Treasury and Central Bank Interactions

This post concludes our study of central banking matters (there would be a lot more to cover…maybe another time). The post studies how the Fed is involved in fiscal operations and how the U.S. Treasury is involved in monetary-policy operations. The extensive interaction between these two branches of the U.S. government is necessary for fiscal and monetary policies to work properly.

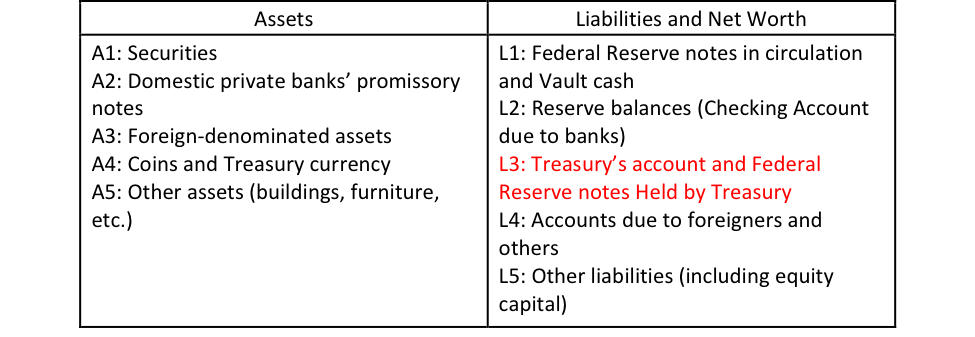

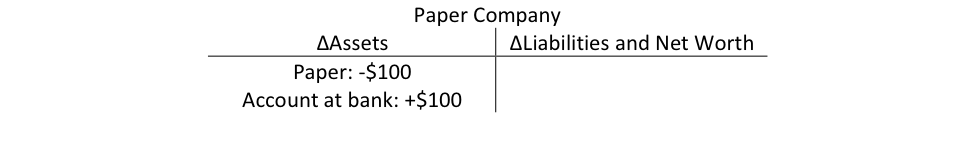

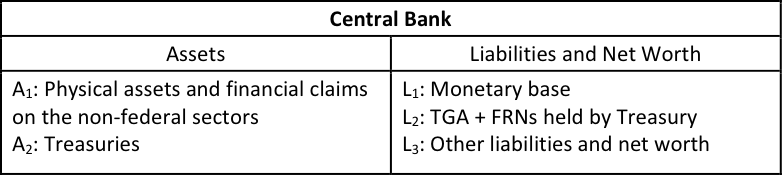

Once again the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve provides a simple starting point. The Treasury holds an account (called Treasury’ General Account, TGA) at the Fed, which is part of L3. To simplify, this post assumes that the Fed still follows the monetary-policy procedures that it followed prior to the 2008 crisis.

Monetary Policy and the U.S. Treasury

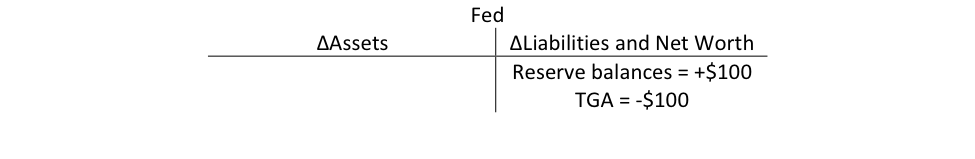

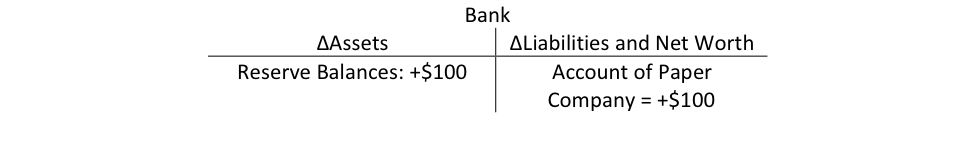

When Treasury spends, the Fed debits the TGA and credits the reserve balances of banks. Simultaneously, private bank credits the account of private economic units. Say the Treasury buys $100 worth of paper from a paper company.

