By Brian Hartley*

Modern banks are professional arbiters of financial IOUs secondary to that of the state or issuing authority. Central bank liabilities – reserves – form the most liquid and foundational instrument in the hierarchy of money, with intermediate obligations between banks ranking next, down finally to obligations issued by individuals. Banks facilitate the transfer of IOUs across and between various levels of the hierarchy, allowing transactions between individuals, extension of credit from the liquid to the illiquid, the transformation of maturities and transference of risk. Balance sheet expansion provides the liquidity necessary for increasing sophistication of the credit and payment system.

The endogenous ebb and flow of the balance sheet structure accommodates the tripartite nature of transactions in monetary capitalism. In the monetary circuit, goods buy money, money buys goods, but goods do not buy goods. In a monetary production economy, every transaction requires three parties to be carried out – a buyer, a seller and a third party that records the monetary consequences of the transaction in the unit of account. Money in this sense acts as a social convention that records the consequences of transactions – an artifact of the logic of accounting and a credit of the issuer. Banks facilitate monetary transactions in the simplest case by debiting the account of the purchaser and crediting the account of the seller. Indeed, it can be noted that nearly every transaction is as much a transaction between banks as it is a transaction amongst individuals. The identical process occurs when transactions are conducted in the fiat token of a sovereign currency issuer – as a liability of the central bank, the transference of the “money-thing” (cash) implicitly symbolizes a shift from one individuals “account” to another on the liability side of the central bank’s balance sheet.

This expansion of liquidity allows trading between agents and institutions that would otherwise be burdensome or impossible. The simplest example might be clearing a check for rent via correspondent banking, the maintenance of mutual accounts on the books of multiple banks that allows instant clearing between agents with accounts at differing institutions. Other trades are more complicated, such as exchange of real estate for cash to someone who attains funding from the issuance of a liability (a mortgage). This sale would likely have balance sheet implications for multiple banks, involve half a dozen or so transactions and may even require overnight reserve loans on the Fed Funds market or some equivalent to allow final settlement. Even relatively innocuous transactions are undergirded by a flurry of activity on the interbank market – and as modern capitalism advanced in sophistication, the complexity of the payment system followed by necessity. However, as in any system, complexity and interconnectivity invite fragility. The elasticity provided by the private banking sector alone was prone to panic, failures and uncertainty – whether by the bankruptcy of an individual firm or crisis of solvency or liquidity that might result.

The important question is of course the degree to which their IOUs are liquid and acceptable, and how this changes under different market conditions. One should point out that it is not only banks that can accommodate trade or issue credit – any agent can use their balance sheet in this fashion. Any agent or institution can attempt to spend by issuing liabilities, IOUs, but as Minsky said “the problem is getting them accepted.” The fundamental difference between banks and other economic agents is that banks operate with high leverage ratios. This can be measured in a number of ways, including debt-to-income as well as debt-to-asset ratios. Banks attempt to accomplish this safely by effective underwriting and evaluation of margins of safety. Occupying a uniquely risky position, banks must ensure income from assets exceeds commitments presented by liabilities as well as making sufficient collateral is available to finance shorter term liabilities should liquidity conditions become unfavorable. In essence, banks survive only to the extent they navigate the dual constraints of liquidity and solvency as their balance sheets shift over time.

The ability to survive with high levels of leverage enables relatively few specialized firms to allow the transformation of the maturity structures of financial claims for agents and institutions throughout the economy. Financial transactions are inherently two sided – every position in a trade requires an opposite position “on the other side,” all financial obligations net to zero. Commercial banks hold short term liabilities – deposits in the simplest case – and leverage them to acquire positions in longer term assets such as mortgages and loans to entrepreneurs. This allows households and other entities to take the opposite maturity position – typically holding long-term liabilities backed by short-term assets. This allows households and other institutions to better manage their financial holdings and claims – such as issuing a mortgage for housing that is funded by income flows. In addition, households and other agents are able to borrow quickly and conveniently at lower interest rates (Carney, 2). Money, and thus credit, are in a sense a “time machine” that allows transference of purchasing power (financial claims) across the life cycle of agents and institutions.

