Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

January 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Tag Archives: MMP

MMP #34 Functional Finance and Exchange Rate Regimes: The Twin Deficits Debate

In theprevious weeks, we examined the functional finance approach of Abba Lerner. Itis clear that Lerner was analysing the case of a country with a sovereigncurrency (or what many call “fiat” currency). Only the sovereign government canchoose to spend more whenever unemployment exists; and only the sovereigngovernment can increase bank reserves and lower (short term) interest rates tothe target level. It is important to note that Lerner was writing as theBretton Woods system was being created—a system of fixed exchange rates basedon the dollar. Thus it would appear that he meant for his functional financeapproach to apply to the case of a sovereign currency regardless of exchangerate regime chosen.

Still itmust be remembered that all countries in Lerner’s time adopted strict capitalcontrols. In terms of the “trilemma” they had a fixed exchange rate anddomestic policy independence, but did not allow free capital flows. We haveseen that domestic policy space is greatest in the case of a floating currency,but that adopting capital controls in combination with a managed or fixedexchange rate can still preserve substantial domestic policy space. That isprobably what Lerner had in mind. Most countries with fixed exchange rates andfree capital mobility would not be able to pursue Lerner’s two principles offunctional finance because their foreign currency reserves would be threatened(only a handful of nations have amassed so many reserves that their position isunassailable). Managed or fixed exchange rates, with some degree of constrainton capital flows, can provide the required domestic policy space to pursue afull employment goal.

Weconclude: the two principles of functional finance apply most directly to asovereign nation operating with a floating currency. If the currency is pegged,then the policy space is more constrained and the nation might have to adoptcapital controls to protect its international reserves in order to maintainconfidence in its peg.

The US Twin Deficits Debate. Deficit hawks in the US frequentlyraise three objections to persistent national government budget deficits: a)they pose a solvency risk that could force to government default on its debt;b) they pose an inflation, or even a hyperinflation, risk; and c) they impose aburden on our grandkids, who will have to pay interest in perpetuity to the Chinesewho are accumulating US Treasuries as well as power over the fate of theDollar. This often leads to the claim that the US Dollar is in danger of losingits status as international reserve currency.

We haveseen that national budget deficits and debts do not matter so far as nationalsolvency goes. The sovereign issuer of the currency cannot be forced into aninvoluntary default. We also have dealt with possible inflation effects of deficitspending (more on that later). To summarize that argument as briefly aspossible, additional deficit spending beyond the point of full employment willalmost certainly be inflationary, and inflation barriers can be reached evenbefore full employment. However, the risk of hyperinflation for a sovereigncountry like the US is low.

Later wewill address the connection among budget deficits, trade deficits and foreignaccumulation of treasuries, the interest burden supposedly imposed on ourgrandkids, and the possibility that foreign holders might decide to abandon theDollar.

Let us setout the framework thoroughly examined in previous blogs. At the aggregatelevel, the government’s deficit equals the nongovernment sector’s surplus. Wecan break the nongovernment sector into a domestic component and a foreigncomponent. As the US macrosectoral balance identity shows, the governmentsector deficit equals the sum of the domestic private sector surplus plus thecurrent account deficit (which is the foreign sector’s surplus). We will put tothe side discussion about the behaviors that got the US to the currentreality—which is a large federal budget deficit that is equal to a (large)private sector surplus (spending less than income) plus a rather large currentaccount deficit (mostly resulting from a US trade balance in which importsexceed exports).

There is apositive relation between budget deficits and the current account deficit thatgoes behind the identity. All else equal, a government budget deficit raisesaggregate demand so that US imports exceed US exports (American consumers areable to buy more imports because the US fiscal stance generates householdincome used to buy foreign output that exceeds foreign purchases of US output.)There are other possible avenues that can generate a relation between agovernment deficit and a current account deficit (some point to effects oninterest rates and exchange rates), but they are at best of secondaryimportance if not wrong.

To sum up:a US government deficit can prop up demand for output, some of which isproduced outside the US—so that US imports rise more than exports, especiallywhen a budget deficit stimulates the American economy to grow faster than theeconomies of our trading partners.

Whenforeign nations run trade surpluses (and the US runs a trade deficit), they areable to accumulate Dollar denominated assets. A foreign firm that receivesDollars usually exchanges them for domestic currency at its central bank. Forthis reason, a large proportion of the Dollar claims on the US end up atforeign central banks. Since international payments are made through banks,rather than by actually delivering US federal reserve paper notes, the Dollarsaccumulated in foreign central banks are in the form of reserves held at theFed—nothing but electronic entries on the Fed’s balance sheet. These reservesheld by foreigners (mostly, central banks) do not earn interest.

Since the central banks would prefer to earninterest, they convert them to US Treasuries—which are really just anotherelectronic entry on the Fed’s balance sheet, albeit one that periodically getscredited with interest. This conversion from reserves to Treasuries is akin toshifting funds from your checking account to a certificate of deposit (CD) atyour bank, with the interest paid through a simple keystroke that increases thesize of your deposit. Likewise, Treasuries are CDs that get credited interestthrough Fed keystrokes.

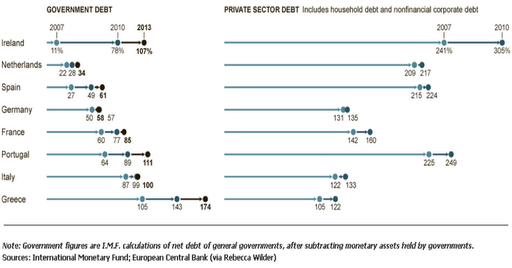

In sum, aUS current account deficit will be reflected in foreign accumulation of USTreasuries, held mostly by foreign central banks. You can see the evidencehere, in Figures 2 and 3:

While thisis usually presented as foreign “lending” to “finance” the US budget deficit,one could just as well see the US current account deficit as the source offoreign current account surpluses that can be accumulated as treasuries. In asense, it is the proclivity of the US to simultaneously run trade andgovernment budget deficits that provides the wherewithal to “finance” foreignaccumulation of US Treasuries. Obviously there must be a willingness on allsides for this to occur—we could say that it takes (at least) two to tango—andmost public discussion ignores the fact that the Chinese desire to run a tradesurplus with the US is linked to its desire to accumulate Dollar assets. At thesame time, the US budget deficit helps to generate domestic income that allowsour private sector to consume—some of which fuels imports, providing the incomeforeigners use to accumulate Dollar saving, even as it generates Treasuriesaccumulated by foreigners.

In otherwords, the decisions cannot be independent. It makes no sense to talk ofChinese “lending” to the US without also taking account of Chinese desires tonet export. Indeed all of the following are linked (possibly in complex ways):the willingness of Chinese to produce for export, the willingness of China toaccumulate US Dollar-denominated assets, the shortfall of Chinese domesticdemand that allows China to run a trade surplus, the willingness of Americansto buy foreign products, the (relatively) high level of US aggregate demandthat results in a trade deficit, and the factors that result in a US governmentbudget deficit. And of course it is even more complicated than this because wemust bring in other nations as well as global demand taken as a whole.

While it isoften claimed that the Chinese might suddenly decide they do not want UStreasuries any longer, at least one but more likely many of these otherrelationships would also need to change. For example it is feared that Chinamight decide it would rather accumulate Euros. However, there is no equivalentto the US Treasury in Euroland. China could accumulate the Euro-denominateddebt of individual governments—say, Greece!—but these have different riskratings and the sheer volume issued by any individual nation is likely toosmall to satisfy China’s desire to accumulate foreign currency reserves.Further, Euroland taken as a whole (and this is especially true of itsstrongest member, Germany) attempts to constrain domestic demand to avoid tradedeficits—meaning it is hard for the rest of the world to accumulate Euro claimsbecause Euroland does not generally run trade deficits. If the US is a primarymarket for China’s excess output but Euro assets are preferred over Dollarassets, then exchange rate adjustment between the (relatively plentiful) Dollarand (relatively scarce) Euro could destroy China’s market for its exports.