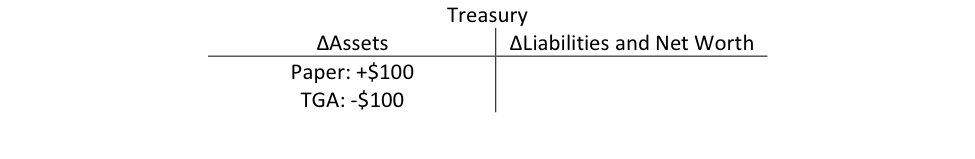

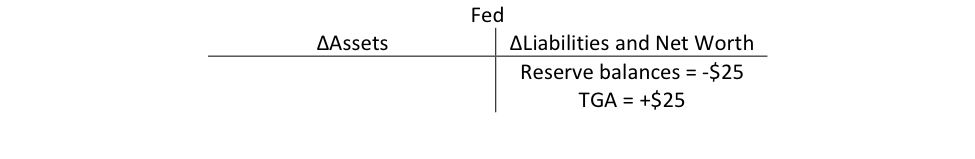

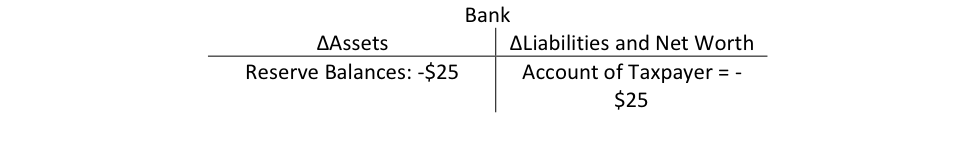

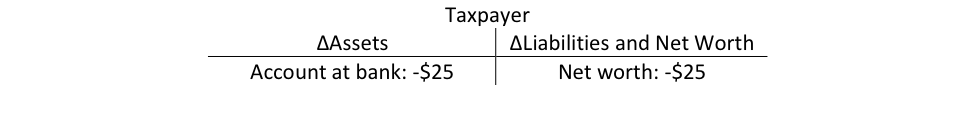

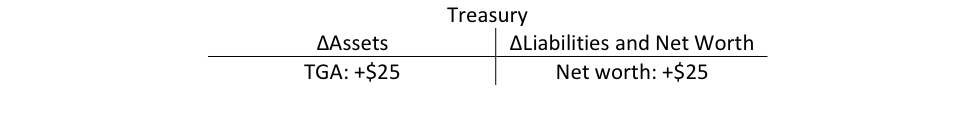

If Treasury receives $25 of income tax payments, the following happens:

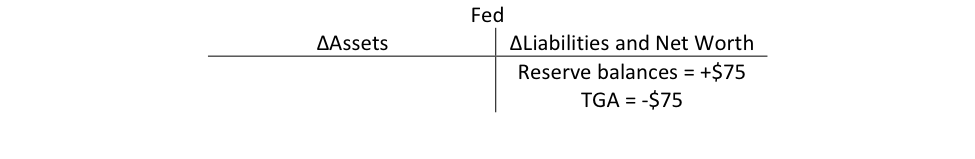

Therefore, in case of a deficit (taxes less than expenses), there is a net injection of reserves. The consolidation of the two previous fiscal operations is:

If the Fed does not neutralize the impact of the fiscal deficit by removing the extra reserves, banks will dump everything in the Fed Funds market and the FFR rapidly falls toward 0%. As long as the Fed targets a positive FFR, it has to neutralize the impact of daily fiscal deficits (L3 falls)—that lower the FFR—and the impact of daily fiscal surpluses (L3 rises)—that raise the FFR.

The Treasury understood the impact of its fiscal operations on money markets long before the Fed was created. In the current set up, the Treasury has helped the Fed to achieve its FFR target through two means:

- Cash management: The Treasury collects proceeds from taxes and bonds issuances in thousands of private bank accounts called the “Treasury’s Tax and Loan accounts” (TT&Ls). Treasury moves funds between its TTLs and TGA to help monetary policy.

- Debt management: The Treasury changes its outstanding debt, or changes the structure of its debt (proportion of short-term vs. long-term securities), for the purpose of helping monetary policy

