Steven Rattner’s opinion piece in the New York Times and Furman’s interview on National Public Radio are perfect examples of the ideas that MMT want to debunk. Deficits are not normal; deficits crowd out private investment; the public debt is a burden on our grandchildren; our ability to respond to societal problems is limited by the fact that the US government does not have enough money to confront them.

Below is an alternative interview to the Furman’s interview that reviews these points. This blog will run like a traditional interview and all the evidence for the points made are in appendices at the end (Dear Ms. Cornish, I hope you will forgive me but I will plagiarize you entirely for the sake of this exercise).

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

The national debt surpassed $22 trillion this week – a new record – and this despite candidate Donald Trump’s promise to reduce U.S. debt once he became president. There was a time when the soaring national debt caused panic in Washington. Now it’s mostly crickets, at least from the officials who have control over the federal budget. So what’s changed? We’re going to ask Eric Tymoigne. He is an associate professor of economics at Lewis & Clark College. His works shows that one must make a crucial distinction between monetarily sovereign and non-monetarily sovereign governments when discussing issues surrounding the public debt and fiscal deficits.

Welcome to the program.

ERIC TYMOIGNE: Thanks for having me.

CORNISH: So you’ve written about the debt. And you hear that $22 trillion figure, and you argue that it’s not so scary. How come?

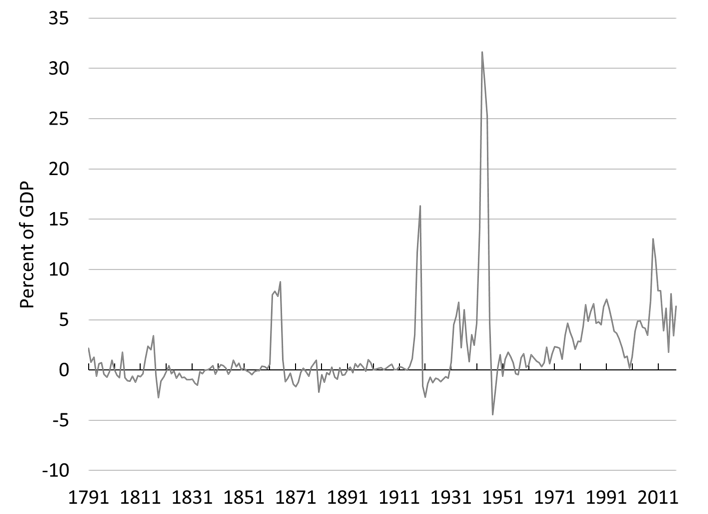

TYMOIGNE: Let me give you a bit of context. The public debt is the sum of all IOUs owed by the US Treasury; it can be measured as gross debt (all outstanding IOUs owed by the Treasury) or net debt (it excludes Treasury IOUs that other federal agencies holds). $22 trillion is the outstanding gross public debt. Until the 1930s, gross public debt fell more often than it rose and only major wars caused rapid increases in the public debt. While the public debt decreased more often than it grew, overall the public debt did grow slowly because increases were on average larger. Since the Great Depression, the public debt has increased almost continuously (Appendix 1).

Regarding the context of your question, I don’t think anything has changed in terms of the hysteria surrounding the public debt. Since 1789, when the US Treasury was established, pundits, journalists, Treasury officials, and/or politicians, among others, have all sounded the alarm about the threats posed by a growing public debt. This interview is just the latest example of such daily mass hysteria. Yes, politicians are currently less vocal about it, but many others have taken their place.

This hysteria has been so strong that it has led to inaction, or inadequate responses, to the problem of our times. Politicians are so focused on the debt number that they lose sight of the issues at hand. For example, the misplaced fear about the upcoming insolvency of the social security system has reduced our leaders’ ability to response to the challenges of an aging society. Only the will to go to war provides strong enough of a motive to leave the debt concern aside. In the mind of our political leaders, worries about climate change, poverty, unemployment, healthcare, childcare or any other socio-economic issue have always been secondary to worries about the public debt.

Regarding your question, there are several reasons why one needs not to be fixated on, and worried about, the size of the public debt.

First, Treasury securities (one type of IOUs included in the public debt) provide to the non-federal sectors (such as households, firms, pension funds, state governments and foreigners) a means to accumulate financial wealth in a safe way. Treasury securities are also the backbone of the financial system. They serve as safe collateral and are a crucial means to meet the requirements of financial regulations.

