forget the whole thing. If it doesn’t have any policy purpose, why are we doing it? By law [we have] to make such forecasts. And if we are to do so, I suggest that we do them in a context which does us the least harm, if I may put it that way. (Greenspan, FOMC meeting, February 1993, page 39)

We do not, in fact, discuss monetary policy in terms of the Ms between Humphrey-Hawkins meetings. Don Kohn dutifully mentions them because he thinks he ought to, but that is not the way we think about monetary policy. (Rivlin, FOMC meeting, February 1998, page 91)

To announce to the general public that the FOMC was targeting the FFR would be going against all the Monetarist principles (reserve targeting, money multiplier theory, quantity theory of money). By targeting an interest rate, and so having an elastic supply of reserve (horizontal supply at a given FFRT), it seemed to indicate that the Fed was no longer willing to control inflation. FOMC members themselves believed that was the case:

Many analysts, both inside and outside the Fed, argued that using the Federal funds rate as the operational target had encouraged repeated over-shooting of the monetary objectives. (Meulendyke 1998 49)

Talking about the FFR target became a taboo and “the Committee deliberately avoided explicit announced federal funds targets and explicit narrow ranges for movements in the funds rate” (Kohn, FOMC Transcripts, March 1991, page 1):

I must say I’m still quite reluctant to cave in, if you will, on this question that we can do nothing but target the federal funds rate. (Greenspan, FOMC transcripts, March 1991, page 2)

As a practical matter we are on a fed funds targeting regime now. We have chosen not to say that to the world. I think it’s bad public relations, basically, to say that that is what we are doing, and I think it’s right not to; but internally we all recognize that that’s what we are doing. (Melzer, FOMC transcripts, March 1991, page 4)

We will see later why the entire Monetarist logic is flawed. Monetary policy is always about providing an elastic supply at a given interest rate. There is nothing intrinsically inflationary about this. Having an “elastic currency” usually just means supplying whatever amount of reserves banks want, and usually banks do not want much.

While all this was very well understood by many economists long before Volcker’s experiment (see for example Kaldor), it took FOMC members until the mid-1990s to get comfortable with FFR targeting.

Q4: What are other tools at the disposition of the Fed?

Monetary policy is always about setting at least one interest rate. While today the Fed operates mostly through the fed funds market, it has other tools at its disposition to help influence interest rates.

One is the (re)discount rate, the rate at which banks can obtain borrowed reserves. This interest rate is now higher than the FFR target but from the mid-1960s until 2003 the discount rate was usually below the FFR target. The Fed decided to put the discount rate above the FFR target to put a ceiling on the FFR and so limit upward volatility in FFR.

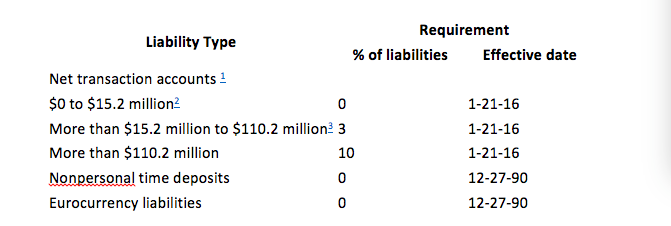

Reserve requirement ratios can also help target the FFR. These ratios state how much total reserves banks must keep on their balance sheet in proportion of the bank account they issued. This is what the ratios look like today in the US

If a bank issued less than $15.2 of checking accounts it does not have to have any reserves, 3% between 15.2 to $110.2 million worth of outstanding checking accounts, 10% beyond that.

While these ratios are often discussed in relation to the ability of banks to create checking accounts, their actual purpose is once again to help target the FFR. By raising reserve requirement ratios, the demand for reserves becomes more predictable given that a greater proportion of the reserves available must be held by banks. With a more stable demand for reserves comes less volatility in FFR.

Q5: What is the link between QE and asset prices?