Many different types of financial institutions can be identified. Some specialize in holding long term assets with short duration liabilities, allowing the opposite arrangements to be made by households; others are market makers looking to collect fees. Commercial banks seek to make short term loans backed by strong collateral, preferably real goods. In this way banks can be the “ephor of capitalism,” whose funding is necessary for entrepreneurs to carry out investment and production (Wray, 6). The rise in the cost of required capital goods led to the investment bank, which would provide external funding for large-scale capital investment.

The universal bank model combines the two functions of the investment and commercial bank, whereas a Public Holding Company (PHC) whereby a variety of financial companies are owned with various legal provisions financially isolating one entity from another (Wray, 8). In each case, the past, present and future are connected by the various institutional structures and relationships that control the denomination of financial wealth (Minsky, 4).

As the regulatory structure began to be gradually dismantled in the decades following the period of post-war stability an unprecedented shift in the nature and conduct of financial institutions took place. Concentration and growth of the financial sector increased at a staggering rate, with even the distinction between industry and financial participants fading as large firms constructed highly profitable financial divisions. Financial sector credit market debt outstanding increased 12 fold from the early 70’s to 2007 to 120% of GDP (Nersisyan, 5-6). There was a shift in the finance sector away from traditional baking and towards market based funding for financial activities. Commercial banking shrunk from 60% of the economy in the Post-War period to around 25% before the crisis, with managed money taking the majority share (Nersisyan, 8). Increased market funding was accompanied by increasing leverage, and increasing dependence on continuous access to liquidity. There was a shift in emphasis from the amount of expected cash flows to collateral value of assets – and with the increase in importance of valuation the so called “trader mentality” began to dominate.

New financial innovations that allowed the “stretching of liquidity” accompanied these institutional changes. One principle development was securitization, the ability to package loans into a dizzying array of financial products that could then be packaged and sold on secondary markets. Banks could now “originate-to-distribute,” where specialized loans were sold in standardized packages in “arms length” conduits that were packaged into complex derivative contracts such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)(Carney, 3). To hedge against the risks of dealing in these complex instruments, entirely new classes of insurance called Credit-Default Swaps (CDS) were developed allowed institutions to offload default risk onto counterparties. Traditional insurance companies like AIG eagerly accepted the downside risk for wide varieties of derivatives contracts, expanding credit and providing fuel for ever increasing rounds of securitization.

How do these changes in the institutional structure of banking deal with the inherent risks associated with leverage and maturity mismatch? In theory, effective valuation, underwriting and risk management all continued to play a crucial role. Increasing the array of financial products and innovations allowed an expansion of liquidity, the ability to hedge and disperse risk. Highly efficient arbitrage markets bid prices to their “fundamental” values, promoting efficient risk allocation and making planning transparent. Entities that were ineffective at forecasting and managing balance sheets would be replaced by more capable firms. Even before the crisis, the effectiveness of relying upon “market regulation” alone was at best questionable, as evidenced by the regularity of banking panics in historical periods with the few non-market institutional controls. The establishment of FDIC insurance and the LOLR facilities represent such institutional constraints on the dangers that an unstable banking system poses.

The banking crisis of 2008 and beyond clearly indicates the need to develop new institutional constraints to ensure the healthy functioning of the financial sector. However, important theoretical impediments to reform remain. Despite the obvious failure of market regulation, the extreme form of market fundamentalism known as the “Efficient Market Hypothesis” that provided academic license for the excesses of finance is still being taught and advocated. Market efficiency and equilibrium still represent the “baseline” assumptions for mainstream economic models. The discourse necessary to promote effective financial reform is continually hamstrung by the intransigence of economists who still harbor conceptions of money and banking driven more by their pedagogical simplicity than by accuracy or theoretical coherence.