This shouldnot be interpreted as an argument that the current situation will go onforever, although it could persist much longer than most commentators presume.But changes are complex and there are strong incentives against the sort ofsimple, abrupt, and dramatic shifts often posited as likely scenarios. Thecomplexity as well as the linkages among balance sheets ensure that transitionswill be moderate and slow—there will be no sudden dumping of US Treasuries—thatwould destroy the value of the financial wealth held by the Chinese, as well asthe export market they currently rely upon.

Beforeconcluding, let us do a thought experiment to drive home a key point. Thegreatest fear that many have over foreign ownership of US Treasuries is theburden on America’s grandkids—who, it is believed, will have to pay interest toforeigners. Unlike domestically-held Treasuries, this is said to be a transferfrom some American taxpayer to a foreign bondholder (when bonds are held byAmericans, the transfer is from an American taxpayer to an American bondholder,believed to be less problematic). So, it is argued, government debt really doesburden future generations because a portion is held by foreigners. Now, inreality, interest is paid by keystrokes—but our grandkids might decide to raisetaxes on themselves to match interest paid to Chinese bondholders and therebyimpose the burden feared by deficit hawks. So let us continue with ourhypothetical case.

What if theUS managed to eliminate its trade deficit so that it ran a perpetually balancedcurrent account? In that case, the US budget deficit would exactly equal the USprivate sector surplus. Since foreigners would not be accumulating Dollars intheir trade with the US, they could not accumulate US Treasuries (yes, theycould trade foreign currencies for the Dollar but this would cause the Dollarto appreciate in a manner that would make balanced trade difficult tomaintain). In that case, no matter how large the budget deficit, the US wouldnot “need” to “borrow” from the Chinese to finance it.

This makesit clear that foreign “finance” of our budget deficit is contingent on ourcurrent account balance—foreigners need to export to us so that they can “lend”to our government. And if our current account is in balance then no matter howbig our government budget deficit, we will not “need” foreign savings to“finance” it—because our domestic private sector surplus will be exactly equalto our government deficit. Indeed, one could quite reasonably say that it isthe budget deficit that “finances” domestic private sector saving.

Yet, thedeficit hawks believe the federal budget deficit would be more “sustainable” ifforeigners did not accumulate Treasuries that supposedly burden futuregenerations of Americans. But how could the US eliminate the current accountdeficit that allows foreigners to accumulate Treasuries? The IMF-approvedmethod of balancing trade is to impose austerity. If the US were to grow muchslower than all our trading partners, US imports would fall and exports wouldrise. In fact, the “great recession” that began in the US in 2007 did reducethe trade deficit—although only moderately and probably temporarily. In orderto eliminate the trade deficit and to ensure that the US runs balanced trade,it might need a much deeper, and permanent, recession. By reducing American livingstandards relative to those enjoyed by the rest of the world, the nation mightbe able to eliminate its current account deficit and thereby ensure thatforeigners do not accumulate Treasuries said to burden future generations ofAmericans.

Now, canthe deficit hawks please explain why Americans should desire permanently lowerliving standards on their promise that this will somehow reduce the burden onthe nation’s grandkids? It seems rather obvious that grandkids would prefer ahigher growth path both now and in the future, so that America can leave themwith a stronger economy and higher living standards. If that means that thirtyyears from now the Fed will need to stroke a few keys to add interest toChinese deposits, so be it. And if the Chinese some day decide to use dollarsto buy imports, America’s grandkids will be better situated to produce thestuff the Chinese want to buy.

Inconclusion, while there are links between the “twin deficits”, they are not thelinks usually imagined. US trade and budget deficits are linked, but they donot put the US in an unsustainable position vis a vis the Chinese. If theChinese and other net exporters (such as Japan) decide they prefer fewer dollarassets, this will be linked to a desire to sell fewer products to America. Thisis a particularly likely scenario for the Chinese, who are rapidly developingtheir economy and creating a nation of consumers. But the transition will notbe abrupt. The US current account deficit with China will shrink, just as itssales of US government bonds to Chinese (to offer an interest-paying substituteto reserves at the Fed) decline. This will not result in a crisis. The USgovernment does not, indeed cannot, borrow Dollars from the Chinese to financedeficit spending. Rather, US current account deficits provide the Dollars usedby the Chinese to buy the safest Dollar asset in the world—US Treasuries.

To beclear: the US Dollar probably will not remain the world’s reserve currency.From the US perspective, that might be a disappointment. In the long view ofhistory, it is inconsequential. There is little doubt that China will becomethe world’s biggest economy. Its currency is a likely candidate forinternational currency reserve, but that is not a foregone conclusion—norsomething to be feared.

Response to Comments on Blog #33: MMT and Inequality

OK there really were only two themes inthe comments: first a question about sovereign vs nonsovereignissuers of IOUs and second questions about the MMT position oninequality.

The first has been dealt with all alongin the MM Primer. The sovereign chooses the unit of account, taxes inthat unit and issues IOUs in that unit that can be used to payobligations to the sovereign. Q. E. D.

On the second: MMTers reject the notionthat sovereign government uses taxes to “redistribute” income.No, taxes destroy income. If we want poor people to have income, wegive them jobs and keystroke their bank accounts. If we think richpeople are too rich we can reverse keystroke their bank accounts.

Here’s the problem. I suppose all ofyou looked at Mitt Romney’s (who on earth would name their kidafter a leather implement used in a baseball game?) tax return.Q.E.D. Forget taxes. Ain’t going to reduce wealth of the rich. Intruth, Romney pays way too much in taxes for someone in his incomeclass—remember, he knew he would run for president and so avoidedall questionable evasions. In spite of what the news is nowreporting, most really rich people do not pay taxes. Don’t take myword for it. Bartlett and Steele (two reporters in Philly) got famousfor going through the thousands of pages of the tax code andidentifying thousands of exemptions for well-connected rich folksthat exempted them from paying taxes. They actually figured outexactly who these people were. There were thousands more they couldnot identify—but the exemptions were so specific that it wasobvious they were meant for some favored individual.

Anyway, suppose someone’s income is$20 million a year like Mitt’s (a piker by Bill Gates standards),what tax rate would we need to levy to significantly reduceinequality? Not 30%. Not 70%. 90%? Ain’t never going to happen. Youwill not pass a tax law imposing a rate of 90% much less actuallymake it stick.

So here is what I wrote:

MMTers have written lots on poverty,inequality and the recent massive concentration of wealth income atthe top, so I have no idea where you get the idea that we avoid thesetopics. Indeed, Kelton and I did a detailed study contrasting the Waron Poverty (which did not reduce poverty at all) with the JG/ELRproposal which would have wiped out two-thirds of all poverty even ifthe wage was set at the minimum wage. I have no idea why you belive JG/ELR would lead to massive underemployment–it leads to fullemployment. So far as I can tell, the complaint is that we have notput them in the Primer? That does not mean we have ignored theissued. For those who want to read our study, go here:

“Public Policy Brief No. 78 | June2004

The War on Poverty after 40 Years: AMinskyan Assessment

Twenty to 25 years ago, a debate wasunder way in academe and in the popular press over the War onPoverty. One group of scholars argued that the war, initiated byPresidents Kennedy and Johnson, had been lost, owing to the inherentineffectiveness of government welfare programs. Charles Murray andother scholars argued that welfare programs only encouragedshiftlessness and burdened federal and state budgets.In recent years,despite the fact that the extent of poverty has not significantlydiminished since the early 1970s, the debate over poverty hasseemingly ended. In a country in which middle-class citizens struggleto afford health insurance and other necessities, the problems of theworst-off Americans seem to many remote and less than pressing.Moreover, the welfare reform bill of 1996 has deflected much of thecriticism of the welfare state by ending the individual-levelentitlement to Aid to Families with Dependent Children benefits (nowknown as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) and putting timelimits on welfare recipiency, among other measures.” Download:Public Policy Brief No. 78, 2004 at www.levy.org.And while you are there browsing the Levy pices you will see I wrotemany other pieces on related topics.