The link cannot be one where banks have excess reserves that they use to buy assets in the secondary market. Post 2 explains that banks cannot do this as a whole. They could buy from one another, but if they all have reserves they want to get rid of, this is not possible because no bank wants to sell assets for reserves.

The link goes through the following channels:

- The Fed buys large amounts of securities from banks which raises their prices and so lowers their yields.

- As yields on these securities fall, economic units seek assets that provide higher yields. They will look for assets with large expected capital gains, especially so knowing that others are experiencing the same problems and are “searching for yield.” They will continue to buy these securities, which will raise their prices, until all rates of return are equalized once adjusted for risks.

Financial companies have to do the second step because they try to reach the target rates of return that they promised to their stakeholders. Pensioners expect a substantial rate of return from their pension funds, wealthy individuals expect a substantial rate of return from hedge funds, mutual funds shareholders wants a substantial rate of return…and they all check every quarter if financial companies stay on course to meet the promised target. Long-term treasuries used to provide a safe and simple way to meet this promise, no longer so.

Bill Gross (a well-known portfolio manager who specializes in bond trading) brought the point forward very clearly. He hopes that the Fed will raise the FFR to make it easier to reach targeted rates of return. He notes that low FFR prevents savers to earn enough to pay for healthcare, retirement and other costs because returns on financial assets are so low compared to the expected 7-8%. If the Fed does not help by raising the FFR, financial-market participants will take large risks on their asset side (speculative, high credit risk, and structured securities) and liability side (high leverage) to try to reach their targeted rate of return.

There is a broad problem though. In an economy in which the growth of standard of living is low, why should anyone expect that demanding 7-8% be sustainable? Those can only be achieved through capital gains and leverage and the combination of these two is highly toxic (see Post 9 and Post 14). Instead of the Fed raising its FFR, it should be the rentiers who should reduce their expectations of rate of return. An economy that grows at 2% per year cannot sustainably provide a real rates of return higher than 2% even that is a stretch. Other means must be used to meet the challenge of an aging economy than increasing the financialization of the economy.

Q6: How and when will the level of reserves go back to pre-crisis level? The “Normalization” Policy

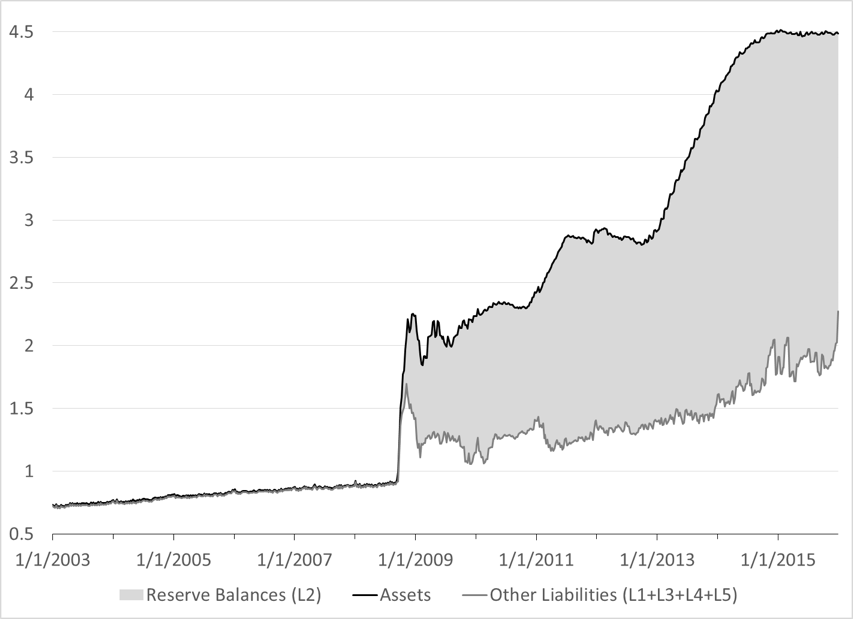

Normalization policy means the willingness of the Fed to do two things: 1-to raise the FFR to a more normal level 2- to reduce the size of its balance sheet in order to return the proportion of excess reserves to pre-crisis value. Post 4 shows how this would be done for the FFR. Regarding reserve balances, a Post 3 shows that their dollar amount is determined as follows:

L2 = Assets of the Fed – (L1 + L3 + L4 + L5)

Most of L2 is now composed of excess reserves, which is unusual. A graphical representation of this balance-sheet identity is Figure 2.