At the center of the mainstream vision of banking is the notion that money is a commodity that arose naturally in the response to the inefficiencies of barter. Accepting the barter origins of commodity-money immediately leads to the origin of modern banks. Hoarding the commodity-money accumulated during trade was subject to great risk of theft, and in response goldsmiths began to trade in their specialization of the safe storage of gold deposits. Once gold was handed over to the smith, the depositor would receive a certificate that entitled them to retrieval of the gold on demand. The smiths then realized that the depositors would not all attempt to redeem their gold at any one time, and began to loan out more redemption certificates than were covered by gold reserves at a profit. Competition drove innovation, and as the management of financial risk presented by the issuance of the deposit liabilities advanced in sophistication they evolved into modern banks.

The deposit multiplier implicit in the historical narrative above is the workhorse model of credit creation in mainstream theory. In the modern context banks are supposed to hold a proportion – the required reserve ratio (RRR) – of their deposit liabilities as assets on the balance sheet of the central bank. These reserves are liabilities of the central bank, which are supplied to the private banking system by either direct lending at the discount window or via Open Market Operations (OMOs). As reserves are injected, the broad money supply increases based on the size of the money multiplier, which is inversely related to the RRR. Under this view, banks are passive conduits of central bank policy, where reserves are a sort of “raw material” necessary for the extension of credit. That expansionary monetary policy could exogenously control the level of reserves led to a strong theoretical emphasis on the importance of monetary policy in the determination of output and inflation.

The supposed theoretical validity of this monetary transmission mechanism led the majority of the economics profession to mistakenly believe that Quantitative Easing (QE) would lead to a large increase in the broad money supply, a halt in private sector deleveraging and a resumption of long-term investment. Yet unprecedented monetary expansion did nothing to increase the broad money supply, excess reserve ratios simply skyrocketed as banks accumulated reserves. Some experts wondered if “the money multiplier had collapsed,” while still more worried that the massive accumulation of bank reserves was an inevitable harbinger of future inflationary pressure (Sheard, 3).

To understand why the monetary policy transmission mechanism failed, and the fears of inflationary pressure are unjustified, we must first examine how central banks create reserves. Consider a simplified version of a central bank balance sheet:

Assets (A) = Reserves (R) + Banknotes in Circulation (BK) + Government Deposits (GD)

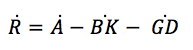

After rearranging terms, this becomes:

Thus, the rate of change of reserves is equal to the change in assets minus the change in banknotes and government deposits. The amount of reserves liabilities in circulation can only increase if central bank purchases assets, the public wishes to hold less banknotes or the treasury makes a net transfer from the account at the central bank to the private sector (Sheard, 5-6). None of these transactions involves private sector lending! In fact, if we assume that the BK and GD remain constant, the amount of reserves outstanding is determined entirely by the level of central bank asset purchases.

If not by drawing down reserves, how do private sector banks actually lend? Quite simply, they lend by simultaneously expanding both sides of their balance sheets, with reserves playing no substantive role. Now let us consider the simplified balance sheet of a private bank:

Reserves (R) + Loans (L) + Bonds (B) = Deposits (D) + Equity (E)

Consider the operational realities of loan origination – a loan officer doesn’t check reserve balances before a loan is extended; the principle concern is the creditworthiness of the borrower. The loan is extended independently of reserves, whereby a deposit is simultaneously created, and the fulfillment of the reserve requirement will be met on the interbank market (if necessary) at a later date. Loans are not made out of reserves or deposits; in fact, loans create deposits. Notice that other rates of change equal to zero a change in loans will be matched inversely by a drop in reserves, that is, loans may be increasing while reserves are falling. But note that the causality does not flow from the private bank; discretionary decisions must be made at the level of the central bank, the public or the treasury for this to occur (Sheard, 7).

What do reserves then have to do with credit creation? Quite simply, they allow depositors to withdraw cash balances, with the rest of their deposits left as liabilities of the private banking system. Thus, new reserves only fall as a direct result of credit creation to the extent the aggregate level of cash balances held by the public increases. Neither does the level of deposits drive credit creation – deposits are created by a combination of lending and net inflows from the central government (deficits) (Sheard, 8).

