I’ve written numerous times already about how a deficit “financed” by bonds vs. “money” doesn’t matter in terms of inflationary effect. Notwithstanding my views there (which are not discussed in this post), the point of this post will be to explore the neoclassical paradigm on this matter, since this is at the core of the recent debate between Steve Randy Waldman (see here, here, and here) and Paul Krugman (see here and here) on the so-called “permanent floor.” (It might be of interest to some that I explained how a “permanent floor” would work back in 2004.)

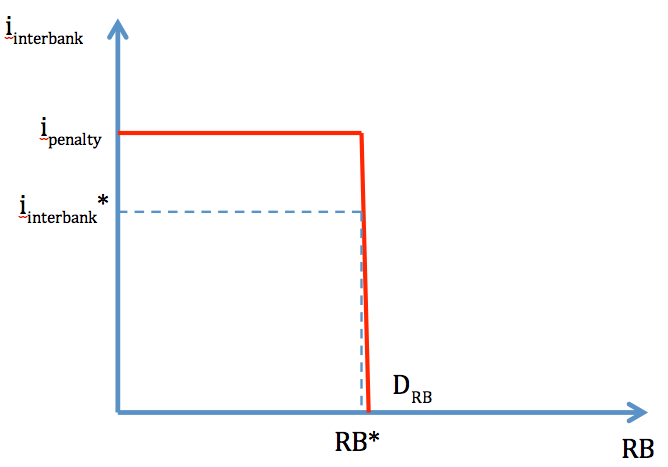

Let’s consider a time at some point in the future at which the Fed has ceased its current near zero interest policy, IOR, and QE’s, and has completed whatever exit strategy was deemed necessary to drain the reserve balances that the various rounds of QE produced. In terms of the federal funds market, it would look much like it did before the crisis, as in Figure 1. The target interbank rate (iinterbank*) is at some positive rate of interest selected by the Fed in accordance with its reaction function, and the Fed has set its penalty rate at some spread above its target rate. The demand for reserve balances is roughly vertical at the quantity banks desire to hold to settle payments and meet reserve requirements (RB* in the graph), as is now recognized even in neoclassical literature. (Post Keynesian endogenous money folks said this for decades; I explained in my 2002 paper why there could logically be no liquidity effect in the federal funds market when the Fed changes its target rate. I’m glad neoclassicals are catching up to us here.) The quantity of reserve balances supplied by the Fed is essentially a vertical supply curve (dotted vertical line) where the Fed simply attempts to accommodate the demand at the target rate, which is well documented in empirical literatures of central banks and also neoclassical economists to be the actual practice of central banks. (I have argued they have no choice but to do this.)

Figure 1—Federal Funds Market Post QE

Now, what if the Fed were to decide to raise the monetary base via QE again? Before answering, let’s recognize that neoclassical economists all seem to believe there are two things that stop QE from “working” in the sense that they stop the money multiplier and/or the quantity theory of money in their tracks. These are the following:

- Interest on reserve balances at the target rate, since they believe this is an opportunity cost to bank lending (see here and here as just two examples of literally dozens; I explained why this is incorrect here)

- Interest rates at the zero bound, since then “money” (i.e., “dead presidents”) and t-bills are now perfect substitutes.

I don’t know the exact proportion that believe in both of these versus just one of them, but I’ve seen enough that it seems most believe in both. Note for #1, reserve balances and t-bills are perfect substitutes there, too, while for #2 the rate paid as interest on reserve balances (zero) would be equal to the prevailing interest rate (zero). So, there’s nearly complete overlap between the two points. In short, in either case, the quantity theory of money now does not run from “money” to inflation, as velocity falls in kind with the increase in “money.”

