By Ben Strubel

Before I begin this article want to make the point that what I’m about to say doesn’t apply to everyone in the industry. While the average mutual fund, broker, wealth manager, and hedge fund charges high fees and delivers poor results it doesn’t apply to everyone. I know lots of good, honest hedge fund managers that charge reasonable fees. I know lots of wealth managers that act in their client’s best interest and don’t gouge them on fees. Unfortunately these are the exceptions rather than the rule.

Over the past year or so, the issue of rising income inequality in the United States (and even worldwide) has come front and center. Most of what I’ve read has focused on wages, union membership, unemployment, taxation, government subsidy, and executive pay issues.

There is one issue whose role I think is overlooked in the mainstream media: the role the financial sector plays in exacerbating income inequality. In fact, I believe the financial sector is one of the prime causes, and at its current point is perhaps the greatest parasite in human history. It is sucking wealth from the productive sectors of the economy at an unprecedented rate.

Before we go any further, I want to define the term “income inequality.” When I use that term, I am referring to the fact that, on average, the incomes and standard of living of American workers is not keeping pace with productivity. I’m also using the term, in part, to explain why workers and executives in some parts of the economy are overpaid in relation to the benefits they provide. What I am not doing is making a blanket statement that money should be taken away from successful, hardworking people and given or “redistributed” to the lazy.

The Role of the Financial Sector

In economics, the financial sector is typically lumped in with the insurance sector and real estate (the financial portion of the real estate sector, not construction) sector. Together, the sectors are often abbreviated and called the FIRE sector. In this article I will talk mainly about the finance portion of the FIRE sector since it is by far the largest, most visible, and most corrupt.

The problem is that the financial, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) sectors do not actually produce any goods or services. If you go on Google Finance you’ll see it divides the economy into ten sectors: energy, basic materials, industrials, cyclical consumer goods, non-cyclical consumer goods, financials, healthcare, technology, telecommunications, and utilities.

The nine nonfinancial sectors all produce goods or services. For example, the energy sector companies drill for our oil and refine it into gasoline (e.g., ExxonMobil); the basic materials sector mines our iron (BHP Billiton) and refines it into steel (Nucor); the industrial sector produces the mining equipment (Caterpillar) used by the previously mentioned sectors; the cyclical consumer goods sector produces our cars (Ford) or sells our everyday items (Wal-Mart); the non-cyclical consumer goods sector sells the things we need no matter what, such as groceries (Safeway); the healthcare sector provides the medicines that heal us (Johnson & Johnson); the technology sector gives us the computers and software we use (Apple); the telecommunications sector gives us the ability to communicate (Verizon); and the utility sector gives us the power to run our homes and businesses (Duke Energy).

The financial sector? Well, according to Harvard professor Greg Mankiw, chief academic apologist for the financial sector, this is what it’s supposed to do:

Those who work in banking, venture capital, and other financial firms are in charge of allocating the economy’s investment resources. They decide, in a decentralized and competitive way, which companies and industries will shrink and which will grow.

The job of the finance sector is simply to manage existing resources. It creates nothing. Therefore, the smaller the financial sector is the more real wealth there is for the rest of society to enjoy. The bigger the financial sector becomes the more money it siphons off from the productive sectors.