Figure 2. Balance Sheet of the Fed and Reserve Balances

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Series H.4.1)

The implication of this balance-sheet identity is that reserves balances will fall either when assets of the Fed decline given other liabilities, or when the other liabilities of the Fed rise given assets. Let us look at each case in turn.

Given other liabilities than reserves balances, reserves will not go back down until the following happens to the securities held by the Fed:

- Securities ISSUED BY NON-FED-ACCCOUNT HOLDERS mature (let’s call them “private securities” to simplify)

- The Fed decides to sell some securities to banks.

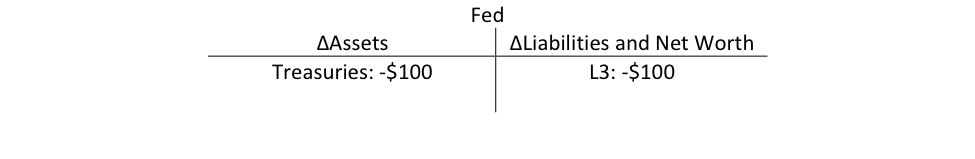

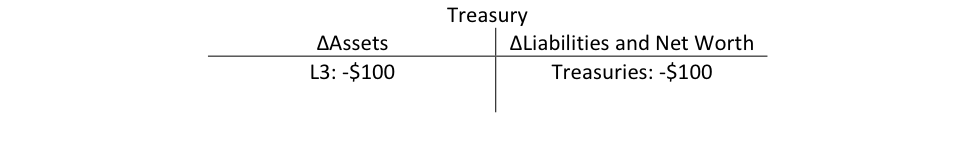

If the Fed let treasuries mature the account of the Treasury (L3), not reserve balances, are debited:

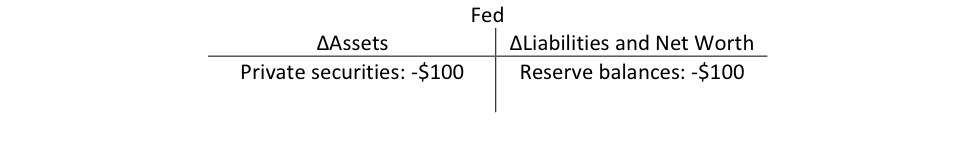

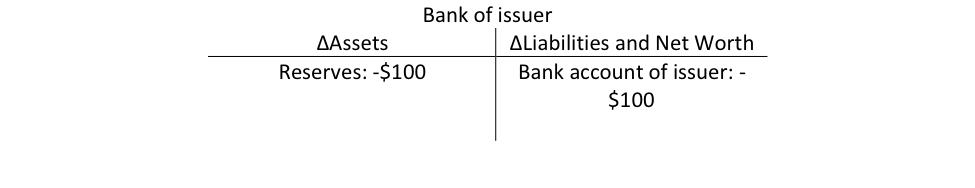

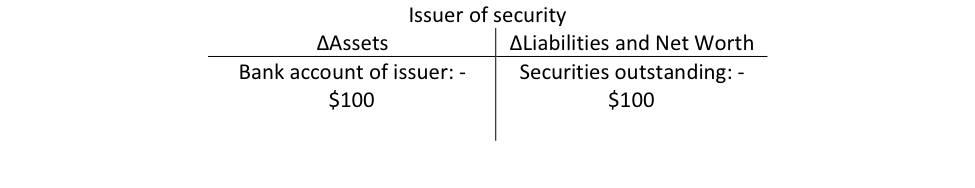

When private securities held by the Fed, currently agency-guaranteed MBS, mature the following occurs:

If all MBS held by the Fed matured at once, that would reduce reserve balances by almost $2 trillion (the Fed does not plan to sell most of the MBS it holds).