Given the presence of demand for cash balances and RRR, the level of outstanding reserves still might be envisaged as a constraint on credit creation, if not a raw material for it. However, this is untrue for the banking system in aggregate because the level of reserves is not a discretionary variable from the perspective of the central bank. As long as the Fed intends to maintain par clearing on the interbank market, as well as hit the FF target, the amount of reserves it issues is endogenously determined by the interbank market. The normal causal process taught in money and banking textbooks is exactly backwards – credit is not “pushed” into the economy, reserves are “pulled” out of the central bank in accommodation of a demand-driven process. That banks are essentially unconstrained in this manner illustrates the poverty of the neoclassical approach, which at best treats banks as intermediaries and credit creation or debt-deflation as having only distributional significance.

When one recognizes credit creation is an inherently endogenous process within capitalism, the ineffectiveness of monetary policy becomes apparent. Central bank asset purchases, though perhaps useful for temporarily stabilizing financial markets, will not stimulate credit creation by increasing reserves. With the level of reserves having been shown to be irrelevant, other influences of QE and ZIRP would have to bear the key responsibility for increasing aggregate demand. Compression of the yield curve and the associated increase in coupon values of fixed income assets – the so-called wealth effect – would likely have stimulative impact on spending and investment. However, the decrease in earned interest income, a source of net financial income for the private sector is reduced. In the face of uncertain and contradicting effects, the impact of QE and ZIRP on aggregate demand is of indeterminate sign and likely small – this certainly has been consistent with the experience of similar attempts in countries like Japan.

The focus upon monetary rather than fiscal policy for delivering recovery is thus confused and wrongheaded. This lays out the first, and perhaps most important proposal for financial reform offered in this article. Policy makers should not delegate the responsibility for recovery onto central banks that do not possess the powerful tools ascribed to them. In addition, the unforeseen consequences of unprecedented balance sheet expansion should be weighed against its obviously minimal benefits. Fiscal policy, with its direct and immediate effects upon aggregate demand, should and must bear the key responsibility for recovery. Central banks still have a crucial role to play – however it concerns the legal authority these institutions possess to enact structural oversight.

The financial system had clearly evolved into a set of institutions where these key beneficial responsibilities of a healthy banking sector are being directly threatened. At best, the increasing dominance of pecuniary motivation among financial participants have relegated the socially vital roles of maintaining the payments system and conducting responsible underwriting of secondary importance. Understanding the nature and dangers of financialization can be fruitfully viewed within the context of Minsky’s typologies of types of capitalist development, as well as his outline of the destabilizing properties of financial competition proposed by the Financial Instability Hypothesis. Keeping this theoretical framework in mind, we can then turn to the specific institutional changes that have come to pass in what he presciently called “Money Manager Capitalism” and potential reforms that might mitigate its dangers.

Minsky described the first stage of capitalist development as “commercial capitalism,” in which external finance is used mainly for trade in real goods and service, similar to the “real bills” doctrine (Minsky, 4). Next is “industrial” or “paternalistic” capitalism in which the increasing need for expensive capital goods requires external financing for long-term investment. Paternalistic capitalism was characterized by counter-cyclical fiscal policy, deposit insurance and increased government intervention in the economy. The era of the “Big Government” and “Big Bank” was marked by great stability and prosperity; this increasingly led to a multi-decade long process that created “money-manager” capitalism – whereby the many differing types of financial institutions would converge in function and structure.

