Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

February 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Tag Archives: William K. Black

The European Central Bank Rises above the Law and its Principles

The European Central Bank (ECB), at the insistence of Germany’s government, was created with a single mission – price stability. Its mono-mission represented an explicit rejection of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s dual mission of price stability and full employment. The usual explanation for this choice is German’s phobia about inflation arising from the searing experience of hyper-inflation during the Weimar Republic. The hyper-inflation discredited the Republic and is often blamed for Hitler’s electoral successes. One must be cautious about this explanation, however, for the demands of the German public did not drive the creation of the ECB. The creation of the euro required the creation of the ECB. Polls showed that had the German public’s policy views prevailed, Germany would have rejected adoption of the euro by a wide margin. German businesses, particularly its banks, pushed Germany to adopt the euro and they made sure that the German public was not permitted to vote on the creation of the euro and Germany’s adoption of the euro.

German banks did not trust Italy and demanded that the EC’s sole mission be preventing inflation (more precisely, any inflation above roughly 0.5 percent annually.) The ECB was to be run strictly along the lines of German Central Bank’s holy war against inflation. Implementing the ECB’s exclusive focus on stopping inflation created a political tension with France, Germany’s partner in running the EU. France successfully demanded that the first head of the ECB serve only half his term and be succeeded by a French official. Germany’s obsession with avoiding even modest inflation, however, was shared by many senior EU central bankers so regardless of nationality, ECB senior bankers have acted as if they were conservative German central bankers.

The ECB praised its mono-mission and asserted its superiority over the U.S. model. The mono-mission was the perfect accompaniment for the rising cult of theoclassical economics. The active use of fiscal policy to counter recessions was anathema, a tool of the Keynesian devil. The ECB’s theoclassical dogma was clear and proud: (1) democratic governments have perverse incentives to seek to lower unemployment, (2) which create an inflationary policy bias, which (3) can only be countered by a rigorously independent central bank, with (4) a mono-mission set by statute which rested exclusively on preventing inflation regardless of its short-term effect on unemployment, and (5) a belief that ending inflation would automatically minimize long-term unemployment.

In essence, the ECB declared that inflation causes recessions and that wage increases drive inflation. The ECB dogma on unemployment was internally inconsistent. The ECB (mostly) believed in a Phillip’s Curve – that reducing unemployment inevitably increased inflation and that a fanatic devotion to maintaining price stability maximized employment.

The problem, as a number of economists pointed out when the euro was being created, was that these ECB policies, together with the severe constraints (even in a recession) of the EU’s “growth and stability” pact, would inherently lead to a crisis when the EU faced a severe recession. Economic critics of the euro pointed out that the nasty scenario would be a recession that was far more severe in the periphery because ECB policies would be set by the German-French core with minimal policy input from the periphery. The core would demand austerity, which would lock the periphery, unable to devalue given their adoption of the euro and unable to adopt effective counter-cyclical fiscal policies due to the EU’s oxymoronic “growth and stability” pact, in a severe recession and expose the periphery to attacks on its debt. Nations that adopt the euro give up their fiscal and monetary sovereignty. The theory of the euro and the ECB was to let the people of the periphery twist slowly in the wind in the event of a serious recession.

The ECB was actually proud of this policy of indifference to the suffering of the periphery’s residents. The ECB reveled in its insistence on what might be called “tough love” for the never-to-be-trusted southern periphery. The inhumanity of the ECB’s mono-mission was intended. The unintended consequences of the ECB’s mono-mission, however, threatened the survival of the euro and the ECB. Indeed, the unintended consequences exposed the grave limits of the German and French devotion to creating an “ever closer European union.” The Great Recession revealed that the Germans and French did not really feel that they were part of a European nation dealing with fellow countrymen and women who were in need. No, they were being asked to bail out indolent Greeks, shiftless Irish, and easy-to-ignore Portuguese. The willingness of Germany’s leaders to bail out the periphery has almost nothing to do with EU solidarity and everything to do with bailing out German banks through a “below the radar” mechanism.

The ECB inherently must perform effectively four missions if the euro is to avoid causing repeated crises and, eventually, collapse. In addition to fighting severe inflation, the ECB must (1) minimize unemployment, (2) serve as a lender of last resort to member nations and banks, and (3) serve as a “regulatory cop on the beat” to prevent the epidemics of accounting control fraud in EU banks that hyper-inflated financial bubbles, rendered most of the EU’s largest banks insolvent, and caused the financial crises that shut down hundreds of financial markets and drove the Great Recession. The ECB, however, is not permitted to serve these other three missions under is mono-mission statute. It remains true however, that the prospect of being hung in a fortnight (or less) focuses central bankers’ minds most wondrously. The ECB has repeatedly risen above its theoclassical principles and the law governing its mission. Necessity has forced the ECB to adopt the lender of last resort function and (in economic substance regardless of the nominal structure) bail out banks and member nations.

The ECB remains indifferent, however, to the periphery’s unemployment. Indeed, the ECB’s demand for what our CIA refers to as “draconian” austerity programs (in Ireland), is the principal cause of increasing unemployment in much of the periphery. The ECB’s pro-cyclical policies are economically illiterate and will generate recurrent economic and political crises in the periphery that will soon bring to political power some of the most odious extremists in the EU. If the ECB continues its pro-cyclical policies it will produce a lost decade in the periphery and cause some nations to withdraw from the euro.

The ECB remains blind to the fact that it must ensure effective financial regulation, particularly of the systemically dangerous institutions (SDIs), if the euro and the ECB are to be effective. Accounting control frauds drove the crises in several European nations. Those crises imperiled the EU, the ECB, and the euro. The regulators must stop the “Gresham’s” dynamic that causes bad ethics to drive good ethics out of the financial markets. EU financial regulation suffered from what the authors of the book Guaranteed to Fail (Princeton 2011) call the “race to the bottom.” This perverse race towards anti-regulatory policies, another form of a Gresham’s dynamic, was decisive throughout the EU. Anti-regulators cannot break the Gresham’s dynamics that accounting control frauds create that lead to hyper-inflated financial bubbles and endemic fraud. Individual nation states cannot break the Gresham’s dynamic. They can divert the frauds to other nations by serving as the “regulatory cops on the beat,” but they cannot safeguard the EU. Only the ECB is in a position to provide that effective regulation and break the Gresham’s dynamic throughout the EU.

The ECB has, as predicted, risen above its principles and the mono-mission that the ECB championed. Its mono-mission imperiled the ECB’s ability to respond to the (not-so) sovereign debt crisis of the periphery and the European banks’ private and public debt crises. The ECB needs to rise above its principles and law to reduce the severe unemployment and economic suffering caused by the current crisis and become an effective regulatory “cop on the beat” to prevent or at least sharply limit future crises.

The High Price of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors’ Failure to Read Akerlof & Romer

(Cross-posted from Benzinga.com)

By reviewing the annual reports (2005-2007) of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) I learned that the Council had some interest in fraud, but no understanding of elite fraud and its implications for the economy. The reports make sad reading. They deny the developing crisis entirely and they do so for reasons that reflect badly on economics and economists.

The CEA’s reports’ analysis of the developing fraud epidemics and crisis reveal critical weaknesses in theory, methodology, empiricism, candor, objectivity, and multi-disciplinarity. Overwhelmingly, the reports ignored the developing crises and their causes. Worse, as late as 2007, they denied – even after the bubble had popped – that there was a housing bubble. When the nation and the President vitally needed a warning from its Council of Economic Advisors the CEA did not simply fail to warn, but actually advised that those who warned of a coming crisis were wrong.