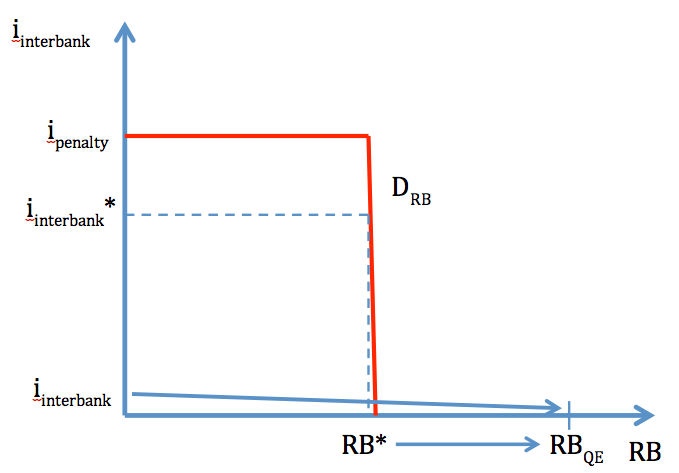

What happens if the Fed starts QE again given the context set in Figure 1? Obviously, the overnight rate falls to zero, since the quantity of reserve balances supplied quickly dwarfs banks’ demand for them (the demand for reserve balances was about $15-$20 billion prior to 2008). This is shown in Figure 2, where there is an increase in reserve balances from RB* to RBQE and iinterbank has fallen to zero. Note that this is just supply and demand—an increase in quantity supplied well in excess of quantity demanded at any price simply leads the price to fall to zero.

Figure 2—Federal Funds Market with QE

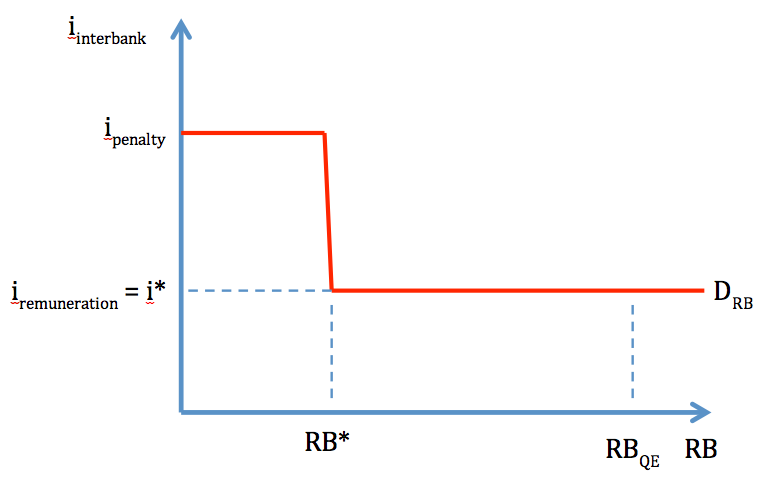

How can we avoid the price falling to zero? We can pay interest on reserve balances, which now becomes the new target rate. This is shown in Figure 3, where the increase in reserve balances to RBQE now results in the interbank rate settling at the rate on reserve balances (iremuneration), which effectively becomes the central bank’s new target rate. Note again that this is just supply and demand—an increase in quantity supplied well beyond the quantity demanded at any price will require a price floor in order to keep the price above zero.

Figure 3—QE with Interest on Reserve Balances

You probably see where this is going now, if you didn’t several steps ago. To actually carry out QE, the Fed must either accept an interest rate target at zero or pay interest at the target rate if it wants an interest rate above zero. But these are precisely the two cases described above for which QE doesn’t work in the neoclassical view. The only other thing the Fed could do would be to reverse the QE and drain all the excess reserve balances, but this simply reverses the QE as if it had never happened.

What if instead the Fed does QE by purchasing treasuries or other securities with “cash?” Note that currently this isn’t operationally possible—the Fed settles all of its transactions on Fedwire, which only settle with reserve balances (and US Treasuries only settle on Fedwire), but let’s play along since at least some neoclassicals think this can actually work. The basic point neoclassicals want to make here is that they believe the Fed can exogenously control the quantity of currency (i.e., “dead presidents”), and thereby generate a “hot potato effect” as the “excess cash balances” created by this form of QE are spent repeatedly by individuals trying to rid themselves of so much cash and hold computers, toothpaste, toasters, new homes, couches, and so forth instead. (Krugman doesn’t explicitly discuss exogenous control over currency in the debate with Waldman, but he did explicitly argue that the Fed could do this here, which I then countered here.)