So: to reduce inequality, first youstart at the bottom: give jobs. That eliminates 2/3 of all poverty.Then you gradually raise wages over time, by increasing the JG/ELRbasic wage.

And yes, you tackle income at the top.And as some comments indicated, most of the increase of inequality inrecent years is due to the outrageous rewards in the FIRE sector(finance, insurance, real estate). So you must reduce the rewards inthat sector. There is nothing “natural” about such high rewards.They are due largely to government policy. That is not the topichere, but it begins with the fraudsters and then changescompensations, incentives, and rewards. This is not difficultstuff—American management’s rewards are totally out of linecompared with compensation around the globe. And financialinstitutions—where the biggest rewards are—are inherentlypublic-private partnerships.

On progressive taxes, yes I propose acubic-foot-of-dwelling space tax. It is also environmentally sound.

However, we need to understandpolitical economy as well as MMT. First we do not need to”redistribute” from rich to poor. We can give the poor anyincome we want (hint: “keystrokes”) and any income we takefrom the rich goes no where (hint: reverse those keystrokes). So thatis a bogeyman. We can take BMWs away from the rich and give them tothe poor, if you like. But don’t confuse that with taxes—which areimposed in monetary form. Taking BMWs away is confiscation.

Finally, Americans oppose high taxeson the rich. We may not agree with them but it is the truth. In theUS taxes have never “redistributed” income–the rich justavoid and evade taxes and if that doesn’t work they hire Congress togive them loopholes. Forget it, it will not work in America.

Comments Off on Response to Comments on Blog #33: MMT and Inequality

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

MMP #33: Functional Finance and Long Term Growth

Last weekwe examined Milton Friedman’s version of Functional Finance, which we found tobe remarkably similar to Abba Lerner’s. If the economy is operating below fullemployment, government ought to run a budget deficit; if beyond full employmentit should run a surplus. He also advocated that all government spendingshould be financed by “printing money” and taxes would destroy money. That, aswe know, is an accurate description of sovereign government spending—exceptthat it is keystrokes, not money printing. Deficits mean net money creation, throughnet keystrokes. The only problem with Friedman’s analysis is that he did notaccount for the external sector: he wanted a balanced budget at fullemployment, but if a country tends to run a trade deficit at full employment,then it must have a government budget deficit to allow the private sector torun a balanced budget—which is the minimum we should normally expect.

Somehow allthis understanding was lost over the course of the postwar period, replaced by“sound finance” which is anything but sound. It was based on an inappropriateextension of the household “budget constraint” to government. This is obviouslyinappropriate—households are users of the currency, while government is theissuer. It doesn’t face anything like a household budget constraint. How couldeconomics have become so confused? Let us see what Paul Samuelson said, andthen turn to proper policy to promote long term growth.

Functional Finance versus Superstition. The functional finance approach ofFriedman and Lerner was mostly forgotten by the 1970s. Indeed, it was replacedin academia with something known as the “government budget constraint”. Theidea is simple: a government’s spending is constrained by its tax revenue, itsability to borrow (sell bonds) and “printing money”. In this view, governmentreally spends its tax revenue and borrows money from markets in order tofinance a shortfall of tax revenue. If all else fails, it can run the printingpresses, but most economists abhor this activity because it is believed to behighly inflationary. Indeed, economists continually refer to hyperinflationaryepisodes—such as Germany’s Weimar republic, Hungary’sexperience, or in modern times, Zimbabwe—asa cautionary tale against “financing” spending through printing money.

Note thatthere are two related points that are being made. First, government is“constrained” much like a household. A household has income (wages, interest,profits) and when that is insufficient it can run a deficit through borrowingfrom a bank or other financial institution. While it is recognized thatgovernment can also print money, which is something households cannot do, theseis seen as extraordinary behaviour—sort of a last resort. There is norecognition that all spending bygovernment is actually done by crediting bank accounts—keystrokes that are moreakin to “printing money” than to “spending out of income”. That is to say, thesecond point is that the conventional view does not recognize that as theissuer of the sovereign currency, government cannot really rely on taxpayers or financial markets to supply itwith the “money” it needs. From inception, taxpayers and financial markets canonly supply to the government the “money” they received from government. That is to say, taxpayers pay taxes usinggovernment’s own IOUs; banks use government’s own IOUs to buy bonds fromgovernment.

Thisconfusion by economists then leads to the views propagated by the media and bypolicy-makers: a government that continually spends more than its tax revenueis “living beyond its means”, flirting with “insolvency” because eventuallymarkets will “shut off credit”. To be sure, most macroeconomists do not makethese mistakes—they recognize that a sovereign government cannot really becomeinsolvent in its own currency. They do recognize that government can make allpromises as they come due, because it can “run the printing presses”. Yet, theyshudder at the thought—since that would expose the nation to the dangers ofinflation or hyperinflation. The discussion by policy-makers—at least in the US—is far moreconfused. For example, President Obama frequently asserted throughout 2010 thatthe USgovernment was “running out of money”—like a household that had spent all themoney it had saved in a cookie jar.

So how didwe get to this point? How could we have forgotten what Lerner and Friedmanclearly understood?

In a veryinteresting interview in a documentary produced by Mark Blaug on J.M. Keynes,Samuelson explained:

“I think there is an elementof truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced atall times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of thebulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. Theremust be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchisticchaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion wasto scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in away that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief inthe intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] inevery short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say “uh, oh what youhave done” and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that Isee merit in that view.”

The beliefthat the government must balance its budget over some timeframe is likened to a“religion”, a “superstition” that is necessary to scare the population intobehaving in a desired manner. Otherwise, voters might demand that their electedofficials spend too much, causing inflation. Thus, the view that balancedbudgets are desirable has nothing to do with “affordability” and the analogiesbetween a household budget and a government budget are not correct. Rather, itis necessary to constrain government spending with the “myth” precisely becauseit does not really face a budget constraint.

The US (and manyother nations) really did face inflationary pressures from the late 1960s untilthe 1990s (at least periodically). Those who believed the inflation resultedfrom too much government spending helped to fuel the creation of the balancedbudget “religion” to fight the inflation. The problem is that what started assomething recognized by economists and policymakers to be a “myth” came to bebelieved as the truth. An incorrect understanding was developed. Originally themyth was “functional” in the sense that it constrained a government thatotherwise would spend too much, creating inflation. But like many useful myths,this one eventually became a harmful myth—an example of what John KennethGalbraith called an “innocent fraud”, an unwarranted belief that preventsproper behaviour. Sovereign governments began to believe that the really couldnot “afford” to undertake desired policy, on the belief they might becomeinsolvent. Ironically, in the midst of the worst economic crisis since theGreat Depression of the 1930s, President Obama repeatedly claimed that the US governmenthad “run out of money”—that it could not afford to undertake policy that mostbelieved to be desired. As unemployment rose to nearly 10%, the government wasparalysed—it could not adopt the policy that both Lerner and Friedmanadvocated: spend enough to return the economy toward full employment.

Ironically,throughout the crisis, the Fed (as well as some other central banks, includingthe Bank of England and the Bank of Japan) essentially followed Lerner’s secondprinciple: it provided more than enough bank reserves to keep the overnightinterest rate on a target that was nearly zero. It did this by purchasingfinancial assets from banks (a policy known as “quantitative easing”), inrecord volumes ($1.75 trillion in the first phase, with a planned additional $600billion in the second phase). Chairman Bernanke was actually grilled inCongress about where he obtained all the “money” to buy those bonds. He(correctly) stated that the Fed simply created it by crediting bankreserves—through keystrokes. The Fed can never run out “money”; it can affordto buy any financial assets banks are willing to sell. And yet we have thePresident (as well as many members of the economics profession as well as mostpoliticians in Congress) believing government is “running out of money”! Thereare plenty of “keystrokes” to buy financial assets, but no “keystrokes” to paywages.

