By J.D. ALT

Even if we assume the principles of modern fiat money will be generally accepted at some point in the future, we must yet confront the problem that sovereign spending is a difficult issue for market economies. It could easily unfold that even with the new “modern” money perspective in place, a serious recession could still find federal stimulus spending unnecessarily constrained. This difficulty was on full display in the last recession when Obama’s stimulus package was finally passed by Congress—appropriating $800 billion for the federal government to spend—only to then confront the almost burlesque-show entertainment of watching Congress and the Obama administration trying to figure out how to actually do the spending.

The issue, of course, is that in what is supposed to be a sacrosanct market economy there are only three arenas (that I can think of at the moment) where direct sovereign spending to buy goods and services from the private sector is considered justified or allowable:

- National Defense and Security—because it is generally acknowledged there is a powerful need for highly centralized planning, control, and implementation.

- Basic Science Research—because there is general agreement that, while basic research can greatly benefit both the collective good and private industry, private industry itself will not engage in such spending because the risks of financial loss are too high and the chances of financial gain too small.

- Collective Goods and Services Which Significantly Benefit the General Public—because it is generally agreed that while such collective goods and services are desirable and in many cases necessary, it is unlikely that market-based private industry will provide them because of their lack of profitability.

If the sovereign government proposes to buy goods and services outside these three arenas, private industry will complain mightily that the sovereign is interfering in the free market by “picking winners” or, even worse, directly competing with private enterprise. A related problem is that sovereign spending within these three arenas—even if Congress appropriates new dollars to them—will do little to employ the vast majority of people who most desperately need to be employed. Under-educated people without specialized skills have fewer and fewer places to participate in the modern market economy. As a consequence, it seems they are of necessity driven instead to shadow economies. (One of the few entrepreneurial opportunities available to people marginalized by the “official” market economy is growing marijuana.)

The difficulty of sovereign spending in a market-based ideology is embodied in the idea that if a stimulus is needed, the only market-based option allowed is for the central bank to push down interest rates. The thinking seems to be that, unless the market itself can motivate private enterprise to borrow capital and hire workers, it is better that nothing should happen at all, lest we slide down a slippery slope into a socialist command economy. This is why the U.S. central bank is so nervous at the present moment about not being able to push interest rates back up from their near zero levels—out of fear that if the economy slides back into recession (which it feels like it could easily do) the single tool the market-based ideology gives the federal government to play with is essentially inoperable.

From the perspective of modern fiat money this obsession with interest-rate stimulus makes no sense. If the market is unable to incentivize private industry to hire people to create the goods and services society needs, the idea that the only alternative available is a socialist solution imposed by Big Government and higher taxes is simply a false choice. Once you accept that the federal government is not spending either tax dollars or borrowed dollars, it is entirely possible, for example, to imagine sovereign spending programs which are not envisioned, managed, or implemented by the central government at all. It is also possible to imagine sovereign spending programs that not only produce real goods and services society needs, but actually strengthen and diversify the market economy itself—creating employment and even entrepreneurial opportunities for marginalized people in the process.

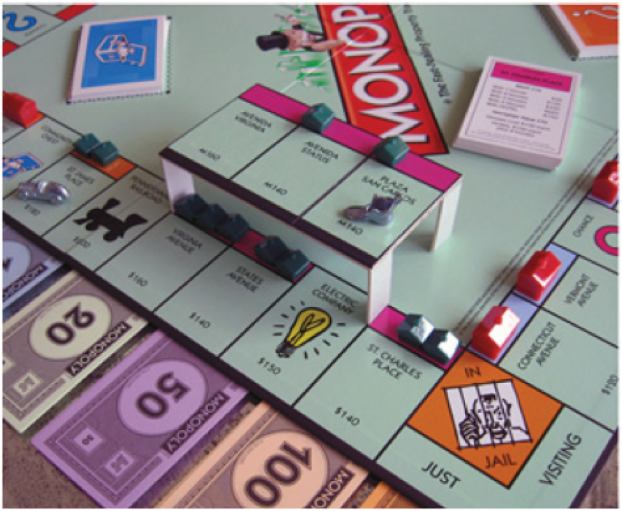

The general model I keep tinkering with is the same one I introduced in the very first NEP essay I wrote, “Playing Monopoly Monopolis.” Here’s how I described in then:

The sun’s been down an hour now, and the room we’re playing Monopolis Monopoly in has gotten pretty dark. Sister Sue turns on a light and—to our great surprise—we find we’re not alone! While we’ve been busy rolling the dice, clomping our tokens around the Monopoly board, and counting our stashes of currency, the neighbors have come over. They’re standing around, leaning against the walls, watching us with keen interest. They’re noticing all our pretty houses and hotels and colorful money, and I can tell from the expression on their faces that they want to join in the fun.

