By L. Randall Wray

*We’re going to take a break from the regularly-scheduled MMP this week. In its place, I’m posting the keynote talk I gave at Bill Mitchell’s annual Coffee conference in Newcastle. As most of you know, Coffee is the sister center to UMKC’s CFEPS. Some of the participants asked for copies of my talk and I figured some of you might also enjoy it, so am posting it here. It has some of the history of the development of MMT—although it is based on my faulty memory so should not be taken too seriously!

Next week we’ll return to “nonsovereign” currencies.

MMT: A DOUBLY RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSISKeynote: Coffee Conference, University of Newcastle, Australia 2011

As always, I’m happy to be at the annual Coffee conference. I think I’ve attended all of them save one. What a long and at times strange trip it’s been.

Warren Mosler, Bill Mitchell, and I used to meet up just about every year to count the number of people in the world who understood what we were talking about. I remember just a few years ago at Vail, Colorado, we finally got beyond the fingers on two hands.

Now try googling MMT—millions of hits and what is more surprising is that there are blog sites all over the web devoted to MMT, run by people I’ve never heard of. That is a good thing, of course, even if they do not always get things exactly right.

And we’ve got Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong trying to explain what is wrong with MMT even as they “borrow” our ideas. And policy makers including Bernanke spouting off about government spending using keystrokes, sounding like good MMTers. Without attribution.

And it all goes back to PKT (Post Keynesian Thought) in the early 1990s—the first internet discussion group I ever heard of. It started off with all the stars of heterodox economics—Paul Davidson, Herb Gintis, Michael Perelman, Ed Nell; even Hyman Minsky contributed a post or two.

And then there was this strange profane guy named Bill Mitchell who swore like a drunken sailor.

He had little tolerance for Keynes but otherwise I found myself agreeing with him more often than with anyone else. On Kalecki, on Marx, on fiscal policy, and especially against the Austrians that were slowly but surely killing PKT.

And one other guy stood out—a hedge fund manager named Warren Mosler who was continually pushing two things. First there was something he called soft currency economics. It sounded to me like good old Keynesian economics from the Treatise on Money, which followed Knapp’s state theory of money.

And then there was the job guarantee, which I immediately recognized as Minsky’s employer of last resort. I can’t remember what Warren called it but Bill called it BSE, buffer stock employment.

I had never thought of it that way, but Bill’s analogy to commodities price stabilization schemes added an important component that was missing from Minsky: use full employment to stabilize prices. With that we turned the Phillips Curve on its head: unemployment and inflation do not represent a trade-off, rather, full employment and price stability go hand in hand.

Unfortunately, a bunch of cows came down with a disease called BSE and we were forced to search for an alternative name. I never liked ELR, anyway, even though it had a long tradition in the US, at least back to the 1930s. So we tried PSE (public service employment). Bill settled on JG (job guarantee) and that is the one that mostly stuck.

