By J. D. Alt

Why does it seem like there isn’t enough money to pay for the things we really need? The headlines are filled with stories about our nation’s “debt problem” and dire warnings about our impending “bankruptcy.” As an architect who fills his waking hours thinking up all kinds of wonderful things we could be building, I’m alarmed by the idea there isn’t enough money to pay for any of them. Before wasting more time dreaming, I had to find out: Is it really true? Are we really too poor to put America back to work making and building the things we need to maintain a prosperous nation?

Why does it seem like there isn’t enough money to pay for the things we really need? The headlines are filled with stories about our nation’s “debt problem” and dire warnings about our impending “bankruptcy.” As an architect who fills his waking hours thinking up all kinds of wonderful things we could be building, I’m alarmed by the idea there isn’t enough money to pay for any of them. Before wasting more time dreaming, I had to find out: Is it really true? Are we really too poor to put America back to work making and building the things we need to maintain a prosperous nation?

Searching for an answer, I discovered a small (but growing) group of economists (see here, here, here, here, here, here) who represent an emerging school of thought known as “modern monetary theory” (MMT). These men and women are valiantly trying to make us all understand a paradigm shift that occurred some forty years ago, when the world abandoned the gold standard. Their key insight shocked me: A sovereign government is never revenue constrained when it is the Monopoly issuer of its own pure fiat currency; it has all the money that’s needed to put its citizens to work building anything—and providing any service—that is desired by the public (provided the real resources are available). Even more remarkable, sovereign “deficits” in the fiat currency are just the accounting record of the surpluses that have been injected into the private economy. Eliminating the sovereign currency deficit by imposing austerity will not make the economy healthier; it will, in effect, bankrupt the citizens!

If this seems to defy logic, stay with me for just a few minutes. I’m going to propose a simple exercise that will help you “see” this reality for yourself. The exercise is simply that everyone join me in a familiar game of Monopoly. By the end of the game, I hope to convince you that MMT is correct and that we could be doing better, much better – for ourselves and future generations—if we just understood and took ad vantage of our modern monetary system.

Let’s begin.

Playing Monopolis Monopoly

We’ll play by the normal rules (I’ll suggest some added features as we go along) except this time we’ll pay special attention to certain things that are happening. For example, you’ll recall that before the game can begin, one player has to agree to be the “banker” (a tedious task, but someonehas to do it.) But now choosing this person has a special importance: it must be done democratically, with the players voting to determine who will manage the game’s money. We’ll do this little exercise because we want to pay special attention to the fact that the Monopoly “bank” is an entity created by the players themselves for their mutual benefit. In fact, we won’t refer to it as the “bank” anymore, but instead will call it our “currency issuing government” (CIG). In a real sense, we all “own” CIG together, and taking a minute to democratically choose who will manage it heightens our awareness of this key fact.

To reinforce this awareness, the next thing we’ll think about, as we set up the Monopoly board, organize the Deed Cards, shuffle the Chance Cards and choose our tokens, is that what we are really doing is setting up, and getting ready to operate, a miniature nation-state. Let’s even give it a name: Monopolis. We, the players, are the new citizens of Monopolis. We have just established, through democratic consensus, our currency issuing government, and we are now getting ready to operate our economy. That’s what the game is about.

Issuing the Currency

As we get ready to play, we immediately discover an odd dilemma: CIG has all the money! We, the players, are ready to go but we can’t start the game until we have some of CIG’s money. This is an awkward moment, which is dispensed with so quickly in regular Monopoly we hardly notice it. (The “banker” is instructed to make initial cash distributions in the amount of $1500 to each player). If we pay attention, we can see that this moment raises some interesting and crucial questions.

The first question is: are we not playing the game backwards? Isn’t it us, after all, who have to give our money to government before it has any money to spend on anything? Politicians are telling us this all the time: “Your tax dollars are going to pay for this or that.” And, as will become clear, at the state and local level, this is certainly true. But at the federal level—at the level of the sovereign state—the game of Monopoly provides us with our first clue that something is fundamentally different now from what we habitually imagine it to be.