These developments led Minsky to propose what was known as the Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH), where by the “normal” processes of market competition led to increasing fragility in the financial sector. Banks could be thought of as engaging in three distinct types of behavior, hedge, speculative and Ponzi. Hedge units are those that can fulfill all of their liabilities from cash flows alone, and are the safest most stable type of financial units. Less stable are speculative units, whose cash flows can only meet the servicing costs of their commitments and not the principle value. Ponzi units are the most unstable; as they need to issue new liabilities just to service the commitments already on the books. In each case, the unit offers lower and lower margins of safety to those financing it. The greater the amount of speculative and Ponzi strategies being employed, the more likely the competitive market economy will be a “deviation amplifying” rather than “equilibrium-seeking” system (Minsky, 7).

The second general proposition of the FIH is that over long periods of stable growth and prosperity, capitalist economies would tend to move from a financial system dominated by hedge firms to ones dominated by Ponzi firms. This can be a result of expectations – that backward-looking firms will “forget” about past crisis and increasingly engage in risky behavior out of fear that under-investing relative to their competitors will lose them profits. A rush to liquidity can trigger a drop in asset values and debt-deflation as firms attempt to “make position by selling out position” (Minsky, 8). Also, provisions put into place to stabilize capitalism, such as central banks with Lender-of-Last-Resort facilities can cut short debt-deflations after crisis, allowing the natural tendency of the financial sector to create greater amounts of private debt to accumulate in the long run despite panics. Paradoxically, the stabilizing influence of government intervention can create fragility in the long term, while also lending an inflationary bias to the economy. The subsequent control of inflation by contractionary monetary policy may shift newly created speculative firms into a Ponzi state. “Stability is destabilizing,” and in both the expansion and bust, “rational” market competition and the profit motive create feedback loops instead of equilibration.

The increasing fragility can also be understood as financial firms in aggregate accepting decreasing “margins of safety,” or the buffer stock that must absorb errors about the anticipated return on investment. The margin would also include the protection of any factors that would allow recover of value from a project, such as collateral or deposits (Kregel, 8). The common use of historical data to train valuation models or more simply to use past performance in underwriting suggests agents are backward looking – this can lead to successively lower margins of safety during speculative booms. Of course the factors that determine realized future returns are subject to radical uncertainty, and in response agents must by necessity employ procedural rationality of some form, usually taking the actions of other agents as useful guides to “best practices.” This inevitably contributes to the herding behavior that characterizes unstable disequilibrium processes.

In many important respects, the long run buildup towards increasing fragility in the financial system, and the subsequent credit crunch largely reflected the insights offered by the FIH. The economy in 2007 had clearly been in the “money manager” stage of capitalism for some time, with the amount of privately managed funds and mutual funds dominating an unprecedentedly large FIRE sector. Sections of the Glass-Steagal act that were supposed to prevent commercial banks of engaging in risky activities were loosened and eventually abandoned (Kregel, 10). This development was of course secondary to the collapse of underwriting and pervasive culture of fraud throughout the real estate industry. The rise of securitization and the collusive practices of originators and rating agencies allowed prudent underwriting standards to be abandoned in favor of “pump-and-dump” short-termism. The “trader mentality” was pervasive – with propriety trading profits at large investment banks soaring, and the implicit backing by LOLR facilities and deposit insurance being increasingly perceived as covering even SIVs and other entities that appeared more like hedge funds than traditional banks (Wray, 11). Income flows became less relevant, as debt-to-asset ratios and reliance upon the self-fulfilling prophecy of asset-price appreciation drove capital leverage ratios skywards to 30 to one hundred times and beyond (Wray, 14-15). The perpetual “stretching of liquidity” was a direct result of competitive processes – including increasing pressure from shadow banks and other SIVs that were providing new and unregulated forms of financing.

Quite clearly, the buildup of systemic risk and the subsequent collapse in the “Minsky moment” of the credit crunch had enormously destructive social consequences. The public subsidization of non-performing loans originated with bad and often fraudulent underwriting resulted in widespread resource misallocation (Wray, 7). Enormous social and psychological costs are suffered by homeowners who are forced to foreclose, go underwater, or suffer reduced property values. Commodity price volatility caused in large part by mutual fund speculation caused difficulties for the many firms and households highly dependent those prices. Perhaps worst of all are the effects of under-employment and lost output due to the subsequent recession, and the failure of policy makers respond adequately. Each of these effects was a direct consequence of the competitive process, not the result of an aberrant deviation from “market principles.”