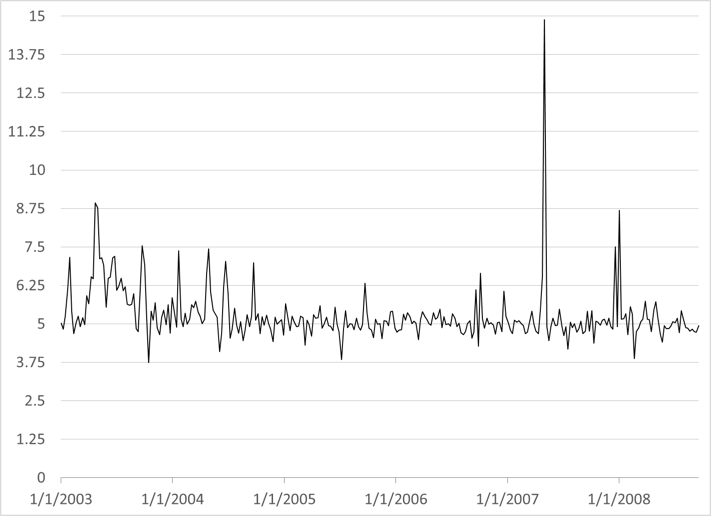

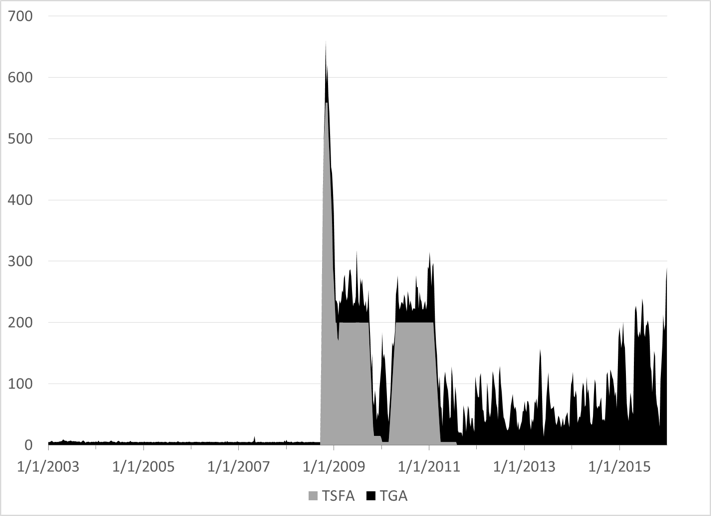

Given that fluctuations in the TGA (L3) influence reserve balances (L2), until the Great Recession the Treasury limited these fluctuations by keeping the TGA around $5 billion (Figure 1). Treasury employees met every morning with Fed employees to discuss the expected net cash flow on TGA for the day and to decide on the amount of funds to move in or out of TT&Ls to meet the $5 billion target.

Figure 1. Treasury’s General Account, weekly average until 9/17/2008, Billions of Dollars.

Source Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (H.4.1. series)

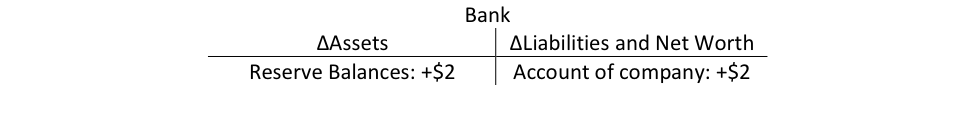

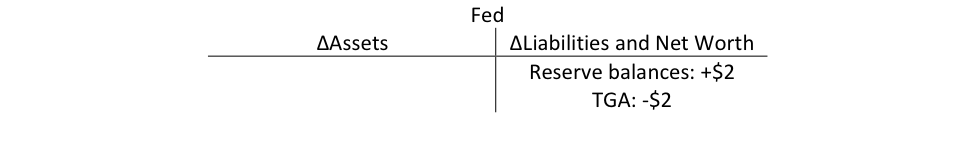

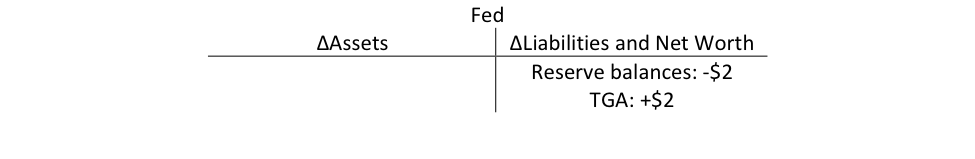

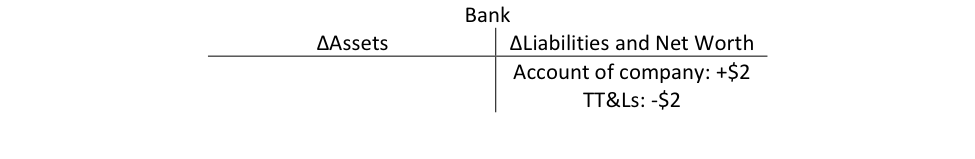

For example, say the TGA is currently at $5 and that this is the target of the Treasury. If the Treasury expects to spend $2, it would call $2 from its TT&Ls during the day. Cash flows of the TGA are very erratic throughout the day so they cannot be offset perfectly. Assume that spending occurs first (payment to a paper company):

The injection of reserves is removed by calling funds from TT&Ls:

So overall the net impact on reserve balances is zero and the balance sheet of the Fed is unchanged. The only change is on the liability side of private banks.