The CIG we’ve created for our nation of Monopolis, in fact, has exactly the same purpose, and exactly the same unique and special power as any government that issues its own sovereign currency: Its purpose is to issue and manage the money we are going to play our game with, and the special power we’ve granted it is the ability to create as much money as necessary for our game to go on as long as we want it to.

Indeed, the rules of Monopoly specifically state that while players can run out of money (in which case they are bankrupt and out of the game) the Monopoly “bank” itself can NEVER run out. In the event the game unfolds in such a way that all the pink and green and blue and gold bills that come in the box are absorbed by the players, the Monopoly rule book instructs the banker to get out a pencil, paper and scissors and create new money as needed. (This is the definition of “fiat money”—money that gains its acceptance simply by decree.)

So it appears we aren’t playing the game backwards after all. The currency does flow from CIG to the players, and when we give some of that money back—in the form of taxes, or fees, or fines— by logic it cannot be because CIG needs that money. In fact, the CIG could take all the money it receives (in taxes, fees or fines) and simply shred it and throw it away: it has no need for it, because when it needs money it simply “issues” the currency. The first time I tried to wrap my thinking around this set of ideas my primordial brain-stem resonated with knee-jerk objections. (I’m not alone. See here)

Indignant as I might get, however, Monopoly forces me to realize that if I want to play the game, I have to accept the fact that the CIG gets to create the money, and I have to use the money it creates. I could insist otherwise, demanding that each player bring to the table his own private stash of gold and silver. In fact, it was just forty years ago that the real world played the game in exactly this way, and the long history associated with that experience is what implanted our brain-stems with Neanderthal beliefs about what money is and how it works. But as will become evident (if we can ever get started) the game proceeds with much greater efficiency and potential for economic growth (prosperity for more and more people) if we use our CIG’s fiat currency, which has an unlimited supply, as opposed to the player’s “gold and silver” which has a limited quantity.

Monopolis Players have Jobs

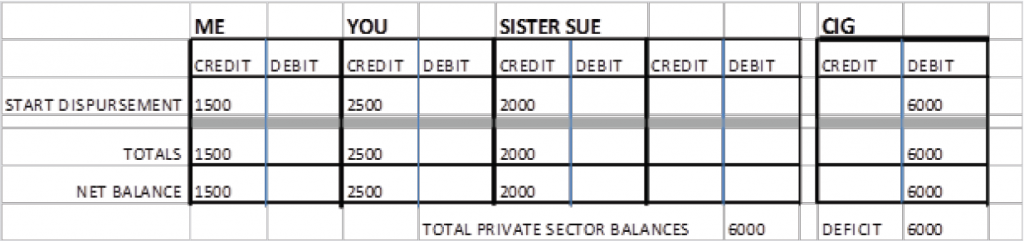

As I mentioned, “plain-game” Monopoly glosses over all these issues by directing the “banker” to simply make initial cash disbursements of $1500 to each player. In our game of Monopolis Monopoly, however, we want to emphasize that people work for a living. So we begin our game by having our government buy something it needs from each of the players.

