If you might want or need something to happen very badly or urgently that was debatably in your power to influence or effect, the chief rational approach you might choose would be to attempt to understand what are the causal forces or conditions that lead that thing to happen. The alternatives are forms of magical thinking or prayer to assumed-to-be more powerful, perhaps supernatural, beings. As the domain of effective and timely action on climate is largely within the domain of human beings’ ability to choose and influence others’ choices and such action is considered by increasing numbers of people to be highly desirable, one would think that substantial groups of social scientists would be making their best efforts to figure out how to “make climate action happen”. Even if you were not an intense partisan of a particular outcome, as the scenario above suggests, if you were just a scientist or seeker of knowledge of some type, you would also want to understand motive forces, so as to predict future outcomes and make your scientific knowledge of some use to human beings. This is the study of dynamics, how things change over time.

Of course, some of the causes of climate action, unfortunately, are related to what we cannot directly and specifically control, i.e. the sequence and timing of unusual weather and other semi-natural events and changes on a scale of months and years. How hot, dry, wet or “unnatural” any of these physical climate-related events/disasters will appear to people will definitely have a catalytic effect on societies and governments now still embracing half-measures or avoiding action all together. It is extremely unfortunate that some of the impetus for effective action will come from events that will already be signs of a climate system on a path to perhaps irreversible instability and hostility to human life. However we cannot count on the destabilized climate system to catalyze the right or proper actions: mounting climate disasters could lead to a focus purely on rearguard adaptation or to the embrace of faulty ideas that will not yield decisive and rapid emissions reductions. As with the Kyoto Protocol’s cap and trade system, half-measures can create their own set of entrenched interest groups invested in climate action as window-dressing rather than effective action itself. It still would be required that human beings make up their minds and act either before or after such disasters in a way that reduces their likelihood in the future, including fights with interest groups invested both in the status quo and in faulty ideas about what can spur emissions reductions.

The causes of “rapid, decisive” climate action, no matter the timing and severity of climate events, then lie exclusively within the arena of human agency and will. The formal, secular paradigms for trying to understand the vicissitudes of human agency and often originate in the social sciences and humanities or will be drawn into those and formalized from practical experience. Various religious teachings deal with human agency and will, but religious teachings tend to exclude non-believers and believers in other faiths from an area in which all humanity should be able to meet and discuss our common future.

It is unfortunate that the social sciences, the fields of study which might elucidate social and individual forces as regards climate action, are in quite a bit of disarray when it comes to analyzing the dynamics of the systems they are trying to study. Social scientists are often beholden to or working within interpretive frameworks that simplify society and the human being for the purpose of either promoting their own form of expert knowledge or applying that knowledge to some social need or problem. The end result is often a fairly static or flattened picture of how society or individuals function, think or behave, i.e. little or no realistic dynamics are represented.

The dominant social science framework of the last three decades has been the rather long-in-the-tooth neoclassical economic framework that originated in the late 19th Century and has been occasionally revised or reinforced over the intervening period. Neoclassical economics has a highly abstract yet simplified model of the human being that assumes that human beings and business organizations “maximize utility”. Furthermore it also assumes that market social systems which it also assumes to be the natural state of affairs of all of society, tend towards an equilibrium point. The latter assumption means that there are no complex or realistic dynamics to speak of in neoclassical models or explanations of economic systems. The all-encompassing market tends towards equilibrium and stays there, leading to scant explanations or guidance with regard to how real-world economic development happens or for that matter what policy interventions might yield better or different forms of economic development.