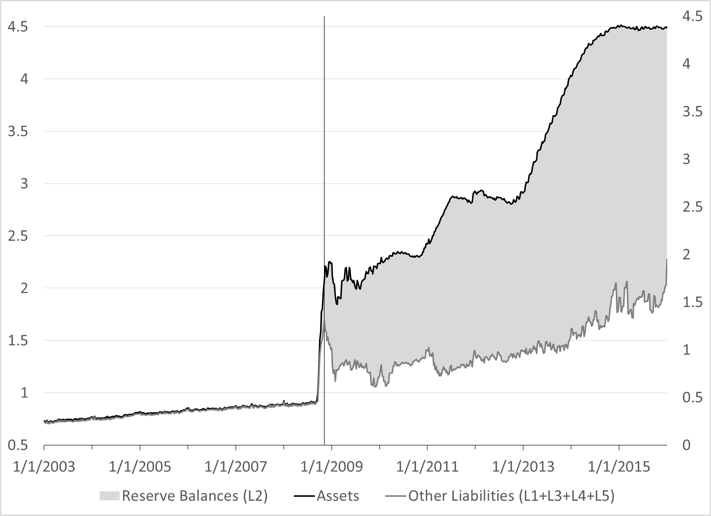

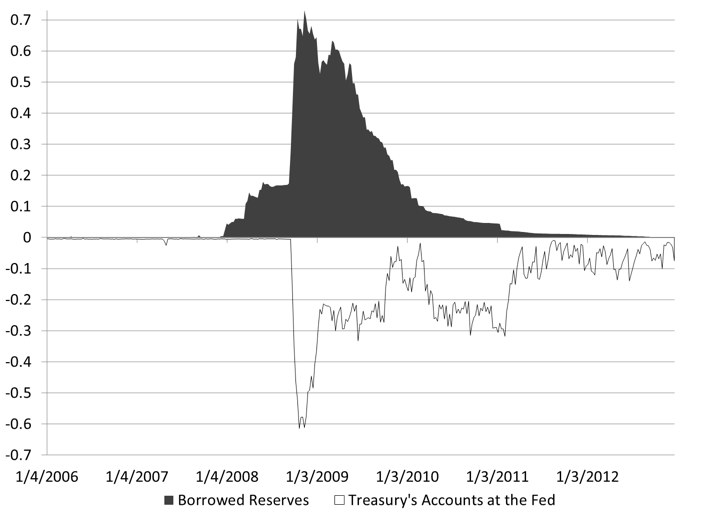

Lehman’s collapse in September 2008 led to a large injection of reserves but this injection was partly contained by a rapid increase in liabilities that peaked in value at $1.7 trillion on the week of November 5th 2008 (Figure 2a). The cause of the increase is a massive cash and debt management operation by the Treasury that started late September 2008. First, Treasury transferred tens of billions of dollars from its TT&Ls into the TGA, thereby breaking with its attempt to maintain TGA at $5 billion. Second, Treasury issued “Supplementary Financing Program” T-bills (SFP bills), and immediately put the proceeds into a new Treasury’ account at the Fed called “Treasury’s Supplementary Financing Account” (TSFA) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a. Balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, Trillions of dollars.

Source Federal Reserve (Series H.4.1)

Figure 2b. Treasury’s accounts at the Fed, billions of dollars.

Source: Federal Reserve (Series H.4.1)

Why did the Treasury do this? To help drain reserves in order to maintain the FFR on target. The FFR target was positive until December 2008, so reserves had to be drained in order to maintain the FFR around the non-zero target. Post 4 explains that the Fed had been neutralizing the impact of emergency programs on reserves since December 2007. It had been doing so by selling its holdings of treasuries to banks. In six-month the outstanding amount of treasuries fell from $780 billion in January 2008 to $480 billion in June 2008. If the Fed had continued to neutralize emergency programs in that fashion, it would have run out of treasuries very quickly with the panic of September 2008. It is all the more so that the Fed had started to lend some of its treasuries, so the amount unencumbered treasuries actually dropped to $250 billion.

In order to avoid that situation, the Fed asked the Treasury to help drain reserves via cash management (TT&Ls to TGA transfers) and debt management (issuance of SFP bills). The T-bills were issued at the request of the Fed for monetary-policy purpose (i.e. to help to drain reserves). The outstanding amount of SFP bills peaked at almost $560 billion in late October/early November 2008. After that the outstanding amount went down quickly for reasons explained below. Combined with its cash management operations, Treasury removed up to slightly more than $600 billion worth of reserves. As the Discount Window was advancing reserves to banks in difficulty, the Treasury was simultaneously draining them (Figure 3).

In its announcement of the Program, the Treasury misrepresented the purpose of SFP bills by stating that their purpose was to “provide cash for use in the Federal Reserve initiatives.” Of course this is incorrect because the Fed does not need cash from anybody, it creates cash.

Figure 3. Injection (+) and Ejection (-) of Reserve Balances, Trillions of Dollars

Source: Federal Reserve (Series H.4.1)

The Treasury rapidly reduced its help through the SFP program by agreeing to roll over only $200 billion of T-bills. Treasury did so because its help was no longer as needed (FFR target was at zero), and because of the debt-ceiling debate of the time that almost killed the program in early 2010.