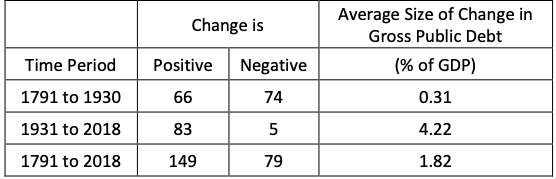

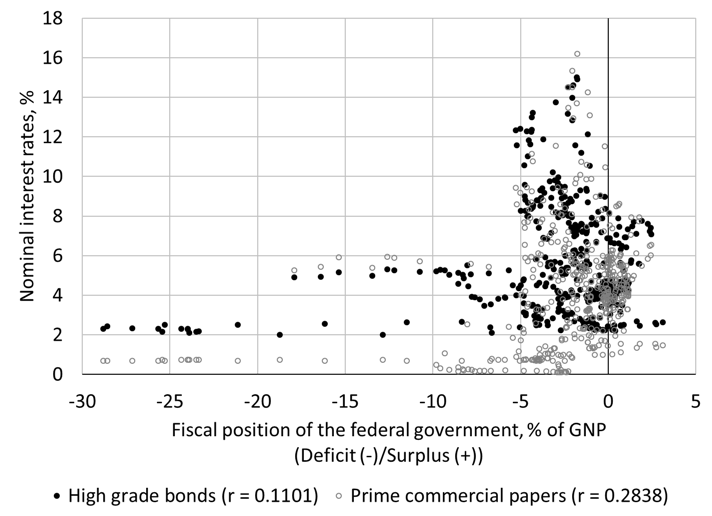

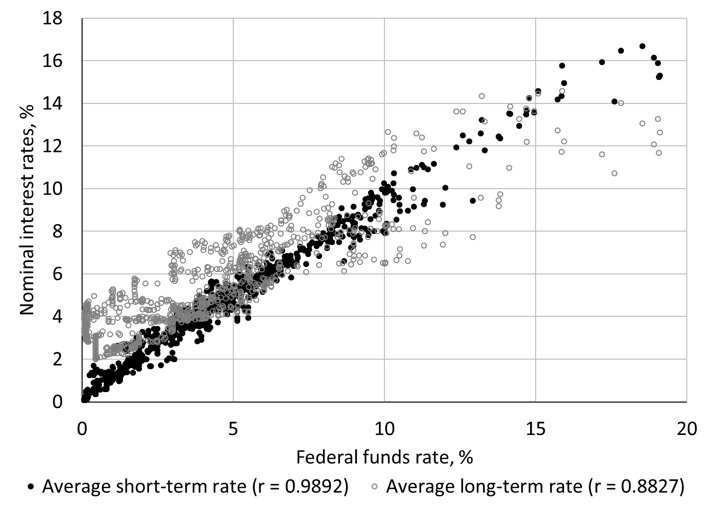

Second, one should worry about the public debt only if it negatively influenced economic variables such as economic growth, inflation, tax rates, or interest rates. The evidence of that are scant despite the broken records continuously played by those who promote hysteria about the public debt. For example, some argues that the current situation is special because we have a high public debt and low interest rate; this situation is the norm. There is no relationship between the fiscal position (deficit, balanced budget or surplus) of the US government and interest rates, none. Interest rates are not driven by fiscal policy matters. They are driven almost entirely by the monetary policy of the Federal Reserve (Appendix 2). The crowding out does not exist.

In terms of economic growth, the greater involvement of the US government in the economy has not generated a decline in economic growth. However, the greater involvement of the government has considerably reduced the volatility of economic growth by sustaining the income of the private sector. The economy has recorded fewer contractions; contractions have been much milder, much less lengthy, and more spaced (Appendix 3).

In terms of tax rates, the public debt will never be repaid. We have not been burdened with higher tax rates to repay the public debt created at the time of our grandparents; our children and grandchildren won’t be burdened by higher tax rates to repay the public debt created today. We may raise tax rates in the future but not with the goal of repaying the public debt. There is no reason to do so, and doing so would be harmful to the finances of households, banks, firms and other for the reasons I just provided.

The public debt will keep piling up to accommodate the needs of our growing economy and the US government will keep paying it on time. The US government does not, has never, and ought not to, manage the public debt in the same way you and I manage our private debts. It is incorrect to analyze the finances of the US government by taking household or business finances as a point of reference. Public and private debts are totally different animals when a monetarily sovereign government is involved.

CORNISH: To you, what has changed? What’s different?

