Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

September 2025 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Category Archives: MMP

BLOG #39 DISAGREEMENTS AMONG REASONABLE PEOPLE: RESPONSE TO MMT FOR AUSTRIANS #3

This week we continued our (unplanned) extension of commentary on Austrian economics. The post was featured on the home page of NEP as well as on the MMP. A large number of comments were provided, although few questions or comments that really needed response. There is no doubt that Austrian economics always provokes response—by lovers and haters. There is almost no in-between.

Posted in MMP

Blog 39: MMT for Austrians: Disagreements Among Reasonable People

My piece last week on MMT for Austrians set off a bit of a flurry of comments here and across the web, aided and abetted by commentary on the MMT event in Italy. Several followers of NEP have asked us to respond to some of the critiques made against MMT. I think that a long response is called-for, something we will put on both NEP and MMP as a blog. I’m ignoring the various Austrian comments over at Naked Capitalist—as my colleague Bill Black already offered thoughts. Besides, most of the commentary there is not substantial enough to require a response— given the constraints imposed on commentary on blogs, there’s not a whole lot there to respond to even in the posts by “reasonable” people.

I’m instead going to (mostly) respond to a series of comments made by reporter John Carney. I want to be clear here. This is not because Carney has made the most outrageous statements, but precisely the opposite: he has provided the most thoughtful reactions. And Carney understands MMT; indeed, he accepts much of the exposition. Further, as Carney is a reporter, he is not wont to making undocumented claims. Reporters know how to do “fact checking” and are held to much higher standards than are bloggers who hide their names and thus are free to make any outlandish claim they want. I presume that when Carney writes articles for CNBC the standards are higher than when he writes for his own blog at CNBC. Still, as a reporter his reputation and credibility would be severely damaged if he were to make unsubstantiated claims—so I presume he has fact checked his claims.

I’m going to rely on his “published” (that is to say, posted on internet sites, mostly his own) comments, plus a tweet or two (whatever that is).

There are three main themes. First, there is a reinterpretation of what we call sectoral balances, with a restatement and claimed correction to the MMT approach. Second, there is a claim that MMT does not account for corruption in government. And finally his main critique concerns the role of government—what should government do. There is something approaching a blanket claim that government can only impose economic costs—its positive contribution approaches zero. Hence, he appears to reject my whole premise that while we can agree on MMT as descriptive, reasonable people can disagree on the “public purpose”—what government ought to do.

For Carney there is no such thing as a public purpose, and hence no positive role for government to play. Reasonable people cannot agree to disagree on the public purpose because the concept is rejected.

Let me repeat: I am using Carney’s posts because I think they are the most cogent critiques the Austrians have to offer.

If we cannot effectively defend the MMT position against Carney’s critiques, then—as he claims—we at NEP “are doing something else that may be interesting but it isn’t economics. It isn’t a new economic perspective or heterodox economics or any kind of economics at all.”

That is quite a claim for a reporter to make—we at NEP do not do any kind of economics at all. Let’s see if he’s got his facts checked.

Theme One. From a Tweet: John Carney@carney: “Blows my mind when MMT people say that “accounting identities” prove that people can’t save without gov’t or for[eign] sect[or] running a deficit.”

Moi? Said people? Can’t save? Without government or foreign deficit? Really? We said that?

No John, we never said that. If any true MMTer ever said that it was in some special context. Here is what we actually say.

From MMP Blog #2: Inside wealth vs outside wealth. It is often useful to distinguish among types of sectors in the economy. The most basic distinction is between the public sector (including all levels of government) and the private sector (including households and firms). If we were to take all of the privately-issued financial assets and liabilities, it is a matter of logic that the sum of financial assets must equal the sum of financial liabilities. In other words, net financial wealth would have to be zero if we consider only private sector IOUs. This is sometimes called “inside wealth” because it is “inside” the private sector. In order for the private sector to accumulate net financial wealth, it must be in the form of “outside wealth”, that is, financial claims on another sector. Given our basic division between the public sector and the private sector, the outside financial wealth takes the form of government IOUs. The private sector holds government currency (including coins and paper currency) as well as the full range of government bonds (short term bills, longer maturity bonds) as net financial assets, a portion of its positive net wealth…..We can formulate a resulting “dilemma”: in our two sector model it is impossible for both the public sector and the private sector to run surpluses. And if the public sector were to run surpluses, by identity the private sector would have to run deficits. If the public sector were to run sufficient surpluses to retire all its outstanding debt, by identity the private sector would run equivalent deficits, running down its net financial wealth until it reached zero.

OK, if you read no further than this, it might seem to lend a tiny bit of support to Carney’s claim. Note however the words used are “private sector”, not “people”. So if one has a problem with the logic of this passage, I do not know what the heck it is: Two sectors. One can spend less than ones income only if another spends more. Surely any Austrian can understand this? Indeed John, later, seems to state exactly this:

Carney: The only thing that can make private-sector net savings possible is government spending. If the government spends more than it takes in taxes, the private sector can earn more than it spends. Remember, if everyone pays less than they earn, some outsider must be paying more than he earns. The government is basically filling in the role of the family who constantly needs babysitting—using up those saved hours and, therefore, providing a chance for the shut-in Park Slope parents to save even more hours. Once you wrap your head around that, it seems easy to understand what those MMT people are talking about when they say the government must run a deficit in order for the private sector to net save. But it’s also easy to mistake this fact for a number of similar but false statements.

Well, except for putting it in babysitter terms, John seems to argue exactly what I said above, written in Blog 2 early last summer.

So let us now go further. Let us separate “people” from “firms”, the sum of which is “private sector”. Are MMTers confused on how to do a simple division by the number two? Yes, John thinks we are incapable of such math. And to be fair to John, there is a whole website, called MMR, devoted to this supposed confusion on the part of MMT. I’ll come back to the MMR confusion in a second.

Here is Carney’s claim:

Carney: The recent blogosphere kerfuffle about saving arose in part because MMT embraces the sector financial balances model (SFB), which features the consolidation of household and corporate sectors as a unified private sector. The model treats financial claims on corporations as negative financial assets for corporations, so the consolidated result is that household saving deployed in such financial assets makes a zero net contribution to private sector saving after counterparty corporate netting….