Thatindicates just how dysfunctional the myth has become.

A Budget Stance to Promote Long Term Growth. The lesson that can be learned fromthat three decade experience of the US is that in the context of a privatesector desire to run a budget surplus (to accumulate savings) plus a propensityto run current account deficits, the government budget must be biased to run adeficit even at full employment. Thisis a situation that had not been foreseen by Friedman (not surprising since theUSwas running a current account surplus in the first two decades after WWII). Theother lesson to be learned is that a budget surplus (like the one PresidentClinton presided over) is not something to be celebrated as anaccomplishment—it falls out of an identity, and is indicative of a privatesector deficit (ignoring the current account). Unlike the sovereign issuer ofthe currency, the private sector is a user of the currency. It really does facea budget constraint. And as we now know, that decade of deficit spending by theUSprivate sector left it with a mountain of debt that it could not service. Thatis part of the explanation for the global financial crisis that began in the US.

To be sure,the causal relations are complex. We should not conclude that the cause of the private deficit was the Clinton budget surplus; and we should not conclude thatthe global crisis should be attributed solely to US household deficit spending. Butwe can conclude that accounting identities do hold: with a current accountbalance of zero, a private domestic deficit equals a government surplus. And ifthe current account balance is in deficit, then the private sector can run asurplus (“save”) only if the budget deficit of the government is larger thanthe current account deficit.

Finally,the conclusion we should reach from our understanding of currency sovereigntyis that a government deficit is more sustainable than a private sector deficit—thegovernment is the issuer, the household or the firm is the user of thecurrency. Unless a nation can run a continuous current account surplus, thegovernment’s budget will need to be biased to run deficits on a sustained basisto promote long term growth.

However, weknow from our previous discussion that fiscal policy space depends on theexchange rate regime—the topic of the next blog.

Further, wewant to be clear: the appropriate budget stance depends on the balance of theother two sectors. A nation that tends to run a current account surplus can runtighter fiscal policy; it might even be able to run a sustained governmentbudget surplus (this is the case in Singapore—which pegs its exchangerate, and runs a budget surplus because it runs a current account surplus whileit accumulates foreign exchange). A government budget surplus is alsoappropriate when the domestic private sector runs a deficit (given a currentaccount balance of zero, this must be true by identity). However, for thereasons discussed above, that is not ultimately sustainable because the privatesector is a user, not an issuer, of the currency.

Finally, we must note that it is not possible for all nations to runcurrent account surpluses—Asian net exporters, for example, rely heavily onsales to the US, which runs a current account deficit to provide the Dollarassets the exporters want to accumulate. We conclude that at least somegovernments will have to run persistent deficits to provide the net financialassets desired by the world’s savers. It makes sense for the government of thenation that provides the international reserve currency to fill that role. Forthe time being, that is the US government.

Response to blog #32: Friedman’s Functional Finance Approach

Thanks for comments and questions. As I had alreadyintervened, I addressed the main points related to this week’s blog already.Let me pick up a few loose ends, and reformat my earlier response.

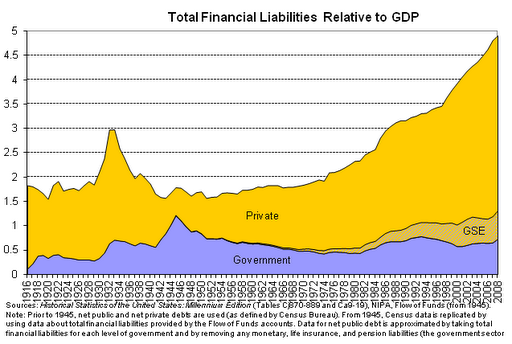

Q1: When you said US Debt/GDP reached 500% was that allprivate debt? And how can the private sector get out of debt?

A: No. Here’s the data break-down. You can see that it iscertainly private debt that has exploded, however. This ends in 2008, and afterthe GFC hit and the US slowed down, government debt started growing rapidly andprivate debt came down a bit as a percent of GDP so it would look a bitdifferent today.

How does the private sector get out of debt? If GDP andincome grow, households can service more debt all else equal, and the ratiowill decline. They can pay off debt. And yes they can default. Note how sharplythe debt ratio came down after the Great Depression—as all 3 of those thingshappened. The most important was economic growth fueled by government spending(and record govt deficits of 25% of GDP during WWII). It can also go down as theeconomy uses export-led growth but for the US that is not likely. The best waywould be to ramp up government spending today.

Q2: Several questions on US current account deficits,foreign accumulation of US Dollar assets, and so on. Also on the Bretton WoodsSystem.

A: I have discussed that a bit previously and we’ll do a lotmore of it in coming weeks—so let’s hold off. With respect to BW: it was amistake. Failed. Worked in the beginning because ROW needed US exports afterWWII and US lent dollars so they could buy them (Marshall Plan). More coming inthe MMP on exchange rate regimes. But briefly, both the BW system and theSterling system (pre WWI) failed. Such international pegged systems do notwork—they always generate crises and then collapse.

Q3: Didn’t Clinton announce he would retire the debt? Did hebelieve it?

A: Yes Clinton appeared on TV and announced all govt debtwould be retired. Who knows or cares what he believed? I think it was Rubin whopushed the idea. But what matters is that all Democrats after him think thatwas the right thing to do, and claim Bush Jr blew it by not continuing with thesurpluses. And so they want to bring back the good old Clinton-Rubin policy assoon as they can get through this crisis! They learned no lessons from thedeath of Goldilocks. Clinton’s tight fiscal policy killed her deader thanElvis.

Q4: Didn’t budget deficits of big-spending Democrats in the1960s cause high inflation?

A: Deficits of the 60s were miniscule. Don’t take my word for it. You can checkit out. Until Obama, no Democratic administration ran big deficits after WWII.Again, check it out. Yes there was some inflation in the late 60s. Big warsusually do generate some—but the war against Viet Nam plus the wimpy and failed“War on Poverty” did not create big deficits because the economy grew fastenough to generate tax revenue. Republicans have always had the biggestdeficits—not necessarily due to big spending, but due to their rotteneconomies that do not grow. Coincidence? Me thinks not.

Q5: Don’t you accept the dollar because you can convert itto gold?

A: Hah: I’ve never done so and would never consider it. Goldis a fool’s gamut. We all accept Dollars because there is a tax system thatrequires them.

Q6: Later Friedman said inflation results from excessivemoney supply.

A: Yes, and he was wrong then and he’s still wrong. Hisfunctional finance paper is probably the only thing he ever got right. Andnobody reads it!

Comments Off on Response to blog #32: Friedman’s Functional Finance Approach

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

MMP BLOG #32: MILTON FRIEDMAN’S VERSION OF FUNCTIONAL FINANCE: A PROPOSAL FOR INTEGRATION OF FISCAL AND MONETARY POLICY

In thecontext of today’s conventional wisdom about the dangers of budget deficits,Lerner’s views (examined last week) appear somewhat radical. What is surprisingis that they were not all that radical at the time. As everyone knows, MiltonFriedman was a conservative economist and a vocal critic of “big government”and of Keynesian economics. No one has more solid credentials on the topic ofconstraining both fiscal and monetary policy than Friedman. Yet, in 1948 hemade a proposal that was almost identical to Lerner’s functional finance views.On one hand, this demonstrates how far today’s debate has moved away from aclear understanding of the policy space available to a sovereign government,but also that Lerner’s ideas must have been “in the air”, so to speak, widelyshared by economists across the political spectrum. At the end of thissubsection we will also visit Paul Samuelson’s comment on this topic—whichprovides a cogent explanation for today’s confusion about fiscal and monetarypolicy. As Samuelson hints, the confusion was purposely created in order tomystify the subject.

