By J.D. Alt

I’d like to propose an Essay Contest that might inform us better than any news talk show or presidential debate what we’re up against with our National Budget—and what might be the best course of action we should consider. Everyone in Congress should be required to participate, governors and state legislators who might become future congressional leaders should be encouraged to join in, and op-ed economic analysts invited to submit. The essays would be posted on a Congressional website established specifically to enable the public to vote on the best explanation of the topic. The topic I propose is this:

I’d like to propose an Essay Contest that might inform us better than any news talk show or presidential debate what we’re up against with our National Budget—and what might be the best course of action we should consider. Everyone in Congress should be required to participate, governors and state legislators who might become future congressional leaders should be encouraged to join in, and op-ed economic analysts invited to submit. The essays would be posted on a Congressional website established specifically to enable the public to vote on the best explanation of the topic. The topic I propose is this:

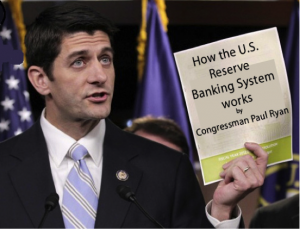

How the U.S. Reserve Banking System works—and why it matters to our National Budget.

I’m not suggesting that congresspersons and senators need to become economic experts, only that they explain, in their own words, their basic understanding of how the nation’s monetary system works. This doesn’t seem unreasonable: It can’t be asking too much from the people who are casting votes on Federal Budget issues on behalf of American citizens—or from the news media that informs us about their efforts. The essays don’t need to be overly long or go into great detail, just the basic gist of things, like you might explain it to your ten year old daughter if she asked one day, out of the blue, “Daddy, how does the U.S. Reserve Banking System work?”

To demonstrate and give this idea a test, here is my personal version of what I’d submit if I were a congressperson.

How the U.S. Reserve Banking System works (my understanding) By J.D. ALT, (pretend Congressman-elect from the state of Maryland.)

Most of us, including myself until about two years ago, believe the Reserve Banking system is a set of rules that establishes what percentage of a bank’s deposits the bank can lend out to other people. If a bank has $10 million in deposits from the American people, for example, the bank can only loan out, say, $8 million of those Dollars. The rest have to be kept in “reserve” in case some of the depositors want to withdraw their Dollars. That’s what “reserve” banking means, and its purpose is to make the banking system safe for depositors, while still enabling banks to make loans.

This seems to make a lot of sense. But just a little research and reading reveals that it’s nothing more than a myth.

The U.S. Reserve Banking system, in fact, begins with the Federal Reserve (America’s Central Bank) issuing sovereign fiat currency (U.S. Dollars) and the U.S. Treasury spending those Dollars—for goods or services, or to make transfer payments to individual citizens (e.g. social security payments). This is the only way it can begin. It cannot begin with people making deposits in banks, because until the Federal government issues and spends some Dollars, there aren’t any Dollars for the people to deposit. And it cannot begin with banks making loans to people because, by U.S. law, “bank dollars” (created when a bank makes a loan) must be convertible on demand to real U.S. Dollars (the ones issued by the U.S. government)—which is what happens when you convert the “bank dollars” in your bank account into real U.S. Dollars at an ATM machine. Before a bank can make a loan, creating “bank dollars”, real U.S. Dollars therefore must have been created first (in order for them to be available in the ATM machine)—and these real U.S. Dollars, as I’ve just said, can only have been created by the process of the Federal Reserve issuing them, and the Treasury spending them.

Because banks must, on a daily basis, be able to convert some portion of their “bank dollars” to real U.S. Dollars, they must keep a supply of real U.S. Dollars in a special account which is reserved specifically for that purpose. This is the bank’s “reserve” account. Each bank has a “reserve” account, and that account is located at the Central Bank (the Federal Reserve). Every business day, banks withdraw enough real U.S. Dollars from their reserve account to cover the ATM, check-cashing, and direct withdrawal transactions they anticipate for that day. Sometimes they miscalculate and an armored truck has to deliver the bank additional U.S. Dollars from their reserve account.

Banks use their reserve account in another way as well: When a customer writes a check on their account at bank A—say to buy groceries—and the grocery store then deposits that check in its account at a bank B, at the end of the business day the different banks have to “reconcile” this transaction. That means dollars have to be moved from the account at bank A to the account at bank B (to pay for the groceries.) But this transaction is not made with “bank dollars”, because bank B doesn’t want bank A’s “bank dollars”—it wants to be paid in real U.S. Dollars. So, at the end of the business day, the reconciliation is made between the two bank’s reserve accounts at the Central Bank: Some of bank A’s reserve Dollars are withdrawn and deposited into bank B’s reserve account to cover the amount of the check written for groceries.