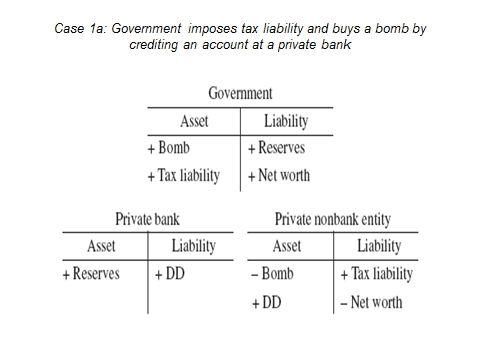

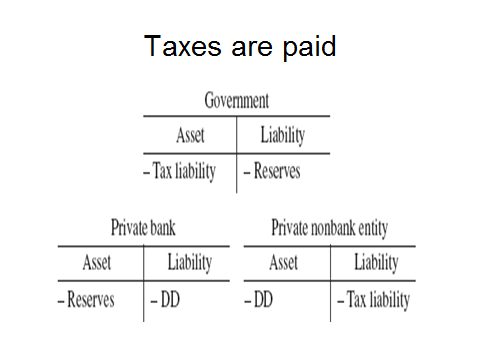

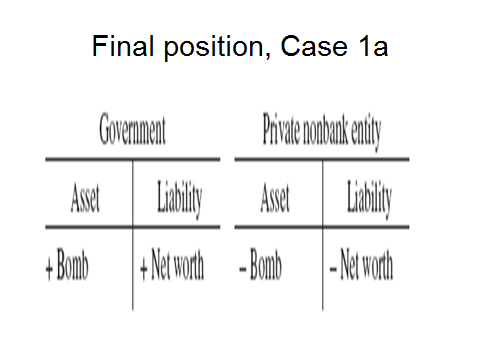

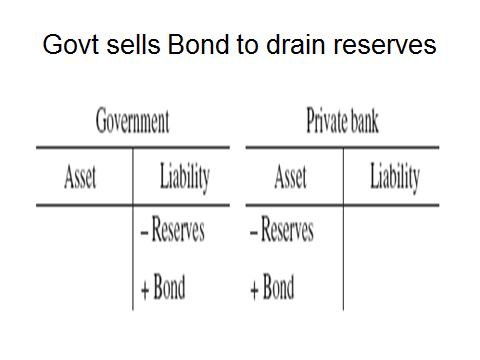

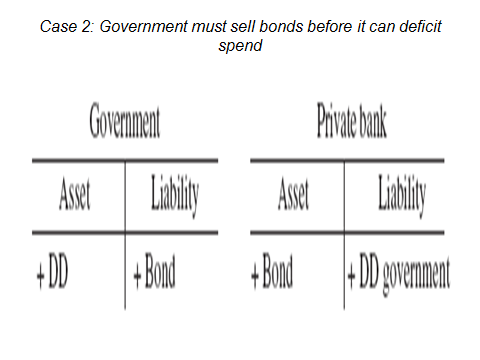

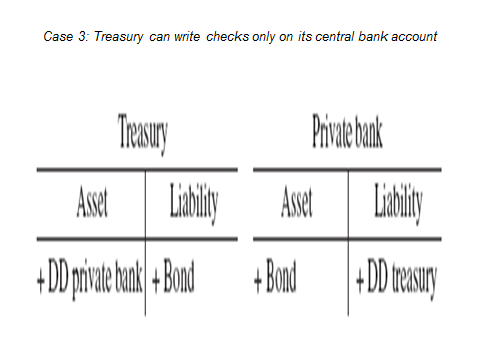

What Warren also added was a much deeper understanding of bank reserves and treasury bonds. I came at this from the PK endogenous money, horizontal reserves view of Basil Moore. There’s nothing seriously wrong with that, but it never understood why a sovereign government would sell bonds. Warren explained bond sales as a reserve drain, and lightbulbs went off. Exactly right: government sells bonds to hit the overnight interest rate target.

I think it was Mat Forstater who brought the final piece of the puzzle: Lerner’s functional finance approach. I don’t think the basic conclusions were new to any of us, but it was nice to find that a rather mainstream economist reached the same conclusion in the 1940s. Affordability is never a proper concern of a sovereign government.

Soon Warren, Bill and I were having discussions off the PKT list. Warren asked to see some of my publications, including a 1990 book. In 1994 he said he wanted to sponsor my next book, giving me an advance against royalties.

I explained to him that economics books don’t earn money. But he argued this one would win me a Nobel Prize. I silently dismissed this as far-fetched and didn’t pursue it. Besides, I had one baby and another soon on the way. No time to write a book.

In 1996 Warren wrote again; he made a generous offer and I protested that there was no way he’d get his money back. It was at that point that I realized that he was not only serious, but seriously rich. I accepted and he bought me out of a semester of teaching. All he wanted in return was the chance to critique draft chapters. Which he did. Sometimes he convinced me; other times I was stubborn. Warren was always tolerant.

And then he invited me to his conference at Bretton Woods in 1996, where I got to help push MMT onto his hedge fund friends. We began to discuss a bigger project, leading to the creation of CFEPS, which eventually ended up at UMKC with Mat joining and later Stephanie Bell/Kelton.

Bill, meanwhile, was setting up COFFEE. I think I came over with Ed Nell and Stephanie and Warren my first time to OZ. And there were meetings in Florida and later the Virgin Islands. With CFEPS and Coffee and then Coffee Europe we had bases for subversion.

And to skip forward a few years, Bill started a blog. I had no idea what a blog was, and thought he was wasting his time. But if we want to credit one thing for spreading MMT all over the planet, it was Bill’s blog. While the academic journals and the policy makers and the mainstream press could mostly ignore us, the blogosphere was wide open to new ideas.