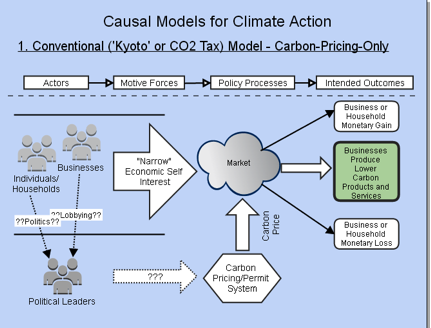

(Narrow) Self Interest is the Default Motivation in Climate Policy to Date

Within social scientific works or social policy frameworks based on neoclassical economics, there is the background assumption that all social dynamics, be they considered economic, political, cultural or psychological, are driven by self-interest, and furthermore a self-interest that seeks to maximize its gains (i.e. “utility”). The assumed self of neoclassical-economics-influenced social sciences corresponds then suspiciously to the ideal-type, not necessarily the reality, of a capitalist that tries to maximize monetary gains and minimize monetary losses. In political science we have neoclassical-economics-based public-choice theory which assumes that political actors are acting in their narrow self-interests, maximizing their individual “utilities” via various political actions. In the “law and economics” movement in legal education, “economics” is taken to mean a neoclassical approach to the economy that, of course, misrecognizes the role of government (constituted by a body of laws) in the economy.

In the world surrounding academia, in practical politics and cultural discourse more generally, we have the all-pervasive neoliberal ideology, based on some of these academic traditions, which also celebrates market mechanisms and individual destiny over broadly shared social destinies. Neoliberalism also celebrates the entrepreneur as the archetype of social change, an individual who in its propaganda is portrayed as heroically imposing their vision on the world rather than creatively responding to society’s vicissitudes. What follows from this unrealistic picture of entrepreneurship is the idea that the sole economic policy that should be followed is “liberating” entrepreneurs to apply their unique creativities to change society. This overlooks the role of large organizations particularly government in creating the conditions for innovation and change. In reality under the cover of fulsome praise for entrepreneurship, neoliberal policies do not “do away with” government but refashion it as largely an aid to the enrichment of incumbent economic interests, through various privatization schemes.

Established climate policy debates have revolved around different types of carbon pricing, either carbon pollution permit caps with pollution permit trading or carbon taxes of various types. Both of these policy orientations assume that the primary motivation of human beings is economic self-interest: the future lower- or net-zero carbon emitting society will be shaped by the actions of market actors (businesses and consumers) trying to avoid paying the carbon price. As I have commented in a number of places, the carbon pricing framework does not direct government investment or planning but explicitly relies on market actors to “lead the charge”. With the sole exception of the mechanics of the tax or trading system, carbon pricing as the central climate policy reinforces the belief in the heroic entrepreneur as the spur for social change and innovation.

As government actors “stand outside” the carbon pricing framework, the framework itself does not explain or encompass the conditions for its own emergence or refinement as a policy. The motivations of government leaders and/or the public at large in imposing a price or carbon cap appear “deus ex machina”. They are set “outside” the carbon pricing system based on various valuations of the cost of carbon emissions or permissible amount of emissions that are determined politically in a way that can be variously presented as a technocratic and pseudo-objective calculation or as the perhaps noble but mystery-shrouded act of moral commitment by leaders. The dogmatic adherence to this (confused & internally incoherent) policy orientation has profound implications for the type of climate politics that is considered “serious”.

Restricting or condensing the ethical encounter with the welfare of future generations to a carbon price or the trading of carbon permits, flattens both current human capacities as well as the uncertainties and near-certainties of the future and the future development of our species. The metric of a price or, slightly different than the deeply flawed cap and trade instrument, a carbon budget may be necessary but they do not encapsulate nor does the self-interest-alone model contain the conditions by which one can arrive at them in a just and effective manner. Ultimately then, despite the pseudo-objectivity of a price or the rate of descent of a cap, which may be components of carbon policy, neither can explain how they might be instituted or the mechanics/dynamics of actually achieving their intended goals.