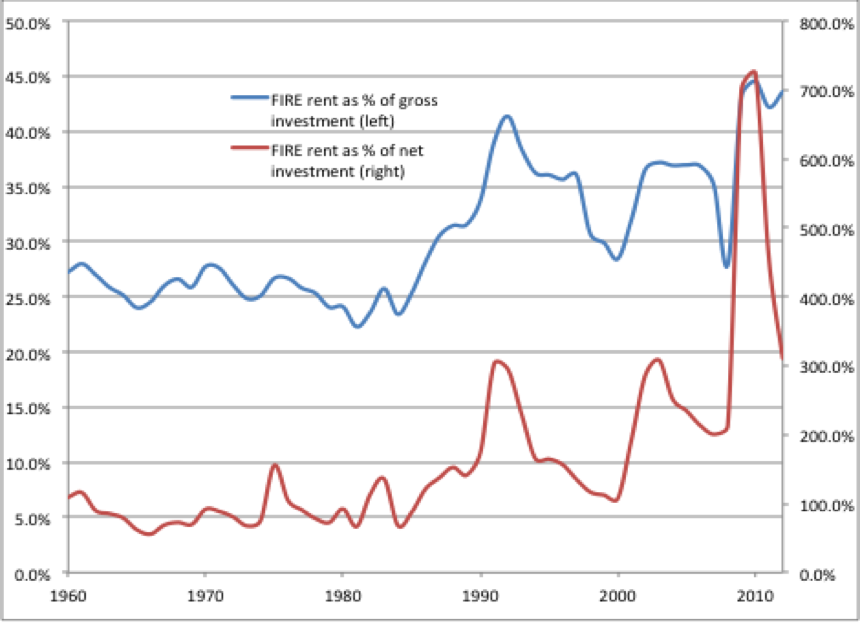

The graph below shows how the financial sector has grown since 1960. The figures are shown as a percentage of investment (using both gross and net investment).

Graphic source: Jacobin Magazine

As you can see, the financial sector has almost doubled or tripled in size since 1960. That means it is extracting double or triple the amount of money from the real economy!

Just how much?

I want to go through several areas of the economy to show you how the financial sector is extracting money and offering no benefit.

The Grift in Your Retirement Plan

I want to start with the industry I work in, wealth management. When I started my business, I was cognizant of how investors were ill served by the traditional model of wealth management and vowed to run my business differently. Unfortunately, a vast majority of the financial industry has built an unrivaled apparatus for extracting huge sums of money from retirees and mom-and-pop investors.

Say, you’re sitting on your couch, watching TV and thinking about retirement. You just got part of your inheritance and think investing it for the future would be a sensible idea. Imagine you haven’t the slightest idea how to get started. Then a commercial comes on with Tommy Lee Jones telling you how trustworthy Ameriprise is. Maybe you hear the reassuring voice of John Houseman pitching Smith Barney, or you might see the iconic bull charging across the desert for Merrill Lynch.

Say you decide to go down to your local brokerage and meet with a financial advisor. His (or her) pitch sounds good, so you decide to become a client.

The first problem is the guy you met. Remember how he told you he has his finger on the pulse of the market, he has access to the best investment research, he is always taking continuing education classes, and he is always monitoring your portfolio? He isn’t. He could be a complete moron. He got hired (and survived and thrived) because he is a good salesman. Nothing less and nothing more. He takes his orders on what to sell from the top — the gaggle of people with their fingers in your retirement pie, helping themselves to regular bites.

The first person behind the scenes telling our hapless salesman what to do is some sort of office, district, or regional manager. This is manager is just like the salesman but with more ambition. Almost all of these guys were promoted from sales, and their job is do an impersonation of Alec Baldwin from Glengarry Glen Ross, yelling at the underperformers (“Coffee is for closers!”) to get out there and sell the turd of the month. (“XYZ Mutual Fund Company just paid our firm $200M,” this manager says, “so get out there and sell their funds! And, Jones, if you don’t gross $20,000 by the end of this month you’re fired! Meeting adjourned.”)

Neither of these two friendly fellows actually does much, if anything, in the way of actual investing. Sure, they learn the lingo, dress sharply, and probably know more than the average Joe, but they don’t call the shots. That happens at Big Bank HQ.

Somewhere in the belly of the beast there is a gaggle of highly paid, largely worthless economists and market technicians. Using some combination of tea leaves, voodoo, crystal balls, and tarot cards, these guys come up with the selection of one-size-fits-most, happy-meal portfolios that clients will be invested in. Actually, scratch that. Portfolios aren’t assembled using all kinds of mystical methods; they are assembled using cold hard cash. (It’s the finance sector. Did you think they spoke a language other than green?) See, various mutual fund companies pay marketing fees and other dubiously legal payments to the advisory firms to get them to sell their funds. In 2010, mutual fund companies paid $3.5B in perfectly legal “pay to play” schemes to get their funds featured in various investment lineups.

You, the investor, are usually charged somewhere around 1% to 1.5% of assets annually for this “service.” I’ve seen clients charged as much as 1.65% and I’ve come across firms advertising fees as high as 2% per year for clients with small account balances. For large portfolios (typically $1M or more) the fees start going down and I’ve seen rates as low as .5% or less. These fees are split up between your advisor, the district manager, and the firm itself. Keep in mind that these are fees before any investments have been made!