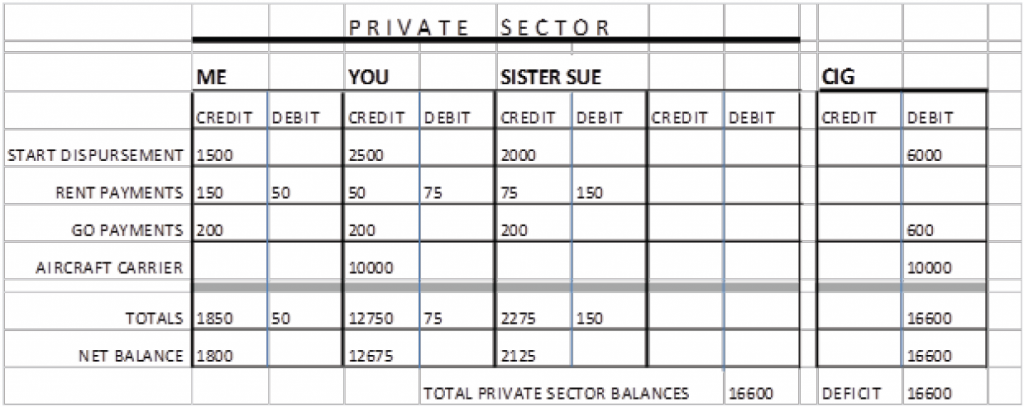

For example, I’m a writer-architect, and the government pays me $1500 to write the Monopolis rules. You are a builder, and the government pays you $2500 to build a network of roads that will allow lumber and materials to be transported to the Monopoly board properties. Sister Sue is an administrator, and the government pays her $2000 to create the Balance Sheet we’ll use to keep track of the game’s transactions. So now we’ve each done a bit of work, have modest cash positions, and we’re ready to begin the game. Before we do, however, let’s look at the Balance Sheet sister Sue has created. Keeping this Balance Sheet up to date, and paying attention to it from time to time, is going to be important.

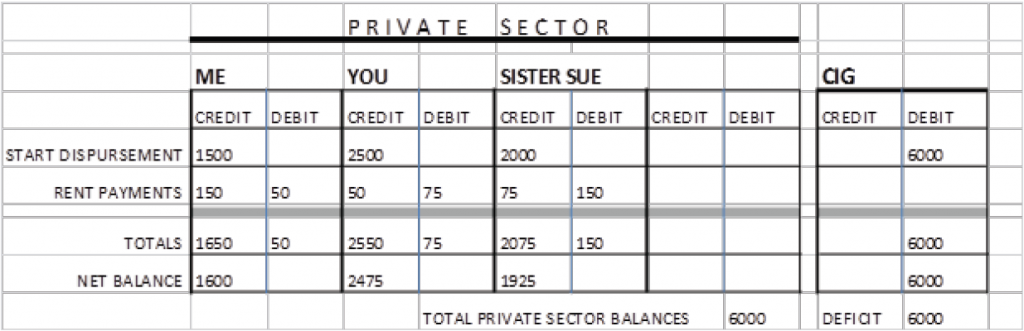

Finally! We’re ready to roll the dice to see who goes first. As we play, we should begin to notice the fact that there are two different kinds of transactions occurring. One set of transactions takes place among the players themselves: I land on your property and have to pay you rent. Let’s say I land on Vermont Avenue and I have to pay you $50; then you land on Baltic Avenue and have to pay Sister Sue $75; then Sister Sue lands on Charles Street and has to pay me $150. Let’s think of these transactions as happening within something we can call the “private sector”, and update our Balance Sheet to look like this:

Horizontal and Vertical Transactions

MMT economists refer to the transactions within the private sector as “horizontal” transactions. These include all transactions between households, businesses, corporations and state and local governments. What they call “vertical” transactions are those between the private sector and CIG.