This column does not focus on the CEA’s claims that there was no housing bubble. Like the National Association of Realtors’ top economist who became known to the trade press as “Baghdad Bob” (the mocking nickname journalists gave Saddam Hussein’s press flack after he denied U.S. troops were in Baghdad), the CEA’s specious bubble denial is an obvious embarrassment. Their Japanese counterparts did far better in warning of the developing real estate bubble in the 1980s. The collapse of the twin Japanese bubbles in 1990 and the resultant “lost decade” should have caused the CEA to recognize the gravity of the risk bubbles pose and importance of identifying them promptly. Instead, the CEA gave in to the temptation to claim that the President’s brilliant policies had produced a wonderful economy. The reality was that the economy was headed over the precipice.

The focus of this column is on the portion of the CEA’s annual report for 2006 that discussed the theory of financial intermediation and financial regulation. Indeed, the column focuses on a small subset of the defects in those portions of the report. I write to emphasize how a theory (“control fraud”) developed two decades ago by regulators, criminologists, and economists could have saved the CEA from analytical and policy errors with regard to financial crises and regulation and led it to identify the crisis and recommend effective measures to contain it. The tragedy is that the CEA discussion of the theory of financial regulation embraces three of the most useful theoretical insights – adverse selection, lemon’s markets, and the centrality and criticality of sound underwriting to the survival of lending institutions. These theories are interrelated and they are essential components of control fraud theory.

Had the CEA understood the true import of these three economic theories it could have gotten the crisis right instead of making things worse. White-collar criminologists and economists share these three theories (among others) and employ a (limited) “rational actor” model. (Criminologists never made the mistake of assuming purely rational behavior. Even neoclassical economists now generally acknowledge that behavioral economics research demonstrates that economic behavior can be irrational in important settings.) In the 1980s and early 1990s, the efforts of a small group of criminologists, economists, and regulators to understand the causes of the developing S&L debacle led them to develop a synthetic theory that criminologists refer to as “control fraud theory.” Unfortunately, the typical theoclassical economic treatment of these three theories, exemplified by the CEA’s 2006 report, ignores control fraud. The result is that the 2006 CEA report misstated the predictions of each of the three theories that it discussed and concluded “no problem here.” In reality, the three theories predicted that there were epidemics of accounting control fraud

that were leading inevitably to a catastrophic crisis.

The context of the 2006 CEA report’s discussion of the three theories is a treatise on the theory of financial intermediation and its implications for financial regulation. The treatise is over the top in its praise of the U.S. financial industry. The CEA claimed that the U.S. financial deregulation gave its financial sector a “comparative advantage” over other nations. The CEA cited the financial sector’s rapid growth in size and profits as proof of this comparative advantage and asserted that the financial sector’s rapid growth led to more rapid U.S. economic growth and increased financial stability. The CEA’s theory of financial intermediation posited that banks exist to minimize the informational difficulties that beset lending and investment. The CEA concluded that U.S. banks were growing rapidly because deregulation made them ever more efficient in minimizing these informational defects.

Adverse Selection

The CEA addressed three forms of informational defects that banks helped reduce. The CEA began by discussing “adverse selection.” Adverse selection was the key to understanding and preventing the developing crisis. In the lending context, adverse selection arises when a lender’s policies selectively encourage lending to borrowers who pose greater credit risks that are unknown or underestimated by the lender. Adverse selection can be one of the consequences of “asymmetrical information.” (Adverse selection also poses a serious risk to honest insurance companies.)

Because the lender does not know (and therefore is not compensated for) the full extent of the risk of default adverse selection produces a “negative expected value” for lenders. In plain English, they lose money. For a residential mortgage lender, adverse selection is fatal because the loans are so large and the loan proceeds are fully disbursed at closing. It is essential to understand that adverse selection is not equivalent to credit risk. A mortgage lender makes money by taking prudent credit risks. Banks “underwrite” prospective borrowers and collateral in order to identify, understand, quantify, and price credit risk. Prudent underwriting minimizes adverse selection. Mortgage lenders that fail to underwrite create severe adverse selection and fail. Honest home lenders would never gut their underwriting standards and create adverse selection.

The existence of a secondary market does not change an honest home lender’s incentive to engage in prudent underwriting. Neoclassical theory predicts that the ultra sophisticated investment banks that ran the secondary market would only purchase loans they had prudently underwritten. A lender that failed to underwrite effectively would be unable to sell its loans in the secondary market. Neoclassical theory also predicts that the secondary market would only purchase loans sold with guarantees against fraud. The first prediction, of course, proved false but the second prediction was typically true. All of the mortgage lenders that specialized in making large numbers of loans under conditions that maximized adverse selection failed even before the cost of the guarantees would have destroyed them because their “pipeline” losses exceeded their trivial (fictional) capital.

The most severe form of adverse selection is fraud. The ultimate form of adverse selection is accounting control fraud. Any experienced banker or insurer knows that adverse selection can lead to fraud. Fraud maximizes the asymmetry of information because the information provided to the victim contains data that are false and material. The fraud makes the loan look far less risky than it really is.

In 2006, MARI, the anti-fraud group of the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), reported to MBA members that “stated income” loans were an “open invitation to fraudsters” and that they deserved the term used behind closed doors in the industry, “liar’s loans,” because the incidence of fraud in liar’s loans was 90 percent. The defining element of liar’s loans was the failure to conduct essential underwriting. Moreover, fraudulent nonprime lenders typically simultaneously maximized adverse selection and created deniability by creating large networks of loan brokers to prepare the fraudulent loan applications.

The percentage of nonprime loans made without prudent underwriting is not known with precision because there were no official definitions of stated income, alt-a, or liar’s loans. Subprime and liar’s loans were not mutually exclusive. By the time the CEA wrote its 2006 report roughly half of the loans lenders termed “subprime” were also liar’s loans. Credit Suisse’s March 12, 2007 study (“Mortgage Liquidity du Jour: Underestimated No More”) presented data estimates that roughly 30% of all mortgage loans made in 2006 were liar’s loans. That frequency produces an annual mortgage fraud incidence of well over one million. The FBI had put the entire nation on alert about the developing “epidemic” of mortgage fraud in its September 2004 House testimony. The FBI predicted that the fraud epidemic would cause a financial “crisis” unless the epidemic was contained. In 2006, no one believed that the epidemic was being contained.

What everyone, including the CEA, knew in 2006 was that mortgage underwriting standards for nonprime loans were in freefall while other “layered risk” characteristics were multiplying. This meant that nonprime lenders were dramatically increasing adverse selection while making loans that were ever more vulnerable to losses from adverse selection. Everyone, including the CEA, knew that the only reason this could occur was the rapid growth of the three “de’s” – deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization. Everyone, including the CEA, knew that no one was forcing the nonprime lenders to make liar’s loans. That should have led the CEA to ask why the senior officers controlling nonprime lenders were deliberately causing the lenders to make loans that created intense adverse selection, endemic fraud, massive (longer-term) losses, and the failure of the lender. That behavior makes no sense under the theory of financial intermediation advanced by the CEA. No honest lender CEO would engage in that pattern of behavior. The nonprime lender CEOs’ behavior only makes sense if they are engaged in accounting control fraud. The recipe for maximizing fictional accounting income has four ingredients and adverse selection optimizes the first two (rapid growth through making very poor quality loans at premium yields).

Unfortunately, the CEA’s 2006 report was devoid of any real analytics or facts related to adverse selection. Indeed, the report’s entire discussion of financial institutions is bizarre because it is not simply removed from any factual context but based on factual assumptions that were contrary to reality and becoming ever more contrary to reality in 2006. The discussion is a surreal theoretical exercise based on unstated factual assumptions that are the opposite of reality. The (inevitable) result of its unstated assumptions is the worst possible financial regulatory policy advice that the CEA could give in 2006 – everything is wonderful because our financial intermediaries prevent adverse selection. The CEA wrote to warn us of the dangers of excessive financial regulation at a time when financial regulation had been eviscerated.