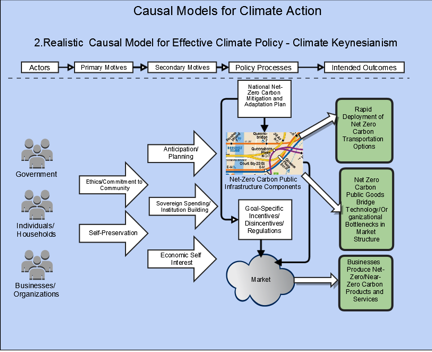

A Realistic Set of Motive Forces for Climate Action

While it may be attractive for thinkers to operate with a “monistic” theory of human motivation with a single causal force, the complex of social and individual motivations involved in human social life mean that realistically we must take into account a number.of motivations to get a sense of how climate action might take place. Below are a list of likely operative motive forces in determining the effectiveness and timeliness of climate policy.

1. Ethical Sense/Commitment to Community

A self-interest-only view of human beings is clearly inadequate to describe the various other-oriented interests and acts of human beings, along with their self-interested acts and impulses. Social and biological science theories of the last few decades often seem to surprisingly “forget” that humanity is a highly social species and that social institutions are not entirely reducible to the individuals that make them up. Human beings depend on some minimal integrity of social institutions and relationships to survive, a fact that is ignored by a monistic and atomistic self-interest-only view of humanity. While purely altruistic acts are not the norm, neither are grossly, narrowly self-interested acts. Therefore, the self-interest-only view of humanity is not even “hard-headedly” realistic as humans must depend on one another for their survival. Encoded currently into pedagogy and institutions, the self-interest-only view leads eventually to the corrosion of the bonds that humanity and human societies depend upon though luckily not the complete destruction of those bonds.

Action on climate change will involve a reinforcement and reliance upon humanity’s other-interest to a degree not seen perhaps in recorded history. A climate action movement that demands “in-time” climate action, will be motivated to a large degree by climate ethics. Furthermore government officials must experience similar motivations to impose climate laws and actions that rein in current consumption and emissions for the sake of future benefits to humanity. Ultimately effective climate action must involve present-day humanity encoding into laws, institutions and actions the interests of future generations to an extent that may co-equal or even predominate over the interests of the current generations. This collective act of imagining the future requires individuals to “make room for” those who haven’t yet been born. The emergent sum of these acts of foresight will become the basis for policy which may return again and again to ethical discussions regarding what might reasonably be the rights of those in the future upon the earth that we now inhabit.

Such a series of political-cultural-economic moves is a large cultural shift that will not be recognized in a model of human motivation that only sees humans as narrowly self-interested profit/utility maximizers.

2. Self-Preservation

While self-interest is much discussed, it is, I believe, analytically distinct from the impulse towards self-preservation. Self-interest, in the tradition of neoclassical economics, assumes that choices of “more” and “less” are laid out before the “utility maximizing” individual or actor. The choice is between more or less acquisition or loss of some possessions. A possible “trade-off” is always assumed, with the implication that that tradeoff will not usually have terminal effects on the person or persons involved.

More fundamental is the “either/or” question whether one lives or dies or whether the species lives or dies. I believe that this fundamental “either/or” regarding existence or non-existence needs to become more prominent in considerations of whether and how to act on climate change. It might be argued that self-preservation is the base-case or background anxiety behind self-interest but it is also qualitatively different (it is an “either-or” rather than a series of gradations of numerical value). Ultimately self-preservation will become a more prevalent factor as we see more social disruption due to climate or climate-related events. The “non-existence” condition is hard to place a value upon in monetary terms or in terms of a sliding scale of “utility”.

With increasing threats from climate catastrophes, people’s sense of preserving their own lives as well as those of their families will come more into play in driving climate policy decision making.

3. Anticipation/Planning

Ultimately human-caused climate change is a failure of planning on a grand scale: we have known that fossil fuels are finite for half a century and scientists have been warning us for 30 years that our fossil fuel use is changing the climate irreversibly. We have lived in a society that has emphasized seizing fleeting opportunities over planning: this has led to a chaotic style of life that is attractive to many of us but ultimately is leading us in its current extreme form, to neglect anticipating the consequences of our actions.