First let’s see what I actually wrote last summer. John, here it is, you can read it for yourself (I’ve done your fact checking for you!):

MMP Blog #4: Deficits in one sector create the surpluses of another. Earlier we showed that the deficits of one sector are by identity equal to the sum of the surplus balances of the other sector(s). If we divide the economy into three sectors (domestic private sector, domestic government sector, and foreign sector), then if one sector runs a deficit at least one other must run a surplus. Just as in the case of our analysis of individual balances, it “takes two to tango” in the sense that one sector cannot run a deficit if no other sector will run a surplus. Equivalently, we can say that one sector cannot issue debt if no other sector is willing to accumulate the debt instruments. Of course, much of the debt issued within a sector will be held by others in the same sector. For example, if we look at the finances of the private domestic sector we will find that most business debt is held by domestic firms and households. In the terminology we introduced earlier, this is “inside debt” of those firms and households that run budget deficits, held as “inside wealth” by those households and firms that run budget surpluses. However, if the domestic private sector taken as a whole spends more than its income, it must issue “outside debt” held as “outside wealth” by at least one of the other two sectors (domestic government sector and foreign sector).

So, can Wray do division by two without confusion? Looks like he can. Even with a government budget that is balanced (and a foreign sector balance) it is possible for households to net save!

Wow!

And it is possible for Carney to save while Wray deficit spends—even though we are in the same household sector! In other words, even the household sector can be balanced and Carney—one of those households—can net save!

So, even if firms taken as a whole are balanced, and the government is balanced, and the foreign sector is balanced, one household can net save while another deficit spends! (Note we can subdivide the private sector as many times as we want and still derive similar results.)

And if John thinks that I just discovered these ideas last summer (maybe after reading the “brilliant” analysis by JKH—see below), he can look at my 1998 book, Understanding Modern Money (to my knowledge, the first time “modern money” was used to describe the MMT approach), Chapter 4, page 82 for almost exactly the same explanation—“To simplify we can assume that it is the household sector which saves and the business sector that invests; the net (inside) indebtedness of the business sector is exactly offset by the net (inside) financial wealth of the household sector. It is frequently the case that the household sector wishes to save more than the business sector wishes to invest.” And so on and so on and so on.

We didn’t even need the MMR blogsite! MMTers had it right all along!

And we really don’t even need Carney’s babysitter model, where he tries to correct MMTers with the following explanation:

Carney: The way Modern Monetary Theory folks talk about the economy leads to a lot of confusion. The best example is the assertion that the private sector cannot “net save” unless the government runs a budget deficit. This annoys and confuses people because it seems to be an assertion that people cannot save money unless the government is running a deficit. If that was what MMT was claiming, it would be nonsense. You and I are perfectly capable of saving regardless of how the government’s spending and revenues balance out

John claims MMT “seems” to say “people” cannot “save money”? Why would it “seem” such? MMT seems to me to say exactly the opposite of that? If John is “annoyed” I guess it is because he is not bothering to read what we actually write?

Now, John, if you want to say that you are a much better writer than me, fine. Go for it. Maybe what I write is beyond the grasp of the typical MMR blogger. I can remember when many people claimed that a certain MMR blogger was a much better writer than anyone at NEP and thus much better able to explain MMT—(only to find later that he rejects most of MMT and misunderstands much of it. Another matter entirely, admittedly. Sorry for the sidetrack.).

And if Carney and MMR were correct about the three balances, then that means Wynne Godley has to be wrong. I worked with Wynne and unlike the MMR folks I published with him (we were the first, ever, to warn of the coming global financial collapse, beginning in 1998). And I taught him MMT. He began to write a “government-centered” textbook, beginning with “taxes drive money” from Chapter One. Unfortunately, he did not live to see that book come to fruition, but he did incorporate much of the ideas into his analysis. And all of us MMTers owe a great debt of gratitude to Wynne for helping us to understand the three balances.

Carney: The problem here is that the correct definition of saving precisely specifies the passive act of not spending on consumer goods. It does not specify how the proceeds of such saving should be used, whether to acquire real or financial assets. Saving is described in proper accounting terms as funds sourced from income by virtue of being saved from income. The eventual deployment of that source of funds is described properly as a use of funds — whether such deployment and use occurs in the form of a bank deposit, a bond, a stock, newly produced residential real estate, or newly produced plant and equipment. The deployment or use of funds is separate from the act of saving itself. In summary, the consolidated private sector account obscures, not only the view of saving as it materializes within a given accounting period in bifurcated fashion across household and corporate sectors separately, but also the view of total private sector saving as it is projected fully into the household balance sheet, when captured as a cumulative measure over a sequence of such accounting periods. As a result, the consolidated private sector presentation within the sector financial balances model obscures the measurement of the core component of saving.

So, MMT does not get into what the savings are used for? Let us see what I wrote:

MMP BLOG #21: GOVERNMENT BUDGET DEFICITS AND THE “TWO-STEP” PROCESS OF SAVING. … as J.M. Keynes argued, saving is actually a two-step process: given income, how much will be saved; and then given saving, in what form will it be held…. How can we be sure that the budget deficit that generates accumulation of claims on government will be consistent with portfolio preferences, even if the final saving position of the nongovernment sector is consistent with saving desires? The answer is that interest rates (and thus asset prices) adjust to ensure that the nongovernment sector is happy to hold its saving in the existing set of assets.

{Now there are a lot of different definitions of the term “saving”. I actually wrote a journal article on that (it is short and not too wonky: “What is Saving, and Who Gets the Credit (Blame)?”, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 26, no.1, March 1992, pp. 256-262). To briefly summarize, at NEP we prefer to use the Godley sectoral balance approach, where he defined private sector saving as “net accumulation of financial assets” (NAFA), using the flow of funds data. Typically economists use the GDP equals national income equation where saving is defined as a residual: the net income received but not consumed (I’ll use it below in discussing the MMR approach). In theory these would lead to approximately the same result; in practice they do not because the NIPA accounts include imputed values. Godley preferred the flow of funds data but even they had to be carefully adjusted to ensure that every spending flow is actually financed and actually “goes somewhere” (ensuring “stock-flow consistency”). That is all quite wonky. My bigger point is that we can come up with alternative definitions of saving that would include unrealized capital gains as real and financial assets appreciate in value. Some want to include accumulation of real production—say, a farmer who produces corn for his family’s own consumption, who “saves” by putting away seed corn for future planting. All that is fine but as it does not have a financial counterpart it is not included in either the NAFA or NIPA definitions usually used in MMT. I’ll come back to this later. That should be clear in the quote above, which is discussing receipt of income and then a decision about how to save a portion of it so it has to be NAFA or NIPA saving, and not “real” saving of seed corn.}

Let’s get back to Carney’s complaints and “corrections” of MMT theory. Carney wants to go a bit further, moving on to causal relations among the balances to correct supposed MMT errors. Here is his critique:

Carney: Also, it’s simply not true that government deficits result from the private sector’s desire to net-save. Deficits can “accommodate” an aggregate demand in the private sector to save more than it earns, but they don’t result from that demand. Deficits result from votes by politicians interacting with the real economy. There’s no “to the penny” causal relationship.