The CEA’s discussion of adverse selection ignored the risk of fraud during what the FBI had aptly termed a fraud “epidemic.” Instead, it premised its concern on managers of high quality projects being unwilling to seek commercial loans from banks because banks charged excessive interest rates for even high quality projects because of their inability to differentiate bad and high quality business projects. In reality, interest rates on commercial loans were exceptionally low – even for poor quality business projects. The CEA’s discussion of adverse selection was premised on an alternate universe.

Lemon Markets

The CEA discussed lemon markets in conjunction with its discussion of adverse selection. A lemon market reaches its nadir when bad quality products drive good quality products out of the marketplace. Control fraud theory agrees that lemon market and adverse selection are interrelated theories and provide the keys to understanding why control frauds cause such devastating injury. George Akerlof was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001 for his 1970 article on markets for lemons, which was a pioneering article on fraud and asymmetrical information. As I have explained, fraud produces the epitome of adverse selection and control fraud is the ultimate form of fraud. The examples Akerlof provided of sales of goods that posed lemon problems were anti-customer control frauds.

The CEA does not mention Akerlof in its discussion of lemon markets. This was deeply unfortunate, for it reinforced the CEA’s failure to discuss the epidemic of control fraud by nonprime lenders. The CEA also failed to explain one of Akerlof’s most important theoretical contributions in his 1970 article, the “Gresham’s” dynamic. Akerlof used Gresham’s law (bad money drives good money out of circulation in hyperinflation) as a metaphor to explain why market forces became perverse in the presence of asymmetrical information. The anti-customer control fraud that sells an inferior good through the claim that it is a high quality good gains a large cost advantage over its honest competitors. If they are driven into bankruptcy or emulate the fraudulent practices good quality goods – and honest sellers – will be driven from the marketplaces by competition. This happened recently in the Chinese infant formula market, where honest manufacturers were driven out of the market, six infants were killed, and over 300,000 were hospitalized. The perverse effects of extreme executive compensation largely driven by short-term reported earnings have now created a perverse Gresham’s dynamic in many firms, particularly in the finance industry. The CEA did not mention the perverse incentives produced by control fraud and modern executive compensation and why markets make the environment even more criminogenic rather than restraining fraud. Implicitly, however, the CEA recognized that there was some perverse market dynamic that could drive lemon markets to their nadir where “only the worst-quality” good would be sold.

The CEA compounded its error of not discussing Akerlof’s 1970 analysis of control fraud and the Gresham’s dynamic by failing to address George Akerlof and Paul Romer’s 1993 article (“Looting: the Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit”). Their 1993 article analyzed accounting control frauds. The CEA’s discussion of financial intermediaries also included a discussion of “moral hazard.” As with its discussion of adverse selection, the CEA’s discussion of moral hazard implicitly excluded all fraud. There is no theoretical basis for this exclusion. Economics (and reality) has long recognized that moral hazard can lead to excessive risk or fraud. Fraud is often a superior strategy (in terms of expected value – not morality). As Akerlof & Romer stressed, accounting control fraud is a “sure thing” (1993: 5). “Gambling for resurrection” is a near sure thing, but in the opposite direction. The economic theory of how the insolvent or failing bank’s owners maximize the value of their “option” predicts that they will engage in such extraordinary risk that their gamble will nearly always fail.

But Akerlof & Romer endorsed another point that S&L regulators and criminologists stressed – the manner in which S&Ls purportedly engaged in honest gambling due to moral hazard made no sense for a rational (honest) actor. Please read their explanation with particular care for its obvious application to our ongoing crisis should be glaring.

“The problem with [economists’ conventional description of moral hazard as an] explanation for events of the 1980s is that someone who is gambling that his thrift might actually make a profit would never operate the way many thrifts did, with total disregard for even the most basic principles of lending: maintaining reasonable documentation about loans, protecting against external fraud and abuse, verifying information on loan applications, even bothering to have borrowers fill out loan applications.* Examinations of the operation of many such thrifts show that the owners acted as if future losses were somebody else’s problem. They were right (1993: 4).”

Akerlof & Romer went on to explain that accounting control frauds optimize fictional income by making loans with a negative expected value and by deliberately seeking out borrowers with poor reputations (1993: 17). Their logic relies implicitly on the deliberate creation of adverse selection by the lender and the creation of a Gresham’s dynamic both among borrowers and those that aid and abet the CEO’s frauds, e.g., the appraisers when they inflate appraisals.

There is no good explanation for why the CEA would cite the Akerlof’s famous theory on lemon markets yet ignore the FBI’s 2004 warning, the experience of the S&L debacle (and the public administration literature on the successful regulatory fight against the control frauds), the Enron era accounting control frauds, Akerlof & Romer’s theory of accounting control fraud, and criminology’s theory of control fraud. The basic fraud mechanisms had so many parallels that one is forced to the conclusion that the CEA and its staff never read the most important modern economic article on bank failures. Akerlof & Romer explicitly noted that accounting fraud created perverse “lemon” projects (1993: 29). It is bizarre that the CEA wrote in 2006 for the express purpose of opposing essential financial regulation and thought that the best way to make its case was to cite theories most closely associated with George Akerlof while ignoring his application of those theories to financial regulation and his research findings on the reality of accounting control fraud. Note that Akerlof & Romer were writing about precisely the point the CEA was discussing – the role of banks with respect to information asymmetries. Worse, Akerlof & Romer’s point was that one could not assume that banks acted to reduce information asymmetries because banks engaged in accounting control fraud did the opposite. Akerlof & Romer also explained how accounting control frauds caused Texas real estate bubbles to hyper-inflate. If there was one economics article the CEA needed to read carefully it was Akerlof & Romer. Akerlof was a Nobel Prize winner well before the CEA wrote its 2006 annual report.

But the CEA could have learned the same vital facts about fraud and financial crises had it read the criminology literature, the regulatory literature on the S&L debacle, or the public administration literature. The CEA had experienced recently the Enron-era accounting control frauds and the S&L debacle was relatively recent. The CEA’s failure to even consider the role of fraud in financial crises, particularly after the FBI’s stark warning in 2004, was unconscionable. Akerlof & Romer went out of their way to warn economists of the dangers of control fraud.

“Neither the public nor economists foresaw that the [S&L] regulations of the 1980s were bound to produce looting. Nor, unaware of the concept, could they have known how serious it would be. Thus the regulators in the field who understood what was happening from the beginning found lukewarm support, at best, for their cause. Now we know better. If we learn from experience, history need not repeat itself (1993: 60).”

My criminology colleagues and I sent the same warnings, as did the S&L regulators and public administration scholars. The FBI sent an explicit warning. None of us were able to get through to the Clinton, Bush, or Obama administrations. They have all ignored the epidemic of accounting control fraud that hyper-inflated the real estate bubbles and drove the financial crisis.

The Necessity and Centrality of Effective Underwriting

The CEA report continues its triumphal “just so” story approach to financial services by explaining how banks develop expertise in evaluating credit risk and use collateral as a means of inducing borrowers to “truthfully” rather than “strategically” release information on the true value of the real estate to the lender. By 2006, the nonprime industry was notorious for deliberately inflating appraisal values so that it could make more and larger fraudulent loans. Surveys of appraisers showed widespread efforts by lenders and their agents to coerce appraisers to inflate valuations. No honest lender would ever coerce an appraiser to inflate a collateral valuation. Only lenders and their agents can engage in widespread appraisal fraud. Appraisal fraud is a “marker” of accounting control fraud. The “strategic” behavior with regard to appraisers was by fraudulent lenders and their agents. It relied on endemic, deliberate deceit. Appraisal fraud is particularly egregious in residential home lending because it can lead borrowers to overpay for their home and to fail to understand the risks of purchasing a home.

