By Rob Parenteau

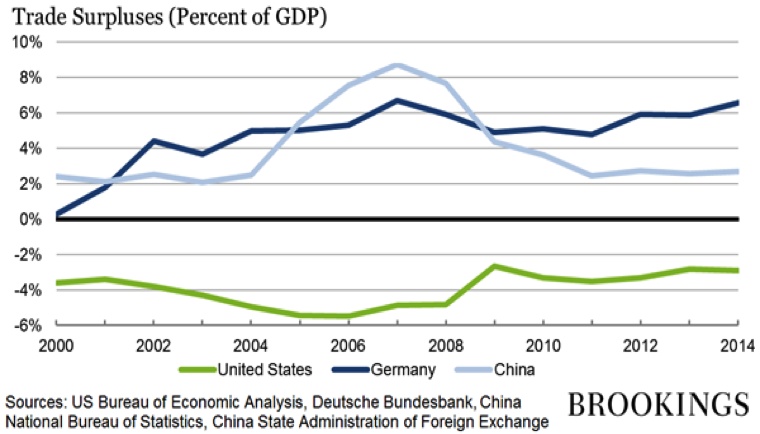

That Germany has pursued something of a neo-mercantilist growth strategy is no great secret. Even newly minted econoblogger Ben Bernanke (apparently, Fed Chair pensions are not what they used to be) has duly noted Germany’s ascension to the throne of the Chief Instigator of Global Imbalances (CIGI) in his post dated April 3, 2015 (see here). At 7% of GDP, Germany’s trade surplus has clearly unseated China’s prior well-vaunted position as CIGI. Clearly, Frankfurt, not Shanghai, has become the new capital city of Global Saving Glutistan, in the nation of West Secular Stagnationa.

To his credit, and also as a shining example to his fellow New Keynesians (who, as we detailed in our previous piece on Paul Krugman – see here – are not really Keynesians at all, but rather Old Pre-Great Depression Fisherians, or possibly New Friedmaniacs and Wacky Wicksellians), Gentle Ben revives the simple yet powerful point that Lord Keynes attempted to make a lifetime ago, and was enshrined in a somewhat diluted fashion in the enabling legislation of the IMF (see, especially, the notorious scarce currency clause), but was largely ignored or betrayed by the American negotiating team as they were determined to cement into place America’s prospective post WWII status as the Imperial Creditor du jour. Keynes was too hopped up on truth serum (an unintended side effect of his heart medicine, according to one recent account) to completely outfox his opponent, the communist spy William Dexter White, who was leading the American delegation at Bretton Woods, but Keynes’ line of march was clear. In the case of chronic current account imbalances, the burden of adjustment must necessarily be placed on the current account surplus nation, if a pro-growth solution, rather than a deflationary “solution”, was the preferred outcome.

Germany’s status as the penultimate chronic current account surplus nation within the eurozone has also been duly noted as an indication of one of the central design flaws in the EMU. There is no explicit policy mechanism, nor does there appear to be any spontaneous market driven Invisible Hand, that channels the money earned from a chronic current account surplus back into productive and profitable investments that can enhance the capital stock and the competitiveness of tradable goods industries in the chronic current account deficit nations. None.

Instead, in the case of the eurozone, current account surpluses got recycled in the financing of housing bubbles and household deficit spending in many peripheral nations, with the predictable sudden stop issue rearing its horrifying head once the Global Financial Crisis went full tilt in 2007/8. And so it is nearly inevitable that the chronic current account deficit nations will eventually default on their external liabilities that build up over time with these persistent trade imbalances, often taking the core financial institutions in the eurozone down with them – unless of course these costs can be externalized and socialized, by sending the bill to taxpayers, as we witnessed circa 2010 in the eurozone. The lenders, in other words, are equally culpable, in playing a financing game that they must know, on the basic math of it, could only end very badly, as the loans they were making were not, generally speaking, improving the capacity of trade deficit nations to earn the income required to service this external private debt.