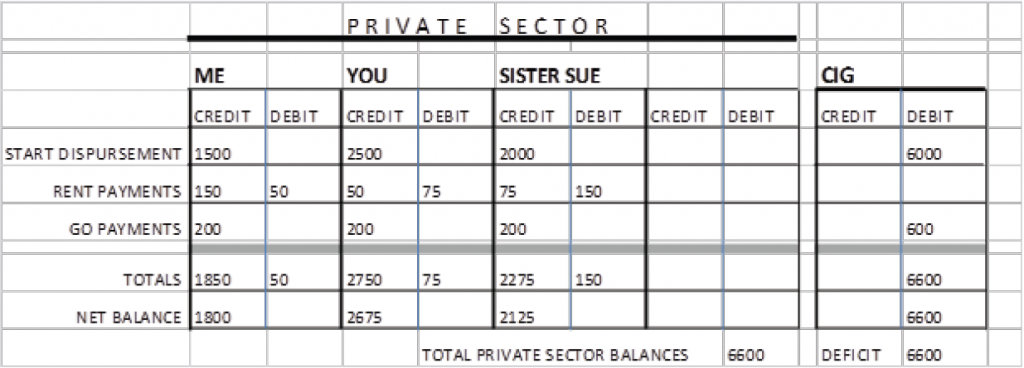

Our government’s initial procurements of services from Me, You and sister Sue were vertical transactions. We can observe another vertical transaction the first time a player passes Go. When this happens, Monopoly stipulates that the “banker” will pay that player $200; it will then continue with the same payment to each player each time they pass Go throughout the game.

We can think of these “Go payments” as being analogous to many different things in the real economy—the federal government paying someone to mow the front lawn of the White House, for example, or sending out a social security check to our grandmother. At this point, it doesn’t really matter. What we do want to notice, however, is what these “vertical” transactions do to the Balance Sheet. Let’s say each player has now passed Go:

What we can clearly observe is that while the Private Sector continues to be a zero-sum game, the “vertical” transactions generated by the “Go payments” have increased the size of that sum. And, once again, the new total of currency assets in the private sector is exactly equal to the “deficit” debit account of our CIG. (Indeed, how could it be any different?)

Expanding the Economy

Now let’s add some “fiscal events” to make our game more interesting. The first “Fiscal Event” I propose is the building of an aircraft carrier. It’s a well-known fact that governments like to purchase aircraft carriers, so it is entirely reasonable to suppose that our little nation-state would like to have one as well.

We can get an aircraft carrier into our game in exactly the same way the U.S. government gets one into its fleet: It goes to the Newport News shipyard and buys one. In Monopolis Monopoly, we’ll simulate this event by pretending that one of the players is the shipyard—You, for example, since you’re the builder amongst us. You give Monopolis its aircraft carrier and CIG pays you for this good by injecting $10,000 into your currency account.

What’s worth noticing here is that this vertical transaction has injected a considerable amount of currency into our game, but that money has been used to build something that does NOT add to the inventory of things that players can buy. Since none of the players in the private sector have any need for an aircraft carrier, our choices of things to spend our money on are still limited to the properties on the Monopoly board and the houses we can build on them—only now we’ve got a lot more money to throw at those things. In one sense, then, the government’s decision to build an aircraft carrier, while it may benefit our common defense, doesn’t really expand the economy of our game. That’s something to think about.

Building Codes and Government Regulation

Politicians argue a lot about whether government regulations are good or bad for the economy. From at least one perspective, however, if we insert government regulation into our Monopolis Monopoly game, the result is a big surprise.