Let me go back to 1997 when I was finishing up my book titled Understanding Modern Money and I sent the manuscript to Robert Heilbroner to see if he’d write a blurb for the jacket. He called me immediately to tell me he could not do it.

As nicely as he could, he said (in the most soothing voice), “Your book is about money—the most terrifying topic there is. And this book is going to scare the hell out of everybody.”

Here we are a decade and a half later and we’re still scaring them. Why? Because nobody wants the truth about money. They want comforting fictions, fantasies, bedtime stories.

To be sure, on the left the story is about the evil Fed and bankers and conspiracies against the poor; on the right it is the evil central bank and government and Free Masons and conspiracies against the rich.

The one thing they seem to be coalescing around is the need for a return to sound money although they don’t necessarily agree on what is sound.

What I want to do today is to argue that both the left and the right as well as economists and policymakers across the political spectrum fail to recognize that money is a public monopoly.

The shared bedtime story told by all sides is that money is a private invention of some clever Robinson Crusoe who tired of the inconveniencies of bartering fish with a short shelf-life for desired coconuts hoarded by Friday.

Self-seeking globules of desire continually reduced transactions costs, guided by an invisible hand that selected the commodity with the best characteristics to function as the most efficient medium of exchange. As everyone from Marxists to Hayekians all know, that turned out to be gold.

Self-regulating markets maintained a perpetually maximum state of bliss, producing an equilibrium vector of relative prices for all tradables, including the gold money that serves as a veiling numeraire.

All was fine and dandy until the evil government interfered, first by reaping seigniorage from monopolized coinage, next by printing too much money to chase the too few goods extant, and finally by efficiency-killing regulation of private financial institutions.

Especially in the US, misguided laws and regulations simultaneously led to far too many financial intermediaries but far too little financial intermediation.

Chairman Volcker delivered the first blow to restore efficiency by throwing the entire Savings and Loan sector into insolvency, and then freeing thrifts to do anything they damn well pleased.

That second blow, deregulation, actually dates to the Nixon years and even before, but it morphed into a self-regulation movement in the 1990s on the unassailable logic that rational self-interest would restrain financial institutions from doing anything foolish.

This was all codified in the Basle II agreement that spread Anglo-Saxon anything goes financial practices around the globe. The final nail in the coffin would be to tie monetary policy-maker’s hands to inflation targeting, and fiscal policy-maker’s hands to balanced budgets to preserve the value of money.

All of this led to the era of Bernanke’s “great moderation”, with financial stability and rising wealth to create Bush’s “ownership society” in which all worthy individuals share in the bounty of self-regulated capitalism.

We know how that story turned out. In all important respects we managed to recreate the exact same conditions of 1929 and history repeated itself with the exact same results.

Take John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Great Crash, change the dates and some of the names and you’ve got the post mortem for our current calamity.

Why do economists get it so wrong? They misunderstand not only the nature of money but also the nature of the market.

It is commonplace to link Neoclassical economics to 18th or 19th century physics with its notion of equilibrium, of a pendulum once disturbed eventually coming to rest. Likewise, an economy subjected to an exogenous shock seeks equilibrium through the stabilizing market forces unleashed by the invisible hand.

The metaphor can be applied to virtually every sphere of economics: from micro markets for fish that are traded spot, to macro markets for something called labor, and on to complex financial markets in synthetic CDOs.

Guided by invisible hands, supplies balance demands and all markets clear.

Armed with metaphors from physics, the economist has no problem at all extending the analysis across international borders to traded commodities, to what are euphemistically called capital flows, and on to currencies, themselves.

Certainly there is a price, somewhere, someplace, somehow, that will balance supply and demand—for the stuff we can drop on our feet to break a toe, and on to the mental and physical efforts of our brethren, and finally to notional derivatives that occupy neither time nor space.

It all must balance, and if it does not, invisible but powerful forces will accomplish the inevitable.

The orthodox economist is sure that if we just get the government out of the way, the market will do the dirty work. Balance. The market will restore it and all will be right with the world.

The heterodox economist? Well, she is less sure. The market might not work. It needs a bit of coaxing. Imbalances can persist. Market forces can be rather impotent. The visible hand of government can hasten the move to balance.

Balance is nice; it’s intuitively appealing. In truth, it was not invented by physics. All cultures view it as natural. It is the universal condition—both in nature and in human society. It reflects an inner yearning for fairness.

As Margret Atwood (Payback) explains, all human and ape societies have recognized the law of reciprocity—you will pay back in this life or the next.

