By Eric Tymoigne

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has just released an 8-page brief titled “Federal Debt and the Risk of a Fiscal Crisis.” In it you will find all the traditional arguments regarding government deficits and debt: “unsustainability,” “crowding out”, bond rates rising to “unaffordable” levels because of fears that the Treasury would default or “monetize the debt,” the need to raise taxes to pay for interest servicing and government spending, the need “to restore investor’s confidence” by cutting government spending and raising taxes. This gives us an opportunity to go over those issues one more time.

- “growing budget deficits will cause debt to rise to unsupportable levels”

A government with a sovereign currency (i.e. one that creates its own currency by fiat, only issues securities denominated in its own currency and does not promise to convert its currency into a foreign currency under any condition) does not face any liquidity or solvency constraints. All spending and debt servicing is done by crediting the accounts of the bond holders (be they foreign or domestic) and a monetarily-sovereign government can do that at will by simply pushing a computer button to mark up the size of the bond holder’s account (see Bernanke attesting to this here).

In the US, financial market participants (forget about the hopelessly misguided international “credit ratings”) recognize this implicitly by not rating Treasuries and related government-entities bonds like Fannie and Freddie. They know that the US government will always pay because it faces no operational constraint when it comes to making payments denominated in a sovereign currency. It can, quite literally, afford to buy anything for sale in its own unit of account.

This, of course, as many of us have already stated, does not mean that the government should spend without restraint. It only means that it is incorrect to state that government will “run of out money” or “burden our grandchildren” with debt (which, after all, allows us to earn interest on a very safe security), arguments that are commonly used by those who wish to reduce government services. These arguments are not wholly without merit. That is, there may well be things that the government is currently doing that the private economy could or should be doing. But that is not the case being made by the CBO, the pundits or the politicians. They are focused on questions of “affordability” and “sustainability,” which have no place in the debate over the proper size and role for government (a debate we would prefer to have). So let us get to that debate by recognizing that there is no operational constraint – ever – for a monetarily sovereign government. Any financial commitments, be they for Social Security, Medicare, the war effort, etc., that come due today and into the infinite future can be made on time and in full. Of course, this means that there is no need for a lock box, a trust fund or any of other accounting gimmick, to help the government make payments in the future. We can simply recognize that every government payment is made through the general budget. Once this is understood, issues like Social Security, Medicare and other important problems can be analyzed properly: it is not a financial problem; it is a productivity/growth problem. Such an understanding would lead to very different policies than the one currently proposed by the CBO (see Randy’s post here).

- “A growing portion of people’s savings would go to purchase government debt rather than toward investments in productive capital goods such as factories and computers.”

First, this sentence seems to imply that government activities are unproductive (given that, following their logic, Treasury issuances “finance” government spending), which is simply wrong, just look around you in the street and your eyes will cross dozens of essential government services.

Second, the internal logic gets confusing for two reasons. One, if people are so afraid of a growing fiscal crisis, why would they buy more treasuries with their precious savings? Why not use their savings to buy bonds to fund “productive capital goods”? Using the CBO’s own logic, higher rates on government bonds would not help given that a “fiscal crisis” is expected and given that participants are supposed to allocate funds efficiently toward the most productive economic activity (and so not the government according to them). Second, we are told that “it is also possible that investors would lose confidence abruptly and interest rates on government debt would rise sharply.” I will get back to what the government can do in that case, but you cannot get it both ways; either financial market participants buy more government securities or they don’t.

Third, this argument drives home the crowding-out effect. I am not going to go back to the old debates between Keynes and others on this, but the bottom line is that promoting thriftiness (increasing the propensity to save out of monetary income) depresses economic activity (because monetary profits and incomes go down) and so decreases willingness to invest (i.e. to increase production capacities). In addition, by spending, the government releases funds in the private sector that can be used to fund private economic activity; there is a crowding-in, not a crowding-out. This is not theory, this is what happens in practice, higher government spending injects reserves and cash in the system, which immediately places downward pressure on short-term rates unless the Fed compensates for it by selling securities and draining reserves (which is what the Fed does on a daily basis).

- “if the payment of interest on the extra debt was financed by imposing higher marginal tax rates, those rates would discourage work and saving and further reduce output.”

No, as noted many times here, all spending and servicing is done by crediting creditor’s account not by taxing (or issuing bonds). Taxes are not a funding source for monetarily-sovereign governments, they serve to reduce the purchasing power of the private sector so that more real resources can be allocated to the government without leading to inflation (again all this does not mean that the government should raise taxes and takeover the entire economy; it is just a plain statement of the effects of taxation). All interest payments on domestically-denominated government securities (we are talking about a monetarily-sovereign government) can be paid, and have been met, at all times, whatever the amount, whatever their size in the government budget.

- “a growing level of federal debt would also increase the probability of a sudden fiscal crisis, during which investors would lose confidence in the government’s ability to manage its budget, and the government would thereby lose its ability to borrow at affordable rates.”

If the US Treasury cannot issue bonds at the rate it likes there is a very simple solution: do not issue them. This does not alter in any way its spending capacity given that the US federal government is a monetarily-sovereign government so bond issuances are not a source of funds for the government. Think of the Federal Reserve: does it need to borrow its own Federal Reserve notes to be able to spend? No, all spending is done by issuing more notes (or, more accurately, crediting more accounts) and if the Fed ever decided borrow its own notes by issuing Fed bonds to holders of Federal Reserve notes (a pretty weird idea), a failure of the auction would not alter its spending power. The Treasury uses the Fed as an accountant (or fiscal agent) for its own economic operations; the “independence” of the Fed in making monetary policy does not alter this fact.