Unfortunately for neoclassicals, in the real world we have these things called banks (which have still not made it into neoclassical models of the macroeconomy aside from the crude and inapplicable money multiplier model). And banks offer these things called checking accounts, savings accounts, money market accounts, time deposits, and so forth. And individuals that do not want to hold their wealth in the form of cash (i.e., have “excess cash balances”)—QE is, after all, at core a portfolio swap out of Treasuries and into reserve balances, not an increase in income or wealth, or “cash” in this example in which extreme license is being taken with how the Fed actually does things—can costlessly convert their cash into these checking accounts, savings accounts, money market accounts, and time deposits. This conversion occurs at par value as required by law, and it leaves banks holding the “cash” in their vaults while they’ve credited the accounts of their new depositors. This ability to convert is thus also unlimited as crediting the accounts of depositors simply requires changing numbers on a balance sheet and accepting more vault cash (i.e., there is no “limit” to the quantity of deposits that can be created via conversion). (The same process stops any sort of “hot potato effect” that might occur beginning with deposits instead of currency—the ability to costlessly convert undesired balances to savings, time deposits, and so forth is again obvious and unlimited.)

So, what do the banks do with all their new vault cash that is well in excess of what they expect their customers to withdraw? They sell it back to the Fed in exchange for reserve balances, and the currency is now out of circulation. But now there is a large excess of reserve balances—what does the Fed do about that? As above in Figures 2 and 3, it either accepts a zero interest rate or pays interest on reserve balances at its target rate if it wants a non-zero rate. And now we’re right back to points 1 and 2 that are the very things neoclassicals agree stop QE in its tracks. Or, the Fed can sterilize by selling securities to drain the reserve balances, which again just reverses the QE.

What does all this mean?

First, the quantity of currency circulating—“dead presidents”—can never be exogenously controlled in a world in which we have banks (!) that costlessly convert currency to deposits, savings, and so forth, effectively taking the currency out of circulation, which banks then convert to reserve balances. There is no hot potato effect for currency in the real world.

Second, whenever the Fed attempts QE, it must accept a zero interest rate or pay interest at the target rate—the only other choice operationally is to argue that the “laws” of supply and demand have been suspended. Krugman in fact does this when he argues that the Fed could expand the monetary base without sterilizing and also without paying interest on reserves (his option 3); he then claims this would be inflationary while also arguing it would not be inflationary if instead interest were paid on reserves. But from Figures 2 and 3, again, either this leaves the federal funds rate at zero (no sterilization) or at the target rate (interest on reserve balances), and neither of these are inflationary in his own view.

What neoclassicals here can’t seem to accept is what Post Keynesians have known for decades and some New York Fed researchers explained in crystal clear language a few years ago, namely that “the cost of reserves, both intraday and overnight, are policy variables. Consequently, a market for reserves does not play the traditional role of information aggregation and price discovery.” The Fed simply must set a price—it cannot do otherwise. Not setting a price of reserves when it attempts to expand the monetary base simply means setting the price of reserves at zero.

Finally, because neoclassicals believe that a zero interest rate target or interest on reserve balances at the target rate stops QE in its tracks, then they are left with no real-world situations in which these can actually create inflation from within their own paradigm. In other words, unless they are willing to suspend belief in supply and demand, they must suspend belief in QE “working” (at least the quantity effects of QE) in order to be logically and internally consistent.

Pingback: interfluidity » A confederacy of dorks

Pingback: The Coin is Dead! Long Live the Coin! | Monetary Realism

Pingback: Understanding the Permanent Floor—An Important Inconsistency in Neoclassical Monetary Economics « Economics Info

Pingback: Floors and ceilings | Fifth Estate

Pingback: Drop It: You Can Call for Helicopter Money but Drop the Call for "Coordination" | New Economic Perspectives