The greatest analytical defect in this section of the CEA report, however, is its false dichotomy between economic efficiency and financial regulation. The CEA was on to something important. A well run banking system does reduce adverse selection and make markets less inefficient. A well run banking system does so by engaging in expert underwriting of significant loans such as home loans. A bank that does not engage in expert underwriting poses a grave danger. At best, it is incompetent. Far more dangerously, it is often engaged in accounting control fraud. A regulation that requires a lender to engage in prudent underwriting imposes no costs on honest banks and it saves society from vast amounts of damage. When the regulatory agencies gutted the underwriting rules by turning them into guidelines they set us on the road to the Great Recession. Effective financial regulation begins with mandating prudent underwriting. Rules mandating prudent underwriting make financial markets far more efficient and stable by blocking the perverse Gresham’s dynamic that otherwise can create a criminogenic environment.

The CEA was correct in explaining that the raison d’être of financial intermediaries is the provision of exemplary underwriting. It is, of course, significantly insane that the CEA would implicitly assume in 2006, contrary to known facts, that nonprime lenders, the investment banks packaging CDOs, and the rating agencies were prospering because they were engaged in exemplary underwriting. The CEA, in the two most important reports it issued in modern times (2005 and 2006), got the developing financial crisis and regulatory policy as wrong as it is possible to get something wrong.

Conclusion

No economist should be allowed to graduate from a doctoral program without reading Akerlof & Romer. It would also be salutary to expose any doctoral candidate interested in finance or regulation to the relevant work of criminologists and public administration scholars. Collectively, our work on control fraud has shown great predictive strength while neoclassical economic work (both macro and micro) and “modern finance” have suffered repeated, abject predictive failures.

Every financial regulatory agency should have a “chief criminologist.” The financial regulatory agencies are civil law enforcement entities whose primary responsibility is to limit control fraud, but they virtually never have anyone in authority with expertise in identifying, investigating, and sanctioning control frauds.

* Black (1993b) forcefully makes this point.

Council of Economic Advisors’ Annual Reports 2005-2007: No Crisis Here

By William K. Black

* Cross-posted from Benziga

* Cross-posted from Benziga

I decided to look at what President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) were saying in their annual reports for 2005-2007 about the massive real estate bubble, epidemic of accounting control fraud and mortgage fraud, the resultant rapidly developing financial crisis, and the great increase in economic inequality. Here’s what I found on these topics.

CEA Annual Report for 2005

N. Gregory Mankiw chaired the CEA.

Home ownership reached a record 69%. Home prices were surging. No discussion of the developing bubble. The CEA was enthused by the housing sector.

No mention of subprime or nonprime loans (or any variants, e.g., stated income).

There was no discussion of financial institutions’ risk.

There was no mention of Fannie or Freddie.

No mention of the FBI’s September 2004 warning that there was an “epidemic” of mortgage fraud or the FBI’s prediction that the fraud would cause a financial “crisis” if it were not stopped. No mention of mortgage fraud.

The report contained an extensive discussion of Internet frauds.

No use of the term “inequality,” but discussion of some of the factors increasing inequality. It does not discuss the perverse incentives arising from executive compensation tied to short-term reported firm income.

CEA Annual Report for 2006

No CEA chair listed because no replacement was in place after Bernanke’s resignation when he was appointed as the Fed’s Chair.

“During the past five years, home prices have risen at an annual rate of 9.2 percent.” The report argues that this was driven by increased demand and lower financing costs. It does not use the word “bubble,” but it argues that there is no bubble.

No mention of subprime or nonprime loans (or variants).

Chapter 9 of the report is devoted to financial institutions. The CEA argues that the U.S. has a “comparative advantage” in financial services. It premises its analysis of financial institutions on information asymmetries. It has a glaring false tone at the start of this discussion when it asks: “why do [banks] ask for so much information before making a loan….? By early 2006, of course, the striking change was how little information banks verified. The CEA explains the concepts of adverse selection, moral hazard. The explanation is critically flawed in that it ignores fraud despite the fact that adverse selection and moral hazard are exceptionally criminogenic. Again, the CEA ignores the FBI’s warnings of the growing mortgage fraud epidemic and ignores the risk of accounting control fraud by financial institutions and their agents. It notes that banks can take steps that are known to minimize adverse selection and moral hazard, but ignores the vital fact that the officers that controlled the nonprime lenders typically refused to take such steps (even though any honest businessman would do so) and that nonprime lending was vast and growing rapidly.

The CEA’s discussion of these topics is bizarre – it fails to recognize or address the implications of the fact that nonprime lenders are acting in a manner directly contrary to the economy theory the CEA argues explains why financial intermediaries exist. Under the CEA’s theories, the actions of the nonprime lenders are rational only for accounting control frauds. In conjunction with the FBI’s 2004 warnings that the growing fraud epidemic would cause a financial crisis this should have caused the CEA to issue a stark warning. Instead, the discussion is triumphal. The CEA even sees the tremendous increase in GDP devoted to the financial sector as desirable – proof that the U.S. has a “comparative advantage” in finance over the rest of the world. The CEA then claims that this advantage leads to exceptional U.S. growth and stability, helping to produce the “Great Moderation.” Deregulation and the rise of financial derivatives explain our comparative advantage in finance, the Great Moderation, and our superior economic growth. This self-congratulatory dementia achieves self-parody when the CEA lauds “cash-out-mortgage refinancing” for purportedly having “moderate[d] economic fluctuations.” The CEA’s discussion of “safety and soundness” regulation is overwhelmingly a highly generalized description of Basel I and II.

Chapter 9 discusses the need to combat identity fraud as one of its prime (and rare) examples of desirable forms of consumer protection, but it primarily emphasizes the dangers of consumer protection regulation and attacks the (repealed) Glass-Steagall Act.

Chapter 9 discusses Fannie and Freddie and their systemic risk. More precisely, it assumes that the systemic risk arises from prepayment risk – not credit risk. Accordingly, it explains that the administration wants Fannie and Freddie to expand their securitization of lower credit quality home loans (“for a wider range of mortgages”) while decreasing the number of home loans Fannie and Freddie hold in portfolio so that they can reduce their prepayment risk.

The report uses the term “inequality” and ascribes the growing inequality overwhelmingly to the distribution of skills. It does not discuss the perverse incentives arising from executive compensation tied to short-term reported firm income.

CEA Annual Report for 2007

Edward P. Lazear, CEA Chair.

The report does not mention the word “bubble” and continues to argue that the price increases in housing are due to rising demand for housing and lower financing costs. The CEA claims that the growth in home prices during the decade was “modest” in most metropolitan areas. The growth in most metropolitan areas was materially faster than GDP and population growth. The report admits that all housing indices fell sharply in 2006, but stresses that unemployment is falling and claims that the fall in housing may increase growth in other sectors by reducing “crowding out” effects in private investment.

The report does not mention mortgage fraud or accounting control fraud by lenders and their agents. It mentions fraud in two contexts. First, it states that it is possible that regulation could reduce fraud with respect to disaster insurance. Second, it notes that fraudulent papers can make it difficult for employers to avoid hiring undocumented immigrants.

No mention of subprime or nonprime loans (or variants).

The report does not mention Fannie or Freddie.

The report uses the term “inequality” and ascribes the growing inequality overwhelmingly to the distribution of skills. It does not discuss the perverse incentives arising from executive compensation tied to short-term reported firm income.

Conclusion

During the key period 2005-2007 when the epidemic of mortgage fraud driven by the accounting control frauds hyper-inflated the bubble and set the stage for the Great Recession the President’s Council of Economic Advisors were oblivious to the developing fraud epidemics, bubble, and the grave financial crisis they made inevitable absent urgent intervention by the regulators and prosecutors. President Bush’s economists in this era were blind to the factors that were making the financial environment so criminogenic (e.g., deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization plus grotesquely perverse executive and professional compensation). They typically did not make any relevant policy advice and when they did it was the worst possible advice warning of the grave dangers of regulations designed to reduce adverse selection. They were so blind that they did not even find it worthy of reporting that there were over a million “liar’s” loans being made annually.