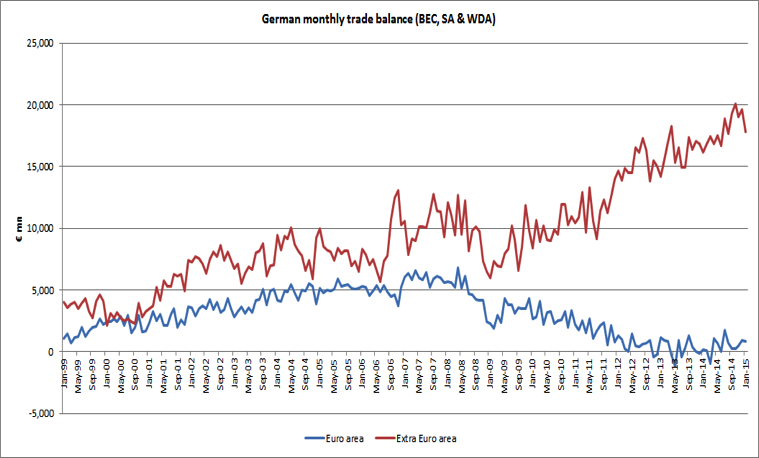

Now as compelling as the logic of this criticism of the EMU may be, and as welcome as it is to hear a New Keynesian like Ben Bernanke actually echoing an idea that Keynes actually professed and pursued in real world policy proposals, there is a little problem with this story. As Raoul Ruparel pointed out in a subsequent blog (see here), Germany’s magnificent and oh so virtuous trade surplus has gone to hell with the eurozone as Austerian policies have cratered final demand in the periphery, while Germany’s trade surplus with countries outside the eurozone has surged since the GFC.

While the first result was anticipated by those of us who were warning in 2010 about the self-inflicted wounds the core would end up imposing on their own tradable goods sectors, as well as on their own financial institutions (see in particular points 9 & 10 sketched out in somewhat prophetic fashion herein), the second accomplishment clearly was not widely anticipated. In addition, recognition of the shifting composition of Germany’s trade surplus may also hint at some of the reasons why German policy makers may not be terribly interested in Ponzi financing the external liabilities of peripheral eurozone governments much longer. After all, the periphery no longer appears to be where the main customers of their tradable goods companies dwell any longer. It is, in other words, not inconceivable there may be a Germexident before there is a Grexident, as Germany has less to lose with respect to its neo-mercantilist growth strategy now if the peripheral economies are left to fend for themselves in servicing their existing external debt loads. Recall also, as depicted in a recent piece called Draghi’s Doom Loops (see here), that the profitability of Germany’s banks and insurance company is also being undermined by the ECB’s PSPP initiative.

For the time being, however, the result of the rabid pursuit Austerian policies has essentially made somewhat obsolete the hand wringing over the eurozone current account recycling mechanism design flaw that can be found in places like Yanis Varoufakis’ masterful treatise, The Global Minotaur. We will simply have to wait with baited breath for the second edition to be scribbled and released once the Troika has insured the current Greek Finance Minister will have much more free time on his hands.

This brings us to what we can and should recognize as Herr Schauble’s Foibles. For you cannot possibly ask a country that has pursued a neo-mercantilist growth strategy to just drop it. You especially cannot expect a warm, favorable response from said country when key policy authorities and their key economic advisors, believe the whole world can (and should) follow in its virtuous footsteps by also running trade surpluses – a bold challenge to the rest of the world which unfortunately ignores the small algebraic fact that global trade balances have to net to zero. At least, that is, until we open up trade with Martians and Venusians.

You especially cannot expect to get anywhere by asking a neo-mercantilist nation to just drop it and take steps to deliver a trade deficit, if the policy makers of that nation also believe it is equally virtuous to maintain a fiscal balance near zero. Simply put, if you take away their trade surplus as a driver of growth, that means they can only get growth if their domestic household or business sectors are willing and able to deficit spend in perpetuity.