When the bubble finally burst, and the extent of the dangers of financialization finally became known, there was a genuine impulse among the mainstream for systemic reform. Deregulation and unrestrained markets had obviously failed and an angered public clamored for change. Various measures were proposed and some enacted, including the Dodd-Frank Act as well as the so-called Volcker Rule. Much of the public anger was directed at the perceived inequity of the bailouts, and likewise much of the reform for directed – at least nominally – at reducing the influence of systemically important institutions.

After 5 years of opportunity for redress, the excesses of the financial sector show no sign of abatement. The largest banks are now more concentrated than ever before, FIRE sector profits are rising as a proportion of GDP, and executive pay is still astronomically high, with the average Goldman employee set to earn over 700k in bonuses per year on average (Nersisyan, 21). There have still been no criminal prosecutions for fraud directed at the finance industry, despite evidence of massive and pervasive fraud. Indeed invulnerability of bankers to prosecution reached tragi-comic heights when HSBC avoided any criminal indictments of staff despite admission of participating in the laundering of over 670 Billion of suspicious wire transfers from countries with terrorist and drug trafficking ties. Apparently prosecuting even low level money laundering compliance officers was enough to threaten a “systemically important institution,” and thus the financial sector as a whole. It is quite difficult to overstate the offense such arrangements give to the principles of democratic and legal accountability. However, such scandals make the toxic nature of the existence of such “systemically important” private institutions painfully obvious.

More effective financial reform is needed, but by what criteria should we judge its efficacy? For Minsky, the key role of banks and the financial sector was always to promote “capital development,” agreeing with Institutional economists that such development should be understood as enhancing the social provisioning process. Though both static and dynamic efficiency are important considerations for the evaluation of the state of the economy and potential reforms, ultimately social efficiency should be the predominant goal. Growth, low employment, and stable prices are worthy objectives, but enhancing talents and capabilities should also be emphasized (Minsky, 8). Fortress capitalism must be replaced with shared-prosperity capitalism (Minsky, 9). Though efficiency and equality may in some instances be at odds, for the most part they are not, with security and prosperity reinforcing one another.

Some have proposed a return to narrow banking, or even full-reserve banking. However, reforms that simply narrow the responsibilities of the financial sector to deposit taking and lending are also inadequate. Though potentially addressing the need to place a firewall around the payments system and the role of traditional banking, narrow banking proposals do not address the diverse roles that financial entities now play concerning capital development. The vast majority of financial activities that banks engage in are ignored, such as their role in international trade and finance, market-making and corporate underwriting, as well as the systemic importance of non-traditional financial units like shadow banks and SIVs. The new regulatory initiatives must be macroprudential; deployed across multiple fronts engaged against the broad proliferation of institutions, risk categories and market structures (Carney, 7).

In short, financial sector reform should be a holistic effort aimed at creating what Henry Simon first called “the good financial society.” Many of these institutional adjustments have already been established by the New Deal reforms and before and followed through in the crisis. LOLR facilities form the foundational protection against the dangers of financial panics and debt deflation – but the continually saving private financial interests creates instability in the long-run. One way to forestall this is to increasingly exercise qualitative credit controls by limiting the trading in certain classes of speculative assets, such as exotic derivatives (Minsky, 14). This proposal has been echoed by many other commentators, who call for a new regulatory branch similar to the FDA to approve new financial instruments before they are allowed to be traded, and to ensure that the trading is transparently monitored on centralized exchanges. Qualitative controls could channel investment towards the public purpose, and besides increased transparency, trading on centralized exchanges could also allow for a greater proliferation of market governing institutions to rationalize potentially unstable competitive processes. Specifically these constraints would combat the destructive influence of shadow banks and SIVs which many mainstream reform efforts do little to address.

