By J.D. Alt

Even the most progressive proponents of climate change mitigation frame their argument with the proposition that the “cost” of mitigation today is far less than what the “cost” of climate change will be down the road if we fail to act now. While it sounds compelling, this argument perpetrates a deep confusion about what “cost” means when applied to the idea of inventing, designing and building the carbon-neutral infrastructure and energy systems that climate mitigation will require. This confusion, in turn, makes it more difficult for the political process to make rational decisions.

To illustrate, we need look no further than the recent United Nations IPCC report which, for the first time, not only details the potential catastrophe of climate change by the end of this century, but projects a “cost” for preventing that catastrophe from unfolding. This “cost” is calculated as a percentage of annual global GDP.

Right off the bat, the confusion begins. In some reporting, the IPCC’s projected “cost” of climate mitigation is described as a .06% reduction in global GDP annually. Other analysis state that the “cost” will equal .06% of annual global GDP. Obviously, there’s a significant difference. Reducing GDP means the world will produce less goods and services, employing fewer people to do less stuff—a dire prediction given the current high levels of unemployment world-wide. Saying the “cost” will equal some percentage of global GDP, on the other hand, means that GDP won’t decline, but that some percentage of the goods and services produced by the GDP will be directed towards climate change mitigation. Some of the media explainers—Bloomberg News, for example (whom you’d expect to know better)—included both meanings in a single pair of sentences: Headline: “Climate Protection May Cut World GDP 4% by 2030, UN Says”—and the article’s opening line: “The cost of holding rising temperatures to safe levels may reach 4 percent of economic output by 2030, according to a draft United Nations report.”

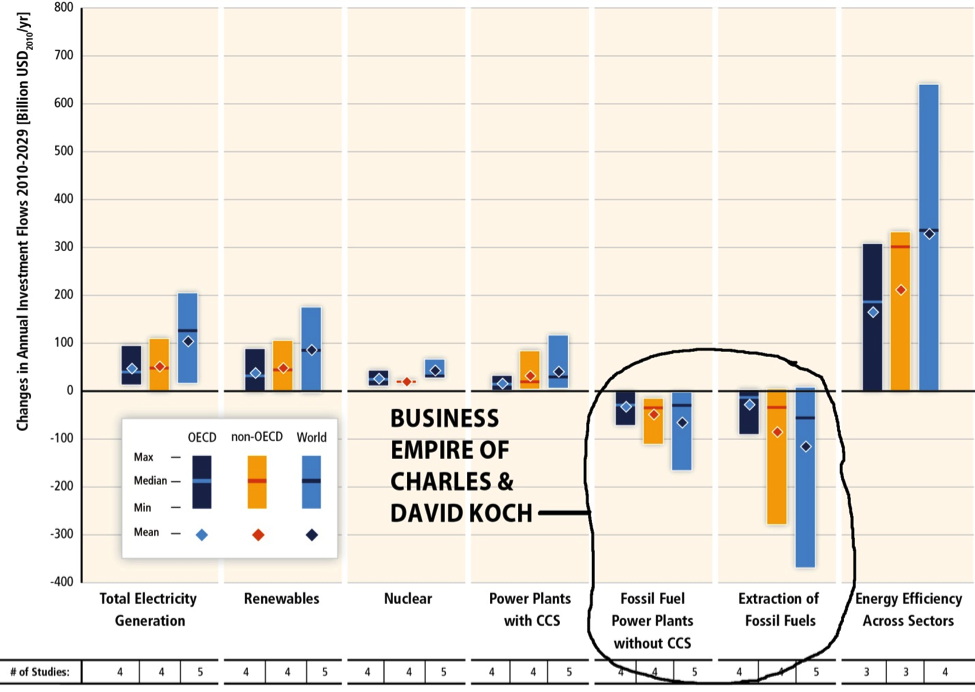

Confusion seems to reign even within the IPCC. A post on the website Real Climate, which is managed by climate scientists themselves, frames it this way: “The IPCC represents the costs (of climate change mitigation) as consumption losses as compared to a hypothetical ‘business-as-usual’ case.” But the IPCC report itself contains a summary chart showing global “Annual Investment Flows 2010-2029” increasing (according to my math, adding up the median projected global numbers) by a potential net gain of approximately $510 billion per year. So how can the “investment flow” increase by $510 billion annually while the world GDP decreases (consumption losses) by 4% between now and 2030?