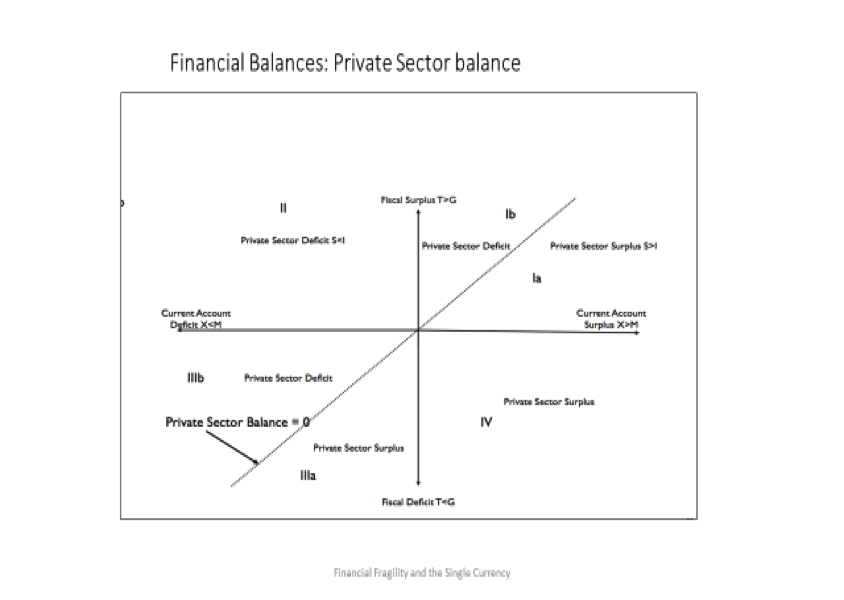

This surprising conclusion follows from the macrofinancial balance (MFB) equation, which simply says the income and expenditures of the Government, Foreign, and Domestic Private Sectors must net to zero in any accounting period – a result of double entry book keeping, not of high Keynesian theory.

Domestic Private Financial Balance + Government Financial Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

or

DPSFB + GFB – CUB = 0

An elementary derivation and application of the MFB equation can be found in Jan Kregel’s recent piece at the Levy Economic Institute entitled Europe at the Crossroads (see here). In particular, this point is made very clear on p. 7, chart 5, reproduced below. In the MFB map, fiscal balances appear on the vertical axis, while current account (largely trade) balances appear on the horizontal axis. The 45-degree line running from the southwest to the northeast depicts all those points on the MFB map where the DPSFB is zero (meaning households and nonfinancial businesses are spending exactly the amount they are earning), and CUB is equal to the GFB. The region to the right of this 45-degree line depicts zones where the domestic private sector is running a surplus or net saving position on its financial balances, while the zone to the left depicts zones where households and firms are deficit spending.

Jan has further classified the zones of the MFB map to clarify the state of the DPSFB under various possible combinations of the GFB and the CUB.

Assuming the diktat of fiscal responsibility means that no persistent deviation from a GFB = 0 is allowed, and assuming a chronic current account surplus nation is required, under some plausible global rebalancing criteria, to run a deficit, the DPSFB can only inhabit points along the horizontal axis that are to the left of the origin or intersection of the GFB and CUB axes. Note that all points on this section of the CUB axis, as well as all points close to it in sectors II and IIIb, are areas where households and firms are chronically deficit spending.

Or to put it another way, because the CUB is less than the GFB, more net income is flowing out of the DPS. And of course, the larger the current account deficit that is targeted for a former CIGI, the deeper the resulting deficit spending by domestic firms and households, and the larger the build up, over time, of debt to income ratios (specifically, in this case, external liabilities) in the DPS. A demand for trade deficits placed on a CIGI nation like Germany that also wishes to pursue the virtues of fiscal responsibility, is implicitly a demand that, for example, Herr Schäuble be prepared to guide German households and firms onto a trajectory of increasing financial fragility, and inevitably, a severe and possibly debilitating financial crisis. This is not really a very reasonable demand at all.

Ignoring, for the moment, that slight stumbling block, there are other practical difficulties with the proposal that Germany rebalance its trade/current account. German companies, like most of the rest of the Western world, are not so interested in reinvesting profits in capital spending, at least not in Germany itself. The incentives to extract profits by driving productivity gains well in excess of real wage gains (a blatant violation of the marginalist law of distribution that sits at the heart of neoclassical economics, and is also trumpeted as another justification for the virtues of free exchange in capitalist economies), and to then redistribute those profits to shareholders and managers who own stock and stock options, all ostensibly in the service of maximizing shareholder value, are just too strong. Maximizing free cash flow is the corollary to maximizing shareholder value, and this the same thing as minimizing the reinvestment of profits in productive capital equipment and structures, hence minimizing long term economic growth prospects. So unless incentive structures associated with corporate governance and institutional investor behavior change, Germany’s GDP growth is unlikely to be fueled by corporate investment in excess of profit incomes.