Douglas Diamond said that “financial crisis are always and everywhere about short-term debt.” That is, financial panics always result from the maturity mismatch of long-term assets and short-term liabilities among market participants – the individual need for liquidity and the impossibility of liquidity in aggregate (Ford, 67). Like most vexing problems in economics, the acquisition of liquidity is subject to a fallacy of composition; one institution’s flight to safety has to be mutually offset by equal and opposite maturity positions by another. Former Treasury Secretary Morgan Ricks has proposed that systemically vulnerable institutions be forced to “term-out” their liability structure in accordance with assets. Creditors in this case would be locked into long term bets on such institutions, but the ability of non-bank institutions to have long-term liabilities balanced by short-term assets (typically income flows) might be diminished.

Community Development Banks (CBDs) of various forms could also offer financial services to different localities without reliance on the fragility promoting aspects of money manager capitalism. These banks would be encouraged to promote local development and loans to small businesses, which makes the income flows of local communities more integrated and robust to financial volatility (Minsky, 15). They would function as public-private partnerships that would provide financial services to households that often do not have access to them outside of the large and vulnerable banking institutions. CDBs might also be synergetic with other proposals such as cooperative banking and credit organizations and Local-Exchange-Trading-Systems (LETS).

During the crisis, the unprecedented level of cooperation and mutual assistance between central banks highlighted the importance of international institutions that promote healthy financial development. But where many of the deals between central banks were reached with little explicit institutional backing, Minsky, following Keynes, desired to design an international LOLR with explicit legal grounding. The current flexible exchange rate regime encourages “dual deficit” problems in which countries deal with trade imbalances by imposing austerity – “surplus-recycling” mechanisms to address trade imbalance need to be developed at an international level (Minsky 15-16). Proposals similar to this can of course be found in Keynes, but analogous proposals to correct trade imbalances are common (such as the Varoufakis-Holland plan for the EU) yet often politically nonviable.

Ultimately, the size of the financial sector will have to be reduced substantially. Clearly the power of managed money has contributed to many different financial problems, from the savings-and-loan debacle of the 1980s to the commodity boom driven by portfolio optimization efforts. Open IRAs might provide an alternative investment vehicle to compete with the quasi-public money management industry (Wray, 32-33). Of course, building shared-prosperity capitalism must also require numerous institutional adjustments outside the financial sector, including greater public investment, a form of employer-of-last-resort (ELR) program and greater public-private cooperation. The declining wage share and increasing contribution to GDP of the FIRE sector, even after the crisis, need to be addressed directly via structural reform.

Every financial institution that is deemed “too big to fail” (TBTF) should immediately be broken into smaller, more manageable entities. The entire notion of TBTF is offensive to legal and democratic accountability, not to mention basic pragmatism in public administration. Such organizations pose an existential threat to the health and viability of the financial sector and the economy at large and should be downsized immediately. Balance sheets should be consolidated (including positions on derivatives) to determine solvency. Institutions would then be resolved in accordance with the cost to the FDIC as well as the ease of downsizing (Nersisyan, 24). During the transition, salaries at insolvent institutions would be at best commensurate with the compensation received by other technical administrative staff at public institutions. Uninsured losses that accrue to other financial institutions would in large part have to be reimbursed.

The role of even a robust private banking system free of systemically important institutions in the maintenance of the payment system needs to undergo radical reexamination. This role provides perhaps the most obvious justification that banks are quasi-public intuitions, rightly subjected to democratic control and scrutiny. The current system requires agents to employ banks to facilitate transactions between one another, ultimately backed by the various Federal provisions and institutions. However, there is no particular reason the payments system needs to be run in the private sector at all – economic agents would need only to have their own accounts at the Fed. This acts as yet another de facto subsidy to the private banking sector, but does offers no particular benefit that having a basic public payment facility would not. Such a public facility could be run quite cheaply and securely at the Federal Reserve, conducted in concert with CDBs or run similarly to postal saving services that have already been established in many countries.