Briefly,Milton Friedman’s 1948 article, “AMonetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability” put forward aproposal according to which the government would run a balanced budget only atfull employment, with deficits in recession and surpluses in economic booms.There is little doubt that most economists in the early postwar period sharedFriedman’s views on that. But Friedman went further, almost all the way toLerner’s functional finance approach: all government spending would be paid forby issuing government money (currency and bank reserves); when taxes were paid,this money would be “destroyed” (just as you tear up your own IOU when it isreturned to you). Thus, budget deficits lead to net money creation. Surpluseswould lead to net reduction of money.

He thusproposed to combine monetary policy and fiscal policy, using the budget tocontrol monetary emission in a countercyclical manner. (He also would haveeliminated private money creation by banks through a 100% reserverequirement–an idea he had picked up from Irving Fisher and Herbert Simons inthe early 1930s–hence, there would be no “net” money creation byprivate banks. They would expand the supply of bank money only as theyaccumulated reserves of government-issued money. We will not address this partof the proposal.) This stands in stark contrast to later conventional views(such as those associated with the ISLM model taught in textbooks) that“dichotomized monetary and fiscal policy. Friedman, too, later argued that thecentral bank ought to control the money supply, delinking in his later work theconnection between fiscal policy and monetary policy. But at least in this 1948paper he clearly tied the two in a manner consistent with Lerner’s approach.

Friedmanbelieved his proposal results in strong counter-cyclical forces to helpstabilize the economy as monetary and fiscal policy operate with combinedforce: deficits and net money creation when unemployment exists; surpluses andnet money destruction when at full employment. Further, his plan forcountercyclical stimulus is rules-based, not based on discretionary policy—itwould operate automatically, quickly, and always at just the right level. As iswell known, he later became famous for his distrust of discretionary policy,arguing for “rules” rather than “authorities”. This 1948 paper provides a neatway of tying policy to rules that automatically stabilize output and employmentnear full employment.

We see thatFriedman’s “proposal” is actually quite close to a description of the waythings work in a sovereign nation. When government spends, it does so bycreating “high powered money” (HPM)–that is, by crediting bankreserves. When it taxes, it destroys HPM, debiting bank reserves. A deficitnecessarily leads to a net injection of reserves, that is, to what Friedmancalled money creation. Most have come to believe that government finances itsspending through taxes, and that deficits force the government to borrow backits own money so that it can spend. However, any close analysis of the balancesheet effects of fiscal operations shows that Friedman (and Lerner) had itabout right.

But if thatis so, why do we fail to maintain full employment? The problem is that theautomatic stabilizers are not sufficiently strong to offset fluctuations ofprivate demand. Below we will examine why that is the case.

Note thatFriedman would have had government deficits and, thus, net money emission solong as the economy operated below full employment. Again, that is quite closeto Lerner’s functional finance view, and as discussed above it was a commonview of economists in the early postwar period. But almost no respectableeconomist or politician will today go along with that on the belief it would beinflationary and/or would bust the budget. Such is the sorry state of economicseducation today. How did we get to this point? In last week’s blog, Samuelsonexplained that the belief that the government must balance its budget over sometimeframe a “religion”, a “superstition” that is necessary to scare thepopulation into behaving in a desired manner. Otherwise, voters might demandthat their elected officials spend too much, causing inflation. Thus, the viewthat balanced budgets are desirable has nothing to do with “affordability” andthe analogies between a household budget and a government budget are notcorrect. Rather, it is necessary to constrain government spending with the“myth” precisely because it does not really face a budget constraint.

A Budget Stance for Economic Stability. In Friedman’s proposal, the sizeof government would be determined by what the population wanted government toprovide. Tax rates would then be set in such a way so as to balance the budgetonly at full employment. Obviously that is consistent with Lerner’s approach—ifunemployment exists, government needs to spend more, without worrying aboutwhether that generates a budget deficit. Essentially, Friedman’s proposal is tohave the budget move countercyclically so that it will operate as an automaticstabilizer. And, indeed, that is how modern government budgets do operate:deficits increase in recessions and shrink in expansions. In robust expansions,budgets even move to surpluses (this happened in the US during theadministration of President Clinton). Yet, we usually observe that these swingsto deficits are not sufficiently large to keep the economy at full employment.The recommendations of Friedman and Lerner to operate the budget in a mannerthat maintains full employment are not followed. Why not? Because the automaticstabilizers are not sufficiently strong.

To build in sufficient countercyclical swingsto move the economy back to full employment requires two conditions. First,government spending and tax revenues must be strongly cyclical–spending needsto be countercyclical (increasing in a downturn), and taxes pro-cyclical(falling in a downturn). One way to make spending automatically countercyclicalis to have a generous social safety net so that transfer spending (onunemployment compensation and social assistance) increases sharply in adownturn. Alternatively, or additionally, tax revenues also need to be tied toeconomic performance–progressive income or sales taxes that movecountercyclically.

Second,government needs to be relatively large. Hyman Minsky (1986) used to say thatgovernment needs to be about the same size as overall investment spending–orat least, swings of the government’s budget have got to be as big as investmentswings, moving in the opposite direction. (This is based on the belief thatinvestment is the most volatile component of GDP. This includes residentialreal estate investment, which is an important driver of the business cycle inthe US. The idea is that government spending needs to swing sufficiently and inthe opposite direction to investment in order to keep national income andoutput relatively stable; that, in turn will keep consumption relativelystable.) According to Minsky, government was far too small in the 1930s tostabilize the economy–even during the height of the New Deal, the federalgovernment was only 10% of GDP. Today, all major OECD nations probably have agovernment that is big enough, although some developing countries probably havea government that is too small by this measure. Based on current realities, itlooks like the national government should range from the US low of less than20% of GDP to a high of 50% in France. The countries at the low end of therange need more automatic fluctuation built into the budget than those with abigger government.

Looking tothe decade of the 1960s in the US, one sees that it was more-or-less consistentwith Friedman’s proposal and with Lerner’s functional finance approach. Federalgovernment spending averaged around 18-20% of GDP, and deficits averaged $4 or$5 billion a year, except for 1968 when they temporarily increased to $25billion–but for the decade, deficits ran well under 1% of GDP on average. Wecould quibble about whether the US was at full employment in the 1960s, but itwas certainly closer to full employment during that decade than it was afterthe early 1970s. From the early 1970s until the boom of the 1990s during thepresidency of Bill Clinton, the budget was too tight relative to therecommendations of Friedman and Lerner. How do we know? Because unemploymentwas chronically too high—even in expansions it never got down to 1960s levels.

Note thatthis was not because government spending fell much, or because taxes wereraised. Indeed, the deficit tended to be much higher after the early 1970s (thehigh unemployment period) than it was during the 1960s (the low unemploymentperiod).

What went wrong? Briefly, the problem could be attributed tothe evolution of the international position of the US that led to a chroniccurrent account deficit. The US emerged from WWII in a dominant position—notonly was the dollar in high demand, but so were US exports—needed bywar-ravaged Europe and Japan. The US had a trade surplus, and lent Dollars tothe rest of the world to buy its output. That added to US demand and—from ouraccounting identities—kept our budget deficits small and let our private sectorrun surpluses (save).

Recall thatthe international monetary system (Bretton Woods) was based on a dollar-goldstandard, with exchange rates fixed to the Dollar and the Dollar convertible togold. By the early 1970s, the US was running a trade deficit and foreignholders were exchanging excess dollars for gold. To make a long story short,the US abandoned gold, the Bretton Woods system collapsed, and most developedcountries floated. The dollar fell in value (helping to generate inflationpressures in the US as imports, especially oil, got more expensive), and the USfound it harder to compete in international markets (Japan and Europe hadlargely recovered and were producing for their own markets—and even for the USconsumer). The current account deficit turned negative—more or lesspermanently–during the administration of President Reagan. As we know from ourmacro identities, that deficit would have to be offset by a growing budgetdeficit—which had to be large enough to offset both the current account as wellas the US domestic sector surplus (saving of households and firms). By the endof the 1980s, Congress and the new president (George Bush) agreed to try toreign-in deficit spending. Hence, an already too-small budget deficit (giventhe current account deficit and the desire of the domestic private sector torun surpluses, demand was too low to eliminate unemployment) was constrainedfurther by the Gramm-Rudman Amendment that promised to work toward a budgetbalance.