Fine with me, except there’s a problem: You and Me and sister Sue already own all the property on the Monopoly board. If the neighbors join the game there won’t be any property for them to buy, and without property, they couldn’t work with You to build a house, or hire Me to design one, or sister Sue to interpret the Building Code. So there’s really no way they can participate in the game.

But a couple of these folks are leaning forward now in a determined way, hands pushed in their pockets in a manner that suggests they might be coming out of their pockets at any moment, and I’m starting to get worried. There are a couple of kids, hanging onto their mother’s dress, who look like they haven’t eaten in two or three days. Sister Sue is looking at them and getting tearful.

Suddenly, I’m struck by a lightning bolt idea, and I immediately share it with the other players: The government of Monopolis should build a series of structures on the Monopoly board that creates new properties that players can build more houses and hotels on. I suggest calling them “Enabling Structures” because they will enable the neighbors to participate in the game. I quickly design a prototype:

The path of play around the board will now zig-up through the Enabling Structure and zag-down to the lower board, with the players either claiming possession of or paying rent to the owners of the Enabling Structure Lots.

How will the government build the Enabling Structures? Just like it buys an aircraft carrier or a building code, and I nominate myself (it was my idea, after all) to be the Enabling Structure developer. I build them all around the monopoly board, effectively doubling the number of properties and houses and hotels players can now buy in the game. To compensate my efforts, CIG (currency issuing government) injects the tidy sum of $8,000 into my currency account.

Now the neighbors can join the game, except they still don’t have any money to begin playing with—the same dilemma, recall, we started out with ourselves. Sister Sue proposes that our currency issuing government is perfectly capable of paying each of the neighbors to build a house on the first “Enabling Lot” they land on, and this procurement by our Monopolis government will become their “start-up” cash for playing the game. The new player will then pay “rent” back to CIG each time they pass go, until those payments equal the original procurement, at which point they will own the houses outright.

Whew! Now the neighbors are in the game, and after a few rounds, they’ve acquired property and built some houses, and the game proceeds just as before, except now there are more of us playing. And while the building of the Enabling Structures—and the government’s procurement of the first Enabling Structure houses—has injected a big chunk of currency into the private sector, it’s also created a LOT more things for the players to buy and sell to each other: more properties, more houses, more building services, more design services, and more services to interpret the Building Code. That’s really something to think about.

In 2012, when I wrote the above, I was thinking particularly of Enabling Structures which are physical constructs, which are paid for by sovereign spending, and which then enable and support a subsequent small-business-market-based process building affordable houses. Interestingly, the Pritzker Prize has just been awarded to a Chilean architect, Alejandro Aravena, for his affordable housing concepts that come strikingly close to the Enabling Structure concept.

Half of each dwelling is intended to be completed with sweat equity by the occupant-owner—and is open to interpretation as to what that completion will entail. It is even possible to imagine, for example, that the empty half could be finished as a separate rental unit, providing income for the owner-builder. Or it could be completed as a small workshop for some kind of local production—or as a small store or cafe. In other words, what we are looking at here is not a displacement of the market economy, but the beginning of a new, local component of the market economy. Importantly, it is a new market component specifically structured for the participation of people who would otherwise be marginalized. And BIG government is not telling people what they have to build in their empty “slots.”

I have more recently come to realize that the idea of Enabling Structures doesn’t have to be limited to physical constructs. It is possible to imagine many different kinds of organizational and/or informational “structures” which could be paid for with sovereign spending and which would, subsequently, enable local citizens to more easily and effectively create and participate in local markets—markets that enable them to create goods and services they really need. This leads me to suggest it might be well worthwhile to begin considering and documenting specific ideas about how direct sovereign spending could make this happen.

My idea is this: if we did what I just suggested, then, when the next recession hits—and the central bank finds that its traditional strategy of lowering interest rates is still not available (which is likely to be the case) and Congress is thus forced—against all its entrenched phobias and market ideologies—to appropriate another huge chunk of emergency sovereign spending, we’ll have a long list of ideas about how those new dollars can be spent to rapidly put them exactly where they most need to go. And once we’ve experienced how well that works, once we see that sovereign spending can expand the market economy rather than destroy it, we’ll have made a big step toward a general acceptance of, and appreciation for, the realities of modern fiat money.

26 responses to “Sovereign Spending in a Market Economy”