Given assets, reserve balances will go down if banks need to make payments to other Fed account holders or if banks convert reserve balances into cash. For example, if the Treasury ran fiscal surpluses, reserve balances would fall as funds would move from L2 to L3. While the Fed may ask, and has asked, for the Treasury’s help in managing monetary policy (see Post 6), the Fed has mostly no control over what happens to liabilities that impact reserve balances.

One may note to conclude that, besides changes in assets and liabilities, another way to reduce excess reserves without reducing the amount of reserves is to raise reserve requirement ratios. As to when the reserves will be back to their usual level, nobody knows. The pace of decline will change as the economic environment change, which brings us to a final point. There is no need for the Fed to be proactive about normalizing its balance sheet because, with the change in monetary policy procedures that occurred in 2008, the Fed can still target the overnight interbank rate.

Q7: Is there a zero-lower bound?

This question is so 2013! There is no lower bound and I have an old post that explains all this in more details. Remember that the Fed sets the price of reserves. It can set it wherever it wants: “It is the Fed’s way or the highway.”

Which interest rate can be below zero? Any of them as long as the Fed is committed to do so.

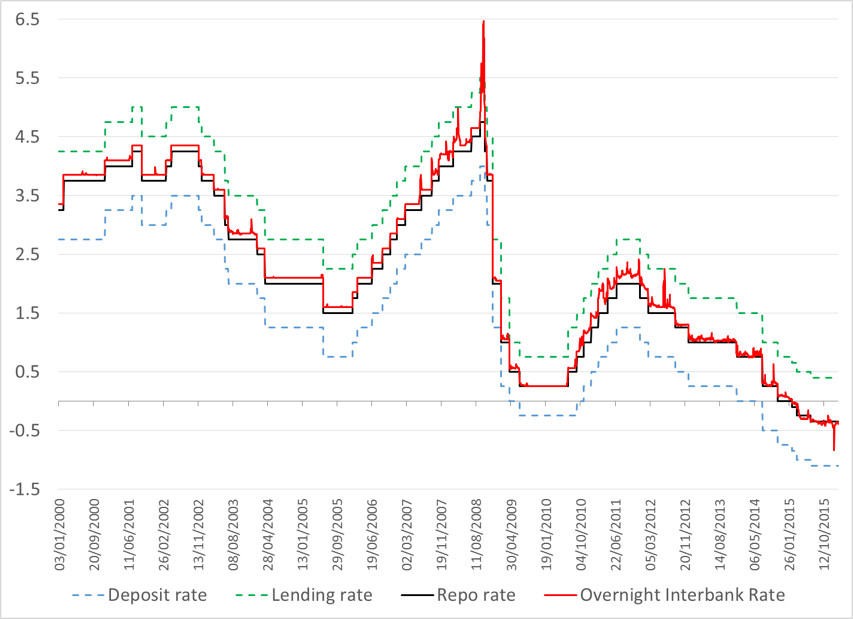

The interest rates used in the corridor framework are under total control of the Fed so they are easy to make negative. The Swedish central bank shows us how this is done under a corridor framework (Figure 4). The Swiss central bank shows us how it is done with a negative overnight interbank rate range (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Target Overnight Rate Range and Daily Overnight Rate, Swiss National Bank, Percent