TYMOIGNE. Nothing has changed. As usual, fiscal deficits (government spending larger than taxes) are a boost to the saving of the domestic private sector, state and local governments, and the rest of the world. In the short run, deficits sustain private incomes by injecting more money in the economy than they remove through taxes. Deficits help to sustain private investment by stabilizing the profit of businesses. Expected sales, not interest rates, are the main driver of business investment and fiscal deficits boost the sales of businesses while having a negligible impact on the cost of credit. In the long run, deficits translate into the public debt that provides a reliable source of net wealth to non-federal sectors as I just explained.

If I had to cite one issue that I have regarding the public debt, it is with regard to the change in the structure of ownership of the public debt. On one side, foreign holders have owned a growing proportion of the public debt since the 1970s; mostly via ownership through foreign central banks, foreign Treasuries, and other official institutions. This reflects the growing role of the US dollar in the international economy. On the other side, households and non-financial companies have recorded a major decline in their share of ownership of the public debt.

The worry here is not that the US Treasury is more and more dependent on foreigners to finance its expenses; it is not. Instead, the US Treasury does foreigners a favor by being willing to exchange their non-interest earning dollars into interest-earning dollars. The worry is that this change of ownership has reoriented the interest payments on the public debt away from the domestic economy, where it boosts private income, toward the rest of the world. This unfortunate change creates a drag on economic growth and the growth of domestic private wealth (Appendix 4).

CORNISH: But as you’re talking about, I mean, the economy is good. Unemployment is low. If there was ever a time when we should be shrinking the national deficit, shouldn’t this be it? I mean, is this the time for some dramatic moves?

TYMOIGNE. The main reason the US Treasury runs a deficit is not deliberate reckless policies or politicians who do not know how to put the US government finances in order. The US government actually has little control over the size of its expenditures and revenues.

Tax revenues are heavily influenced by the income earned by the domestic private sector and this fluctuates widely with the business cycle. For a given tax structure, that sets the tax rate on each income level, the US Treasury is highly dependent on the vagaries of the economy for its tax revenues. In an economic expansion, tax revenues rise quickly because private sector income rises. In a recession, tax revenues fall quickly because private sector income falls. In terms of government expenditures, a large portion of them is set by legal requirements (social security, Medicare, etc.) (Appendix 5).

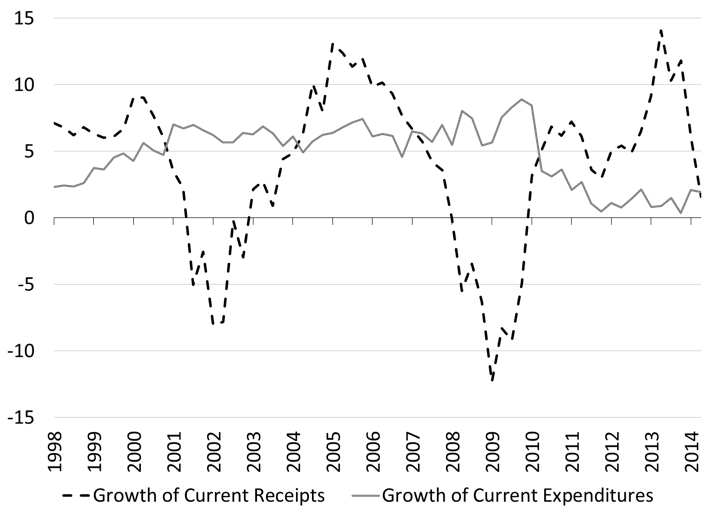

Of course, this begs the question of what, if not the US government, determines the size of the fiscal position and so the growth of the public debt. The main drivers are the desire of other economic sectors to accumulate financial wealth. Deficits inject income in the domestic private sector and the foreign sector. Usually these sectors desire to save some of that extra income. They desire to do so because it provides them financial flexibility and because they have retirement needs, educational needs, among others.

At the macroeconomic level, not all economic sectors can record a surplus at the same time, at least one of them must be in deficit for the others to be in surplus. There is actually a macroeconomic accounting identity that shows this, but I won’t go into it in this interview. The central implication of that accounting identity is that at least the domestic private sector, or the government sector, or the foreign sector must be in deficit if one of the other sector is in surplus. In the case of the United States, the domestic private sector and the foreign sector want a surplus. They record a surplus; therefore, the government sector must record a deficit (Appendix 6).

In other words, fiscal deficits are a normal state of affairs for the US government. They have been so for decades. This is the norm in the United States and throughout the world. Get over it.