So who actually makes the investments in stocks and bonds? It’s the portfolio managers at the mutual fund companies. According to the Investment Company Institute 2011 Fact Book (the ICI is a pro-mutual fund organization), the average mutual fund in 2010 charged 1.47% of assets annually. That’s in addition to an average up-front sales charge of 1%.

Why so expensive? Well, the funds are towing a lot of dead weight. According to the ICI 2013 Fact Book, only 42% of mutual fund employees were employed in fund management positions or fund administrative positions. The rest, 58%, were employed in either investor servicing (34%) or sales and distribution (24%) job functions.

Like any good infomercial says, “But wait! There’s more!” When you buy a stock or bond, you can’t just go grab it off the shelf like you are shopping at Wal-Mart. You need to go through a brokerage. A 1999 study by Chalmers, Edelen, and Kadlec found that the average mutual fund incurs trading expenses of .78% per annum. A newer study in 2004 by Karceski, Livingston, and O’Neal found brokerage commissions cost funds around .38% per annum, or .58% if you account for the effect trading large blocks of stock has on the bid-ask spread.

But wait! There’s more! Mutual funds and your average retail investor are relatively unsophisticated, so a new industry has popped up to take advantage of them. It’s called “high frequency trading” or HFT for short. These are powerful computers programmed to take advantage of “dumb” traders in the market. These HFT firms place their computers physically next to the stock exchange computers in the datacenters and buy access to market quotes milliseconds before they are made public. They use these and other advantages to skim profits from other legitimate investors (that is, people buying stocks because they want to own part of the underlying company).

All told, it’s not uncommon to see investors incurring annual expenses of 2%, all the way up to 4% per year.

Institutions and the Rich Have the Same Problem

The problem isn’t just limited to Joe Six-pack Retiree. Large institutional investors, such as pension funds, and “sophisticated” rich investors get taken to the cleaners too.

Once upon a time someone came up with a great idea: Since an all-stock portfolio is volatile, why not “hedge” the portfolio and sell some stocks short? If you bet that good stocks will go up (buying stocks in the good companies or going long) and bad stocks will go down (selling the stock short) then you could limit volatility and maybe make some extra money. (You’d make money both when the good stocks went up and the bad stocks went down). It was and is a pretty good idea when done correctly. Unfortunately, the term “hedge fund,” like the term “mutual fund,” has lost its original meaning. The term hedge fund is now used to refer to any type of pooled investment vehicle that is limited to select clients (usually rich, sophisticated investors and institutions, although the rules vary worldwide).

The rule of thumb is that hedge funds charge a 2% per year management fee and keep 20% of all profits, the proverbial “2 and 20” compensation. According to a WSJ article, this old adage isn’t too far off; the average hedge fund charges 1.6% per year and keeps 18% of profits.

In 2012, hedge funds removed $50.5B from their investors’ pockets. In fact, according to an article in Jacobin Magazine, the top 25 hedge fund managers make more money than the CEOs of all S&P 500 companies combined. Combined!