Figure 4. Corridor of the Sveriges Riksbank, Percent

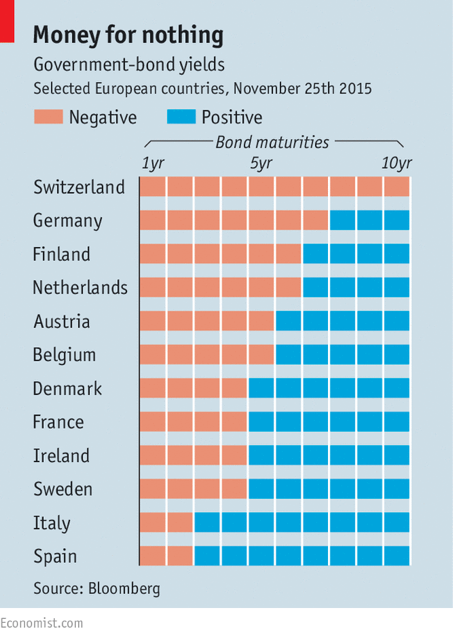

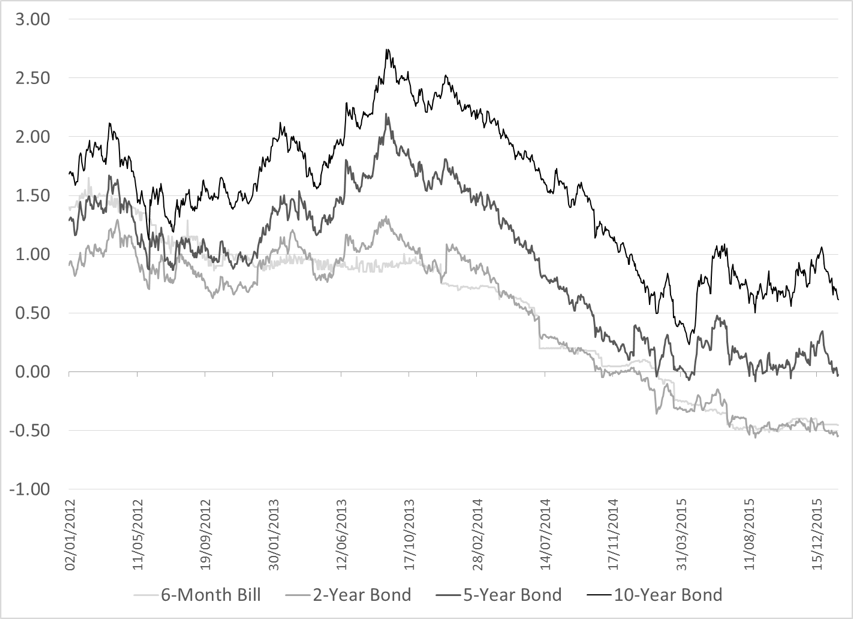

Of course, if a central bank has negative policy rates and is expected to continue to have negative rates for a while, this enters into portfolio strategies and pushes longer-term rates into/toward negative territories (Figures 5 and 6). But, the European Central Bank is going further and is buying large amounts of long-term government bonds. And financial-market participants took notice and bought government bonds in anticipation of the intervention of the ECB. Financial-market participants are so sure the ECB will buy a lot of securities that they are willing to buy at a premium (so yields to maturity are negative) (Figure 4). They will sell to the ECB who will be the one taking the loss by holding to maturity.

For example, take a 1-year zero-coupon government security with a face value of $1000. Normally, this security will trade at a discount, i.e. economic units will only buy it for less than $1000 because it does not pay any coupon. They will earn an income by keeping the security until the Treasury repays the $1000 at maturity. If the security is bought at $800 then the rate of return is $200/$800 = 25% (rate of return is what you get for what you paid for). Rates of return on Eurozone government 1-year securities are now negative because securities sell at a premium. For example, if one has to pay $1200 on a 1-year zero-coupon security and gets $1000 at maturity, the rate of return is -$200/$1200 = -17%. Nobody will want to buy that unless one expects someone else to buy at, say, $1300 in upcoming days or months. The ECB is willing to do so and will take a loss of $300 (-23% rate of return) when the securities mature, while financial market participants make a return of $100/$1200 = 8%.

Figure 5. Yields on Government Bonds

Source: The Economist

Figure 6. Yields on Swedish Government Securities, Percent

Source: Swedish Central Bank

Q8: What are the effects of a negative interest-rate policy?