The state could also provide the underwriting services that are commonly assumed to be more effectively handled by the private sector. Despite recent evidence to the contrary, this presumption has merit. In a healthy and well regulated private banking system there are strong incentives to engage in strict underwriting with well understood and low risks of default. To the extent they are directly liable for the performance of loans; private sector lenders may not be as subject to the nepotism and cronyism of state bureaucracies. Extension of public credit is best directed democratically and conducted transparently – where the institutions to ensure these criteria are absent, credit extension may be best provided in the private sector. However, in cases where there are clear public benefits to expanding credit the dangers of higher default rates are small. As Keynes argued, an important part of financial sector reform is the expansion of public sector investment and credit expansion into socially vital sectors. These might include expanding public student loan subsidies, the establishment of public infrastructure investment banks, and other forms of credit extension into publically vital efforts. Such efforts could help provision important services as well as smooth the volatility of investment contribution to aggregate demand.

Achieving the “good financial society” will a shift in the core aim of the central bank from monetary policy towards financial regulation and supervision, forming a range of entities that can provide key financial services in a manner conducive to the public purpose as well as develop new institutional constraints to limit financial fragility. Systemically important and insolvent firms need to be resolved; the dangerous tendency towards liquidity and solvency crisis needs to be addressed with qualitative as well as quantitative regulation encompassing the new range of exotic innovations currently unaddressed by public policy. Most importantly, a new economic discourse that rejects the baseline assumption of self-regulating markets needs to be vigorously taught and advocated.

*A Note:

For the next few weeks we will be running a series of articles on monetary theory and policy. These are final essays written by MA students in my class this past Fall semester. I was very happy with the results—students indicated that they had a firm grasp of both the orthodox approach as well as the heterodox approach to the subject. Most of them also included some Modern Money Theory in their answers. I asked about half of the students in the class if they would like to contribute their essay to this series. Sometimes students are the best teachers because they see things with a fresh eye and cut to what is important. They are usually less concerned with esoteric academic debates than are their professors. Note that these contributions are voluntary and are written by Masters students. I told students they could choose to use their own names, or they could choose an alias. Comments are welcome, but please be nice—remember these are students.

For your reference, here were the topics for the paper. The paper had a maximum limit of 6000 words.

Choose one of the following. You must consider and address both the orthodox approach and the heterodox approach in your essay. Where relevant, include various strands of each.

A) What is the nature of money? Given the nature of money, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

B) What is the nature of banking? Given the nature of banking, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

C) According to John Smithin there are several main themes throughout controversies of monetary economics, each typically addressed by each of the various approaches to monetary theory and policy. In your essay, discuss how each of the approaches we covered this semester tackles these themes enumerated by Smithin.

L. Randall Wray

Sources

Carney, Mark. “What are banks really for?” Remarks by Mr. Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of Canada, to the University of Alberta School of Business, Edmonton, Alberta, 30 March 2009.

Kregel, Jan. “Minksy’s Cushion of Safety: Systemic Risk and the Crisis in the US Subprime Market.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Public Policy Brief No. 93. 2008

Minksy, Hyman P. “The Financial Instability Hypothesis.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 74. May 1992

Minsky, Hyman P. Charles J. Whalen. “Economic Insecurity and the Institutional Prerequisites for Successful Capitalism.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 165. May 1996

Nersisyan, Yeva. Randall Wray. “The Global Financial Crisis and the Shift into Shadow Banking.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 587. Feb 2010

Sheard, Paul. “Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not “Lend Out” Reserves.” Standard & Poor’s Working Paper, Aug 2013.

Whalen, Charles J. “The US Credit Crunch of 2007.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Public Policy Brief No. 92. 2007

Wray, Randall. “ The Financial Crisis Viewed from the Perspective of the “Social Costs” Theory.” The Levy Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 662. March 2011

Wray, Randall. “Improving Governance of the Government Safety Net in Financial Crisis.” The Levy Institute of Bard College Working Paper, April 2012.

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...