Anticipation is the basic human capacity that underlies our ability to plan, which has increasingly been upstaged by the needs of consumer society to emphasize immediate gratifications. Despite the pressures from advertising and media, the delay of gratifications is considered praiseworthy within the economic profession in the form of the saving of money. Professional economists, in some regards, could be viewed as being divided between those who praise the virtues of saving for individuals versus those who see the macroeconomic vices associated with saving and private wealth accumulation in both spurring inequality but also creating the pre-conditions for economic stagnation via shortfalls in economic demand. The lack of a clear and coherent directive from the profession overall with regard to the relationship of consumption, delay of consumption and economic well-being has been one of the great moral-intellectual stumbling blocks for policymakers.

We know with climate change that the impulse to plan will take on a new importance as the building of a new energy and transportation infrastructure rapidly will require more planning and more involved planning on a governmental as well as organizational levels for businesses and power utilities. Similarly, we need to be able to anticipate the likely or certain outcomes of our actions as individuals and consumers, which can be viewed as an outgrowth of ethical concern for others and for future generations. At the same time we will continue to need to manage monetary economies to prevent their collapse due to excessive monetary savings and shortfalls in demand.

4. Sovereign Spending/Institution Building

More subtle perhaps but crucially important are the institutional “affordances” and momentum built into modern monetary economies and governments for the expression of community values via government spending and institution-building. In some moralistic views of money, money is thought to be the nexus of evil or the baser impulses of humanity. However despite this popular discourse, money is widely used as a measure of value as well as a means by which people, organizations and governments are able to mobilize resources for their individual goods, organizational missions and the common good.

In the 140 year history of the modern welfare and interventionist state, government spending and institution-building more generally have come to express the operative values of a given society, or at least those as negotiated through a more or less representative political process. While some contend with considerable justification that social spending and moral values expressed through spending are the result of the clash of social movements with political elites, the operative outcome is that fiscal reality comes to reflect the outcome of that conflict between political actors, be they inside or outside official political institutions. The example often given is that conservative German Chancellor Bismarck did not institute socialized health insurance out of the goodness of his heart but because he was under pressure from the German worker’s movements. Nevertheless, under these pressures, a social contract and social expectations were created which endures to this day in Germany.

Currently there is a dominant neoliberal/right-wing political discourse, based on erroneous though still mainstream economic assumptions that sees government involvement in the economy, especially in support of the social welfare of ordinary people, as optional and a superficial layer. Current baseline assumptions then imply or state that government expenditures and institution building, especially for the purposes of broad social welfare rather than elite enrichment, are deviations from good practice. There is ample evidence showing that the growth and wealth that the political Right values or claims to value is a product of that spending and government involvement in the economy. Shortsightedly the neoliberal Right and their centrist allies attempt to kill “the goose that lays the golden eggs” and claim that their wealthy patrons laid or will at an indeterminate point in the future lay, the “golden eggs” instead. Those on the Right often believe that private organizations should replace government’s institution building but their thought and policy experiments seriously underestimate how government’s monopoly role in certain areas, like in basic support programs and currency issuance, is a huge benefit to society overall.

What a dispassionate look at the role of the fiscal institutions of governments reveals is that the ongoing process of civilization and the shaping of monetary value to reflect social values is seen in the budgeting decisions of governments in cross-national comparison. The expression of the “public purpose” via these spending decisions, yields national societies with particular shapes with rules that are often congruent with the fiscal policies put in place. The public institutions funded by this spending come with both a formal legal framework and accompanying cultural expectations, for instance that food inspectors should be paid so that food borne illnesses be reduced or that children should be educated as a government obligation. Corruption of various types can and does interfere with the expression of moral values by public spending and institution building but in most regimes does not completely defeat the purpose of having a government itself. (The notion that there is or could be “corruption” implies that in fact there does exist a norm of government pursuing public ends from which corruption deviates.) The use of money then for these purposes transforms its value and scope of application. In the modern money system and currency-issuing government’s fiscal operations, there is a constant “re-orientation” of monetary value via the processes of spending and taxation, the former creating money and the latter destroying it. The moral dimension then of monetary exchange is continually maintained by government’s overall political-ethical-economic role.