- “It is possible that interest rates would rise gradually as investors’ confidence declined, giving legislators advance warning of the worsening situation and sufficient time to make policy choices that could avert a crisis.”

It is always possible that anything can happen, but what is the record? The record is that there is no relationship between the fiscal position of the US government and T-bond rates. Massive deficits in WWII went pari passu with record low interest rates on the whole Treasury yield curve. With the help of the central bank, the government made a point of keeping long-term rates on treasuries at about 2% for the entire war and beyond, despite massive deficits. There is a repetition of this story playing out right now, and Japan has been doing the same for more than a decade. Despite its mounting government debt, the yield on 10-year government bonds is not more than 2% as of July 2010. In the end, market rates tend to follow whatever the central bank does in terms of short-term rates, not what the fiscal position of the government is.

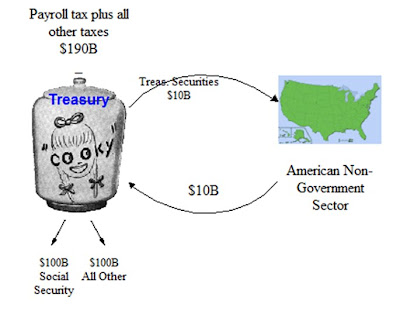

As we already stated on this blog before, a simple observation of how government finance operates shows that government spending injects reserves into the banking system (pressing down short-term interest rate), while the payment of taxes reduces/destroys reserves (pushing short-term rates up). The Fed has institutions that allow it to coordinate on a daily basis with the Treasury (they call each other every day) to make sure that all these government operations do not push the interest rate outside the Fed’s target range.

- “If the United States encountered a fiscal crisis, the abrupt rise in interest rates would reflect investors’ fears that the government would renege on the terms of its existing debt or that it would increase the supply of money to finance its activities or pay creditors and thereby boost inflation.”

That’s a repeat of the first question but with a bit of elaboration. The US government cannot default on its securities for financial reasons, it is perfectly solvent and liquid. (Sovereign governments can, as we have conceded on this blog, refuse to pay – e.g. Japan after the war – but that is because it was unwilling to repay, not because it was unable to pay.) Thus, despite Reinhart and Rogoff’s warnings, the credit history of the US government (and any monetarily-sovereign government) remains perfect. No government with a non-convertible, sovereign currency has ever bounced a check trying to make payment in its own unit of account.

The US government always pays by crediting the account of someone (i.e. “monetary creation”). If the creditor is a bank, this leads to higher reserves, if it is a non-bank institution it leads also to an increase in the money supply. It has been like this from day one of Treasury activities. It is not a choice the government can make (between increasing the money supply, taxing or issuing bonds); any spending must lead to a monetary creation; there is no alternative. Again taxes and bonds are not funding sources for the US federal government; however they have important functions. Taxes help to keep inflation in check (in addition to maintaining demand for the government’s monetary instruments). Bond sales allow the government to deficit spend without creating excessive volatility in the federal funds market. If financial market participants want more bonds, the Treasury issues more to keep bond rates high enough for its tastes; if financial market participants do not want more treasury bonds, the government does not issue to avoid raising rates. The US Treasury (and any monetarily sovereign government as long as they understand it) has total control over the rate it pays on its debts; whether the government understands this or not is another question. A monetarily sovereign government does not have to pay “market rates” in order to convince markets to hold its bonds. Indeed, it does not even have to issue securities if it does not want to. In the US, it is usually the financial institutions that beg the Treasury to issue more securities.

The recent episode of the “Supplementary Financing Program” is a very good illustration of that point. Financial market participants were crying for more Treasuries and the Fed could not keep pace. As a consequence the Treasury agreed to issue more Treasuries than expected to meet the demand and help the Fed drain reserves and thereby hit their interest rate target. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (DOMESTIC OPEN MARKET OPERATIONS DURING 2008, page 28): “To help manage the balance sheet impact of the Federal Reserve’s liquidity initiatives, the Treasury announced the establishment of a temporary Supplementary Financing Program (SFP) on September 17. The program consists of a series of Treasury bills issued by Treasury, the proceeds of which are deposited in an account at the Federal Reserve, draining reserve balances from the banking sector.”

Now look how this was deformed by the Treasury (quite a few journalists and bloggers followed): “The Treasury Department announced today the initiation of a temporary Supplementary Financing Program at the request of the Federal Reserve. The program will consist of a series of Treasury bills, apart from Treasury’s current borrowing program, which will provide cash for use in the Federal Reserve initiatives.” No, Mr. Treasury, this was not done for funding purpose; it was done to drain reserves from the banking system. The Fed does not need any cash from the Treasury. The Fed is the monopoly supplier of cash.

A final point regarding inflation. Inflation is a potential issue, as we have always maintained. But, there is no automatic causation from the money supply to inflation (a point Paul Krugman appears to have forgotten). Inflationary pressures depend on the state of the economy (supply and demand-side factors). Most importantly, perhaps, it depends on people’s desire to hoard vs. spend cash. Even the massive deficits during WWII, when resources were fully employed, did not lead to a spiraling out of control of inflation. Finally, it is quite possible that causation actually runs the other way around – i.e. from inflation to the money supply – given the endogeneity of the money supply, but that’s a story for another day…