Oh, really? And so Greece and Ireland are imposing Austrian Austerity and finding that deficits remain. Now why is that? Here is what I wrote (hint, you do not even need to read beyond the title of my post to get the drift of the argument):

MMP Blog #5: Government Budget Deficits are Largely Nondiscretionary: the Case of the Great Recession of 2007

In previous blogs we have examined the three balances identity and established that the sum of deficits and surpluses across the three sectors (domestic private, government, and foreign) must be zero. We have also attempted to say something about causation because it is not enough to simply lay out identities. We have argued that while household income largely determines spending at the individual level, at the level of the economy as a whole it is best to reverse that causation: spending determines income. Individual households can certainly decide to spend less in order to save more. But if all households were to try to spend less, this would reduce aggregate consumption and thus national income. Firms would reduce output, thus, would lay-off workers, cut the wage bill, and thereby lower household income. This is Keynes’s well-known “paradox of thrift”—trying to save more by cutting consumption will not increase saving…. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC) social spending by government (for example, on unemployment compensations) has risen while tax revenues have collapsed. The deficit has grown rapidly leading to widespread fears of eventual insolvency or bankruptcy….. The implication of growing deficits has been attempts to cut spending (and perhaps to increase taxes) to reduce deficits. The national conversation (in the US, the UK, and Greece, for example) presumes that government budget deficits are discretionary. If only the government were to try hard enough, it could slash its deficit. As I have argued in previous blogs (particularly in responses to questions), however, anyone who proposes to cut government deficits must be prepared to project impacts on the other balances (private and foreign) because by identity the budget deficit cannot be reduced unless the private sector surplus or the foreign surplus (flip side to the domestic current account deficit) is reduced. In this blog, let us look at the rise of the US government budget deficit since the GFC hit. We will ask whether the deficit has been, and might be, under discretionary control—if not then that raises questions about the attempts by deficit hysterians to reduce deficits.

I’m not going to repeat the whole argument here. Carney’s view seems to be that Congress voted to raise the deficit and that is why it exploded. Nonsense. As I show in that blog (that came out of an academic paper at www.levy.org) and as many of us at NEP have demonstrated, most of the increase to the US budget deficit was due to collapse of tax revenue—and most of that was unrelated to the Bush tax cuts. There were no Congressional votes to increase the deficit to a trillion dollars a year. There was a relatively small fiscal stimulus package that petered out over two years–$400 billion each. Deficits remain two years later and are orders of magnitude larger than the Congressionally-mandated stimulus package plus tax cuts. Where is the legislation to pump up deficits?

John, please list the changes to public law and the impacts of each on deficits; total the results and you will not get close to the expansion of budget deficits. And note that most of the offsetting impact of the rise to government deficits was in the domestic private sector—not on the foreign sector. In other words, the growing government deficits were mostly offset by growing private surpluses.

Haven’t Americans tried to “net save” more as a result of the crisis? Didn’t they cut back on shopping? Or is it “just my imagination running away with me” (as the Stones might say) that makes me perceive slower sales and ramped up layoffs? Did 10 million workers suddenly decide to take extended vacations? Or did they lose their jobs due to a rotten economy that encouraged consumers to cut back spending, which lowered GDP, which lowered national income and tax receipts, which caused government deficits to balloon?

On Carney’s reference to “to the penny causal relation”, that is not what MMTers have argued. Rather, Warren Mosler has argued that in a two sector model, the government sector deficit equals the nongovernment surplus “to the penny”; if we have three sectors then the government sector deficit equals the surplus that represents the sum of the foreign and domestic private sector balances. The causation is more complicated, as we have always argued. Don’t believe me? Ok here is what I argued throughout the MMP: it takes “two to tango”, so causation is complex:

MMP Blog #4: Because the initiating cause of a budget deficit is a desire to spend more than income, the causation mostly goes from deficits to surpluses and from debt to net financial wealth. While we recognize that no sector can run a deficit unless another wants to run a surplus, this is not usually a problem because there is a propensity to net save financial assets. That is to say, there is a desire to accumulate financial wealth—which by definition is somebody’s liability.

MMP Blog #20: Since tax revenues (and some government spending) are endogenously determined by the performance of the economy, the fiscal stance is at least partially determined endogenously; by the same token, the actual balance achieved by the nongovernment sector is endogenously determined by income and saving propensities. By accounting identity it is not possible for the nongovernment’s balance to differ from the government’s balance (with the sign reversed—one has a deficit and the other a surplus); this also means it is impossible for the aggregate saving of the nongovernment sector to be less than (or greater than) the budget deficit.

MMP Blog #4: Deficits -> savings and debts -> wealth. We have established in our previous blogs that the deficits of one sector must equal the surpluses of (at least) one of the other sectors. We have also established that the debts of one sector must equal the financial wealth of (at least) one of the other sectors. So far, this all follows from the principles of macro accounting. However, the economist wishes to say more than this, for like all scientists, economists are interested in causation. Economics is a social science, that is, the science of extraordinarily complex social systems in which causation is never simple because economic phenomena are subject to interdependence, hysteresis, cumulative causation, and so on. Still, we can say something about causal relationships among the flows and stocks that we have been discussing in the previous blogs…. If a household or firm decides to spend more than its income (running a budget deficit), it can issue liabilities to finance purchases. These liabilities will be accumulated as net financial wealth by another household, firm, or government that is saving (running a budget surplus). Of course, for this net financial wealth accumulation to take place, we must have one household or firm willing to deficit spend, and another household, firm, or government willing to accumulate wealth in the form of the liabilities of that deficit spender. We can say that “it takes two to tango”…. We can suppose there is a propensity (or desire) to accumulate net financial wealth. This does not mean that every individual firm or household will be able to issue debt so that it can deficit spend, but it does ensure that many firms and households will find willing holders of their debt. And in the case of a sovereign government, there is a special power—the ability to tax–that virtually guarantees that households and firms will want to accumulate the government’s debt…

The causation is difficult. It takes at least two to tango—a deficit spender and a willing saver to accumulate claims on the spender. We can summarize it as: at the aggregate level, spending determines income. But government deficits are largely nondiscretionary, to some extent they “fill the gap” left by collapsing private sector spending as government spending and taxing are largely countercyclical. The other side of the collapsing private spending is the desire by the private sector to repay debt and accumulate saving.