The only CEA report that even attempted to address financial regulation discussed a theoclassical fantasy world that bore increasingly little relationship to the reality of nonprime mortgage lending. The tragedy is that “adverse selection” and lemon’s markets are superb building blocks for analyzing the frauds that drove the crisis and for understanding why only liars make a business out of making liar’s loans in the mortgage context. The CEA did not warn of any credit risk at Fannie and Freddie. Indeed, it urged them to make more loans to weaker credit risks as long as they securitized the loans. Securitization would not have reduced Fannie and Freddie’s credit risk.

William Black Interviewed on Benzinga Radio

William K. Black was interviewed recently regarding Bank of America’s proposed settlement announced last week. Listen to the audio here.

Comments Off on William Black Interviewed on Benzinga Radio

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged William K. Black

Dawn of the Gargoyles: Romney Proves He’s Learned Nothing from the Crisis

By William K. Black

Mitt Romney chose to unveil the economic plank of his campaign for the Republican nomination with a speech in Aurora, Colorado decrying banking regulation. He could not have picked a more symbolic location to make this argument, for Aurora is the home and name of one of the massive financial frauds that caused the Great Recession. Lehman Brothers’ collapse made the crisis acute and Lehman’s subsidiary, Aurora, doomed Lehman Brothers. Lehman acquired Aurora to be its liar’s loan specialist. The senior officers that Lehman put in charge of Aurora, which was inherently in the business of buying and selling fraudulent loans, set its ethical plane at subterranean levels.

Aurora sealed Lehman’s fate by serving as a “vector” that spread an epidemic of mortgage fraud throughout the financial system and caused catastrophic losses far greater than Lehman’s entire purported capital. Aurora epitomizes what happens when we demonize the regulators and create regulatory “black holes.” Romney literally demonized banking regulators as “gargoyles” and claimed that banking regulations and regulators were the cause of the economy’s weak recovery.

On April 20, 2010, I testified before the Committee on Financial Services of the United States House of Representatives regarding Lehman’s failure. I was the witness chosen by the (then) Republican minority because they wished to have testimony from an experienced and successful financial regulator who would pull no punches in critiquing the failures of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve (the Fed), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with regard to Lehman. The Republicans’ target was the former President of the FRBNY, Timothy Geithner.

My House testimony explained why Aurora was the key to understanding Lehman’s failure and the causes of the financial crisis.

Lehman was a “control fraud.” That is a criminology term that refers to situation in which the persons controlling a seemingly legitimate entity use it as a “weapon” (Wheeler & Rothman 1982) of fraud (Black 2005). Financial control frauds’ “weapon of choice” for looting is accounting.

Lehman’s nominal corporate governance structure was a sham. Lehman was deliberately out of control with regard to “risk” in its dominant operation – making “liar’s loans.” Lehman did not “manage” the risk of making liar’s loans. It engaged in massive, fraudulent transactions that were “sure things” (Akerlof & Romer 1993). The Valukas Report … provides further evidence of the accuracy of George Akerlof and Paul Romer’s famous article – “Looting: Bankruptcy for Profit.” The “looting” that Akerlof & Romer identified is a “sure thing” in both directions – firms that loot through accounting scams will report superb (fictional) income in the short-term and catastrophic losses in the long-term.

The value of Lehman’s Alt-A mortgage holdings fell 60 percent during the past six months to $5.9 billion, the firm reported last week.[1]

This roughly $9 billion loss, in 2008, was an important factor in destroying Lehman, but it represents only losses on liar’s loans still held in portfolio. Aurora specialized in making liar’s loans and Aurora’s loans caused massive losses because they were pervasively fraudulent. Lehman sold tens of billions of dollars of liar’s loans through Aurora and a subsidiary (BNC Mortgage) that specialized in making subprime loans – roughly half of which were liar’s loans by 2006. The purchasers of these fraudulent loans had the legal right and economic incentive to require Lehman to repurchase the loans, which would have far exceeded Lehman’s reported capital. Making and selling fraudulent liar’s loans doomed Lehman. Lehman was one of the largest vectors that spread fraudulent mortgage paper throughout much of Europe and the United States.

Lehman had become the only vertically integrated player in the industry, doing everything from making loans to securitizing them for sale to investors.

***

Lehman was a dominant player on all sides of the business. Through its subsidiaries – Aurora, BNC Mortgage LLC and Finance America – it was one of the 10 largest mortgage lenders in the U.S. The subsidiaries fed nearly all their loans to Lehman, making it one of the largest issuers of mortgage-backed securities. In 2007, Lehman securitized more than $100-billion worth of residential mortgages.

These demands posed a much larger problem: contagion. Because these CDOs were thinly traded, many of them did not yet reflect the loss in value implied by their crumbling mortgage holdings. If Bear Stearns or its lenders began auctioning these CDOs off, and nobody wanted to buy them, prices would plummet, requiring all banks with mortgage exposure to begin adjusting their books with massive writedowns.

Lehman, despite its huge mortgage exposure, appeared less scathed than some. Mr. Fuld was awarded $35-million in total compensation at the end of the year.

The volume of liar’s loans and subprime loans was everything – as long as Lehman could sell the liar’s loans to other parties. Volume created immense real losses, but it also maximized Dick Fuld’s compensation. Nonprime loans drove Lehman’s (fictional) gains in income and capital under Fuld.

Lehman’s real estate businesses helped sales in the capital markets unit jump 56 percent from 2004 to 2006, faster than from investment banking or asset management, the company said in a filing. Lehman reported record earnings in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

As MARI, the mortgage lending industry’s own anti-fraud experts, warned the industry in 2006, making liar’s loans is an “open invitation to fraudsters.” Even Lehman’s internal studies found, by reviewing only the loan files, exceptional levels of fraud.

Mark Golan was getting frustrated as he met with a group of auditors from Lehman Brothers.

It was spring, 2006, and Mr. Golan was a manager at Colorado-based Aurora Loan Service LLC, which specialized in “Alt A” loans, considered a step above subprime lending. Aurora had become one of the largest players in that market, originating $25-billion worth of loans in 2006. It was also the biggest supplier of loans to Lehman for securitization.

Lehman had acquired a stake in Aurora in 1998 and had taken control in 2003. By May, 2006, some people inside Lehman were becoming worried about Aurora’s lending practices. The mortgage industry was facing scrutiny about billions of dollars worth of Alt-A mortgages, also known as “liar loans”– because they were given to people with little or no documentation. In some cases, borrowers demonstrated nothing more than “pride of ownership” to get a mortgage.

That spring, according to court filings, a group of internal Lehman auditors analyzed some Aurora loans and discovered that up to half contained material misrepresentations. But the mortgage market was growing too fast and Lehman’s appetite for loans was insatiable. Mr. Golan stormed out of the meeting, allegedly yelling at the lead auditor: “Your people find too much fraud.”

After the FBI warned in September 2004, that there was an “epidemic” of mortgage fraud, after Lehman’s internal auditors found endemic fraud in their liar’s loans, after MARI warned the industry in 2006 that studies of liar’s loans found a fraud incidence of 90%, after the bubble had stalled in 2006, and after scores of mortgage banks that specialized in making nonprime loans failed – Lehman significantly increased the rate at which Aurora made liar’s loans. In 2006, Aurora originated roughly $2 billion a month.

BNC was Lehman’s subsidiary that specialized in subprime loans. By 2006, roughly half of its loans were liar’s loans to borrowers with poor credit records.