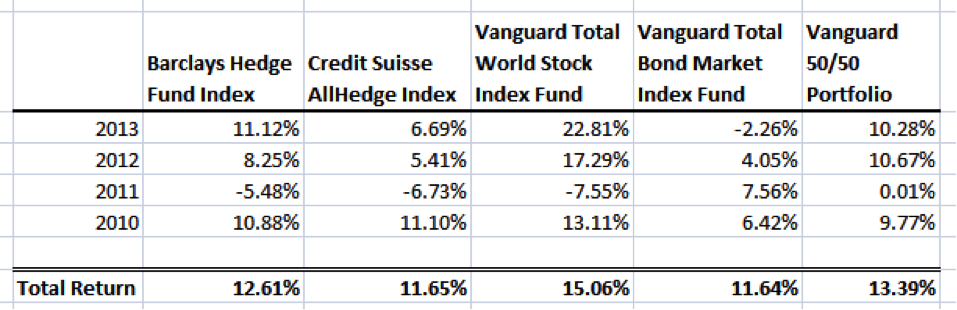

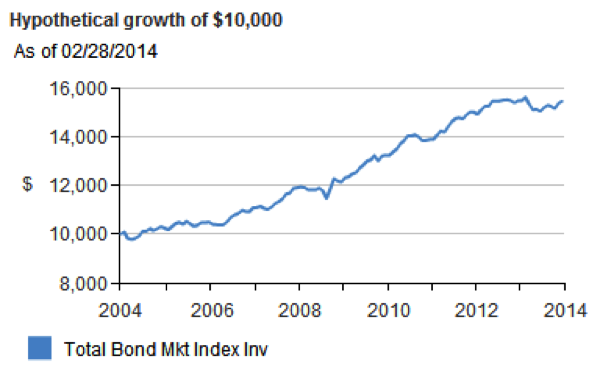

Have they earned it? Well, the answer seems to be no. I pulled the last four years of return data for two hedge fund indices: the Barclays Hedge Fund Index and the Credit Suisse AllHedge Index. These two indices track thousands of hedge funds across the globe. I compared them with the returns of the Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund and the Vanguard Total World Bond Market Index Fund as well as a 50/50 portfolio of the two Vanguard Funds. All returns shown are net of fees.

The Vanguard stock fund trounced both hedge fund indices, and the Credit Suisse index managed only to beat the returns of bonds by .01%.

Right about now you will hear the howls of the “hedgies” complaining. I wasn’t quite fair to the hedge funds. A lot, but not all, of them are hedged so returns in down markets will be better and four years isn’t a terribly long time to look at.

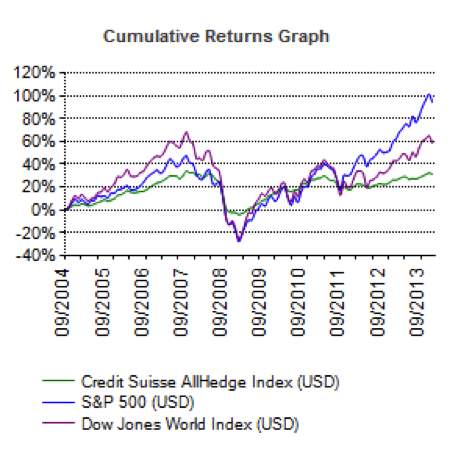

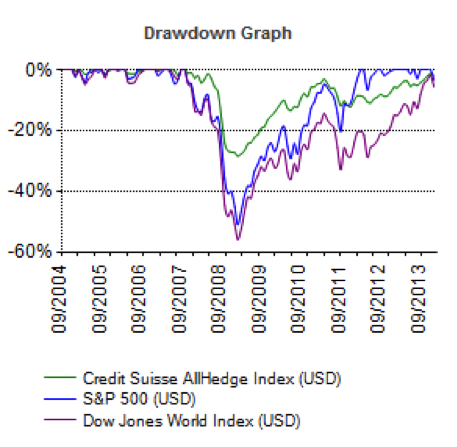

The two graphs below show the returns for the Credit Suisse index since 2004 and the maximum drawdowns (losses) since 2004.

First, over 10 years the returns for hedge funds are atrocious, only about 25% in total. They do have a point that the draw downs are lower. The maximum losses experienced during the downturn only averaged about 25%. Fine, but the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index had barely any draw downs during the crisis and returned over 50% during a similar time period.

Unfortunately, Vanguard does not have return data for any of its World Stock funds for a complete 2008 calendar year so I was unable to get exact data for my 50/50 portfolio. But I’d be willing to bet it beats the hedge fund indices on a risk adjusted basis.

When you hear about underfunded pension plans, part of the blame lies with pension investment committees and their investments in hedge funds. These funds, in aggregate, have not earned the fees they charge and have instead funneled the money of retirees into the hands of a wealthy few.

I’m not alone in reaching this conclusion. Pension funds are slowly starting to see the light and reducing their allocations to “alternative” investments, such as hedge funds, and reallocating the capital to indexed products or negotiating with the funds for lower fees.

It’s not just the traditional investment arena where the financial sector has run wild. Its unending quest for siphoning money from the economy has spilled out into other areas.

Speculation in Commodities Costs Main Street Billions

Speculation by the financial sector in the commodities market is impacting the entire world. The passage of the Commodities Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) has allowed big banks to engage in almost limitless speculation in the commodities market. Wall Street has convinced everyone from individual investors to pension funds and endowments that they need to include commodities in their portfolios for deworsification, I mean, diversification purposes. Between investors plowing more than $350B into the commodities market and what appears to be outright manipulation of commodities prices, the financial sector has increased the costs of everything from wheat to heating oil and aluminum to gasoline.