The economysuffered from weak growth and relatively high unemployment over most of thisperiod. Then, suddenly, economic growth picked up speed during the Clintonadministration; indeed it grew so fast that it produced a budget surplus (astax revenues boomed) that lasted for nearly three years (the first sustainedsurplus since 1929!). President Clinton actually predicted at the time that thebudget surplus would continue for at least 15 more years, and that alloutstanding Federal government debt would be retired (for the first time since1837).

Note thatthis was not accomplished by reversing the current account deficit—whichactually grew. How could the US run a current account deficit and a government budget surplus? Only byrunning a sustained private sector deficit. Indeed, from 1996 until 2007 the USprivate sector ran a budget deficit every year except during the recession ofthe early 2000s. At times, the domestic private sector deficit reached 6% ofGDP (meaning that for every Dollar of US national income, the private sectorspent $1.06. With such a large “flow” deficit, the stock of private sector debt grewrapidly—both in nominal terms and as a ratio to GDP. By 2007, total US debtreached five times GDP (versus three times GDP in 1929 on the verge of theGreat Depression). This huge debt implied a big debt burden—the portion ofincome that had to be devoted to servicing debt. When the economy collapsed in2007, a private sector surplus finally returned (the turn-around from private deficitsto private surpluses amounted to 8% of GDP—a huge reversal that removedapproximately $1 trillion of spending from the economy)—and the governmentbudget deficit grew rapidly to 10% of GDP. Even as the private sector cut downits spending, it was forced to default on debts run up since the Clintonperiod. A wave of bankruptcies and home foreclosures resulted that drove theeconomy into a deep recession and financial crisis that spread around theworld.

Next week: a budget stance to promote growth.

Responses to Blog #31: Functional Finance

All: thanks to some for attempts to come up with some realworld JG jobs suggestions in answer to my challenge last week. We will move onto the JG after dealing with a few more issues related to JG. Keep thinking! Ialso saw that Neil has done a good job around the blogosphere defending JG.Keep it up!

We are more than half-way through the MMP. My responses toquestions/comments are going to become more focused. In part because manyquestions concern issues we already covered, or those we will cover. But moreimportantly, I’ve put a lot of work to the side to do the Primer over the past6+months and now must catch up with a variety of other work and deadlines. So,the Primer will continue, maybe with fewer side issues, but my responses willbe more focused on those questions/comments that respond to the current week’sblog.

So just a few responses today.

Q1: I thought it was the MMT position that adjustments tothe interest rate are not and cannot be matters of open market purchases, whichare only used defensively to maintain the target rate. Instead, the Fedchanges interest rates by announcing the new rate (it’s unclear to me what theactual threat is for the rate to change) or paying IOR at the target rate(unless this is the threat???).

A: That is pretty much what the blog says and what Lernerthought. If banks are short reserves, they drive fed funds rate (in US) abovetarget, Fed buys bonds (OMP), provides reserves, increases the ratio ofreserves/bonds. Just like Lerner (and I) said. On the other hand, when Fedannounces new interest rate target (say, increase from 1% to 2%) it does notneed to change Res/Bonds ratio at all since it is likely banks have the ratiothey want and the demand for reserves is not interest elastic. So I thinkyou’ve confused two different things—using bond sales/purchases to satisfyprivate sector demands for high powered money (to hit a rate target), versusannouncing a new interest rate target (which normally does not require any openmarket sales or purchases).

Q2: What is the government budget constraint?

A: OK this is the idea that even sovereign currency-issuinggovernment is subject to a spending constraint. I’m sure BillyBlog has writtenon this. It came to life in the late 1960s—government is like a household andmust “finance” its spending: taxes, borrowing, or (unlike households) printingmoney. But that is false. Government spends through keystrokes. Yes it canself-impose budget constraints (ie in the US we pass a budget and we alsoimpose a debt limit). But this is nothing like a household, that faces a marketimposed constraint.

Q3: What drove inflation?

A: This is not the time for that. We already talked abouthyperinflation and a bit about CPI inflation. We might return to it againlater; and note that the JG is a price stabilizer. We can have full employmentwithout stoking inflation pressure—a topic for later.

Q4: Can the Euro nations create net financial assets?

A: I already discussed this. Domestically, yes, in the sensethat claims on the Greek government are net financial assets for thenongovernment sector. But I do take the point that ultimately Greece (etc) areusers of the currency so it all depends on the ECB to create true NFA for thesystem as a whole. (or the US which can create NFA in dollars for Eurolandersto hold)

MMP Blog #31: FUNCTIONAL FINANCE: Monetary and Fiscal Policy for Sovereign Currencies

This weekwe begin a new topic: functional finance. This will occupy us for the nextseveral blogs. Today we will lay out Abba Lerner’s approach to policy. In the1940s he came up with what he called the functional finance approach to policy.In one of those amazing historical coincidences, Lerner happened to teach atUMKC when he published one of his most famous papers, laying out the approach.Maybe there is something special in the air in Kansas City?

Lerner’s Functional Finance Approach. Lerner posed two principles:

First Principle: if domestic income is too low, governmentneeds to spend more. Unemployment is sufficient evidence of this condition, soif there is unemployment it means government spending is too low.

Second Principle: if the domestic interest rate is too high, itmeans government needs to provide more “money”, mostly in the form of bankreserves.

The idea ispretty simple. A government that issues its own currency has the fiscal andmonetary policy space to spend enough to get the economy to full employment andto set its interest rate target where it wants. (We will address exchange rateregimes later; a fixed exchange rate system requires a modification to thisclaim.) For a sovereign nation, “affordability” is not an issue—it spends bycrediting bank accounts with its own IOUs, something it can never run out of.If there is unemployed labor, government can always afford to hire it—and by definition,unemployed labor is willing to work for money.

Lernerrealized that this does not mean government should spend as if the “sky is thelimit”—runaway spending would be inflationary (and, as discussed many times inthe MMP, it does not presume that government spending won’t affect the exchangerate). When Lerner first formulated the functional finance approach (in theearly 1940s), inflation was not a major concern—the US had recently livedthrough deflation in the GreatDepression. However, over time, inflation became a serious concern, and Lernerproposed a form of wage and price controls to constrain inflation that hebelieved would result as the economy nears full employment. Whether or not thatwould be an effective and desired way of attenuating inflation pressures is notour concern here. The point is that Lerner was only arguing that governmentshould use its spending power with a view to moving the economy toward fullemployment—while recognizing that it might have to adopt measures to fight inflation.

Lernerrejected the notion of “sound finance”—that is the belief that government oughtto run its finances as if it were like a household or a firm. He could see noreason for the government to try to balance its budget annually, over thecourse of a business cycle, or ever. For Lerner, “sound” finance (budgetbalancing) was not “functional”—it did not help to achieve the public purpose(including, for example, full employment). If the budget were occasionallybalanced, so be it; but if it never balanced, that would be fine too. He alsorejected any attempt to keep a budget deficit below any specific ratio to GDP,as well as any arbitrary debt to GDP ratio. The “correct” deficit would be theone that achieves full employment.

Similarlythe “correct” debt ratio would be the one consistent with achieving the desiredinterest rate target. This follows from his second principle: if governmentissues too much debt, it has by the same token issued too few bank reserves andcash. The solution is for the treasury and central bank to stop selling bonds,and, indeed, for the central bank to engage in open market purchases (buyingtreasuries by crediting the selling banks with reserves). That will allow theovernight rate to fall as banks obtain more reserves and the public gets morecash.

Essentially,the second principle just says that government ought to let the banks,households, and firms achieve the portfolio balance between “money” (reservesand cash) and bonds desired. It follows that government bond sales are notreally a “borrowing” operation required to let the government deficit spend.Rather, bond sales are really part of monetary policy, designed to help thecentral bank to hit its interest rate target. All of that is consistent withthe modern money view advanced previously.