Lehman’s pattern of conduct seems bizarre because no honest firm would make liar’s loans. The pattern, however, is optimal for an accounting control fraud. The people who control fraudulent lenders optimize their compensation by maximizing the bank’s short-term reported income. The “recipe” for maximizing fictional income (and real losses) has four ingredients:

- Extremely rapid growth by

- Making poor quality loans at a premium yield while employing

- High leverage and

- Providing only grossly inadequate allowances for loan and lease losses (ALLL)

The officers controlling a fraudulent lender find it necessary to eviscerate the bank’s underwriting in order to be able to make large amounts of bad loans. The managers deliberately create a fraud-friendly culture, and Aurora demonstrated how extreme the embrace of fraud could become.

The HR lady pulled Michael Walker into a room and told him he was fired.

The reason: Talking to the FBI. It was a violation of the company’s privacy policy.

“I was stunned,” Walker told me. “I couldn’t believe it. But that’s what she said.”

Walker, a “high-risk specialist,” was then walked out of the building as if he were the risk. His job at Aurora Loan Services LLC, Littleton, Colo., ended on Sept. 4, 2008.

His job was to uncover mortgage fraud. But he claims he was fired for doing it. In a lawsuit recently filed in Denver District Court, he claims Lehman’s mortgage subsidiary wanted to remain profitably unaware of fraud.

Aurora [personnel] got paid by loan volume, not by loan quality.

Consequently, Walker and his fraud-seeking colleagues were always busy.

“They just absolutely flooded us with work,” he said. “There was no way we could possibly keep up with it. And that’s what they wanted.

“They were putting the loans into an investment trust,” he explained. “When they became aware of fraud, they had to buy those loans back out of the trust. So it ended up costing them money.”

But Walker couldn’t play this game. A “Suspicious Activity Report” that he filed in 2006 led to interviews with the FBI and the IRS in 2008, and then ultimately to his bizarre dismissal.[2]

Lehman’s senior managers consciously chose to take the unethical path because they knew it generate extraordinary reported income in the short-term, which would maximize their compensation. Prior to becoming one of the world’s largest purchasers and sellers of nonprime loans through Aurora and BNC, Lehman had eagerly embraced fraudulent and predatory lending. The officers who controlled Lehman also showed in this earlier episode that they would choose that short-term reported income that maximized their compensation even when they were warned that it was produced by fraud and abuse of the customers and knew that the loans would produce large losses,

Mr. Hibbert was a vice-president at Lehman Brothers and he’d been sent to meet First Alliance founder Brian Chisick to see if Lehman could form some kind of relationship with the mortgage lender.

[Hibbert] pointed out that “there is something really unethical about the type of business in which [First Alliance] is engaged.”

Mr. Chisick had become one of the biggest players in subprime loans. First Alliance’s annual revenue had doubled in four years to nearly $60-million (U.S.) and its profit had increased threefold to $30-million.

“It is a sweat shop,” [Hibbert] wrote. “High pressure sales for people who are in a weak state.” First Alliance is “the used car salesperson of [subprime] lending. It is a requirement to leave your ethics at the door. … So far there has been little official intervention into this market sector, but if one firm was to be singled out for governmental action, this may be it.”

Despite the warning, Lehman officials recommended a $100-million loan facility for First Alliance. Mr. Chisick turned it down, but he agreed to take a $25-million line of credit and hire Lehman to work with Prudential on several securitizations.

At this juncture, Hibbert’s warnings of a governmental response proved accurate. Various state Attorneys General began to sue First Alliance for consumer fraud. Prudential terminated its ties with the lender.

But Lehman jumped at the opportunity to move in. Senior vice-president Frank Gihool asked Mr. Hibbert to pull together a review of First Alliance for Lehman’s credit risk management team. Mr. Hibbert once again marvelled at the company’s operations and financial outlook. But he also said the lawsuits posed a serious problem. The allegation about deceptive practices “is now more than a legal one, it has become political, with public relations headaches to come,” he wrote.

Nonetheless, on Feb. 11, 1999, Lehman approved a $150-million line of credit, and became the company’s sole manager of asset-backed securities offerings. The bottom line for Lehman was made clear in another internal report: The firm expected to earn at least $4.5-million in fees.

But within a year, the weight of the lawsuits crippled First Alliance. On March 23, 2000, the company filed for bankruptcy protection. Mr. Chisick managed to walk away with more than $100-million in total compensation and stock sales over four years. Lehman, owed $77-million, collected the full amount, plus interest.

First Alliance eventually settled the lawsuits filed by the state attorneys, agreeing to pay $60-million. In the California class-action case, a jury found Lehman partially responsible for First Alliance’s conduct and ordered the firm to pay roughly $5-million.

Romney is Echoing the Anti-regulatory Dogma that Caused the Crisis

Aurora and BNC Mortgage were regulatory “black holes.” The Fed had unique authority under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA) to regulate all mortgage lenders and had unprecedented practical leverage during the crisis because of its ability to lend to investment banks and convert them to commercial bank holding companies. Fed Chairmen Greenspan and Bernanke, despite pleas from Dr. Gramlich, refused to use this authority to close the regulatory black hole. Bernanke finally, under repeated pressure from Congressional Democrats, used the Fed’s HOEPA authority in August 2008 – over a year too late to even minimize losses. Greenspan and Bernanke were chosen to lead the Fed because of their intense, anti-regulatory dogma. Greenspan was notorious for his assertion that fraud provided no basis for regulation. He believed that financial markets automatically excluded fraud.

The SEC was equally notorious for its anti-regulatory policies. It created the disgraceful non-regulation regulation of Lehman and its four sister investment banks. The Consolidated Supervised Entities (CSE) program never made the SEC a real “primary regulator.” The SEC is incapable, as constituted, staffed, and led to be a primary regulator of anything – and that includes the rating agencies. “Safety and soundness” regulation is a completely different concept than a “disclosure” regime. The SEC’s expertise, which it has allowed to rust away for a decade, is in enforcing disclosure requirements. The SEC did not have the mindset, rules, or appropriate personnel to make the CSE program a success even if the agency had been a “junk yard dog.” Given the fact that the SEC was self-neutered by its leadership during the period Lehman was in crisis in 2001-2008, there was no chance that it would succeed even if the CSE been a real program.

The reality is that the CSE was a sham. The EU announced that it would begin regulating foreign investment banks doing business in the EU unless they were subject to consolidated supervision by their domestic regulator. The U.S., however, had no consolidated supervision of investment banks. The five largest U.S. investment banks were scared of the prospect of EU regulation. Their solution was for the SEC to create a faux regulatory system. The SEC assigned three staffers to be primarily responsible for each of the five, massive investment banks. In order to examine and supervise an entity of their size and complexity, a realistic staff level would begin at 150 regulators per investment bank.

The SEC’s only hope with respect to Lehman was to form an effective partnership with the Fed. An SEC/Fed partnership would at least have some chance. The Valukas report reveals that the FRBNY staff at Lehman recognized that the SEC’s staff at Lehman’s offices was not capable of understanding its financial condition.

Why we suffered the Great Recession and such a slow recovery

The primary cause of severe bank failures has long been senior insider fraud (James Pierce, The Future of Banking (2001). We know the characteristics that cause the criminogenic environments that produce the epidemics of accounting control fraud that cause our recurrent, intensifying crises. Two of the most important factors are the “three de’s” – deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization – and perverse executive, professional, and employee compensation. These two factors were principally responsible for creating the epidemic of mortgage fraud that drove our crisis. Financial regulation was effectively destroyed in the U.S.