Other examples of Treasury’s involvement in monetary policy

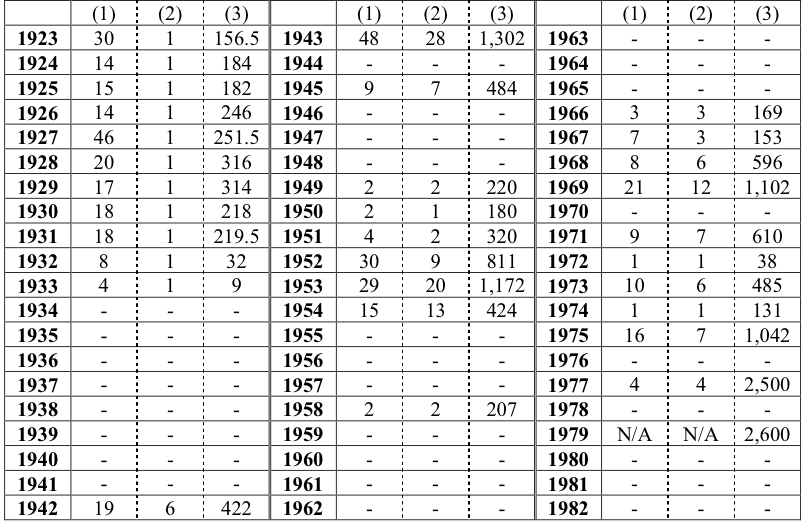

The Treasury has used other debt and cash management techniques in the past in order to help monetary policy. For example, Treasury used to be able to have an intraday overdraft on its TGA; unlimited from 1914 to 1935 and up to $5 billion from 1942 until 1979 (Table 1). As such, at times, the TGA would carry a negative balance during the day and, by the end of the day, the TGA would be replenished by direct financing of the Fed. The Treasury issued “special certificate of indebtedness” to the Fed and in exchange the Fed credited the TGA.

The Treasury used this overdraft authorization exclusively for monetary-policy purposes. For example, before a major tax season:

On occasion, the Treasury, in anticipation of heavy tax receipts during heavy tax months, will, under statutory authority, replenish balances at Federal Reserve Banks by borrowing directly from such banks through the issuance of special certificates of indebtedness, rather than withdrawing funds from Treasury tax and loan accounts. These funds are borrowed for only a few days and enable the Treasury temporarily to make disbursements in excess of its current receipts thus providing the banks with additional reserves in advance of a later unavoidable drain. (U.S. Treasury 1955, 282, italics added)

This allowed the Treasury to replenish its TGA without having to drain its TT&Ls. The Treasury did this not because it was running out of money:

At the time [Treasury’s administrators] have used the overdraft in the past, it has not been when they have had no balances with the banks. They have usually had very substantial balances with the banks. And they could have drawn on those balances to meet the overdraft. That, however, […] would be undesirable and unstabilizing to the money market to withdraw the [TT&Ls] for such a very short period of time. It would then build up unnecessary balances in the Reserve banks, and would create a deficiency of reserves in the banks throughout the country, and would compel them to sell securities or to borrow from the Federal Reserve banks (Eccles in U.S. House, 1947, p. 7))

Table 1. Direct Borrowing from the Fed: Number of Days Used (1), Maximum Number of Days Used at any One Time (2), and Maximum Outstanding at any Time (Millions of Dollars) (3)

Sources: U.S. House (1962), U.S. Treasury (1978), Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (1979)

Throughout most of WWII, the Fed was targeting the entire yield curve (i.e. all the interest rates on treasuries) and Treasury helped through debt management (Figure 4). The strict targeting of T-bond rate at 2.5% was relaxed a bit toward the end of the war, but Treasury and Fed still did not want the rate to deviate too much from 2.5%. After the war, fiscal surpluses removed T-bonds from the market even though there was high demand for them. This situation raised their price and yield on 10-year T-bonds declined steadily toward 2%. To bring back the T-bond rate up toward 2.5%, more T-bonds needed to be supplied. Unfortunately, the Fed did not hold enough T-bonds so the Treasury supplied more:

At any rate, the effect of a budget surplus at that time was terribly important in all of the monetary and debt management operations that went on. […] At that time, the Federal Reserve System owned practically no long-term Government bonds and, therefore, in its open-market operations was unable to supply the market with that type of investment. The Treasury Department, however, held large amounts of long-term bonds in various investment accounts. After consultations and discussions, both at a staff level and at a policy level, between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve and in full agreement, the Treasury Department, through the open-market committee of the Federal Reserve, sold large amounts of long-term Government bonds so as to fill the demand and to prevent a further decline in the long-term interest rate. During this period, the Treasury sold $1.5 billion of long-term bonds. However, the amount was not adequate to satisfy the demand nor to increase the market yield on such securities. Thereupon, the Treasury Department, after consultation with the Federal Reserve and with full agreement on the part of both, sold a nonmarketable 18-year issue in the amount of $1 billion. The purpose of this sale was to mop up any remaining investment funds that were exerting upward pressure on the market. (Wiggins in U.S. Senate, 1952, p. 227, p. 237))

From a fiscal perspective this seems strange—a Treasury trying to raise the cost of its indebtedness—but again all this was done for monetary-policy purposes, and more broadly for what was considered the social purpose.

Figure 4. U.S. Interest rates in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, Percent.

Sources: NBER, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Note: Grey area is represents U.S. official involvement in World War Two.

There has been other cash and debt management techniques used by the Treasury but those above should give you a sense that the Fed cannot do it alone given the way it operates in terms of monetary policy (it uses treasuries so Treasury must supply enough securities), and given that Treasury has an account at the Fed (a fiscal surplus/deficit drains/injects reserves). In other countries the institutional details change, but some coordination between Treasury and central bank is needed for monetary-policy operations to work properly.

Fiscal Policy and the Fed

For a government that has monetary sovereignty, i.e. issue its own currency and issued securities only denominated its unit of account, the central bank always helps one way or another to finance the budget of the Treasury. After all, central banks were created in part to help finance the state. Once again, the following focuses on the United States.