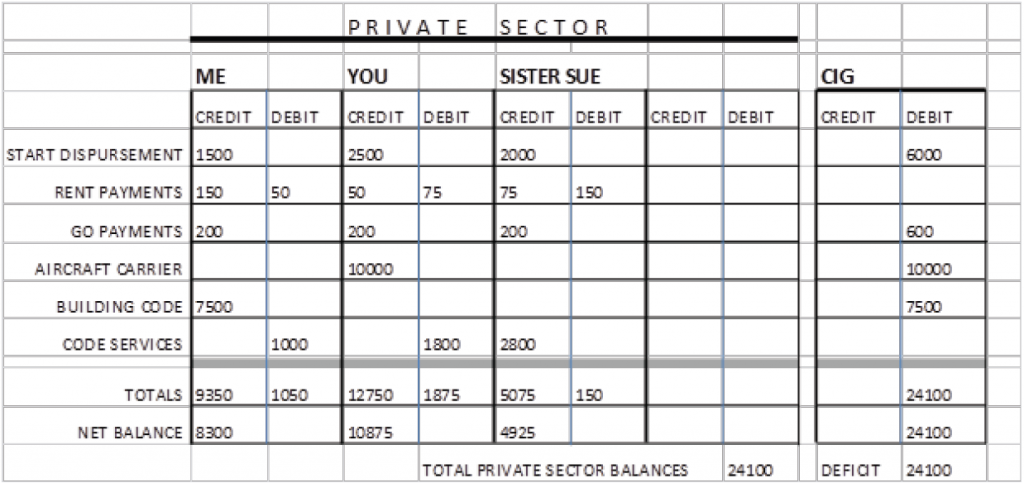

To see this, let’s create a regulation. Since our game involves the building of houses and hotels, let’s have our regulation be a Building Code. Not just any Building Code, but a big, thick, extremely complex and detailed one like the International Building Code adopted by virtually every city in the United States. Once in place, the rule stipulates that players cannot build a house or hotel without meeting the requirements of the Code.

How does the government create such a Code? In exactly the same way it acquires an aircraft carrier: it pays someone to figure out what should be in the Code, pays them to write it, to illustrate it, to publish it. I would venture to guess that the International Building Code likely cost almost as much as an aircraft carrier, so I volunteer myself to be the player the government pays to write it. After I deliver the hefty volume, CIG transfers $7,500 into my currency account.

What we should notice here is that, like the aircraft carrier, the writing of the Building Code has injected a major sum of currency into the game. But something else has happened as well: The Building Code gives rise to a multitude of “services” which the game players now need, and which they can buy with their money. These are the services of professional experts who are trained to understand the Building Code (which is completely incomprehensible to those of ordinary intelligence). In our game, I have volunteered sister Sue to be the provider of Code Services to the other players. As can be seen on the Balance Sheet, both Me and You have paid Sister Sue for some of these services, and will continue to do so each time we add a house to one of our properties.

Unlike the aircraft carrier, then, the Building Code injects currency into the game and creates new things for the players to spend their money on. This particular government regulation, then, actually expands the economy of our game. This also is worth thinking about.

Enabling Structures

The sun’s been down an hour now, and the room we’re playing Monopolis Monopoly in has gotten pretty dark. Sister Sue turns on a light and—to our great surprise—we find we’re not alone! While we’ve been busy rolling the dice, clomping our tokens around the Monopoly board, and counting our stashes of currency, the neighbors have come over. They’re standing around, leaning against the walls, watching us with keen interest. They’re noticing all our pretty houses and hotels and colorful money, and I can tell from the expression on their faces that they want to join in the fun.

Fine with me, except there’s a problem: You and Me and sister Sue already own all the property on the Monopoly board. If the neighbors join the game there won’t be any property for them to buy, and without property, they couldn’t work with You to build a house, or hire Me to design one, or sister Sue to interpret the Building Code. So there’s really no way they can participate in the game.

But a couple of these folks are leaning forward now in a determined way, hands pushed in their pockets in a manner that suggests they might be coming out of their pockets at any moment, and I’m starting to get worried. There are a couple of kids, hanging onto their mother’s dress, who look like they haven’t eaten in two or three days. Sister Sue is looking at them and getting tearful.

Suddenly, I’m struck by a lightning bolt idea, and I immediately share it with the other players: The government of Monopolis should build a series of structures on the Monopoly board that creates new properties that players can build more houses and hotels on. I suggest calling them “Enabling Structures” because they will enable the neighbors to participate in the game. I quickly design a prototype:

The path of play around the board will now zig-up through the Enabling Structure and zag-down to the lower board, with the players either claiming possession of or paying rent to the owners of the Enabling Structure Lots.