There is an innate notion of equivalent values, and therefore of balances. Animals can tell “bigger than” and they revolt when they are shorted. Even the rat knows it’s not fair. She goes on strike if you try to reduce the reward for running a maze. That violates the rat notion of balance.

There is a right way to do things. Failure to follow tradition upsets the balance. Who knows what wrath imbalance might invoke among the gods.

Gabriel, the Angel of records, keeps God’s ledger book—to be produced in the Last Judgment. Too much imbalance in your life and you go to hell.

And, as we know, Lucifer records the debts—of the souls he will collect. He’ll sell you a good time now, but your soul lies in the balance. You buy now, you pay forever. Sort of like Student Loans in America.

The only things in life you cannot escape are death and taxes. The Devil has a lock on both of those. He’s the tax collector who calls at death. Once your soul is sold, there is no balance. It’s the roach motel—you’ve checked in and you will never get out.

But Christ is the redeemer—he’s a sin eater, repaying your debts to restore balance, to let you sinners get to heaven.

Muslims refer to the scales of justice—your good deeds are weighed against the bad ones. There is a balancing out—if lucky and good, you might just tip the scales.

Much earlier, the God of Time was a Scribe as well as the God of Measurement and Engineering—how would you like that job description? He kept the records, measured worth, and built the scales. At death, he weighed your heart to assess your value.

I suppose you all know that the Pope or Pontiff came out of the engineering gens of one of the Tribes of Rome—that built all the bridges, or ponte, over the Tiber river and followed the example set by the engineers of the Nile by becoming the priestly upper class.

Time. Measurement. Writing. Balance. Everything you need for money and accounting.

And of course none of you is debt-free—original sin ensures that from birth. Can you redeem yourself? Not likely. You need help.

So from time immemorial debts would be periodically cancelled—the Year of Jubilee. With every change of ruler (who of course, was an earthly God of Measurement) or every 7 years or 30 years depending on sinfulness, all debts were cancelled.

Babylonia chose 30 as the likely reign of a ruler; the Bible chose 7—the lucky number, a 7 year ever-normal granary would get you through a drought.

Debt cancellation.

Why? These were no bleeding heart liberals. No, debt cancellation was to restore balance. If all your subjects are in hock to creditors, you cannot rule them. So you eat their sins, redeem their debts, free them and their wives and kids from debt bondage.

Hallelujah!

Now why do we need periodic debt cancellation? The Sotty principle. Compound interest trumps compound growth. As Michael Hudson says, humans recognized this even before they invented writing. The earliest textbooks showed how to calculate compound interest.

It was our first imbalance—our first violation of natural law.

It would inevitably lead to concentration of wealth—like the game of Monopoly, the last player standing would take all. So from Babylonia to Rome, balance was restored by cancelling debts.

Time was circular: time and accounts would reset at zero when the slate was wiped clean.

Time and debt are inherently related. Time compounds the debts at the rate of interest. In Heaven there are no debts and no time; in Hell all debts are compounded forever.

Redemption allows time and debt to start over from balance.

But with Roman Law we abolished circular time, in favor of property law.

Henceforth time moved in one direction only—from a largely known past to what Paul Davidson would call a fundamentally uncertain future. No more debt cancellations.

Just debtor’s prisons—where the debtor would be held until family could redeem him. Later we used prisons and execution simply for retribution—an eye for an eye, a life for a life, so that the scales would balance.

But debtor’s prisons destroyed the balance between creditors and sovereign—just as debt bondage had several thousand years earlier. With the family head in prison, it was impossible to repay. Again, bankruptcy was invented not out of compassion but to restore the balance between the rights of rulers and of creditors.

Yet bankruptcy only allowed a partial reset. It was a poor substitute for Jubilee and Hallelujah. And the creditors ran the show. They liked inequality; they liked imbalance.

As Kenneth Boulding used to say, surveys of the rich consistently show that you cannot imagine how incredibly greedy they are, and how monumentally stupid they are, too. They will gleefully roast the goose that lays the golden egg.

If you do not believe that, you have not been watching Wall Street over the past decade. Or what Germany is doing to Greece and Ireland. When creditors have too much power, they destroy the balance.

So let’s bring this to the present, which is to Modern Money.

Credit and debt are two sides of the same coin. Both creditor and debtor are sinful. They balance. Exactly. The sinful balance is ensured by double-entry book-keeping.