Let’s move to another topic Carney raises regarding this issue.

Carney: This raises an interesting question: should we enable the private sector to net save? There’s a good argument that we shouldn’t use government for this purpose. A private sector that doesn’t have recourse to government savings accounts would likely invest more.

Hold on there. If government spending and taxing are in any way tied to economic performance there is no intentional “enabling” required—the budget outcome will be countercyclical (deficit in bust, moving toward surplus in boom). Now if what Carney wants is a fixed government spending (say, $100 per year) and a fixed head tax ($1 per capita per year on each of the 100 inhabitants) then net spending by government will be zero so long as the inhabitants can actually pay their tax. It is far more likely that some will not be able to do so on a continuous basis, so the government will incur a deficit, and some taxpayers will lose their heads (penalty for not paying the head tax).

Carney’s final statement that in the absence of a government deficit, private saving would lead to more investment just makes no sense. Assume no government and no foreign sector. Investment creates saving in financial terms. Investment and Saving cannot be unequal. Add government that runs a deficit, then investment plus the deficit equals saving. Add the foreign sector and saving will equal the sum of investment plus net exports and plus the government deficit. This is not an either/or thing. It is an identity:

One Sector: I = S

Two Sectors: I + Def = S

Three Sectors: I + Def + NX = S

It is first day of economics 101. And there has been a long academic tradition since Keynes’s General Theory to establish the causation. In the one sector model, the causation must run from investment to saving. There is no possibility of having more (or less) saving than investment, and while we might like to save more, we cannot do so unless investment is higher (so that income is higher, so that we can take that first step to save more—then we take the second step regarding how to save). This is related to the paradox of thrift (go here for more).

Carney has adopted the amusing (nay, hysterical) and confused exposition over at MMR which rewrites the one sector model as:

0 = 0 so now add S to both sides

0 + S = 0 + S now add I to both sides and subtract 0 from both sides

I + S = I + S now subtract I from both sides

S = I – I + S now regroup

S = I + (S-I)

Here is what the MMR folks claim about it:

“Hence, our focus on S=I+(S-I) with the emphasis on the idea that “the backbone of private sector equity is I, not Net Financial Assets.” The idea is not novel, but simply clarifies the understanding of the private sector component.”

The equation is attributed to the “brilliant” analysis of some JKH—who is roundly praised by all those at MMR for coming up with the smoking gun against MMT and Godley’s sectoral balance approach.

This is the fundamental MMR equation that proves MMT wrong? The thing in parenthesis is excess or “net” saving. It is supposed to be eye-popping and revelatory, indeed, revolutionary in the deep meaning it exposes. It says that household saving is equal to investment plus the excess of saving over investment!

So a couple of hundred years of economics, let alone MMT’s two decades of work, is completely overthrown: saving exceeds investment! By the amount that saving exceeds investment. But why stop there? Let’s introduce government.

G + S = G + I + (S-I) now subtract G from both sides:

S = G + I + (S-G-I)

Saving exceeds government spending plus investment by the excess of saving over the sum of government spending and investment spending!

And let’s not stop there either: add infinity to both sides:

S + infinity = G + I +infinity + (S-G-I) now subtract infinity and we get

S = G + I + infinity + (S-G-I-infinity)

So saving is bigger than government spending plus investment plus infinity. And as we all know, infinity is a very big number. MMT is off by an order of infinity. My mind is blown, too. Since all the other variables are vanishingly small compared to infinity the equation actually says that saving exceeds infinity by the amount that saving exceeds infinity.

Take that plus four bucks to Starbucks and you’ve saved enough to buy a Latte.

Forty years ago “people” (purposely vague term, here, to protect the not so innocent) had to take mind-altering chemicals to reach such mind-boggling conclusions. For those who do not remember those episodes (either from imbibing excessively or from being too young to have been there during the Timothy Leary days) just watch the original Woodstock movie and pay particular attention to the speeches by Arlo Guthrie and John Sebastian.

Mind-blowing stuff.

Oh, and since we just celebrated the anniversary of what was perhaps the greatest athletic performance of all time—Wilt Chamberlain’s 100 point NBA game—I might mention that I’m taller than Wilt. By how much?, you ask. By the excess of my height over his, of course.

Ok that was a bit of fun at their expense. I admit that I cannot figure out what they think they are demonstrating with the self-described “brilliant” equation.

So far as I can tell, all the MMR discussion then centers around two claims. First, that it might be perfectly OK for the domestic private business sector to run deficits (net saving for it is negative) while the domestic private household sector runs surpluses, accumulating claims on that business sector.

So far, so good. Not at all inconsistent with what I argued on the MMP blog or in my 1998 book as demonstrated above. All are inside financial claims, and all net to zero. But lots of “real” activity could have resulted—that raises productive capacity and so on. (MMRs then provide loads of odes to entrepreneurial spirit and the like. Good. I’m down with them on that.)

Ok fine. But note that if the household sector continually ran deficits against the business sector (even with the private sector in balance) we could still get into trouble—and get a Minsky-type debt deflation simply because households cannot service their debts to firms. And also note it does no good to go the other way: what if firms went increasingly into debt against the household sector? Yes, they could get into trouble if gross income flows were not enough to service debts.

But MMRers ignore that as they jump to the conclusion that it is perfectly fine if the business sector’s deficit exceeds the household sector’s surplus—so the private sector taken as a whole is running a deficit.