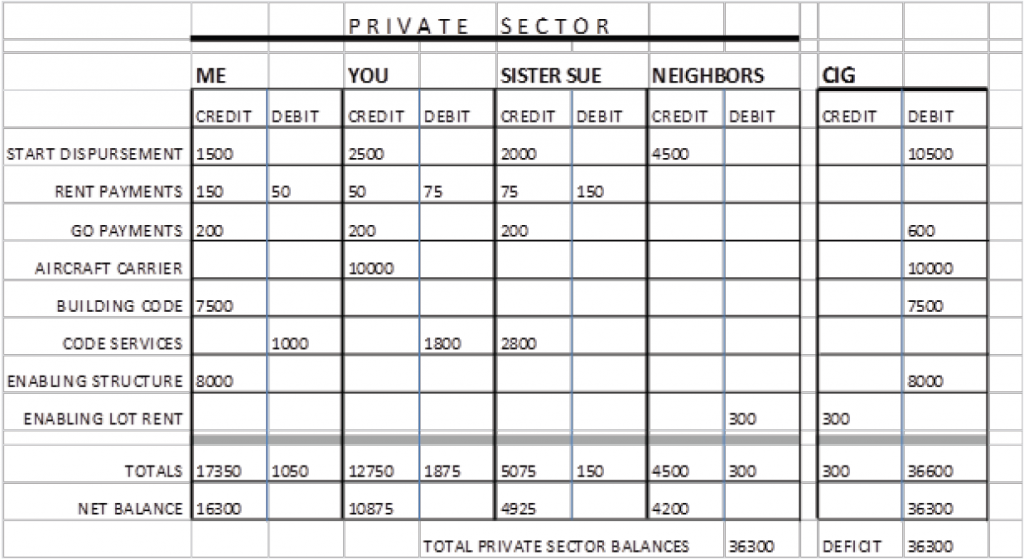

How will the government build the Enabling Structures? Just like it buys an aircraft carrier or a building code, and I nominate myself (it was my idea, after all) to be the Enabling Structure developer. I build them all around the monopoly board, effectively doubling the number of properties and houses and hotels players can now buy in the game. To compensate my efforts, CIG injects the tidy sum of $8,000 into my currency account.

Now the neighbors can join the game, except they still don’t have any money to begin playing with—the same dilemma, recall, we started out with ourselves. Sister Sue proposes that our currency issuing government is perfectly capable of paying each of the neighbors to build a house on the first “Enabling Lot” they land on, and this procurement by our Monopolis government will become their “start-up” cash for playing the game. The new player will then pay “rent” back to CIG each time they pass go, until those payments equal the original procurement, at which point they will own the houses outright.

Whew! Now the neighbors are in the game, and after a few rounds, they’ve acquired property and built some houses, and the game proceeds just as before, except now there are more of us playing. And while the building of the Enabling Structures—and the government’s procurement of the first Enabling Structure houses—has injected a big chunk of currency into the private sector, it’s also created a LOT more things for the players to buy and sell to each other: more properties, more houses, more building services, more design services, and more services to interpret the Building Code. That’s really something to think about.

Here’s where we need to pay close attention

As the neighbors get more deeply involved in the game, building houses, collecting rents, passing Go, our currency issuing government is going to quickly run out of the money that came in the Monopoly box. So, for our game to continue, we have to follow the Monopoly rules (already stated) which instruct the “banker” to get out pencil, paper, and scissors and begin creating more currency to keep up with the expanding needs of the game.

Now there may be some folks at the table who are genuinely alarmed by this idea. They may tell us that the government cannot just “print money” because that will inevitably lead to hyper-inflation; that the government, just like all the rest of us, must “live within its means.” Their heated arguments might persuade other players too, because, well…it’s just obvious that “printing money” and running up the sovereign “deficit” is the road to serfdom.

The question is, should we listen to them? Let’s update our Balance Sheet and see what we think. (To keep the Balance Sheet fitted on the page, I’ve combined the neighbors transactions into a single column; I’ve assumed there are three of them, that they’ve each claimed an Enabling Structure lot, that CIG has paid each of them $1500 to build a house on that property, and they’ve each made one rent payment of $100 back to CIG.)