Redemption frees both creditor and debtor. It results in a different balance—one without sin. Bankruptcy also results in balance, but one that maintains the power of creditor over debtor—at least within the limits of law.

But the point is, debts and credits are always in balance. In the private sector, as we always say, inside debts net to zero. Balance.

When we include a government, its IOUs are balanced by credits held by the nongovernment sector. The nongovernment sector’s net credits are claims on government. The government’s deficit means a nongovernment surplus. It balances.

And when we include an external sector, a domestic deficit must be balanced by a foreign surplus. It, too, balances.

There is always financial balance. Imbalance can arise only due to arithmetic errors. Looking at our global mess as a financial imbalance—as almost everyone does—is a mistake.

Our mess is not due to excess liquidity sloshing around the world in the mid 2000s. It is not due to excessive borrowing by America from the Chinese. And it is not due to profligate spending by Mediterraneans with too little self-control.

We need to look at this the way Babylonia’s rulers saw it. The problem is a balance of power, not an imbalance of finance. And to understand this, we’ve got to understand what money is. We need to return to Keynes’s Treatise on Money.

I know I’ve used up more than half my time. But that is OK because many of you have heard me talking about Keynes’s State Theory of Money for the past 20 years. I’ve got nothing new to say about it.

To greatly simplify, money is a measuring unit, originally created by rulers to value the fees, fines, and taxes owed. By putting the subjects or citizens into debt—original sin—real resources could be moved to serve the public purpose. Taxes drive money. This is why money is always linked to sovereign power—the power to command resources.

That power is rarely absolute. It is contested, with other sovereigns but often more important is the contest with domestic creditors. Too much debt to private creditors reduces sovereign power—it destroys the balance of power needed to govern.

Money is not a commodity or a thing. It is an institution, perhaps the most important institution of the capitalist economy. The money of account is social, the unit in which social obligations are denominated.

I trace money to the wergild tradition—that is to say, money came out of the penal system rather than from markets, which is why the words for monetary debts or liabilities are associated with transgressions against individuals and society. A transgressor had to pay a fine to the injured; this prevented “eye for eye” blood feuds.

Eventually, authorities managed to subvert the wergild system so that the fines were paid to the authorities, themselves. And eventually they came up with a measure of the fines, a unit of account in which to compare the incomparable.

And why wait for a transgression before the authority can collect? Enter original sin. We owe taxes for the mere act of being born.

And finally the authority learned it could issue its own IOUs, to purchase what it wanted, while accepting those IOUs in the tax payments. The IOUs of course were denominated in the unit of account—money.

Only the sovereign can impose tax liabilities to ensure its money things will be accepted. Others can issue money things denominated in the sovereign’s money of account—but as they are not sovereign they cannot impose liabilities to ensure their money things are demanded.

But power is always a continuum and we should not imagine that acceptance of non-sovereign money things is necessarily voluntary. We are admonished to be neither a creditor nor a debtor, but all of us are always simultaneously debtors and creditors. It is hard to avoid being simultaneously a creditor and a debtor of a bank! I’m sure that description fits everyone in this room.

Maybe that is what makes us Human—or at least cousins of Chimpanzees, who apparently keep careful mental records of liabilities, and refuse to cooperate with those who don’t pay off debts—what is called reciprocal altruism: if I help you to beat Chimp A senseless, you had better repay your debt when Chimp B attacks me.

Our only advance over Chimps was the development of writing—so we don’t need Elephantine memories to keep track of the credits and debts.

Money predates markets, and so does government. As Karl Polanyi argued, markets never sprang from the minds of higglers and hagglers, but rather were created by authorities.

The monetary system, itself, was invented to mobilize resources to serve what government perceived to be the public purpose.

Of course, it is only in a democracy that the public’s purpose and the government’s purpose have much chance of alignment. In any case, the point is that we cannot imagine a separation of the economic from the political—and any attempt to separate money from politics is, itself, political.

We can think of money as the currency of taxation, with the money of account denominating one’s social liability. I have to deliver a dollar’s worth of commodities—including labor power–to satisfy the public interest.

Often, it is the tax that monetizes an activity—that puts a money value on it for the purpose of determining the share to render unto Caesar.

The sovereign government names what money-denominated thing can be delivered in redemption against one’s social obligation or duty to pay taxes. It can then issue the money thing in its own payments.