So no, the government should not proactively try to reduce its fiscal deficit and repay its public debt. The government should let it fiscal positions be whatever it needs to be in order to accommodate the desires of the other sectors to improve their financial standing. Going against the desired surplus of the non-government sectors will only result in a recession.

CORNISH: The new tax law has been in effect for a little over a year now. Are we actually moving in that direction?

TYMOIGNE. Again, the fiscal position will adjust to the needs of the economy. We should forget altogether about the fiscal position and the public debt and pay attention to the real issues. In that case, the tax law was a major issue in the sense that it has provided massive permanent tax breaks to income categories that do not need them. In that sense, we are moving in the wrong direction because we are reinforcing income and wealth inequalities that are already extremely high. The new tax law perpetuates and encourages the rise of dynasties that already have overwhelming influences on our socio-eco-political life.

CORNISH: If the national debt is an indicator of long-term economic health, then why wouldn’t we be worried?

TYMOIGNE. The national debt is not an indicator of our long-term economic health. The public debt can always be repaid. Analysts who acknowledge that the US government is monetarily sovereign have long understood that there is zero probability of default on the public debt (Appendix 7). The US government cannot be forced to default on its public debt.

This, of course, does not mean that we ought to repay the debt at once by “printing money”; this is a silly conclusion. That would be massively inflationary and I already stated that it is in nobody’s interest to repay the public debt and we won’t.

What monetary sovereignty means is that the US government has control over the cost of its public debt, that it can decide what type of debt to offer to other sectors, and that government has the financial flexibility to spend on whatever its society decided is the public purpose. The government is not dependent on China’s willingness to purchase US Treasuries, and bond vigilantes don’t dictate the cost of debt (Appendix 2).

The public debt is not managed like a private debt. Its growth and structure (proportion of short-term IOUs vs long-term IOUs) are managed to accommodate the needs of the economy rather than to prevent bankruptcy. If other sectors want to hold more public debt, the US government issues more. If other sectors want more long-term securities instead of short-term securities, the US government accommodates even if the interest rate is higher. If other sectors want to hold less public debt, the US government fiscal position turns into a surplus. For example, if foreigners decide they do not want to hold US dollars assets, they can try to dump them quickly (which would negatively impact them) or they can start buying more goods and services from the US than they sell to the US. In the second case, the US government fiscal position will move toward a surplus in order to accommodate the will of the foreign sector to be in deficit with the US. A few countries, mostly in Scandinavia recently, are in a similar situation. This is an unusual case.

As long as the cost of public debt stays low relative to the growth of the economy, the public debt will not explode relative to the size of the economy. The usual case is that the interest rate on the public debt is below the growth rate of the economy, precisely because a monetarily sovereign government has a strong control over that interest rate. Olivier Blanchard recently received a lot of attention for making that point, but it has been made for a long time by other economists such as, for example, Scott Fullwiler.

What are indicators of health for our economy? Standard of living, life expectancy, literacy rate, availability and quality of childcare and healthcare, are major indicators. Low unemployment, moderate income and wealth inequalities that encourage individual initiatives, quality infrastructures that accommodate the needs of the society, and environmental sustainability are others. We are failing on a number of these indicators of economic health. Take a look at the crumbling state of our infrastructures that requires trillions of dollars to be brought back up to standard.

Today the greatest threat is environmental sustainability, not only in terms of climate change, but also in terms of the sustainability of our consumption-oriented society. This problem is so large that it directly threatens human existence. Since the 1970s at least, species have been dying left and right at an accelerating rate; environmental systems are collapsing rapidly; and yet very little is done. A Green New Deal would be a good start but much more would be needed in the US and abroad. Responding effectively to these pressing issues will require massive government spending, and generate a rapid increase in the public debt, here and abroad. We did it during World War Two, we can do it again.

The question you have to ask yourself is if tackling these issues is more important than a number on a spreadsheet. While solving these issues may require sacrifice in terms of productive resources, especially if a rapid reengineering of our economy is required (which it is for some issues), it will not require a sacrifice in financial terms for the US government and our grandchildren. What is productively possible is always financially possible for a monetarily sovereign government. We may have to declare War on Climate Change for people to realize that.

CORNISH: Eric Tymoigne, associate professor of economics at Lewis & Clark College. Thank you for speaking with us.

TYMOIGNE: Thanks so much for having me.