It depends on which rate is concerned. Let us talk first about banks. A simplified bank profit is this:

Profit of banks = (ROA*other assets + IOR*R) – FFR*fed funds Debt

ROA is the return on assets held by banks (say you have a $1000 mortgage with an interest rate of 5%, this 5% is an income for the bank equal to ROA*mortgage = 5%*$1000 = $50). IOR is interest on reserve balances and R is reserve balances. There are no other debt than those incurred from getting reserves in the fed funds market either from Fed or from other market participants than banks. Interest payments on interbank loans cancel out in the aggregate profit of banks, it is an income for one bank and an expense for another).

- Given everything else, negative FFR raises the profitability of banks because banks are paid to get an advance of reserves.

- Given everything else, negative IOR lowers the profitability of banks. This is especially significant today given how large reserve balances are.

Banks will react to these effects in several ways in order to preserve their profitability. To counter a negative IOR, banks may do three things:

- Ask their customers to pay a fee on their checking accounts (either a larger one or raise the minimum amount of funds in an account below which a fee is paid)

- Raise the bank prime rate (i.e. interest rate paid by the most creditworthy economic units) or acquire for risker assets so as to raise ROA.

- Raise leverage.

If the fee on bank accounts is too large, customers may ask for cash and close their accounts, but that is not really a problem for banks given that:

- If the FFR is negative, banks can borrow all the reserves they need and be rewarded for it. Today they have plenty of reserves so this effect is limited, but it also mean that meeting cash withdrawals is easy.

- Banks work by granting advances and making electronic payments so some individuals must have deposits. In addition, nobody can access cash (Federal Reserve notes) if one does not have an account in the first place, and banks create these accounts by providing advances. Advances pay interest.

The real problem is a negative IOR in the context of a large amount of excess reserves. It acts like a tax and may incentivize banks to take more risks. This effect is all the more strong that banks do not need to borrow in the fed funds market so a negative FFR has a limited ability to offset the negative impact of a negative IOR.

In terms of negative bond rates, the impact is that bondholders make capital gains by selling to the central bank (see Q7). The central bank hopes that bondholders will use some of their capital gains to consume and so stimulate the economy. Given how unequal wealth distribution is, the ability of this channel to work seems doubtful. It is a form of trickle-down economics

Q9: How did central bankers justify using negative interest rates and QE?

Here is the logic followed:

- A negative policy rate in a time of deflation (or low/zero inflation) allows to keep the real interest rate low (allows to lower the real rate). Economic units pay attention to the real rate (interest rate less inflation) when they decide to go into debt. If policy rate goes negative that should incentivize economic units to go into debt.

- By buying a lot of securities from banks, banks will have a lot of excess reserves and will be encouraged to provide credit. And there will be a demand for credit given step 1.

- Now that QE provided banks with a bunch of excess reserves, banks are supposed “to lend” (see money multiplier theory in Post 10). By setting IOR negative, banks will have less incentive to cling on their reserves and instead will provide credit. Indeed if they keep reserves a negative IOR would lead to losses (see Q8).

- Beyond the positive impact of bank credit, negative policy rates and quantitative easing also help push down other rates, which promotes capital gains by securities holders and so consumption.

There are several issues but the three main ones are:

- The ability to banks to grant credit is unrelated to the amount of excess reserves they have. We already saw that banks cannot do much with reserve balances (Post 10 studies private-bank monetary creation). Central banks can feed them tons of reserves and may even threaten banks profitability with negative IOR, but it is just like beating a dead horse; banks are stuck with reserves.

- In a depressed and over-indebted economy, incentivizing economic units to go into debt is the wrong way to proceed.

- The form of trickle-down economics that quantitative easing and negative yield rates represent has never worked.

We need a bottom-up approach that focuses on providing jobs, fighting poverty, and meeting the needs of the nation. Fiscal policy is the means to do so.

Q10: Should the Fed fine tune the economy?