That government money thing is, like all money things, a liability denominated in the state’s money of account. And like all money things, it must be redeemed, that is, accepted by its issuer.

It’s not money that the sovereign wants—she wants real resources. Money receipts is the tool, not the goal. If private creditors run the economy there just isn’t enough power to produce left for the sovereign—for the public purpose.

If government emits more in its payments than it redeems in taxes, currency is accumulated by the nongovernment sector as financial wealth.

We need not go into all the reasons (rational, irrational, productive, fetishistic) that one would want to hoard currency, except to note that a lot of the nonsovereign money denominated liabilities are made convertible (on demand or under specified circumstances) to currency. So, many economic units need currency because they’ve agreed to redeem their IOUs for it.

Since government is the only issuer of currency, like any monopoly government can set the terms on which it is willing to supply it. If you have something to sell that the government would like to have—an hour of labor, a bomb, a vote—government offers a price that you can accept or refuse.

Your power to refuse, however, is not that great. When you are dying of thirst, the monopoly water supplier has substantial pricing power.

The government that imposes a head tax can set the price of whatever it is you will sell to government to obtain the means of tax payment so that you can keep your head on your shoulders. Since government is the only source of the currency required to pay taxes, and at least some people do have to pay taxes, government has pricing power.

Of course, it usually does not recognize this, believing that it must pay “market determined” prices—whatever that might mean.

But just as a water monopolist cannot let the market determine an equilibrium price for water, the money monopolist cannot really let the market determine the conditions on which money is supplied.

Rather, the best way to operate a money monopoly is to set the “price” and let the “quantity” float—just like the water monopolist does.

My favorite example is Bill’s buffer stock job guarantee program in which the national government offers to pay a basic wage and benefit package (say $15 per hour plus usual benefits), and then hires all who are ready and willing to work for that compensation.

The “price” (labor compensation) is fixed, and the “quantity” (number employed) floats in a countercyclical manner.

With JG, we achieve full employment (as normally defined) with greater stability of wages, and as government spending on the program moves countercyclically, we also get greater stability of income (and thus of consumption and production).

As Minsky said, anyone can create money (things). I can issue IOUs denominated in the dollar, and perhaps I can make my IOUs acceptable by agreeing to redeem them on demand for US government currency.

The conventional fear is that I will issue so much money that it will cause inflation, hence orthodox economists advocate a money growth rate rule. But it is far more likely that if I issue too many IOUs they will be presented for redemption. Soon I run out of currency and am forced to default on my promise, ruining my creditors.

That is the nutshell history of most private money creation. If you’ve heard of Bear or Lehman or Northern Rock, you know what I mean.

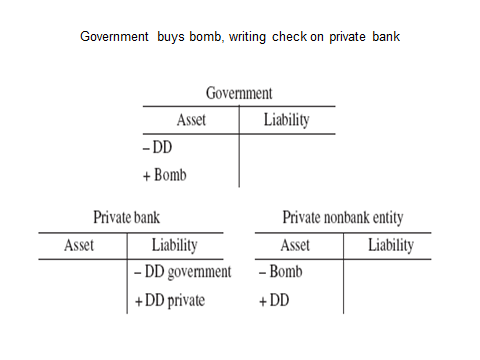

But we have always anointed some institutions with a special relationship, allowing them to act as intermediaries between the government and the nongovernment. Most importantly, government makes and receives payments through them.

Hence, when you receive your Social Security payment it takes the form of a credit to your bank account; you pay taxes through a debit to that account.

Banks, in turn, clear accounts with the government and with each other using reserve accounts (currency) at the central bank, which ensures clearing at par. To strengthen that promise, we introduced deposit insurance so that for most purposes, bank money functions like government money.

Here’s the rub. Bank money is privately created when a bank buys an asset—which could be your mortgage IOU backed by your home, or a firm’s IOU backed by commercial real estate, or a local government’s IOU backed by prospective tax revenues.

But it can also be one of those complex sliced and diced and securitized toxic waste assets you’ve been reading about since 2008. A clever and ethically challenged banker (is there another kind?) will buy completely fictitious “assets” and pay himself huge bonuses for nonexistent profits while making uncollectible “loans” to all of his deadbeat relatives.

The bank money he creates while running the bank into the ground is as good as the government money the Treasury creates serving the public interest. And he will happily pay outrageous prices for assets, or lend to his family, friends and fellow frauds so that they can pay outrageous prices, fueling asset price inflation.