But the confusion runs even deeper. Even if we accept the fact that the world will have to spend an additional $510 billion annually (instead of being forced to spend $510 billion less), we are led by semantic and political logic to believe we will be “losing” $510 billion every year as a global society. After all, that’s what “cost” means, right?—something you lose, something you no longer have because you’ve paid it out. So our minds resist. We don’t want to have to incur that $510 billion “cost”. We’d rather save the money and take our chances that maybe all these IPCC predictions will prove to be wrong, or that our kids, when they grow up, will figure out a great way to make everything okay again.

The forces aligned against mitigation exploit this confusion at every opportunity. A 4% reduction in global GDP by 2030 proves that climate mitigation “destroys jobs”—a favorite refrain. $510 billion that we have to spend on goods and services for climate mitigation means that much less is available to spend on the goods and services we’re buying today—money “lost” to a cause we’re not 100% sure is even necessary. The more we can convince ourselves we’re “not sure”, the more iffy it becomes to incur that “cost”—hence the strident effort to counter every new climate report with the opinion of some scientist somewhere that seems to refute the scientific evidence.

Then there is this confusion, as expressed by Robert J. Samuelson recently in the Washington Post: “Carbon capture and storage—pumping carbon dioxide emissions from power plants underground—has been discussed for years. So far, it’s not commercially viable.” (Emphasis mine.) So we implicitly assume—as Mr. Samuelson demonstrates—that the infrastructure and carbon-neutral energy systems we’re going to need have to be “commercially viable.” In other words, their development must be market-driven. If the “market” isn’t willing to pay for it, there can’t be any justification for creating it. No doubt the IPCC’s “Changes in Annual Investment Flows” includes a substantial number of electric vehicles and the nation-wide network of public charging stations that will make them convenient and desirable. Until those items become “commercially viable”, however, there’s no reason to expect them to be built because no business is willing to incur the “costs” without the promise of a substantial reward. While Tesla and others have started the inevitable transition, the IPCC report makes clear there isn’t time for the long evolution that radical technology change typically requires. So, we are pretty much left with only the option of prayer—which has the virtue of not “costing” a cent.

If we came to our senses, however, and removed our soot coated “cost goggles”, we’d see the most obvious and simple thing: The $510 billion the IPCC suggests must be spent annually to invent and build carbon-zero infrastructure and energy systems—that money gets paid to somebody in exchange for the doing and the inventing and the building. Who would that be that it gets paid to? Well, it might be you if you got busy and positioned yourself as someone who could usefully contribute in some way to the effort. To say that the “cost” of climate mitigation is .06% of global GDP annually is no different than saying the “cost” of pizza is .06% of global GDP. “Cost”—by the simple logic of accounting—is actually something we, the people, get paid—just like people get paid to make pizza.

This, of course, reveals the ACTUAL point of contention amidst all the confusion: Into whose pockets is the .06% of annual GDP for climate mitigation going to be directed? If you look at the IPCC’s chart of “Changes in Annual Investment Flows” it becomes clear what the strident complaining and foot-dragging is really all about—and understandable with regard to where it’s coming from (see below): Those projected negative investment flows happen to be in the cash-generating business empire owned by Charles and David Koch. That simple fact pretty much sums up the whole American political scene about global warming.

Pingback: J.D. Alt: Climate Mitigation and Confusion About "Cost": Who Benefits? | naked capitalism