In addressing climate change, the spending and taxing authority of government is critically important in orienting monetary exchange both between government and the private sector as well as within the private sector towards the public goals of preserving a habitable climate for this and future generations. The accretion of years of public policy and government spending in some nations combined with the rise of environmental movements has already contributed to markedly different outcomes in terms of per capita & per GDP carbon emissions. Many of the necessary physical goods needed to lower or eliminate the net carbon emissions of society will be provided by or financed directly by government; these include an altered streetscape enabling safer biking, walking and public transit, much better electric public transit as well as long-distance electricity transmission for renewable energy generators. Carbon taxation and other regulations of the private sector might then be implemented to drive private decision-making in areas where the choices of private-sector actors will make rapid, decisive differences in emissions and social outcomes. Governments with modern floating non-convertible currencies do not need to tax in specific amounts to finance or “balance” spending, so carbon or other taxation in specified amounts is not required to fund expenditures. The latter point is critical for understanding the room for decision and maneuver that such governmental leaderships have in addressing crises or everyday public needs.

5. Self Interest

Clearly economic and other forms of self-interest such as social status accumulation will play a role in climate action as it does now in our current society. People are motivated by acquisition of new objects as well as holding onto existing possessions; they are also motivated by considerations of social status. The use of money as a measure of value of objects as well as various debts and obligations is a technology for which we have do not have any likely substitutes. Money is flexible and its value can be transformed, as described above, to satisfy some combination of public and private purposes.

The shaping of markets to harness the drive to accumulate money and/or social status to the ends of the transition to a sustainable energy economy does not necessarily contradict the application of other motive forces to cut emissions. However, the sole focus on monetary self-interest as contained within the carbon pricing framework, leaves out of the picture some of the primary “motors” of timely, decisive climate action as listed here, most particularly ethical concern as well as the institution building and spending capacity of monetarily-sovereign governments.

The Implications of Multiple Motives

If one accepts the above model or an analogous one there are a number of practical consequences that stem from its application:

Realism

Rather than condense motivation to one, possibly internal, motivating factor as has been the tendency in much social science theory, a multiple motives theory gets our descriptions of the world closer to what seems to actually happen in real life. We experience multiple internal motivations that sometimes conflict, and then social institutions and social influence are added as factors that yield outcomes that cannot be reduced to the internal motivations of individuals.

Dynamics

One dimension of realism is dynamics. With multiple motivations come different forces pushing on people and society, yielding some kind of development over time. While a single force could be thought to wax and wane, this would then beg the question of why it waxed and waned.

Internal and External Conflict

Another dimension of realism is conflict. People are internally conflicted and also have conflicts of interest with each other. Both are features of the real world. There are real conflicts about social and economic resources and also conflicts of ideas and motivations.

One of the primary conflicts in this particular model, as in reality, is between ethical motivation and self-interested motivation. The latter can often be expressed in the context of capitalist societies between those with a socialistic motivation and those with a capitalistic motivation. Sometimes this conflict is played out between representatives of government or social movements on the one hand and representatives of businesses and political representatives of business interests on the other.

Actionability

The multiple motive model enables climate activists to understand and push for effective climate action. The model contains both the method of action of some future effective climate policy as well as the means by which that climate policy would be implemented.

Prioritization of Motives

Clearly, as in the conflict above, some motives should be allotted priority in the structure of climate policy and climate action. Ethical motivation must have in the broad design of climate policy priority over self-interested motivation, especially as the latter currently rules our society. On the other hand, self-interest should not be excluded from climate action, nor can self-interest be entirely reduced to ethical motivation.

2 responses to “What are the Motive Forces for Effective Climate Action?”