Functional Finance versus Superstition. The functional finance approach ofLerner was mostly forgotten by the 1970s. Indeed, it was replaced in academiawith something known as the “government budget constraint”. The idea is also simple:a government’s spending is constrained by its tax revenue, its ability toborrow (sell bonds) and “printing money”. In this view, government reallyspends its tax revenue and borrows money from markets in order to finance ashortfall of tax revenue. If all else fails, it can run the printing presses,but most economists abhor this activity because it is believed to be highlyinflationary. Indeed, economists continually refer to hyperinflationaryepisodes—such as Germany’s Weimar republic, Hungary’s experience, or in moderntimes, Zimbabwe—as a cautionary tale against “financing” spending throughprinting money.

Note thatthere are two related points that are being made. First, government is“constrained” much like a household. A household has income (wages, interest,profits) and when that is insufficient it can run a deficit through borrowingfrom a bank or other financial institution. While it is recognized thatgovernment can also print money, which is something households cannot do, theseis seen as extraordinary behaviour—sort of a last resort. There is norecognition that all spending bygovernment is actually done by crediting bank accounts—keystrokes that are moreakin to “printing money” than to “spending out of income”. That is to say, thesecond point is that the conventional view does not recognize that as theissuer of the sovereign currency, government cannot really rely on taxpayers or financial markets to supply itwith the “money” it needs. From inception, taxpayers and financial markets canonly supply to the government the “money” they received from government. That is to say, taxpayers pay taxes using government’sown IOUs; banks use government’s own IOUs to buy bonds from government.

Thisconfusion by economists then leads to the views propagated by the media and bypolicy-makers: a government that continually spends more than its tax revenueis “living beyond its means”, flirting with “insolvency” because eventuallymarkets will “shut off credit”. To be sure, most macroeconomists do not makethese mistakes—they recognize that a sovereign government cannot really becomeinsolvent in its own currency. They do recognize that government can make allpromises as they come due, because it can “run the printing presses”. Yet, theyshudder at the thought—since that would expose the nation to the dangers ofinflation or hyperinflation. The discussion by policy-makers—at least in theUS—is far more confused. For example, President Obama frequently assertedthroughout 2010 that the US government was “running out of money”—like ahousehold that had spent all the money it had saved in a cookie jar.

So how didwe get to this point? How could we have forgotten what Lerner clearlyunderstood and explained?

In a veryinteresting interview in a documentary produced by Mark Blaug on J.M. Keynes,Samuelson explained:

“I think there is anelement of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must bebalanced at all times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away oneof the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must bediscipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchistic chaosand inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was toscare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in away that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief inthe intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] inevery short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say “uh, oh what you havedone” and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I seemerit in that view.”

The beliefthat the government must balance its budget over some timeframe is likened to a“religion”, a “superstition” that is necessary to scare the population intobehaving in a desired manner. Otherwise, voters might demand that their electedofficials spend too much, causing inflation. Thus, the view that balancedbudgets are desirable has nothing to do with “affordability” and the analogiesbetween a household budget and a government budget are not correct. Rather, itis necessary to constrain government spending with the “myth” precisely becauseit does not really face a budget constraint.

The US (andmany other nations) really did face inflationary pressures from the late 1960suntil the 1990s (at least periodically). Those who believed the inflationresulted from too much government spending helped to fuel the creation of thebalanced budget “religion” to fight the inflation. The problem is that whatstarted as something recognized by economists and policymakers to be a “myth”came to be believed as the truth. An incorrect understanding was developed.

Originallythe myth was “functional” in the sense that it constrained a government thatotherwise would spend too much, creating inflation and endangering the dollarpeg to gold. But like many useful myths, this one eventually became a harmfulmyth—an example of what John Kenneth Galbraith called an “innocent fraud”, anunwarranted belief that prevents proper behaviour. Sovereign governments beganto believe that the really could not “afford” to undertake desired policy, onthe belief they might become insolvent. Ironically, in the midst of the worsteconomic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s, President Obamarepeatedly claimed that the US government had “run out of money”—that it couldnot afford to undertake policy that most believed to be desired. Asunemployment rose to nearly 10%, the government was paralysed—it could notadopt the policy that Lerner advocated: spend enough to return the economy towardfull employment.

Ironically,throughout the crisis, the Fed (as well as some other central banks, includingthe Bank of England and the Bank of Japan) essentially followed Lerner’s secondprinciple: it provided more than enough bank reserves to keep the overnightinterest rate on a target that was nearly zero. It did this by purchasingfinancial assets from banks (a policy known as “quantitative easing”), inrecord volumes ($1.75 trillion in the first phase, with a planned additional$600 billion in the second phase). Chairman Bernanke was actually grilled inCongress about where he obtained all the “money” to buy those bonds. He(correctly) stated that the Fed simply created it by crediting bankreserves—through keystrokes. The Fed can never run out “money”; it can affordto buy any financial assets banks are willing to sell. And yet we have thePresident (as well as many members of the economics profession as well as mostpoliticians in Congress) believing government is “running out of money”! Thereare plenty of “keystrokes” to buy financial assets, but no “keystrokes” to paywages.

Thatindicates just how dysfunctional the myth has become.

Next week, we’ll show that some Kansas City airmight have drifted northeast to the bastion of free market economics: theUniversity of Chicago

Comments Off on MMP Blog #31: FUNCTIONAL FINANCE: Monetary and Fiscal Policy for Sovereign Currencies

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

Responses to Blog #30: What is Modern Money?

Q1: A fewquick questions:

(1) Isn’t Charles Goodhart essentially a neoclassical who accepts thechartalist approach to money?

(2) Would it be accurate to say the sources of modern chartalism/MMT are:

(a) Mitchell Innes’s work

(b) G. Frederick Knapp’s work

(c) Keynes and Abba Lerner’s functional finance model

(d) Post Keynesianism

(e) some contribution from Minsky? (i.e, FIH)

In this sense it is a new macrotheory sharing many ideas with older PostKeynesians (uncertianty, endogenous money, subjective expectations) but thathas done innovative work in shattering myths about how the central bank andtreasury really function, even though one might argue that Abba Lerner was thetrailblazer in this work:

Lerner, A. P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt,” Social Research10: 38–51

Lerner, A. P. 1944. The Economics of Control, New York, Macmillan.

I’ll just end by saying that when Keynes finally read Lerner’s he appeared toendorse it.

(1) Isn’t Charles Goodhart essentially a neoclassical who accepts thechartalist approach to money?

(2) Would it be accurate to say the sources of modern chartalism/MMT are:

(a) Mitchell Innes’s work

(b) G. Frederick Knapp’s work

(c) Keynes and Abba Lerner’s functional finance model

(d) Post Keynesianism

(e) some contribution from Minsky? (i.e, FIH)

In this sense it is a new macrotheory sharing many ideas with older PostKeynesians (uncertianty, endogenous money, subjective expectations) but thathas done innovative work in shattering myths about how the central bank andtreasury really function, even though one might argue that Abba Lerner was thetrailblazer in this work:

Lerner, A. P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt,” Social Research10: 38–51

Lerner, A. P. 1944. The Economics of Control, New York, Macmillan.

I’ll just end by saying that when Keynes finally read Lerner’s he appeared toendorse it.