This generates nice virtuous cycles in the form of bubbles that attract more money until the inevitable bust.

The amazing thing is that the free marketeers want to “free” the private financial institutions but advocate reigning-in government on the argument that excessive issue of money by government is inflationary.

Yet we have effectively given banks the power to issue government money (in the form of government insured deposits), and if we do not constrain what they purchase they will fuel speculative bubbles. By removing government regulation and supervision, we invite private banks to use the public monetary system to pursue private interests.

Again, we know how that story ends, and it ain’t pretty. Unfortunately, we now have a government of Goldman, by Goldman, and for Goldman that is trying to resurrect the financial system as it existed in 2006—a self-regulated, self-rewarding, bubble-seeking, fraud-loving juggernaut.

To come nearer to a conclusion: the primary purpose of the monetary monopoly is to mobilize resources for the public purpose.

There is no reason why private, for-profit institutions cannot play a role in this endeavor. But there is also no reason to believe that self-regulated private undertakers will pursue the public purpose.

Indeed, we probably can go farther and assert that both theory and experience tell us precisely the opposite: the best strategy for a profit-seeking firm with market power never coincides with the best policy from the public interest perspective.

And in the case of money, it is even worse because private financial institutions compete with one another in a manner that is financially destabilizing: by increasing leverage, lowering underwriting standards, increasing risk, and driving asset price bubbles.

Unlike my JG example, private spending and lending will be strongly pro-cyclical. All of that is in addition to the usual arguments about the characteristics of public goods that make it difficult for the profit-seeker to capture external benefits.

For this reason, we need to analyze money and banking from the perspective of regulating a monopoly—and not just any monopoly but rather the monopoly of the most important institution of our economy.

Government has an unlimited supply of its own money—but there have to be available productive resources.

In modern economies that is not the usual constraint, however. Government’s sovereign power is constrained in two main ways: arbitrary self-imposed budgetary constraints, and exchange rate constraints.

Many countries happily impose both types—including Euroland. The handcuffs of budget limits were not enough—so they imposed the ball and chain of the Euro. We can observe the fall-out right now.

A sovereign government that issues its own currency faces no inherent financial constraints. It cannot produce a financial imbalance. It can buy any resources that are for sale in terms of its own currency by using keystrokes.

That does not mean it should try to buy all the resources—it can certainly produce inflation and it can leave too little resources to fulfill the private purpose.

Government needs to use its sovereign power to move just the right amount of resources to serve the public purpose while leaving enough for the private purpose. That balance is mostly political. It is hard to find. I admit all that.

But trying to use an arbitrary budget limit or supposed “balance” between tax receipts and monetary spending (over some time period determined by the movement of celestial objects) is the worst possible way I can conceive of trying to find the right balance between the public and private purposes. What it usually does in reality is to leave the resources unused—wasted—rather than to leave them for the private purpose.

Much better is to explicitly decide: what do we want government to do? What do we want our private sector to do? Do we have a sufficient supply of resources domestically plus what we can obtain externally to achieve both? If we don’t how can we expand capacity as needed?

I’m not necessarily arguing for a planned economy as usually defined. But of course, all economies are planned, of necessity. The question is by whom and for whom. Currently, the by and for is Goldman.

These are the real issues, they are difficult, they are contentious. But they have almost nothing to do with the size of a budget deficit. It is worse than pointless to set a deficit ratio goal of 3% or 6%, and a debt ratio goal of 60%. It is counterproductive.

Let me turn to the other self-imposed constraint: pegged exchange rates. Adopting a gold standard, or a foreign currency standard (“dollarization” or “euroization”), or for that matter a Friedmanian money growth rule, or an inflation target is a political act that serves the interests of some privileged group.

There is no “natural” separation of a government from its money. The gold standard was legislated, just as many countries legislate the separation of Treasury and Central Bank functions, and some require balanced budgets or set arbitrary deficit ratios and debt limits. Nothing natural about that.

Ditto the myth of the supposed independence of the modern central bank—this is but a smokescreen to hide the fact that monetary policy is run for the benefit of Wall Street and London and Frankfurt and Paris.