The most straightforward involvement of the Fed into fiscal operations was the availability of an overdraft on TGA until the late 1970s. As stated in the previous section, in practice this overdraft facility had been strictly used for monetary-policy operations, but it could be used for fiscal purpose in case of “national emergency.” The $5 billion limit was, however, very limiting for that purpose and there were Congressional hearings in the 1960s that looked into the possibility of expanding that limit and making the overdraft line permanent (authorization of the overdraft had to be renewed by Congress every two years). This never went anywhere because the use of the overdraft for fiscal purpose was seen as inflationary and unsound. The Treasury always justified the use of the overdraft as a brief and occasional means to finance its expenditures in order to avoid disruptions in the money market.

Even though direct financing was discouraged and later forbidden, the Treasury uses Fed’s monetary instruments to spend. Thus, one way or another, the Treasury will get financed by the Fed because only the Fed supplies the funds that the Treasury uses. While TT&Ls are used to receive bond and tax proceeds, they are just a tool that allow to smooth the impact of tax and bond proceeds on reserves. Ultimately all the proceeds go to the TGA, which drains reserves. As a consequence the Fed has to ensure that banks have enough reserves to allow the Treasury to be able to make the transfer from TT&Ls to TGA.

In addition, the Fed also has been heavily involved in treasury auctions (here is a video by two of my students for those of you that prefer a visual explanation) to ensure that they go on smoothly. Chairman Eccles again provides an insightful insider’s view on the financing of the Treasury:

[In past Congressional hearings] there was a feeling that […] Government [borrowing] directly from the Federal Reserve bank […] took off any restraint toward getting a balanced budget. Of course, in my opinion, that really had no relationship to budgetary deficits, for the reason that it is the Congress which decides on the deficits or the surpluses, and not the Treasury. If Congress appropriates more money than Congress levies taxes to pay, then, there is naturally a deficit, and the Treasury is obligated to borrow. The fact that they cannot go directly to the Federal Reserve bank to borrow does not mean that they cannot go indirectly to the Federal Reserve bank, for the very reason that there is no limit to the amount that the Federal Reserve System can buy in the market. […] Therefore, if the Treasury has to finance a heavy deficit, the Reserve System creates the condition in the money market to enable the borrowing to be done, so that, in effect, the Reserve System indirectly finances the Treasury through the money market, and that is how the interest rates were stabilized as they were during the war, and as they will have to continue to be in the future. So it is an illusion to think that to eliminate or to restrict the direct borrowing privilege reduces the amount of deficit financing. Or that the market controls the interest rate. Neither is true. (Eccles in U.S. House, 1947, p. 8)

If the Treasury does not get the funds it needs to implement Congressional mandates, and if Congress passes a budget in deficit, then the democratic process will not be fulfilled (the budget can’t be implemented), and interest rates will rise.

In terms of auctions of treasuries, the Fed makes sure they are always successful; “bond vigilantes” have no influence. The Fed has done so in many different ways, one way was to buy whatever was leftover during an auction. The Fed had to do so, either because until the 1970s T-bond auctions were not well established and so participation was not always as high as needed, or because the Fed was targeting the entire yield curve.

Now today in pricing a new Treasury issue, the Federal is in the position of underwriter. During the period of the offering the Federal tries to see to it that the Treasury’s issue is successful […] It stabilizes the market just the way any underwriter does. (Martin in U.S. Senate, 1952, p. 96)

Another way has been to provide a dependable refinancing channel to the Treasury because the Fed is still allowed to participate in auctions to replace its maturing treasuries.

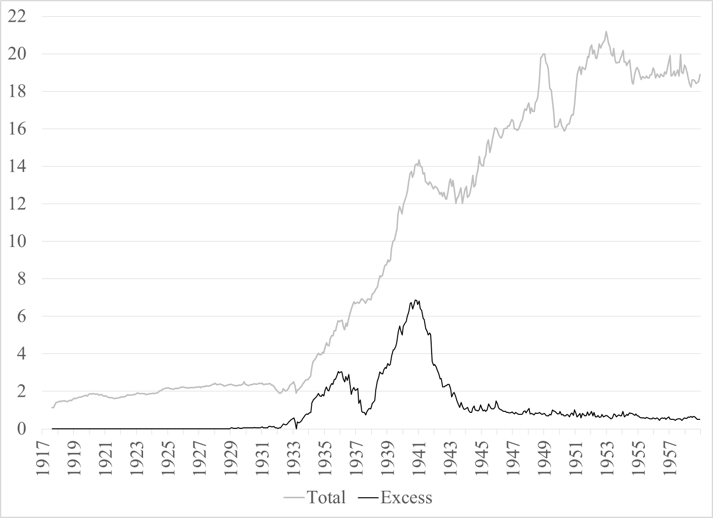

Finally, today the Fed participates indirectly in the financing of Treasury through the Primary Dealer System. During an auction, primary dealers must submit a reasonable bid and the Fed ensures that they have enough reserves at time of settlement by purchasing, or repoing, outstanding treasuries. Prior to the Primary Dealer System, the Fed also ensured that banks had enough reserves to settle an auction. For example during World War Two (See Figure 5 for reserve data during that period):

It was evident that all funds needed for financing the war which were not raised by taxation or by the sale of Government securities to nonbank investors would need to be raised by the sale of securities to the banking system. At first commercial banks were able to draw down excess reserves by several billion dollars, but later they had to be supplied with a considerable amount of additional reserve funds in order to purchase the necessary securities […] In general, further reserve funds were supplied by Federal Reserve purchases of short-term Government securities. (Martin in U.S. Senate, 1952B, p. 288))

Thus, one way or another the Fed will ensure that auctions never fail; and in the process it will be financing either directly or indirectly the Treasury.