An executive for MillerCoors testified that manipulation of the aluminum market cost manufacturers over $3B. The World Bank estimated that in 2010, 44 million people worldwide were pushed into poverty because of high food prices. The chief cause? More than 100 studies agree the cause is speculation in the commodities market. (Goldman Sachs made $440M in 2012 from food market speculation.) For Americans who love their cars (and SUVs), the biggest impact might be felt at the gas pump where experts estimate that financial speculation has added anywhere from $1 to $1.50 to gas prices.

For more information on speculation in the commodities, I recommend Matt Taibbi’s excellent pieces, in-depth information at Better Markets, or some of my articles on commodities.

If you think it’s bad enough that Wall Street is raising the price of your food, heating oil, gasoline, and Pepsi, then wait until you get a load of one of the Street’s other ingenious ideas for helping themselves to more of your money.

Corruption of Public Infrastructure

One significant source of profit for the financial sector has been exploiting public, taxpayer-owned infrastructure. It should be blatantly obvious that these deals are bad for citizens, as the fees charged to citizens for use of the asset must not only cover servicing costs and maintenance capital expenditures but must also generate profit for the firms buying the assets.

The first and most obvious examples of this type of fraud (I choose to use the term “fraud” because I believe that is exactly what these deals are) are government entities selling public, taxpayer-owned infrastructure, such as road, bridges, parking facilities, and ports, to the private sector so that they can extract rent from the users. The deals are usually touted as saving taxpayers money and letting the “more efficient” private sector better manage the asset. This is false. Many studies show private ownership of public goods does not lead to any cost savings. A comprehensive econometric study done in 2010 of all available public vs. private studies by Germa Bel, Xavier Fageda, Mildred E. Warner at the University of Barcelona found no cost saving in privatizing public water or solid waste management services and infrastructure.

The case is no different when it comes to public roads. A 2007 paper by US PIRG found that privatizing roads never benefits citizens. Financial firms were typically able to buy the assets on the cheap and then raise toll rates while usually sneaking language into the agreements that prevented governments from building competing infrastructure. The paper presented evidence that the Indiana Toll Road lease will cost taxpayers at least $7.5B.

One of the most egregious examples of the financial sector extracting rent is the 2009 sale of Chicago’s parking meters to a consortium led by Morgan Stanley. Shortly after the lease was finalized, rates at many parking meters increased (in some case by quadruple the amount). The Chicago Inspector General found that the city was underpaid by almost $1B for the lease. Meanwhile, in 2010 Morgan Stanley banked $58 million in profits from the parking meters. With no way out of the deal, the citizens of Chicago are now paying Morgan Stanley for the right to use assets they used to own!

The second way in which taxpayers are exploited by the financial sector is so-called public-private partnerships (also referred to as PPP or P3). There is no set definition for what constitutes a PPP arrangement, and it is possible some might be beneficial in limited circumstances. I want to focus on one specific type of PPP that enriches the financial sector: when public projects are privately financed. There is absolutely no reason for any government project to ever require paying “rent” to the financial sector in the form of financing. The United States federal government is the monopoly supplier of US dollars. It can add them to the economy at will through deficit spending or remove them via taxation. There is no earthly reason for a public entity to be forced to depend on the private sector to provide any type of financing. The only constraint on whether or not money should be spent is whether the economy is at full capacity (full employment and full industrial capacity utilization) where the additional deficit spending may cause inflation.

State and local governments are unable to issue currency and therefore must depend on revenue raised via taxation, distributions from the federal government, or money raised through bond issuance. Even then, studies have shown that PPPs are more expensive compared to the state or local entity securing financing through the municipal bond market.

As the financial sector funnels more and more resources into lobbying and bribes (let’s face it, campaign contributions are nothing more than legal bribery), it has been able to strip an ever-greater amount of state-owned assets from the public. Public asset strip mining is one of the chief causes of the increasing profitability of the financial sector.

