By Stephanie Kelton

I’ve grown increasingly frustrated by the near universal cry for more action from the Fed. My friend and fellow blogger Marshall Auerback has quipped that it’s as if every mainstream progressive received the same White House memo. I imagine it looked something like this:

MEMO

To: Mainstream Media (TV, Radio, Print Media)

From: Office of the White House

Date: June 10, 2012

Re: Messaging on the RecoveryThe economic recovery is faltering. The fiscal cliff is nearing. Many nations have already fallen back into recession. The net worth of a typical American family is down almost 40 percent since the start of the crisis. Unemployment is rising. People are worried about keeping their jobs, holding onto their homes and paying down the enormous debts they accumulated over the last decade or more. The bloodletting at the state and local government level continues unabated, and this is compounding our economic problems. Consumer confidence is down, and small businesses are struggling to remain profitable.

Some of you have written about the mistakes of our past, pointing out the trauma that was inflicted in 1937, when FDR decided it was time to move toward a balanced budget. Please stop that. This is an election year, and I cannot afford to be viewed as soft on the deficit. Besides, Congress will not support anything I put forward, so we’ve got to enlist the help of an independent body like the Federal Reserve if we’re going to improve things before November. So here’s what I need you to do — scapegoat the Fed. Call them out, repeatedly, for “sitting on their hands.” Demand that they do more. Tell them that “country trumps credibility.”

Message received! Krugman, Baker, Yglesias, Hayes — everyone seems to have gotten the memo. Ordinarily, they insist, the Fed could reach into its tool kit and deliver a powerful shot of economic adrenaline that would set off a frenzy of borrowing and spending. But that typically potent transmission mechanism is said to be broken because borrowing costs are already essentially zero. The curse of the so-called Zero Bound! What to do? The Fed must move into uncharted territory. It must “do more.”

And so instead of building a powerful, unrelenting case for further fiscal easing, mainstream progressives are focused on the Fed, demanding that it do just as much to promote growth and employment as it does to promote price stability. How? By following Krugman’s advice and “credibly committing to a higher inflation target,” which, it is argued, will stimulate spending by lowering the real rate of interest. It’s a policy recommendation that only an economist (or someone with enough credit hours to be dangerous) could conjure up. I almost hope the Fed tries it so that we can banish this proposal to the wasteland of failed policy recommendations (along with QE1, QE2 and Operation Twist). But millions of Americans are suffering and so I really do not want to see us pursue a losing policy just because the alternative looks like a political nonstarter.

The zero bound isn’t the problem. Brazil’s central bank has cut its policy rate by 400 basis points since August 2011. That’s 4 percentage points in under a year! Meanwhile, growth continues to slow and inflation is falling. Why? Brazil isn’t up against the zero bound (far from it, rates are at 8.5 percent). The problem is that monetary policy is a blunt instrument (at best). Committing to a higher inflation target isn’t going to pull us out of the economic doldrums.

Dean Baker has argued that the Fed could push long-term rates down another 20-30 basis points, which could allow some Americans to refinance their homes, freeing up a bit of their take-home pay for other uses. But I wonder how many people would do what I did when long-term rates fell to historic lows. I refinanced from a 30-yr fixed to a 15-year fixed mortgage and consequently spend less on everything else!

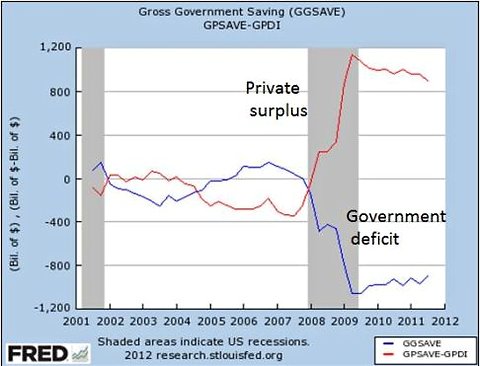

In any event, we’re in a balance sheet recession. We should be encouraging the private sector to borrow less, not taunting people with negative interest rates and encouraging them to leverage up. And we should recognize that the government’s deficit is the key to helping the private sector de-leverage.

Reducing the government’s deficit means cutting the non-government’s surplus, which frustrates their efforts to pay down debt.

We need rising incomes to support a recovery that can be sustained by private sector spending, and the Fed isn’t the agency we should be looking to for help on this front.

Pingback: Can the Fed Really Do More? « naked capitalism

Pingback: The Fed cannot save the day | Credit Writedowns

Pingback: Links 6/27/12 | Mike the Mad Biologist

Pingback: Epicene Cyborg

Pingback: Renzi dalla Merkel non mi pare il nuovo che avanza | Carlo Costantini