Figure 5. Reserves, 1917-Aug. to 1958-Dec., billions of dollars

Sources: Banking and Monetary Statistics 1914-1941, 1941-1970.

A Necessary Coordination of Treasury and central bank activities

A Necessary Coordination of Treasury and central bank activities

The Treasury and the central bank must work extensively together for fiscal and monetary policies to work properly. The central bank cannot be fully independent from the Treasury:

The history of central banking, as was brought out earlier by the chairman, is that central banking cannot get too far away from the policies of Government too long; and that while central banks historically have won battles against the Government, they have always lost the war. (Wiggins in U.S. Senate, 1952, p. 235)

The central bank has independence of tools (interest-rate setting) and goals (inflation, etc.) but must work Treasury operations into its daily activities. Similarly, the Treasury needs to work monetary-policy considerations in its daily activities otherwise interest-rate stability would not be maintained and inflationary pressures could more easily materialize.

To go further: Consolidation or no consolidation? That is the question.

It should be clear from the previous sections that ultimately all the funds that the Treasury uses come from the Fed. While taxes and bond issuances debit the account of private economic units and credit TT&Ls, ultimately the Treasury needs funds in its TGA. And these funds cannot exist before reserves exist unless the Fed directly provides funds to the Treasury.

Pushing a bit further, it is quite clear that tax payments cannot be settled unless reserves are injected first in the banking system either by the Fed (through advances or purchases: assets go up, L2 goes up) or by the Treasury (via spending: L3 falls, L2 goes up). The same goes with proceeds from issuing treasuries. Monetary financing of the Treasury is not an option, it occurs one way or another. Either the Fed buys treasuries directly from the Treasury, or it buys them indirectly by first providing funds to primary dealers and then doing some outright or temporary purchases of treasuries.

Some economists following Modern Money Theory (MMT) have used these conclusions and noted that no analytical insight is gained from making a distinction between Treasury and central bank when dealing with a monetarily sovereign government. We might as well consolidate them into to one economic unit, the government. Consolidation is actually not infrequent in economic analysis, but MMT pushes for consolidation based on a detail analysis of the inner workings of Treasury and central bank relationships. It is a theoretical simplification that is grounded in a detailed institutional analysis. More importantly, MMT claims that consolidation has some implications for understanding the role of taxes and government-bond issuances for a monetarily sovereign government.

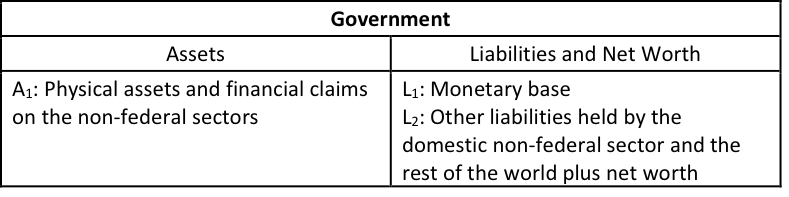

The balance sheets of Treasury and central bank look as follows (I use the word “currency” loosely here to mean all forms of central bank monetary instruments: cash and reserve balances)

Tax payments lead to:

- ΔL1 < 0: gov. currency is returned to the government

- ΔL2 > 0: higher net worth of government (or ΔA1 < 0, if a tax liability is on balance sheet, e.g. tax payable)

Government spending (fiscal policy) and advances (monetary policy) injects government currency: ΔL1 > 0.

Taxes do not fund the (consolidated) government, i.e. there is no crediting of a government checking account, no accumulation of funds by government: TAXES DESTROY GOVERNMENT CURRENCY (ΔL1 < 0). In addition, injection of government currency (ΔL1 > 0) MUST occur before taxing because tax payment is done by handing over to the government its currency (ΔL1 < 0). Exactly what was said in the previous sections.

Government-bond issuance leads to

- ΔL1 < 0: government currency is returned to the government

- ΔL2 > 0: interest-earning securities are issued

Bond issuances are equivalent to a transfer of funds from a checking account to a savings account. They are part of monetary-policy operations. The previous sections showed that this was illustrated in times of stress in the monetary system.

MMT authors tend to like to work with a consolidated government because they see it as an effective strategy for policy purpose (see next section), but also because the unconsolidated case just hides under layers of institutional complexity the main point: one way or another the Fed finances the Treasury, always. This monetary financing is not an option and is not by itself inflationary.