Germany’s households are notoriously conservative and prudent, so they tend to maintain a high and steady gross saving rate of between 10% and 12% of income. In addition, they tend to rent rather than own their homes, so they usually do not get caught up in real estate bubbles (though a housing bubble appears to be starting to brew in Germany of late, and this has been a repeated fear of the Bundesbank) and the household deficit spending associated with those bubbles. In addition, as mentioned above, Germany’s neo-mercantilist growth strategy has required real wage suppression, which tends to hold back the growth of household purchasing power. With real wages growing more slowly than productivity (which is also growing more slowly, closer to 1% vs. the 2.5-3.8% achieved over the half-decades from 1970-1995, because of low corporate reinvestment rates – so perhaps you can now see how this all is nested and cumulates in an increasingly disequilibrium fashion over time), households cannot possibly buy all that they produce without net selling assets to another sector, or increasing their debt loads.

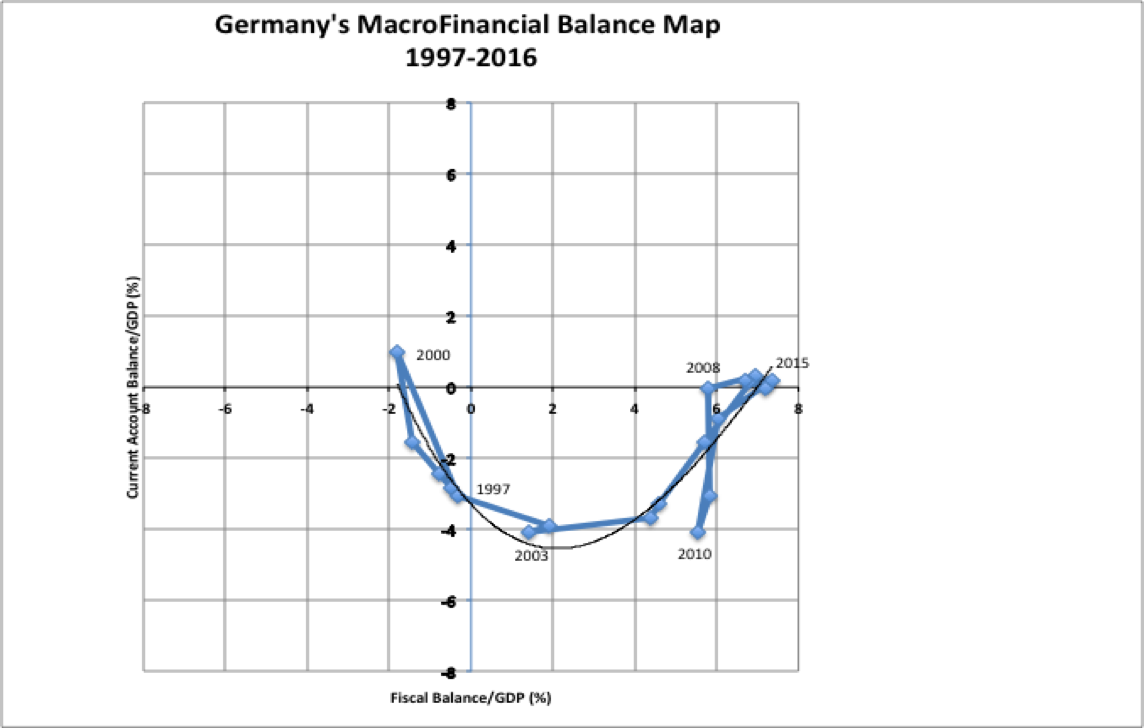

In other words, Germany’s households and firms are unlikely to be terribly interested in chronic deficit spending – a deficit spending that must be sustained if the GFB is to be kept close to zero, and the CUB is to be kept in deficit. A quick glance at the actual migration of the DPSFB over the past nearly two decades reveals that in fact, the German private sector has sought and achieved increases in its net saving position, from a low in 2000 with a DPSFB/GDP of -2.8%, to a peak of 9.6% in 2010. Germany’s private sector net saving position is closer 7% of GDP in the last few years, which must mark one of the highest, if not the highest DPS surplus amongst the mature economies.