Appendix 1. Change to Gross Public Debt relative to GDP: 1791-2018

Three major wars (War of 1812, Civil War and World War I) caused unusually rapid increases in the public debt, but otherwise the public debt grew slowing or declined. Since the Great Depression, the public debt has mostly gone up with only five recorded declines (1947-49, 1951, 1956-57). Major wars (World War Two, Vietnam War, War on Terror) have rapidly increased the public debt, but sizeable increases have become a permanent feature of the post-1920s period.

Figure 1. Change to Gross Public Debt relative to GDP: 1791-2018

Sources: Treasury Direct (https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt.htm), Government Info (https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BUDGET-2019-TAB/BUDGET-2019-TAB-8-1), Bureau of Economic Analysis (Nominal GDP).

Note: “Change to gross public debt to GDP” matches exactly absolute changes to gross public debt. Division by GDP does not influence the type of changes (Positive or Negative) in gross public debt but gives us a more readable graph.

Appendix 2: Monetary policy drives interest rates, not fiscal policy.

Figures 2 and 3 show that the fiscal position is unrelated to the cost of credit, while monetary policy has a very strong influence. When the US Treasury runs very large deficits, it usually does so in periods of recession when tax revenues plummet. During these periods, the Federal Reserve also lowers its policy interest rate to help the economy and all other rates follow. During World War II, when the fiscal deficit ran past 20% of GDP as government spending increased very rapidly, the Federal Reserve set interest rates on the public debt very low for years and all other private interest rates followed and stayed low for years.

Figure 2. Fiscal position and interest rates

Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research (Macrohistory Database, Tables from “The American Business Cycle”), Treasury Bulletin (via FRASER), Bureau of Fiscal Service (Monthly Receipts, Outlays, and Deficit or Surplus, Fiscal Years 1981-2017)

Note: Quarterly data, Q1 1880 to Q4 2016 for fiscal position and commercial paper, Q1 1900 to Q4 2016 for high-grade bonds.

Figure 3 Monetary policy and nominal interest rates

Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research (Macrohistory Database)

Note: Monthly data from January 1919 to December 2015

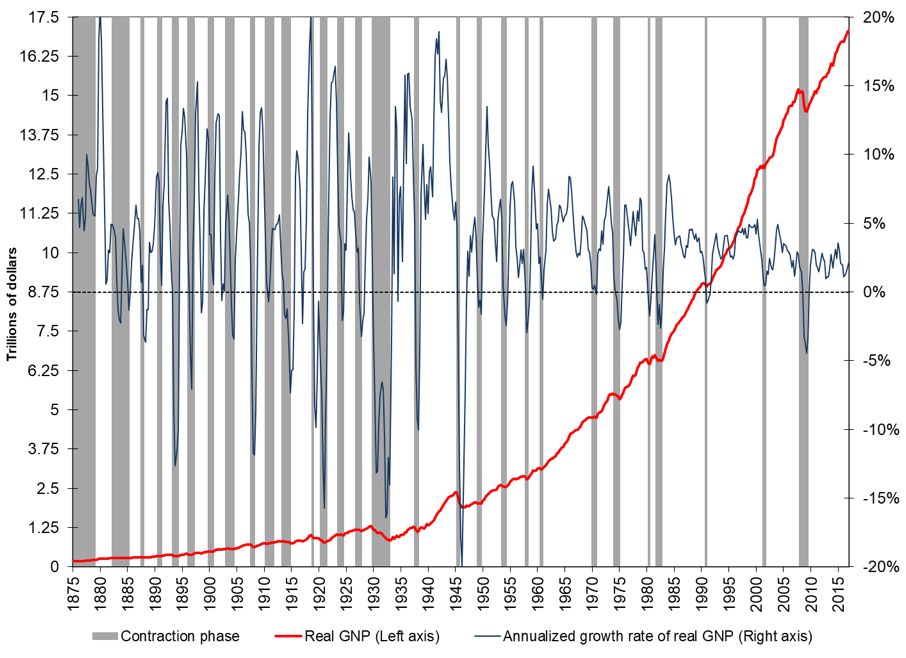

Appendix 3: Big government and economic stability

Figure 4 shows that the growth rate of gross national product (GNP) is the same prior to, and after, World War Two. The volatility of the growth rate of GNP has declined significantly after World War Two (the blue line fluctuates much less). There also are less contractions (grey bars), and they are thinner and more spaced out. When there is a recession, GNP falls less and recovers faster.

Figure 4. The U.S. Business Cycle: 1875:1-2017:1 (Base: 2009)

Sources: NBER, BEA, The American Business Cycle by R.J. Gordon (ed.).