To go even further: What are the relevant questions to ask for a monetarily sovereign government?

An advantage of the “Tax don’t pay for anything” position is that it allows to frame existing debates differently. Instead of judging a program in terms of “how are we going to pay for it?”, one may now look at what the social needs are and figure out how to implement their production. That is the hard part. The financing of production is easy: it is always monetary financing one way or another.

Focusing the political discussion on tax and how or who will pay, who gets the benefits, etc. moves away from the public purpose of government and into an individualized benefit/cost analysis: “I paid tax, what do I get for it?” The simplest answer is maybe nothing because the purpose of government is not to benefit any specific individual but society as a whole. Or maybe an individual asking this question is too narrowly defining his/her benefits to their immediate, material and personal aspects. Some families may not have kids and so may not personally benefit from paying taxes for public schooling, but a better educated population has immense benefits now and for the future, which does impact the quality of life of all.

In addition, moving away from the “tax pay for” framework helps to better tackle some problems, simply because taxes for a monetarily sovereign government are not meant to pay financially for anything, but rather to free some resources (goods, workers, services, raw materials, etc.) for the public purposes. For example, the social security problem is not a financial problem; social security cannot go bankrupt. There is no need for a trust fund, no need to put dollars in a locked box, no need for payroll tax. Social security benefits can be paid the day they are due just by typing a number on the computer. The funds will come from debiting the TGA. TGA will obtain funds directly or indirectly from the Fed.

The hard part is figuring out how and what to produce to meet the needs of an aging society. We will need more infrastructure, workers, goods and services that cater to the needs of an older population, we will need to raise the productivity of available workers. That cannot be done by the Treasury saving dollars. Instead the Treasury should probably spend more on making schooling and training easier to access, and should provide some financial help to individuals and businesses willing to be involved in solving the problems of the future. The government should also be involved directly through infrastructure spending and others. All this means more federal government spending today, not less.

Taxes and tax structures are important but not for financing purpose but to promote price stability, to change behaviors and to correct arbitrary inequalities. Payroll tax does none of that. It raises the cost of labor, it discourages employment and it is regressive.

In the end the problem of paying for something is not a financial issue FOR A MONETARILY SOVEREIGN GOVERNMENT, it is a political and productive one. If congress is willing to do it, it will get funded; if it gets funded then comes the problem of finding the resources to implement the project. The really relevant questions are: “What do we want the government to do for us?”, “Do we want a government that represents 50% of GDP or 20% of GDP?”, “Do we want the burden of switching real resources to schooling, childcare, eldercare, etc. to be shared by society through higher taxes, or do we want to individualize that burden through higher personal expenses?”, “Do we prefer a society in which everybody fight for himself or do we prefer a cooperative society?” Once these questions are answered (hopefully through democratic process), the public purpose is clearly defined and the point becomes to implement it. Paying for its implementation in financial terms is easy, paying in real resources may be hard (especially at full employment).

Keynes’s How to Pay for the War is a classic example of the correct way to frame the question. He notes that: “A government which has control over the banking and currency system can always find the cash to pay for its purchases of home-produced goods.” The problem of how to pay is not a financial problem as long as goods and services are available for purchase in the denomination of the currency issued by the government. The problem is this at the time: “Every use of our resources is at the expense of an alternative use,” “the size of the cake is fixed.” There are opportunity costs and if nothing is done inflation will grow out of control as government competes with the private sector to access resources to fight the war. The problem is one of production and consumption. In peace time, the economy is usually below full employment so to produce more one just need to employ more. But at full employment, some choices must be made that involve giving up some alternatives and making sacrifices; that’s what “paying for” means. The private sector must sacrifice some consumption to free resources for government use. The question is who should sacrifice the most, how much sacrifice should there be, how should the sacrifice be implemented?

In the context of the war, priority are easy to set given the broad political consensus about what the public purpose is (winning the war): when three quarters of the cake used to go for private consumption, now only one quarter can go for that purpose. People have to live at subsistence level to be able to win the war. Government could try to achieve this through voluntary saving (war bond issuances), or by rationing, but the most effective way to achieve that is to cut purchasing power at the source: if people do not have as big a monetary income they will not go shopping as much. This can be done through taxing (permanent sacrifice of private consumption) or deferred pay (temporary sacrifice of private consumption), with the aim of reducing private monetary income to what is needed to meet subsistence.

While Keynes puts the choice in front of us in a blunt fashion given the dramatic situation of the time, the same applies in peace time. The two main differences are that, first, there is more flexibility in terms of resources given that usually the size of the cake can grow and, second, that a political consensus about the public purpose is less easily achieved. Of course, some countries that are monetarily sovereign may not have much resources and may not export much. In that case it is difficult, but not impossible, to implement the social purpose. If, in addition, a country is not monetarily sovereign, then implementing the public purpose is even harder.

That is it for today! Next few posts are about private banks.

[Revised 8/1/2016]

8 responses to “Money and Banking – Part 6: Treasury and Central Bank Interactions”