Even if you were able to convince some German companies to reinvest their export earnings in productive capital equipment in their trading partners in the eurozone periphery, as Keynes would have recommended for any sustainable current account rebalancing mechanism, these companies would likely be accused of undermining Germany’s trade driven growth strategy, as German imports would increase, or companies based in Germany competing in those tradable goods sectors would face margin squeezes as the tried to maintain market share in the face of more competitive foreign producers.

So as beautiful as Keynes’ ideas about rebalancing trade may be, with the onus being placed on the chronic current account surplus nations, it is hard to see how you could convince Germany to take the bait. At a minimum, they would have to implement policy measures that encouraged or forced domestic non financial firms to reinvest their profits in their home country, so these companies would actually be serving the accumulation function that capitalist firms are supposed to perform to generate the benefits of rapid growth and development. The promise of rapid growth through profit seeking and profitable reinvestment activity was, after all, supposed to be the reward for putting up with capitalism’s various shortcomings, including routinization and speedup of work, frequently externalized costs, widespread corrosion of social organizations and “social capital” outside the capitalist firm, as well as the destruction of the biosphere – a consumption or degradation of “natural capital” which has become all too obvious in recent years with climate disruption and the acidification of the oceans.

To conclude, if Herr Schäuble believes the whole world should follow the virtuous neo-mercantilist growth strategy that has served his homeland so well, he may want to consider the fact that he is facing a small adding up problem with that ambitious policy prescription, barring the discovery of life elsewhere in the solar system. While Germany’s massive trade surplus has become less of an issue since 2008 for the eurozone – as a predictable but perhaps unintended consequence of the Austerian demands placed on the periphery – it has not become less of an issue for the world. Herr Schäuble still appears to be the Finance Minister of a nation that qualifies as a CIGI.

Well intentioned calls for Herr Schäuble to rethink and reverse his neo-mercantilist tendencies run into another unrecognized and unintended consequence, but one which can be made perfectly coherent by recognizing the constraints imposed by the simple algebra of the macrofinancial balance equation. If Herr Schäuble could somehow be persuaded to take on the vice of trade deficits while at the same time he insisted on maintaining the virtue of a balanced fiscal budget, he would unwittingly fall into the trap of consigning his nation’s firms and businesses to a path that ultimately must lead to financial instability, and possibly even a financial crisis, along the lines that Hy Minksy depicted decades ago. Alternatively, if he instead agreed to a current account surplus recycling mechanism of some sort, he would be inviting the eventual undermining of the competitiveness of his own tradable goods companies, as well as the eventual erosion of his highly valued and virtuous trade surplus – not a high odds bet, at all.

Herr Schauble’s Foibles are many. But of course, these foibles are not merely his, as they belong to a deeply entrenched neoliberal consensus in the economic profession (if we dare call such a frightful circus by that name) which has, as more an more people appear to be recognizing, judging by the 700 or more people attending the Institute for New Economic Thinking’s confab in Paris this week, outlived its usefulness on this planet. Herr Schäuble cannot be expected to pursue the vice of a trade deficit if he is going to hold fast to the virtue of balanced fiscal budgets. Nor is he, or any other finance minister of a nation pursuing a neo-mercantilist growth strategy, like to be terribly interested in recycling trade surpluses into tradable goods industries in chronic trade deficit nations, thereby financing his own competitors. Nein, nein, nein.

Crafting new solutions, like the Greek Finance Minister’s proposal that he reiterated during Thursday’s afternoon session at the INET conference (see here), to have the European Investment Bank play a much larger role in recycling these surpluses into infrastructure investing in the periphery, may indeed point in the direction of promising new design solutions for the eurozone and beyond. But until we recognize the binds that neoliberal faith based economics have tied our policy makers with, and until we jettison the neoliberal liturgy that is spewed daily in the mainstream media, in universities, in central banks, and in Treasury departments around the world, Schauble’s Foibles will continue to rule the roost, and more unnecessary suffering will have to be endured by more nations. Perhaps it is time to admit we can do better than that – a lot better, in fact.

3 responses to “Herr Schauble’s Foibles: The eurozone Rebalancing Conundrum”