The primary function of financial regulators is to serve as the “regulatory cops on the beat.” “Private market discipline” was an oxymoron – financial firms are supposed to provide the discipline by denying credit to poorly managed and overly risky firms. They are supposed to be impervious to fraud. The reality is that they fund the frauds’ rapid growth. Fraud begets fraud. George Akerlof warned of this perverse “Gresham’s” dynamic in his famous 1970 article about “lemon’s” markets. When fraud provides a competitive advantage market forces become perverse and drive ethical firms from the marketplace. Effective, vigorous financial regulation is essential to break this Gresham’s dynamic. The regulatory cops on the beat must take the profit out of fraud.

There are several reasons why the economic recovery is weak and there is a great danger of recurrent recessions. My colleagues on this blog have explained the macroeconomic reasons so I will concentrate on the regulatory barriers to recovery. Suffice it to say that my colleagues have shown that the recovery is not weak primarily due to credit restraints by banks on lending to corporations. The regulatory barriers to recovery are the opposite of what Romney asserts. Financial regulation in the U.S. remains extraordinarily weak. President Obama has largely kept in power and even promoted Bush’s financial wrecking crew. Larry Summers and Timothy Geithner are fierce anti-regulators. The Republicans have blocked vital appointments to the Fed – under the claim that a Nobel Prize winner in economics lacks sufficient expertise to serve on the Fed. The Republicans, while claiming that Fannie and Freddie pose a critical risk to the nation; have blocked the appointment of a superbly qualified head of the agency that is supposed to regulate Fannie and Freddie. The Republicans have blocked the appointment of Elizabeth Warren to head the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. Warren (a) warned of the coming nonprime disaster, (b) is superbly qualified to lead the bureau, and (c) is a remarkably pleasant and unassuming Midwesterner. The head of the SEC was named based on her experience as a failed leader of self-regulation. Bernanke named as the Fed’s top supervisor an anti-regulatory economist with no experience in examination or supervision. Bernanke then, absurdly, claimed that his appointment made the agency more inter-disciplinary. The reality is that it simply made theoclassical economists dominant in the one senior professional post that previously provided the Fed with an alternative policy perspective and real expertise. Attorney General Holder has largely continued the Bush administration’s policy of allowing the elite bank frauds to proceed with impunity.

The Republicans are trying to force severe cuts in the already inadequate budgets of the financial regulatory agencies. The flash clash revealed that the SEC does not have the internal capacity to monitor or even study retrospectively hyper-trading, which has become increasingly dominate. The SEC will not be provided with sufficient budget to even develop a system to monitor and study hyper-trading. The commodity markets are being subjected to exceptional manipulation. The Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has announced that it cannot afford to develop the systems essential to detect and track commodity speculation. Instead of demanding that the CFTC develop such an essential system the Republicans are seeking to slash the CFTC’s already grossly inadequate budget.

Romney’s claim that this group of understaffed and funded regulators led by senior anti-regulators constitutes “gargoyles” that have terrified the systemically dangerous institutions (SDIs) that dominate our finance system is ludicrous. There isn’t an SDI in the U.S. that fears its regulators. The regulators are like gargoyles – they may scare children but one soon learns that they are immobile stones that do not see, bite, or even growl. They are perches and canvasses for pigeons and their droppings.

Epidemics of accounting control fraud cause severe economic crises and harm recoveries in myriad ways. First, fraud causes far more severe losses. Second, fraud erodes trust because the essence of fraud is the creation and betrayal of trust. Trust can take many years to recover. The number of middle class Americans willing to invest in the stock market has still not recovered from the Enron era frauds. Third, as Akerlof & Romer (1993) warned, accounting control fraud epidemics can cause bubbles to hyper-inflate. Severe bubbles make markets grossly inefficient. Japan demonstrates that it can take over a decade for the prices to fall to levels where the markets will “clear.” The catastrophic nature of the losses and their concentration in financial institutions leads to the temptation to change the accounting rules to cover up the banks’ losses. We refused to do so during the S&L debacle and the result was a prompt recovery. We, like Japan, gave in to the banks’ demands during this crisis and the result is an impaired recovery. Fourth, the endemic mortgage fraud by lenders led to endemic foreclosure fraud because fraudulent lenders (a) keep extremely poor records and (b) a number of the largest servicers are staffed with personnel from the firms that made the fraudulent loans. The foreclosure fraud is harmful both because it defrauds the innocent and because it shields the most abusive borrowers from prompt foreclosures. Fifth, the fraud and the hyper-inflated bubble lead to a severe drop in private wealth and demand and household pessimism. The household sector has not been able to provide the demand to produce a strong recovery. Sixth, because we pretend that insolvent banks are healthy and keep them under the leadership of the inept and even fraudulent managers who caused them to become insolvent we end up with Japanese-style crippled banks that prefer to clip coupons rather than make commercial loans.

Romney is replaying the absurd and harmful propaganda of 1986-1987. S&L regulation was critically weak, which is what made the S&L industry so criminogenic. The industry trade association, however, claimed that regulation was oppressive. We, the S&L Federal Home Loan Bank Board Chairman Edwin Gray with any funds and any additional regulatory powers to counter the accounting control frauds that were running wild. Instead, in the Competitive Equality in Banking Act of 1987 (CEBA), Congress mandated “forbearance” designed to gut our power to close the frauds. This was not Congress’ intent – they did not consciously seek to aid the frauds. The worst S&L frauds, however, formed what a prominent CEO called a “Faustian bargain” with the S&L trade association to counter our proposed legislation. The result of that Faustian bargain was that language was inserted in our proposed bill that was framed by the frauds’ lobbyists for the express purpose of making it far more difficult for us to close the frauds. Until we took on their political patrons and spent months explaining to members of Congress, their staffs, and the media how the proposed amendments would damage our ability to act effectively against the frauds these claims that the regulators were ogres were taken as true by most politicians. All their political contributors said it was true. The reality was, of course, the opposite as virtually everyone now agrees. S&L regulation had been nearly non-existent. With the aid of Representatives Gonzalez, Leach, Carper, and Roemer and Senator Gramm (yes, that Senator Gramm!) we were able to make subtle changes in the CEBA bill that undid the worst of the frauds’ amendments.

Will the Obama administration be willing to fight like we did to save the effort to put the fraudulent S&Ls in receivership, remove the scam accounting rules, toughen regulation, and prosecute the fraudulent senior officers? Or will it give in to Romney’s propaganda and its desire to raise vast sums in political contributions from finance executives by weakening the already criminally weak Dodd-Frank Act? The administration’s most recent action has been to delay adoption of the rules implementing the Act. It wants banks to be able to continue the disastrous practices that made the crisis worse and that the Dodd-Frank Act sought to prohibit.

Here are the key passage and question arising from Romney’s speech:

“Almost everything the president did had the opposite effect of what was intended,” Romney said. “He said, okay, we’re not going to re-regulate the banking sector. Well, what he caused was the banking sector to pull back, and that’s the very sector that’s got to step forward to help get the economy on its feet again.”

The question to President Obama is: “Was Mr. Romney correct when he said that you decided not to ‘re-regulate the banking sector’?” And the follow-up question, if your answer is “yes” is: “If the Great Recession and the epidemic of bank fraud is not sufficient for you to reregulate the banking sector – what will it take?” Secretary Geithner and Chairman Bernanke state that the unregulated banking sector caused catastrophic losses and, but for extraordinary government intervention, would have caused the Second Great Depression. Effective banking regulation is essential to protect the public and honest banks. Both parties’ economic policies, however, are dominated by theoclassical economic dogma. Breaking the death grip of this criminogenic dogma on theory and policy is the economic profession’s most pressing need. Economists, and the politicians who find parroting their anti-regulatory policies so useful in raising campaign contributions, are the greatest threat to the economy.