Now, that is impossible in the one sector model (I=S). They’ve pulled a rabbit out of a hat and slipped in a second sector. Say it is the foreign sector. In that case, we’ve got a positive capital account (net exports are negative) and the proper equation is not the one they write, but rather S = I + (-NX), as net exports are negative, or S = I –NX. What this means is that foreigners are accumulating claims on the domestic private sector. Or, the domestic private sector is getting deeper in debt—to foreigners.

Is that always bad? Of course not. But if it happens year after year after year, should we be concerned? Perhaps. We might not be able to service the ever-growing debt of firms. And they might claim some of our real output.

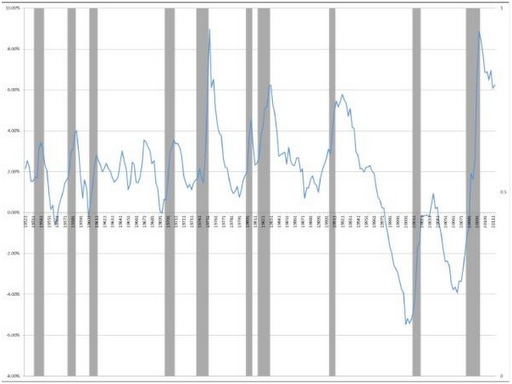

The other possibility is that the second sector is government—with government accumulating claims on the private sector. Always bad? Not necessarily. But when it continues trend-like, “history shows”–as Greenspan used to love to say–it is followed by a deep downturn (6 out of 7 times in the US continued federal government budget surpluses were followed by a depression; the seventh by the GFC). And even if we just look at tightening budgets—not necessarily full-on budget surpluses—recessions almost always follow. In the following picture the blue line shows the private sector balance—and as its surplus (or net saving) declines we usually see a recession (shaded area) soon after. In other words, empirically it certainly does look like reduction of net saving by the private sector is a pretty good indicator of a coming downturn—so this is not normally a good thing after all.

Second claim. The MMR people immediately moved on to “real saving” with some farmer whose cow somehow morphs into 10 cows, with the extra 9 cows “saving” that results without any deficits at all. (I take it that they don’t know much about animal husbandry.) Anyway, let us pretend that a cow can give birth to 9–count ‘em, nine!–calves and has got enough teats to keep them alive.

What does that have to do with nominal saving and nominal investment and hence the equations we’ve been going through? Who the heck knows? I think we need some of those mind-altering chemicals or math equations to get our brains around the “brilliance” of the analysis.

OK. Real stuff, real production, real saving—we’ve switched our definition of saving again. The claim is that MMR is more “real world” while MMT is somewhere out in the ether of theory land. Actually, I always allowed for “real saving”—as in a farmer who plants his own seeds, harvests them and saves some for next year. But note that one of the “Ms” in MMT (and presumably MMR) denotes “money” and hence focuses on the monetary system. That is not because we fail to recognize that there is “real stuff” and “real saving” but because we did not see any need to correct “Ricardian” economics that already deals with all that. Our complaint was that mainstream economics has got money all wrong.

{Apparently the R in MMR stands for “realism” or some such adjective—as in cows with 9 teats is more “realistic” than the cows I grew up with that had a mere four—occasionally and exceptionally five or six but that is no match for “modern money realism” that has cows with 9 teats (and presumably several udders). Perhaps a bit of instruction for our MMR buddies about “the birds and the bees” might be necessary, because you see, cows don’t replicate without bulls—so even if you got lucky and your cow had a male calf the first time around, to get more cows, that male would have to grow up and mate with his mom—which would lead to all of his buddies calling him an unkind word that begins with “M” and ends with “R”, and it is not “MMR” that they would call him. So aside from the nine calves and nine teats we’ve got a bit of a problem explaining where the bulls came from to make the “real stuff” that is the subject of MMR economics.}

Are the MMTers confused on this? I had several sections in the MMP to address the real junk. Let me see what I said, as Carney and the MMRs seem to have overlooked it.

Here is Blog 2’s discussion of real assets: A note on nonfinancial wealth (real assets). One’s financial asset is necessarily offset by another’s financial liability. In the aggregate, net financial wealth must equal zero. However, real assets represent one’s wealth that is not offset by another’s liability, hence, at the aggregate level net wealth equals the value of real (nonfinancial) assets. To be clear, you might have purchased an automobile by going into debt. Your financial liability (your car loan) is offset by the financial asset held by the auto loan company. Since those net to zero, what remains is the value of the real asset—the car. In most of the discussion that follows we will be concerned with financial assets and liabilities, but will keep in the back of our minds that the value of real assets provides net wealth at both the individual level and at the aggregate level. Once we subtract all financial liabilities from total assets (real and financial) we are left with nonfinancial (real) assets, or aggregate net worth.

And, what do you know, there is an MMP with the title: Blog 17: Accounting for Real Versus Financial (or Nominal). I wonder if it might have discussed the real junk MMR is concerned with? Let us see.

Blog 17: The state’s monetary unit is a handy measuring device that we use to measure credits, debts, and something fairly esoteric we might call “value”. …We need a measuring unit that is appropriate to measuring heterogeneous things. We cannot use color, weight, length, density, and so on. For historical reasons I will not go into right now, we usually use the state’s money of account. Otherwise, we can only measure value in terms of the thing itself. For example it is fairly easy to measure the value of sugar in terms of sugar—sugar weight will work, and if the crystals are uniform we could actually count them out. Usually however we measure sugar by volume at least for kitchen purposes…. When I go to tally up all of my wealth I will include all the Dollar IOUs I hold against banks, the government, other financial institutions, friends and family and so on. That is my gross financial wealth…. Against that I count up all of my own IOUs—to banks, government, family and friends.

Now clearly I am not done. I’ve got a house and a car… Assume I’ve got some debt against them, as I took out a loan (issued my own IOU to the bank or auto finance company, etc). That is part of my financial IOUs included in the calculation above. But I’ve been paying for years and so the outstanding IOU is much less than the value of my car and home. I count the monetary value of the car and home and add that to my financial assets to get gross assets. Now exactly how I value the house and car is tricky and subject to accounting rules. But that is not important to understand the principle here. We take the total value of gross assets (financial plus real) and subtract the outstanding liabilities (usually financial, but there could be some real sugar IOUs) to get net wealth. That of course, will be comprised of real assets plus net financial wealth. So total net wealth will be greater than net financial wealth because I’ve got real assets (car, house). (I could have negative net financial wealth that is—hopefully—more than offset by positive real assets. Otherwise I am “underwater”.)