A: The first MMT conference I recall was organized by WarrenMosler at Bretton Woods in 1996. At that time, he called it “Soft CurrencyEconomics”, but most of the pieces of the MMT puzzle were there. The 3economists invited by Warren were: Charles Goodhart, Basil Moore, and YoursTruly. I would not accept “essentially neoclassical” as an accuratedescription of Charles. However, to say that he marches to his own drummerwould be accurate! We don’t agree on everything, but we agree on much. A bitmore on that conference: a) the one who actually did the work of organizingWarren’s conference was none other than Pavlina Tcherneva, who at the time wasan undergrad student of Mat Forstater;

b) my memory is notoriously bad and someone will probably correct me byreminding me that the BW conference was not the first meeting of MMT, butit was certainly the first time I met Warren and Pavlina! I think I hadmet Mat before, and had known Stephanie for quite some time; I think I had metBill before 1996–but memory is foggy. I knew all of these people on-line andwe had been working on MMT for several years, but I think the meetings andconferences began in 1996.

b) my memory is notoriously bad and someone will probably correct me byreminding me that the BW conference was not the first meeting of MMT, butit was certainly the first time I met Warren and Pavlina! I think I hadmet Mat before, and had known Stephanie for quite some time; I think I had metBill before 1996–but memory is foggy. I knew all of these people on-line andwe had been working on MMT for several years, but I think the meetings andconferences began in 1996.

Q2: Does Basil J.Moore subscribe to MMT? I know his work on endogenous money. Just to clarify:the founders of MMT are Warren Mosler, Charles Goodhart, Basil Moore, RandallWray, Bill Mitchell, Pavlina Tcherneva, Stephanie A. Kelton and Mat Forstater?Since Basil Moore was obviously a Post Keynesian, is it correct to say thatmany of the founders were influenced by Post Keynesianism ? Does not WarrenMosler have a connection with Paul Davidson? And good old Hyman Minskyinfluenced you, Profesor Wray? Finally here are my brief thoughts on thehistory of MMT: http://socialdemocracy21stcent…

A: Looks good. Look at the first MMP blog which has a list of contributors, andstudents etc that I thank. It is impossible to formulate a complete, definitivelist. Kelton is Bell. Except for my “students” (Tcherneva, Tymoigne,Kaboub, Nersisyan, Leclaire, Fullwiler, Bell, etc, too many to list here)most of us originally met on the old PKT internet discussion group. Others,like Moore and Davidson and Minsky and Kregel are “fathers” in somesense of the PK approach–so I knew them from early 1980s. They accept elementsof MMT, but except for Kregel it probably would not be good to list them asMMTers. We all learned from them. Note I have been negligent in forgetting tolist Ed Nell–and will do so–because he was a supporter from the earliestdays. And he helped to organize meetings at the New School. Minsky is withoutquestion the greatest economist of the second half of the 20thcentury. So, yes, we were influenced.

Q3: Would Henry C. Carey be considered as a kind ofprecursor to MMT? Was he an influence in your intellectual formation?Could this be the source? http://www.amazon.com/Modern-M…

A: Professor Mat Forstater isour resident historian of thought. He might know Carey or this Burstein; thenames do not ring a bell with me.

Q4: John Carney’s piece referring to crony capitalismwas most interesting as was Mitchell’s response talking about the JG. I alsosaw your blog on the JG. These all have a great appeal and I hope you willcomment more. There is no doubt there is just plain corruption when thegovernment tries to stimulate the economy directly but even the JG will besubject to that. I suppose corruption or whatever name you give it exists inall endeavors. The JG has some problems in this world, not least of whichis a base for effective political support. So, again, I hope you willspend some time on those issues. At some point the economics has to come togrips with political power and society.

A: We will deal with most of these issues in coming blogs.But if we all agree on the theory then all we need to do is put our headstogether to make it work. What amazes me is that upward of 95% of theobjections now—20 years later—are about program implementation, politicalfeasibility, and corruption. OK I think some of you are smart. Put your darnedheads together. Stop criticizing. Start solving problems. I cannot see any useof economics or any other branch of human endeavor if it does not try to tackleproblems. Finding useful work for a JG employee seems to me to be on the orderof difficulty as finding a pot for your 2 year old to pee in. If you cannotresolve that problem, you are up the creek without a paddle, so to speak. Haveany of you ever put a diaper on your damned kid? You began as all thumbs andsharp pins. After a few months you could do it with eyes closed, one-handed, ina restaurant while serving your guests with your other hand. As Keynes said,this is like dentistry. Solve the damned problem. Stop complaining. All of you,every single one of you, should be able to resolve all these issues before Ieven start posting blogs about the JG. That’s a challenge. My upcoming posts onJG should be completely redundant. Get your buns in gear. You’ve been here formore than half a year; all the pieces are in place. Go for it. Prizes and fameawait.

MMP Blog #30: What is Modern Money Theory?

Happy New Year to All. We are (I think) a bit over half-waythrough the Modern Money Primer. We should be able to finish it by sometimenext summer.

OK, you might be wondering: Isn’t this a strange point atwhich to raise the question, “what is modern money theory?” Yes, in someimportant ways, it is. However in the past week there have been some reallypretty extraordinary pieces in the popular media trumpeting MMT.

The Economist magazine featured a major story, Heterodox economics, Marginalrevolutionaries: The crisis and the blogosphere have opened mainstreameconomics up to new attack.Of the three heterodox approaches it discussed, one was the “neo-chartalist” or“modern money theory”. Warren Mosler as well as UMKC appeared in the story;indeed, there are two cartoon caricatures featuring Warren adorning the story.

In addition, John Carney at CNBC has been running a seriesof pieces that discusses MMT. This one is particularly good: MMT, NGDP, AndAustrian Economics: Alphabet Noodling!.And here is a link to his previous one:

Further, the debates about MMT continue in the blogosphere,including over at Cullen Roche’s blog: THE FUNDAMENTAL DIFFERENCE BETWEENAUSTRIANS AND MMT’ERS .And a truly excellent piece on Bill Mitchell’s Billyblog: . Bill’spost led to a bit of a scuffle over what is actually in MMT—with Cullen arguingthat the Job Guarantee cannot be acomponent, while Bill insisted that it mustbe. Warren has sided with Bill and written very persuasive comments arguingthat we need the price anchor.

In this Primer we will eventually get to the Job Guarantee,so I do not want to discuss that today. But the arguments made by Cullen haveled to two questions: what is within the realm of MMT? And just where did thename “Modern Money Theory” come from? Indeed, Stephanie Kelton was asked thesecond question and did a bit of investigation. To be sure, we are not sure

.

My 1998 book was entitled “Understanding Modern Money”. WhenI was writing the book, it had a much more boring working title, and I askedMat Forstater and Warren to help think of something catchier. We threw around alot of ideas and rejected all of them. I had in the manuscript the quote I lovefrom Keynes that argues that the State names the money of account and chooseswhat can answer to that name, and has done so “for some four thousand years atleast”. And so I chose to use the term “modern money” to apply only to monetarysystems that have existed for the past “four thousand years at least”. Whatevertype of money that might have existed before that, we cannot be sure. But forthe past 4000 years, at least, we have had State Money—that is, Modern Money. Fromwhence came the book title.

I tended to call our approach the State Money approach inthe early years; perhaps I also used the term Chartalist. That derived from thework of Knapp, who was followed by Keynes in his Treatise on Money (1930). This has usually been misinterpreted,following Schumpeter, as a “legal tender law” approach—a position clearlyrejected by Knapp and Keynes. Both Keynes and Schumpeter knew that it had to bemore than legal tender laws. But that is a matter for another time.

Later, our approach was given the name“neo-Chartalist”—which I think was supposed to be somehow derogatory. After severalof us moved to UMKC, it began to be called “the Kansas City approach”. That ofcourse was misleading because our sister center was in Newcastle under BillMitchell’s direction, and it also ignored the work of Charles Goodhart in theUK; by that time there were already many other people working on the approach,spread around the country and even around the world.

In any event, somehow it got the name Modern Money Theory. Wethink the first time those exact words were used might have been in a commentto Bill’s blog in 2007; if anyone can find that comment or a previous use,please send it along. It also looks like Bill used the term “modern monetarytheory” in an academic paper in 2008.

I decided to look back over my own powerpoints to see how mypresentations of the approach evolved. I’ll provide three. Please bekind—looking at those early ones is a bit painful. But remember that ppt was anew technology back in 2005! And I am still no match for Steve Keen.