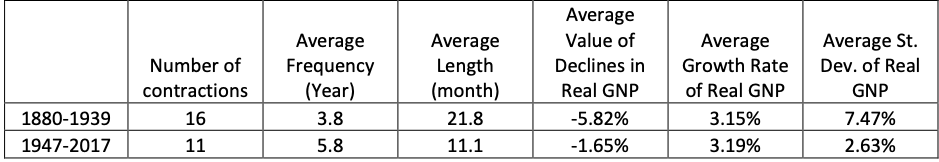

Appendix 4: Ownership of the Gross Public Debt

The share of public debt held by the domestic private nonfinancial sector has shrunk from 40% of the public debt to 5%. Meanwhile the share held by the rest of the world, especially official institutions, has grown tremendously.

Figure 4. Structure of Ownership of Gross Public Debt, 1945-2013.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

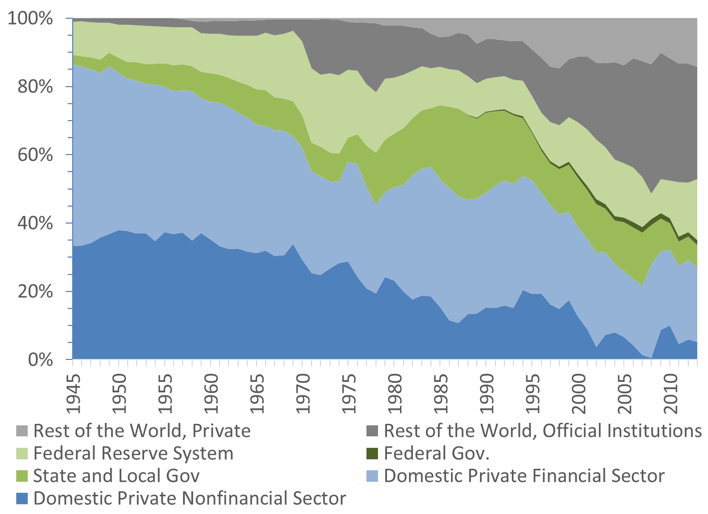

Appendix 5. Revenues and expenditures by the federal government move automatically, tax revenues move very widely.

Figure 5. Growth rate of taxes and other dues, and growth rate of federal expenditures, percent

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

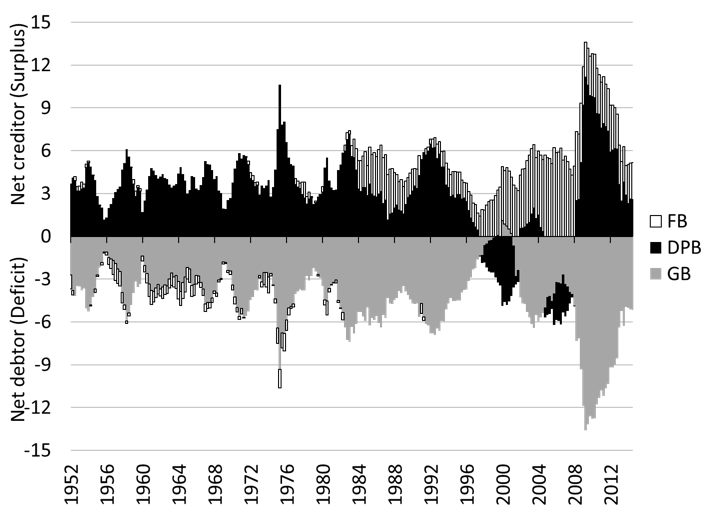

Appendix 6: Not all sectors can record a surplus at the same time.

Figure 6 illustrates the point by showing the financial balance (Surplus (+) or deficit (-)) of the three major sectors of the economy. In accounting terms, we know that:

Government balance + Domestic private sector balance + Foreign balance = 0

This applies at all times. Usually the government sector runs a deficit and the other sectors record a surplus. We had an unusual period in the late 1990s and mid 2000s when the domestic private sector balance (the black area in the graph) was negative and the government sector briefly recorded a small surplus (Democrats were so proud of this although their fiscal policy pushed the domestic private sector balance further and further in the red). This ultimately led to the Great Recession because, contrary to the US government, the domestic private sector cannot sustain a deficit.

Figure 6. Financial Balance (+ surplus, – deficit) of the Foreign sector (F), domestic private sector (DP) and government (G)

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Appendix 7: The US government is always able to pay its debt as long as it is denominated in USD

7 responses to ““What You Need To Know About The $22 Trillion National Debt”: The Alternative Interview”