It’s clear, looking at the Balance Sheet that our CIG continues to run a “deficit”. It is also clear (especially since the neighbors joined the game) that this deficit has been growing at an increasing rate. But in what sense does that deficit become a “debt” that we, the players, should worry about paying back? The balance sheet shows that the CIG’s deficit is not our debt at all, but simply a record of the currency that’s been issued into our game. And where did all that “deficit spending” end up? Look again at the balance sheet: it’s in the accounts and assets of the players themselves.

Maybe we should think of something else to call it

When my personal bank account is in “deficit”, that is something I worry about. When a city or state government has a “deficit”, that’s also something to worry about because we have not given our “local” governments the power to issue the currency (they are users of the currency, just like the rest of the players.) When their coffers are empty, they have to make tough choices and cutback on their spending. But when we say our sovereign government has a growing “deficit”, we are badly misleading ourselves if we use the word the way we do when we think of our own bank accounts. What Monopolis Monopoly is showing us is that our sovereign “deficit” is in fact a balance sheet accounting of our own financial wealth. And why we would want to reduce that is a mysterious thing indeed!

MMT versus Neanderthal Economics

Actually, there’s only one reason we’d want to make ourselves miserable by imposing some arbitrary budget rule or fiscal austerity on our game: because we still believe we’re operating under the rules of what might now be called “Neanderthal Economics,” which go something like this:

“We must adhere to the principles of ‘sound money’ for if we do not, our citizens will lose faith in the currency and begin converting it into gold. To prevent this from happening, the sovereign must spend only what it takes in. If it tries to spend too much, its gold reserves will be depleted and it will be forced into bankruptcy just like anyone else.”

And what if, believing this, we actually eliminated the deficit and began running surpluses? Well, in that case it’s obvious our game of Monopolis Monopoly would quickly come to an end: Our CIG would have all its money again, but the players would have nothing with which to play the game. At that point, we might just as well pack everything neatly into the Monopoly box and put it back on the pantry shelf.

The astute player will object that we’ve left out too many things for our game to really mean anything: Private banking, for example, or managing inflation, or bonds and interest rates (if the Fed doesn’t “need” money, then why does it seem to borrow so much of it?) Next time we play Monopolis we could add those in, but they won’t change the basic MMT truths that our simple version of the game has revealed:

A society with a sovereign fiat currency can build any thing or obtain any service it deems necessary or desirable, so long as the citizens of that society are willing and able to build the thing, or provide the service, in exchange for the fiat money. The sovereign deficit, no matter how large it may grow, is not like a shortfall in your own bank account: it is the balance sheet record of the

money that was transferred to our side of the ledger.

The implications of this, I believe, are simply astounding.

J.D. ALT 5-16-12

This is a continuation of ideas first developed in my novel, The Architect Who Couldn’t Sing, (available at Amazon.com or iBooks.) It was prompted by an article in The Washington Post, 18 February 2012, by Dylan Matthews, Modern Monetary Theory, an unconventional take on economic strategy, and was subsequently informed by the writings of L. Randall Wray (Understanding Modern Money, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited) and the writing of Stephanie Kelton, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Pingback: And You Thought You Knew Monopoly - Market Remarks

Pingback: J. D. Alt: Playing Monopolis Monopoly: An inquiry into why we are making ourselves so miserable « naked capitalism

Pingback: The (Semantic) Problem with MMT: An Exercise in Framing | | New Economic PerspectivesNew Economic Perspectives

Pingback: Utiliser les règles du Monopoly pour commencer à expliquer le fonctionnement des…

Pingback: Anonymous: The Fable of “Moral Arithmetic” « naked capitalism

Pingback: The Biggest Tragedy In Economics « Money & Business

Pingback: Letter to My Brother - New Economic Perspectives

Pingback: MMT: Why the USA Is Not Broke | Mediaroots

Pingback: 2012 National eBOOK Award for Architecture goes to NEP blogger | New Economic Perspectives

Pingback: Fox News Follows California Beach Bum Living Off Food Stamps For Years - Page 7 - MyLesPaul.com