Most of the time in this primer we are focused on the monetary part of the economy—indeed on what Keynes called “monetary production” and Marx called M-C-M’) in which production begins with money, to produce a commodity for sale for “more money” (profits). We focus on that because that is basically what capitalism is all about and we are mostly concerned with how “modern money” works in a capitalist economy. (Note, however, that “taxes drive money” applies to earlier societies that were not capitalist.) Still even in capitalism it is obvious that not all production involves money in the beginning and not all is undertaken on the prospect of making profit. In about two hours I am going to fix dinner and wash dishes. I am not going to get paid, much less earn any profits. Now at least some of this “production” process does begin with money—I bought most of the ingredients for the cooking, and purchased both water and soap for washing. But part of the ingredients (especially my labor) will not be purchased. Is this kind of production important? Undoubtedly—even in a highly developed capitalist economy like the American it is hard to see how any of the monetary production could take place without all of the unpaid labor involved in “reproducing” the “labor power” (these are Marx’s terms—you can replace them with “supporting the family that supplies workers”). Domestic services, child rearing, recreation and relaxation, and so on are critical and mostly do not involve monetary transactions. We can—and sometimes do—put monetary values on them anyway. Not only is there a “flow” dimension in the form of daily dishwashing, but there is also a “stock” dimension—accumulation of the knowledge and skills our youngsters will need later (often called “human capital” by economists). That (growing) stock should be added to our “real assets” and hence to our total net wealth. Obviously, these things are very difficult to measure in Dollar terms.

So, does that make us remiss in not discussing “real” production and “real” accumulation? I cannot see how.

I could have put this in terms of 1 cow replicating into 10 cows through virgin births with ample numbers of teats and adequate self-produced hay to support the whole lot without money intervening at all. Humans have overseen such miraculous multiplications (and even more than this if you can count the Savior’s water into wine and bread into fish—if I’ve got the stories right for I must admit I slept through a lot of that instruction) for thousands of years before there even was a monetary economy. In other words, the nine teated cows that MMR trots out have nothing to do with money whatsoever, and hence the MM part of the MMR is not even called into play to explain the miracles as “realistic” but not “modern money”. Truth in labeling should truncate the MMR site to just “R” as its concern is not money, modern or otherwise. It is the “Real 9 Teated Cow and Immaculate Conception” theory of economics, or R9TCIC website.

Theme Two: MMT ignores corruption in government.

Carney: It’s a shame that a guy as brilliant as Wray doesn’t quite understand that the “public sphere” is nearly always code for private interests expressed through political power.

OK, but JKH is also called “brilliant” so I’m not sure if that is meant as a compliment or a diss. Does Wray recognize that private interests are expressed through political power? Does Wray ignore what has been going on in Washington as the Bush-Clinton-Bush-Obama administrations turned not only Washington but virtually our entire economy over to the banksters on Wall Street? Has NEP totally overlooked problems of corruption?

There aren’t many economists (and certainly none of the MMRs pseudo-economists) who’ve written more on the frauds perpetrated by Wall Street and the “revolving door” operated by all of these administrations that have essentially turned the Treasury as well as the White House staff over to financial interests. And this is not some new-found concern—I also wrote about fraud and the involvement of government officials during the S&L crisis. (Admission: I was far too skeptical of Bush, senior’s response—little did I know that a guy named Bill Black would play a major role in resolution of that crisis—helping to put 1000 crooks behind bars; compared to Clinton and Obama, Bush sr came out of that crisis looking relatively clean.).

And I do not know how Bill “Control Fraud” Black, one of the main contributors to NEP—who literally “wrote the book” on bank fraud, can be characterized as someone who does not understand that political interests get expressed through political power. Does Carney really believe we all have checked skepticism at the door when we advocate a positive role for public policy?

Truth be told, I’ve been disappointed and even horrified by much of the US federal government’s policy since the days of LBJ. I will admit to buying-in to JFK’s Camelot when I was a kid, and I can remember the exact instant when the closest neighbor to my one-room school house burst into the classroom to announce on the afternoon of November 22, 1963 that he had been shot (we had no telephone, or even running water; and our textbooks were gloriously out-of-date so that we did not need to worry about WWII and postwar developments—there were only 48 states to remember, 7 known planets to study, and 31 president’s names—up to Hoover–to commit to memory). While most of the class cheered (some of that was due to the following announcement that we’d be going home, but most of it was due to the politics of the little Rick Santorums I counted as school chums) my own world was shattered. My family was then “all the way with LBJ” until he ramped up the war against Viet Nam—and from that point on I was never confused about the influence of private interests over the public purpose. Come on, the next President was Tricky Dick, after all—who brought the war home to attack our nation’s youth. And it was downhill after that. At the time, I never thought I’d look back on Tricky Dick as—arguably–the most progressive president of the past half century. Shame on those who followed him.

Theme Three: There is no public purpose.

Carney’s claim goes much further—he rejects the notion of public purpose and asserts that government’s contribution to the economy approaches zero.

Carney: I suspect that most government spending is socially destructive and economically malfeasant, and nearly all discretionary government spending is thoroughly corrupt, this seems to bother them less. My “right size” of government is far smaller—almost vanishingly small—than theirs. (Here’s Randall Wray, on of the leading MMT academics, arguing that government should spend 30 percent of GDP! Saints preserve us!)

Ok, sounding a lot like Rick Santorum, Carney invokes religion to save us from those godless MMT Keynesians who advocate big government. Now, in truth I never argued government “should spend” 30% of GDP. My whole article was arguing that it makes no sense at all to focus on such ratios. Instead, I asked all of us to put on the table what each of us believes to be worthwhile activities of government. My overriding point was that we could have all of the progressive wet dream utopian programs and it would still amount to less than 30% of GDP. Hence, my whole argument was precisely the opposite of what Carney’s accusation proclaims—my summing up of expenditures was to demonstrate that we’d still be left with a relatively small government, certainly in comparison to the size of government of all other developed capitalist countries—even if we adopted the full progressive wish list. And my point was to lay-out what government actually spends for so that our Austrian friends could tell us exactly which programs would get cut.