[1] http://www.denverpost.com/headlines/ci_10473057 “Local Lehman arm led in Alt-A loans.” By Greg Griffin The Denver Post. Posted: 09/16/2008 12:30:00 AM MDT

The False Dichotomy between Banking Honesty and a Sound Financial System

(Cross-posted with Benzinga.com)

It’s exceptionally hard to kill bad ideas. The most spectacularly bad idea in economics and finance is that regulating business honesty is bad for business. The idea is exceptionally criminogenic. The idea ebbs briefly after each epidemic of control fraud it unleashes leads to crisis and scandal, but it quickly returns and intensifies. The bad idea has grown for three decades, which is why we have suffered recurrent, intensifying financial crises. Both major parties’ dominant economic policy makers embrace this bad idea.

Nothing is better for honest firms than effective police, prosecutors, and regulatory “cops on the beat.” These things make possible “free markets.” Fraud cripples markets. Criminologists know this. The best economists have known this for over 40 years. But really bright people explained why 285 years ago.

The Lilliputians look upon fraud as a greater crime than theft. For, they allege, care and vigilance, with a very common understanding, can protect a man’s goods from thieves, but honestly hath no fence against superior cunning. . . where fraud is permitted or connived at, or hath no law to punish it, the honest dealer is always undone, and the knave gets the advantage.

Swift, J. Gulliver’s Travels, London, Penguin (1967) p. 94. See Levi, M. The Royal Commission on Criminal Justice. The Investigation, Prosecution, and Trial of Serious Fraud. Research Study No. 14, London, HMSO (1993) p. 7.

As I’ve written, these words should be inscribed on the walls of every relevant regulatory agency.

George Akerlof echoed Swift’s words in a formal economics argument in his seminal 1970 article “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.”

“[D]ishonest dealings tend to drive honest dealings out of the market. The cost of dishonesty, therefore, lies not only in the amount by which the purchaser is cheated; the cost also must include the loss incurred from driving legitimate business out of existence.”

This is the article that led to the award of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001 to Akerlof. Akerlof went on to explain that fraud could lead to a “Gresham’s” dynamics in which bad ethics drove good ethics out of the marketplace.

The bad idea that rules designed to reduce business dishonesty harms business is premised on a false claim that markets automatically exclude fraud. Alan Greenspan is the most famous anti-regulatory who once held this view. He has, subsequently, admitted his shock at the financial fraud that defined the current crisis. He admits that his belief that markets automatically self-corrected by excluding fraud proved false. Frank Easterbrook and Daniel Fischel (1991) are the most famous proponents of the view that markets automatically exclude fraud: “a rule against fraud is not an essential or … an important ingredient of securities markets.” A generation of American law students has been taught to believe this theoclassical dogma. Easterbrook & Fischel did not alert their readers that Fischel had, in his consulting work on behalf of three of the leading control frauds of the 1980s, applied these dogmas to make a series of predictions. Those predictions proved embarrassingly false because Fischel did not understand accounting control fraud. He ended up praising the worst frauds and claiming that regulators were incapable of providing any useful information because the markets price already incorporates all useful information (he adopted a perfect markets hypothesis).

This false dichotomy between regulatory efforts against dishonest firms and improved market performance has particular importance given the ongoing attacks on Elizabeth Warren and the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The situation can be summarized briefly. Fraudulent loans hurt everybody who is honest and many of those who are somewhat dishonest. That’s what criminologists, the best economists, and effective regulators (plus geniuses like Swift) have long understood. I’m writing to a financially literate audience, so I do not need to explain that making fraudulent liar’s loans was never “profitable.” The reported “profits” were fictional and depended on either (i) making a fraudulent sale to another party or (ii) not creating a remotely adequate allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL).

The incidence of fraud on liar’s loans was so extreme, the number of liar’s loans made in 2004-2007 was so large that it hyper-inflated and extend the bubble, the role of fraudulent loans in causing the collapse of the CDO market was so great, and Lehman’s liar’s loans were so suicidal that reducing fraud should have been a top national priority. The fraudulent lenders and the loan brokers they incentivized to engage in endemic fraud put the lies in the typical liar’s loan – in the loan application and the appraisal. That meant that millions of working class people were induced by the lenders’ and their agents’ frauds to purchase a home at a greatly inflated price that they could not afford. The result was the greatest loss of working class wealth in modern U.S. history. Another result was that the lenders were made deeply insolvent. We achieved the precise opposite of what market transactions are supposed to produce – Pareto anti-optimality. Both of the parties to the lending transaction were made worse off. Many fraudulent agents gained. Markets became spectacularly inefficient and even failed. Much of the world fell into the Great Recession.

Private market discipline didn’t simply fail, it became doubly perverse. First, the commercial and investment banks that were supposed to deny credit to and refuse to purchase loans from fraudulent and imprudent firms actually funded the massive growth of the worst lenders notorious for making endemically fraudulent liar’s loans. Second, when private market discipline did finally occur it proved disastrous. Private market discipline arose when Lehman collapsed, but it did not function in accordance with finance theory. Theory says that private discipline is greatly superior to governmental action because it is so much more flexible and rational. It is supposed to distinguish between strong and weak credits and it is supposed to be so flexible that markets remain stable. The reality was far messier, with little differentiation based on credit quality among a broad group of potentially impaired credits and credit restrictions so severe that hundreds of markets ceased functioning.

The Great Recession caused losses estimated at $10 trillion. Fraud epidemics can cause staggering losses. What does this have to do with Elizabeth Warren and the FCPA? Elizabeth Warren was one of the experts who warned about the bubble and nonprime loans. Had the FCPA existed under her direction the U.S. would have suffered far fewer losses and could have avoided the Great Recession. Reducing mortgage fraud is unambiguously good for the world. Protecting consumers from mortgage fraud by banning liar’s loans would have led to a massive reduction in mortgage fraud.

Why then are the Republicans promising to block any appointment to head such a vital agency? We know it is not because of their stated reasons (hyper-technical diversions about commission v. director leadership) because the Republicans have typically favored directorship leadership in the past for other financial regulators (e.g., the Office of Thrift Supervision). We know it has everything to do with blocking Warren’s appointment. Senator McConnell says: “We’re pretty unenthusiastic about the possibility of Elizabeth Warren.” Why? Because he fears that under her leadership the CFPB “could be a serious threat to our financial system.”

Why can’t we appoint one leader with a track record of success? We’ve appointed many regulatory leaders with track records of failure. We’ve appointed many anti-regulatory leaders because they doing so created self-fulfilling prophecies of regulatory failure. The results have been disastrous. Why not try a novel approach? Let’s appoint people because they are brilliant, honest, committed to helping the public, and get the big issues right. Warren could have saved both banks and borrowers from hundreds of billions of dollars of losses had she led a CFPB in 2002-2008. We know that fraud causes recurrent, intensifying “serious threat[s] to our financial system.” Honesty poses no threat to our financial system. McConnell is posing a severe threat to our financial system by blocking Warren’s appointment.

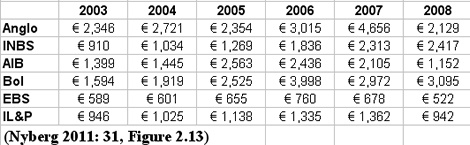

Control Fraud and the Irish Banking Crisis

This is part of a continuing series of articles on the European crises of the core and periphery. This column focuses on the causes of Ireland’s banking crisis. It begins by discussing what we know about modern financial crises in the West.

The leading cause of catastrophic bank failures has long been senior insider fraud. James Pierce, The Future of Banking (1991). Modern criminologists refer to these crimes as “control frauds.” The person(s) controlling seemingly legitimate entities use them as “weapons” to defraud creditors and shareholders. Financial control frauds’ “weapon of choice” is accounting. The officers who control lenders simultaneously optimize reported (albeit fictional) firm income, their personal compensation, and real losses through a four-part recipe.

- Grow extremely rapidly by

- Making poor quality loans at premium yields while employing

- Extreme leverage and