While the Fed is heavily involved in “fine tuning” the economy—i.e. making sure the economy is not too hot (inflation) nor too cold (unemployment) by moving the FFR target up and down—one may note that the Fed (and other central banks) was not created for that purpose. Central banks were created either to finance the crown/state, or to promote financial stability (both goals are actually intertwined as shown in Post 6).

Some economists, like Hyman Minsky, think that fine tuning and promoting financial stability are incompatible goals. A central bank should focus on promoting financial stability through low stable nominal interest rates and proper regulation, supervision and enforcement. The Fed could also influence financial innovations by refusing to accept as collateral any financial instrument that promotes “Ponzi finance” (see Post 14). Fine tuning the economy with interest rates implies raising interest rate during an expansion, which ultimately contributes to problems to service debts. Given that decisions to go into debt are not interest-rate sensitive, raising rates just pushes economic units to go more into debt to pay existing debts. The hope is that income and capital gains will ultimately enable the full repayment of debts.

More broadly, the link between FFR and the end goals of employment and inflation is tenuous and subject to perverse linkages. For example:

- The link between interest rates and business investment is very weak, with investment by companies overwhelmingly dependent on expected cash flows

- Higher interest rate raises the cost of doing business and firms may pass that cost to their client, resulting in inflation

- Higher interest rate also raises the income of rentiers and so their consumption. If the economy has a large proportion of rentiers (pensioners, wealthy individuals, etc.) then this may be inflationary.

- Higher interest rate raises the debt burden and promotes financial instability

- Interest-rate volatility promotes financial innovations to remove the sensitivity of profit to interest-rate swings.

- Increments in FFR are small and announced well in advance, giving plenty of time to economic units to adapt in order not to let their decisions be influenced by the cost of credit.

Instead of nudging incentives so that, maybe, the private sector will spend, some economists promote a more direct approach. In times of crisis, implement large scale fiscal spending to meet the needs of the nations (in the US, one of these needs would be infrastructure that is in really bad shape). At any time, involve the government in direct job creation by employing people in similar way it was done in the New Deal (WPA, CCC, etc); a Job Guarantee program. In times of expansion, constantly check financial innovations and forbid financial practices related to Ponzi finance or at least remove any safety net for them.

Finally, there has been some debates also about how to set the FFR target. In the more mainstream literature, this issue boils down to what to include in the Taylor rule (a rule that determines what the optimal FFR target should be given a state of the economy) and how much weight to put on each element that influences the rule. In the non-maintream approach, the discussion is broader and includes discussions about the distributive and destabilizing impacts of monetary policy. Some authors want the central bank to target a specific interest rate to make rentiers’ income stable and related to the productivity gains of the economy. Others want to “park” monetary policy by leaving the FFR permanently low and by letting other rates do the job of sorting credit risk, inflation risk, etc. A positive FFR just adds extra income to rentiers and does not reward any risk.

For your reading pleasure below are three extracts from some Federal Open Market Committee meetings that illustrate some of the previous points. First on the lack of interest-rate sensitivity:

In addition to the input that we bring to these meetings and the usual sources of our own research staff and directors, last Friday when Vice Chairman Schultz visited us in San Francisco we called in a special small group of bankers, businessmen, and academicians for a very frank exchange of views. We sounded them out about their feelings on the economy and on Fed policy, and I must say, Fred, that I thought the reactions were quite candid and somewhat humiliating in a way. The bankers generally expressed the view that as yet there’s very little evidence that the high level of interest rates is having any significant total effect on cutting off credit demand. Now, one has to add to that the expressions we got from them in our usual go-around with bankers and bank directors that these high rates are having a cutting effect on the so-called middle market for business borrowers – the smaller firms – and for mortgage loans and some small farmers. That’s where the incidence of the high interest rate effect has been felt thus far in our part of the country. But as a general matter, even if the businessmen present were mostly from big concerns, they simply indicated that the higher rates per se are not having any effect at all on their capital projects. If a project is worthwhile, it‘s not going to get cut off by a one or two percentage point increase in the cost of funds. A minority expressed the view that this is leading to some greater caution on inventory policy, which is already being viewed as quite cautious. One major real estate developer present indicated that the higher rates are just built into their projects and aren’t having any dampening effect at all. (Balles, FOMC meeting, September 1979, page 27)