Unfortunately, they respond only with handwaves—just like the anti-government Republican candidates who refuse to tell us what they will cut, on the certain recognition that their views have almost no overlap with the American public’s. Instead they argue for a “vanishing small” government without telling us what, if anything, they’d cut and what, if anything, they’d retain.

Carney: For the record I should say, I’m way more libertarian than the MMR guys. Maybe I’m Neo-MMR.

Again I want to be clear. Reasonable people can disagree—that was the main point of my “MMT for Austrians” piece. Libertarians want a much smaller government. I have no problem with that. Go ahead, put your extreme ideology on the table. List which programs you support and let us total them up. Tell what you are going to cut. Take the heat. You’ll be soundly rejected by the 99% of the population that can figure out whose side you are on.

But Carney seems to argue much more than that. His claim comes close to arguing that there is no role at all for government.

Carney: What Brooks gets and Wray misses, however, is that government spending priorities are economically damaging. When resources are moved “to the public sphere” they are utilized to realize political ends rather than “public” ends. That is, they are used to satisfy the demands of special interests who influence lawmakers and regulators. This gap in understanding is one of the things that has given rise to the post-Modern Monetary Theory movement of Modern Monetary Realism.

As an ideological statement, I have no problem with this. Reasonable people can disagree. It is Carney’s belief that government really cannot do anything positive. But he goes on, proclaiming this is fact, not ideology:

Carney: This is not ideology. These are conclusions from decades of investigating the way government operates. As you guys like to say in other contexts, we’ve done the work so you don’t have to. Read my brother’s book.

So, according to Carney, decades of investigations reveal that “government spending priorities are economically damaging”.

In my post on NEP I had detailed exactly what government spending is, across the major programs. There really are only three main areas of spending that are large enough to make much difference to the overall budget: defense, Medicare, and Social Security. So if we are talking about “priorities” we must be talking about these areas. In my piece, I had advocated substantial downsizing of the defense sector (which I do see as economically and politically and morally damaging)—so when Carney argues that I “miss” the fact that spending priorities are “damaging” he must be referring to Medicare and Social Security.

Does Carney really believe that crediting the bank account of some 90 year old widow so that she can afford to live a more-or-less dignified life on Social Security is “economically damaging”? What is the economic evidence for the claim? Does he mean incentives? Without Social Security, she’d be incentivized and available to work—maybe at Burger King? Or does he prefer the third world model—she would be sitting on a blanket and selling “Chiclets”—pieces of gum—and dumpster diving for scraps of food? He’d properly align the incentives by taking away her Social Security benefits? Please, Carney, tell us how Social Security benefits damage the economy and what you would put in their place.

What about the people with disabilities who also collect Social Security? I used to live in Mexico and can recall the “safety net” for the man with no legs who had to cross busy lanes of traffic each day to get to “his” spot where he begged for coins. That’s the “free market” solution to disabilities. Is this the future Carney sees for our citizens living with disabilities?

Or is it Medicare—medical care for our aged—that is “economically damaging”? In what ways? And what would be the preferred and less economically damaging alternative? Just ignore healthcare needs of the bottom 99% that cannot afford care? If that 90 year old widow breaks a leg, you think it would be less economically damaging to just let her lay in bed and waste away, rather than putting her in a cast so she can serve burgers as she mends? And if a program like Medicare is so damaging, why is it that health outcomes are better in almost all countries that have government-paid universal healthcare? And overall living standards are higher in most of them?

He goes on, apparently to soften the conclusion a tiny bit:

Carney: But because these are conclusions drawn from years of investigation and research, I don’t think it’s terrible that you find them implausible…. although I draw pragmatically libertarian lessons from the facts about public policy production, there are other possible lessons that decent people could arrive at. Even if government spending is as bad as I say it is, it may be necessary to accomplish other things that are absolutely required. For instance, the defense industry is a racket. But if we were invaded or under threat of invasion, I’d put up with letting the arms dealer loot us because that’s the only way to get enough guns to defend the country.

I wonder if Carney would carry this a bit further. Let us say for the sake of argument that every government project is subject to corruption. Carney’s willing to trade off some corruption for defense of the nation. Would he draw a pragmatically libertarian lesson that it is still better to have an interstate highway system in spite of the supposed inefficiencies of the “racket” of “looting” by road construction workers and firms?

How about clean water? Working sewers for flushing toilets? Police force? Public schools and universities? Government support for R&D that resulted in the 747, computers, the internet, vaccinations that have wiped out most of the worst childhood diseases?

Would he take a bit of inefficiency and public corruption as a tradeoff to have security in those areas?

In short, all of those things that separate life in the US and all other developed countries from the low living standards in the developing nations with the very small governments that Carney prefers? Or would he rather forgo all of that because there is some corruption?

Has Carney overlooked all the advantages of a government that recognizes and supports the notion of public purpose, in spite of all of its flaws? Is Carney only willing to overlook the obvious flaws of—say—a virtually unregulated financial system that—arguably–has in just four short years resulted in greater economic losses than the sum total of all government “inefficiencies” of the past few centuries?

I have never been in any country, anywhere, in which audiences do not readily recount horror stories about government corruption. I think these stories are mostly true. And, yet, most places I visit have tolerably good public infrastructure and services, paid for by “corrupt” government always in “cahoots” with a thoroughly corrupt criminal class in the private sector.

Carney would point his finger at government and prefer to downsize it—while leaving provision of services and infrastructure to a great deal of luck and hope that kleptocratic private sector crooks will be guided by invisible hands to operate in the public interest while making profits for the private interest.

Yet, for every Geithner shoveling public money to private sector banks, there are a dozen Blankfeins subverting the public purpose. Yes there is no doubt that there is a revolving door in every administration—all of the Clinton-Obama top dogs came from Wall Street and expect to go back with higher incomes since they’ll funnel Uncle Sam’s money to their once and future employers. Isn’t it a bit strange that Carney’s response is to downsize or virtually eliminate government, rather than going after the kleptocratic crooks that undermine public policy?

I’d prefer to point my finger at the crooks in both the private and public sectors, and then jail them. I do not support either kleptocrats or invisible hand waves that suppose private interest, alone, is enough.

But Reasonable People can Disagree. Can’t they?