How does a bank get the real U.S. Dollars in its reserve account so it will have enough of them to cover these needs? They can borrow the U.S. Dollars from another bank, or from the Central Bank (something they actually do, as a matter of course, every business day.) But the main way they get the real U.S. Dollars is through Federal spending. When the Federal government pays someone a Social Security payment, for example—let’s say $1,000—the bank is instructed to deposit that amount of “bank dollars” in the person’s bank account. But another deposit is simultaneously made: the Federal government issues and deposits $1,000 of real U.S. Dollars in the bank’s reserve account. Two deposits, then, are made simultaneously—the S.S. recipient’s bank account gets 1,000 “bank dollars”, and that bank’s reserve account gets 1,000 real U.S. Dollars. But don’t imagine the citizen is getting cheated here—remember, he or she can always convert the “bank dollars” to the real U.S. Dollars any time they want (which is why the reserves are there in the first place.)

But why do we do things in such a complicated way? Why do we have these two kinds of “money”—real U.S. Dollars and “bank dollars”? The answer is because it is a direct reflection of reality: When a bank makes a loan, it is NOT temporarily giving to citizen B some of the money citizen A has deposited in the bank. Instead, it is temporarily creating new money which it uses to make the loan. But banks, by law, cannot create new U.S. Dollars (only the Federal government can do that)—so the bank creates “bank dollars” instead. From the perspective of the person getting the loan, there is no difference between getting “bank dollars” and getting real U.S. Dollars because, as we’ve already emphasized, by law the “bank dollars” are convertible to real U.S. Dollars on demand. The system works because only a small percentage of the “bank dollars” issued by banks are actually converted to real Dollars on any given day—and most of the “bank dollars” eventually get “cancelled” when the loans are repaid.

The Reserve Banking system, then, is a method that enables banks to leverage the relatively “small” number of real U.S. Dollars (which are issued and spent into the economy by the Federal government) into a great quantity of “bank dollars” which function very well as “money” in the vast majority of cases. In fact there’s only one thing you can’t pay for with “bank dollars”: you can NOT pay your Federal taxes with them. When you write a check on your bank account to pay your Federal taxes, the bank must make that payment good by delivering real U.S. Dollars from its reserve account because that is the only kind of “money” the Federal government will accept.

This last point is critically important for every Congressman (like myself) to understand when voting for items in the Federal Budget. The reason it’s important is because it shines a spot-light on one very simple calculation: When the Federal government spends it ADDS real U.S. Dollars to the reserve banking system. When the Federal government collects taxes, it SUBTRACTS real U.S. Dollars from the reserve system. This means that if, in a given budget year, the Federal government subtracts more Dollars from the system (tax collections) than it adds to the system (Federal spending), there will be net FEWER real U.S. Dollars in the system for the banks to leverage upon. Fewer real U.S. Dollars for the banks to leverage upon means the banks will have to reduce the amount of “bank money” they are creating with loans, and the economy will be forced to contract—increasing unemployment and social misery.

What is clear, then, is that there should be something called a “General Rule for National Budget Planning”, and it should be this: The Federal government always needs to spend MORE Dollars than it collects in taxes. That is the only way the Private Sector economy (operating on the leveraging and spending of “bank dollars”) can grow within the parameters and boundaries of the U.S. Reserve Banking system.

This is why it’s so ridiculous for us congress-people to be harping all the time about Federal “deficits”, as if it were an unconscionable crime for the Federal government to spend more Dollars than it collects in taxes—and why it is so ridiculous for the op-ed economic experts to claim the Federal government has to borrow Dollars to make up for its deficit spending. Federal government bonds are not “borrowed” money—they are simply savings accounts the Central Bank sets up for citizens to keep their own extra Dollars in when they can’t think of anything better to do with them. And, now that I think about it, the interest the Federal government pays on those bond “savings accounts” is another primary way that real U.S. Dollars get issued and spent into the Reserve Banking System.

I may not have everything just right, and I’d be happy for people to comment and suggest corrections where I’m wrong. That, ultimately, is the purpose of the essay contest: not for someone to actually win the contest, but for all of us, together somehow, to understand the way things really work.

39 responses to “Essay Contest for Congress”