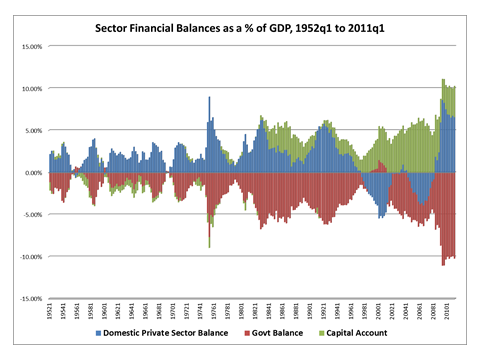

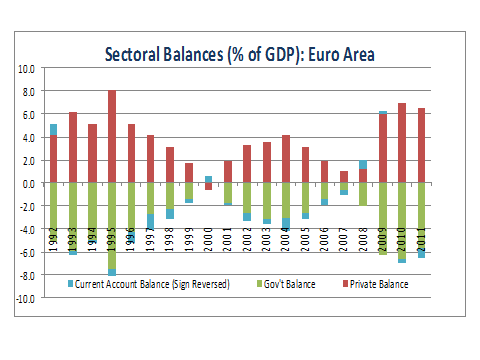

Wynne Godley taught us about balances—the sectoral balances. If you take a look at US sectoral balances across the three sectors, what do you see? Balance. A mirror image.

In normal times, the private sector surplus plus the current account deficit equals the budget deficit. In the abnormal times of private sector deficits, we still saw balance—the government even ran budget surpluses for a few years to maintain the balance.

Take a look at Euroland’s balances; what do you see? Balance.

Isn’t it amazing? Whenever the private sector surplus rises, the budget deficit rises; the correlation is near 100%, with the current account acting as the balancing item.

Financial balances balance.

If you take the world as a whole, there is no external sector since we don’t trade with Martians. And so the sum of the global government deficits equals the sum of the private sector surpluses. It balances.

What’s the problem in Euroland? Power. Private creditors in central Europe have too much of it; Sovereigns on the periphery have too little.

The creditors are starving the member states, aided and abetted by the Euro, which usurped sovereign power and handed it over the banking elite.

But even still, the balances balance. You can curse the moon for its travels but it still is going to circumnavigate the globe.

Admonish the Mediterraneans all you like for their budget deficits, but they still will have them compounded by the German export surpluses.

The real imbalance is power.And this isn’t just a European disease. There is a generalized perception of a world out of balance. We’ve got Arab springs, Occupy Wall Street movements, and protests all over Europe.

Why? Imbalances: everywhere I look in the Western world, the public sector is too small; we’ve privatized too many essential public sector functions—our arts, culture, prisons and punishment, military in Iraq, increasingly our education, our motor vehicle departments. All privatized.

Even responsibility for full employment, and supervision of our banks. We let them self – regulate, and even self-prosecute and self-punish.What happens? Fraud, unemployment, inequality, poverty, and inadequate healthcare, retirement, and welfare.

If you think about it we chose the worst of all possible times to embark on the great Neoliberal experiment—downsizing government, privatizing many of its functions, slashing the safety net. In the West we are aging—which creates the twin problems of the need to devote more resources to aged care and at the same time a private desire to accumulate financial resources for individual retirements.

And that in turn led to the accumulation of unprecedented financial wealth under management by professionals.

Current and future retirees demand higher returns to increase their security and what Minsky called Money Manager Capitalism responded by pouring more resources into the financial sector, doubling its share of value added and capturing 40% of all corporate profits.

It’s too much. Finance is at best an intermediate good that might in the best of circumstances contribute to production. At the same time, financial wealth represents a potential claim on output but does not guarantee output will be available as needed.

We need old folks homes but finance is more interested in gambling on CDOs squared and cubed.

But it is worse than that. Modern finance, at least what is practiced at the biggest banks, is about fraud.

So finance is not even a zero sum game—it largely makes a negative economic contribution.

So the imbalance is one of power. The disease is money manager capitalism. The symptom is the subprime frauds in the US, the austerity imposed on Greece and Ireland, the stagnation of incomes in most developed nations, the rising inequality and poverty in the midst of plenty, the growing despair and feelings of hopelessness.

We are headed into another Global Financial Crisis, and likely into a Great Depression 2.0. We’ve handed the monopoly power over to Wall Street and tied the hands of government.

The Occupy Wall Street protestors have got it right—you’ve got to cut off the head of the beast—the Blood-Sucking Vampire Squid on Wall Street that has completely subverted democracy.

We must have fundamental reform and MMT shines a light on the path we need to take.