So far we’ve dealt with examples that are pretty easy to see. Everyone who owns a car knows that gas prices have been rising too fast and food is more expensive. The citizens of Chicago know they are getting shafted on the parking meter deal since parking rates have quadrupled. But there are hidden areas of the economy where the financial sector is ripping off the public too.

Interest Rate Manipulation

Do you know what LIBOR is? And what it’s used for? A lot of financial types read my newsletters, so I’m sure some of you do. But the average man or woman on the street likely does not.

LIBOR stands for London Interbank Offered Rate and is the average interest rate banks in London estimate that they would be charged if they borrowed from other banks. This rate is used worldwide by mortgage lenders, credit card agencies, banks, and other financial institutions to set interest rates. By some estimates, more than $350T in financial products, derivatives, and contracts are tied to LIBOR.

In 2012, it was discovered that, since 1991, banks were falsely inflating or deflating the interest rates they reported. (Remember banks essentially make up their own interest rates and report them with the results being essentially averaged and reported as LIBOR.) The banks did this in order to profit from trades or to make themselves look more creditworthy than they were.

The Macquarie Group estimated that the manipulation of LIBOR cost investors $176B. (Keep in mind this is an estimate coming from a financial firm, so it would be prudent to assume it’s on the low end.)

Andrew Lo, a finance professor at MIT, said the fraud “dwarfs by orders of magnitude any financial scam in the history of the markets.”

Food Stamps (SNAP) and Welfare (TANF)

I highly doubt any of my clients or readers are beneficiaries of the SNAP or “food stamps” program and are probably not very familiar with it. While it is nominally a government program it has been corrupted by the big banks. Benefits are provided electronically via debit cards (EBT cards). JP Morgan has made over $500M from 2004 to 2012 providing EBT benefits to 18 states. The banks then are free to reap fees from users for such things as cash withdraws for TANF benefits, out of network ATM fees, lost card replacement fees, and even customer service calls.

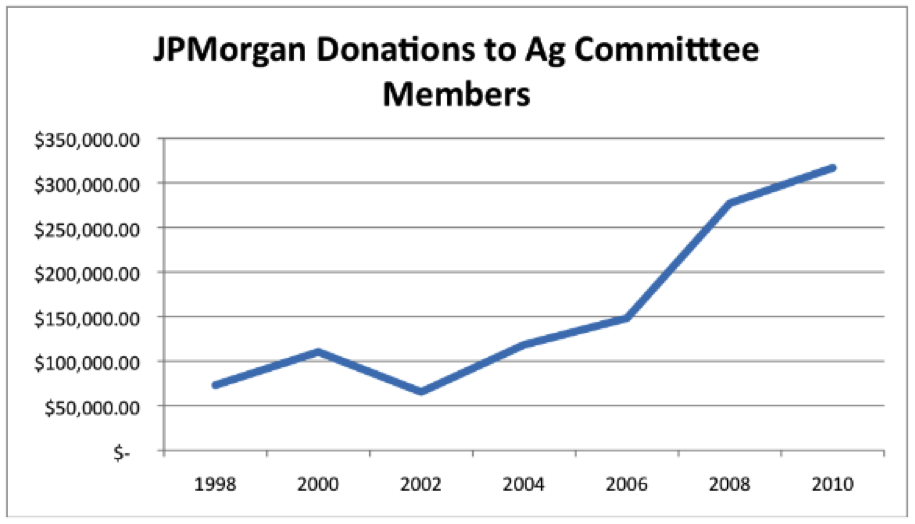

I believe you can judge how profitable a service is to a company how much it spends on lobbying. In the case of JPMorgan, its bribes, I mean campaign contributions to Agriculture Committee (SNAP is part of the Department of Agriculture) members increased sharply after it entered the EBT market in 2004.

(Graphic source: GAI via data from CRP)

Summary

A bloated and out-of-control financial sector does not add any value to society. Society benefits when the financial sector is kept as small as possible.

The financial sector is a parasite that depends on its host organism, the productive sector of the economy, to fuel its profits. The larger the financial sector grows, the more wealth it extracts from the productive sectors of the economy. With all due respect to Matt Taibbi, Goldman Sachs isn’t a vampire squid; the entire financial sector is the vampire squid with its tentacles reaching into the pockets of citizens everywhere and sucking out money.

32 responses to “The Financial Sector Is the Greatest Parasite in Human History”