Second on the cost impact of raising interest rates:

Interest rates may be [low] after tax, or in real terms, but they are still contributing to cost and are creating, I think, some of the upward pressure on prices. (Teeters, FOMC meeting, May 1981, page 10)

There is deterioration in the inflation rate stemming from interest costs and energy costs, and those are not trivial sources of deterioration. At the end of the day it doesn’t have to be labor costs that are causing the overall inflation deterioration. (Greenspan, FOMC meeting, November 2000, page 85)

Q11: Is the Fed a private or a public institution?

Partly due to the culture of the United States, and partly due to strong economic interests against centralized institutions, the Federal Reserve System is oddly organized public-private partnership. Member banks do hold stocks issued by the System that provide a dividend payment but this dividend payment is not guaranteed, the stocks do not provide any voting rights, and they cannot be traded. For example, recently Congress decided to divert some of the dividend payments to fund highway expenses.

In addition, all leftover income of the System must be transferred to the Treasury. Note that this makes for an odd situation. The Fed holds treasuries that pay interest, part of this interest income ends up going back to the Treasury: the Treasury pays itself interest! In addition, the Treasury tries to maximize its earnings from the Fed through cash management (see Santoro page 7ff.)

Instead of looking at stock holdings and income payment, a more relevant analysis of the political economy of the Fed looks at its structure and who can make decisions regarding monetary policy and emergency operations. In terms of monetary policy, the influence of the Wall Street is large with strong representation on the Federal Open Market Committee via members with former ties to major banks (half the Fed presidents have former ties to two major banks: Goldman and Citibank). Financial sector members tend to be more hawkish and more concerned by, if not obsessed with, price stability. This leads them to want to raise the FFR target early, leading to a level of employment lower than it would otherwise have been. They are also friendlier to the financial industry and more lenient in terms of regulations and in terms of response to a financial crisis. Finally, there is a risk of regulatory capture.

If one combines this with the fact that economists at the Board are mostly pro-market supply-sided economists (economic growth is ultimately a supply-side thing), financial regulation and enforcement do not make much sense and raising rate very early in anticipation of inflation makes sense. Many economists, however, doubt that markets are efficient and that demand has no role to play in the long run.

Q12: What are no-no sentences for what the Fed does? (Will give you a zero on my assignments)

- “The Fed controls the money supply”: No, it does not, it sets an interest rate (what happens after that is up to firms and households and their desire for external funds)

- “The Fed injects reserves which lowers the interest rate” or, worse offender, “The Fed injects money which lowers interest rate”. Under normal circumstances (i.e. pre-Great Recession, which is what most people have in mind when saying this), the Fed does not proactively inject reserves, it waits for banks to ask. And, the Fed’s monetary policy never injects money, i.e. never deals directly with the public (M1).

- “The Fed printed money during the financial crisis”: No it just credited account by keystroking amounts, no Federal Reserve notes were printed. More to the point, none of these funds entered the money supply, i.e. funds held by the public.

- “The Fed used taxpayers’s money during the financial crisis”: No, it just credited accounts of banks by keystroking dollar amounts.

- “Banks use reserves to buy stocks and corporate bonds”: No banks can’t do that with reserves

- “The large inflow of reserves in banks did not lead to inflation because banks did not lend the reserves or based on reserves”: No, banks do not operate that way, bank credit and amount of reserves are unrelated (see Post 10)

- “Central banks lend reserves”: No, the Fed does not lend reserves because reserves are its liability.

- “Fiscal deficits raise interest rates”: No, there was a hint about this in Post 3. More is coming in Post 6.

[Revised 7/21/2016]

9 responses to “Money and Banking – Part 5: FAQs about central banking”