Posted in MMP

Responses to Blog 38: Austrians: Love ‘Em, Hate ‘Em, Wish You Could Eat ‘Em

Ok: 32 comments and counting. Must be a record. Way too many to respond to. I guess we need another full blog. You either love them or you hate them. Apparently there’s no in-between. Also I note that reporter John Carney has picked up my MMT for Austrians blog and written several of his own ideologically-infused interpretations that have almost no earthly grounding.

Comments Off on Responses to Blog 38: Austrians: Love ‘Em, Hate ‘Em, Wish You Could Eat ‘Em

Posted in MMP, MMT, Modern Monetary Theory, modern money theory, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

MMP Blog 38: MMT for Austrians

In the past couple of weeks we turned to the question what should government do, and last week we discussed the concept of the public purpose.

Clearly, we want the economy to do a lot of things for us, and the non government sector(s)can accomplish much of that. Some of the non government provisioning is non-monetary—outside markets. For example, the unpaid work within the family.Much is provided from the “monetary production economy”—the part of the economy in which production begins with money in order to end up with more money. (Some readers will recognize the source of that—and we’ll have more to say in a few weeks.)

But while non monetary plus monetary production by the non government sector(s) can accomplish a lot, they cannot provide everything we want.

It can even be argued that as societies become richer and more developed (some even use the term “advanced” but that can be invidious) we develop “higher-order” needs and wants.

(I do not want to go into this here, but it could be argued that in moving from, say, a tribal society to a monetary capitalist society we will need much more provisioning from the center precisely because less will and can be done by kinship organizations. To put it simply, moving to a monetary economy inevitably puts more responsibility on the issuer of the money—the sovereign government.It is in a sense a two-pronged fork: monetary economies “advance”, creating more higher order wants and needs that can only be satisfied monetarily, and by the government that issues the money.)

If you look back at our discussion last week of recognized human rights it might be apparent that we need to look beyond the production within the household and the production by for-profit firms to ensure those rights. In other words, the“public purpose” may well expand.

In addition, if we take account of environmental sustainability considerations,the scope for the public purpose likely will expand. (Those familiar with the work of Karl Polanyi will recognize the relation to the argument about the“double movement”. Capitalist development creates environmental problems that require a public response.)

Arguably the most contentious debate between left and right is over the best way to achieve the public purpose. As I admitted last week, there are some who would go so far as to deny the concept altogether and perhaps even a greater number who would deny most of the listed human rights. But let us proceed with our discussion here taking it for granted that there is some recognized public purpose. The point of contention is over the best way to provide for it.

Conservatives tend to argue that the government’s scope should be very narrow, even given agreement on the public purpose. They believe that households and firms can provide for most economic needs and wants. Government is needed in narrowly confined areas—such as police and military. There is often reference to the benefits of “free markets” and to Adam Smith’s notion of the invisible hand. Tobe very brief, this is the idea that individuals pursuing their own self-interest are guided “as if” by an invisible hand to do what is actually in the interest of society as a whole. The guiding is done by the market, and more specifically by prices that act as signals. If more lawyers are needed, their salaries are bid up in the market and students react by switching to the study of law. You all get the picture. It is a very nice metaphor.

There are two problems with the story. First, it is not really Adam Smith’s view. Second,economic theory has pretty much destroyed any hope that real world markets could possibly work that way. And I am not talking about Keynesian or other critical economic theory—I’m talking about economists who desperately wanted to“prove” that the invisible hand works in the proffered manner.

Again, I’ll be brief but let’s look at these two problems before moving on to the topic of MMT for Austrians.

Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand

One of the greatest scholars of Adam Smith, Warren J. Samuels, recently published a book on the invisible hand metaphor. (Erasing the Invisible Hand: Essays on an Elusive and Misused Concept in Economics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. xxviii + 329 pp. $95 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-0-521-51725-6.) It was reviewed by Gavin Kennedy (here: EH.Net (February 2012). All EH.Net reviews ar earchived at http://www.eh.net/BookReview). Since hand waves about the invisible hand and references to Adam Smith as the father of the notion are so commonplace, I want to quote extensively from Kennedy’s review.

Quote: “Smith did not”coin” the phrase. It was prevalent in classical times from Aeschylus through to St Augustine, and later, in numerous seventeenth- and eighteenth-century theological texts, sermons, plays (Shakespeare), poems, and novels (Defoe, Walpole), and in political rhetoric (George Washington). … Adam Smith used it only twice as a metaphor in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)and Wealth of Nations (1776), and once in his History of Astronomy (1795,posthumous). After Smith, there was an absence of mentions of the invisible hand metaphor among economists to 1875 and near silence thereafter until it was rediscovered and re-invented into the “founding concept” of modern economics from the 1940s… Samuels discusses Adam Smith’s supposed use of the invisible hand in his political economy. … Samuels’ conclusions in Essay 10 are best summarized by his question: “what is left of the invisible hand” (p.293) and by his answer: “There is no invisible hand as that term is used in economics. Its continued use must at its base constitute an embarrassment. Almost all uses of the term add nothing to substantive knowledge”.”

Quote: “Smith used the metaphor of “an invisible hand” to”describe in a more striking and interesting manner” their particular objects: it was the absolute mutual dependence of the “unfeeling landlord” on his serfs, servants, and tenants (‘no food, no labour’), and their mutual dependence on him (‘no labour, no food’), which mutual dependence led him to share his crops with them, unintentionally benefiting humanity through the “propagation of the species” (Theory Moral Sentiments,1759, p. 185); and it was the insecurity felt by some, but not all, merchant traders, that led them to prefer to invest in “domestick industry” (mentioned four times), rather than risk the “foreign trade of consumption”(Wealth Of Nations, 1776, p. 456), also unintentionally benefiting society by adding to domestic revenue and employment. Smith’s use (History of Astronomy, 1795, p. 49) of the “invisible hand of Jupiter” simply states the pagan beliefs of Romans about their god, Jupiter, whom they believed (but never witnessed) cast his lightning bolts at humans. In all three cases, it is evident that for Smith the “invisible hand” does not exist; it is an imaginary figure of speech and an imagined pagan belief. We cannot see, but we can imagine; we may choose to believe or not to believe. The “invisible hand” “corresponds to nothing in reality,” it “contributes nothing to knowledge,” and is a “distraction and a diversion, (Samuels, p. 146).”

So what we actually see in Smith is use of the invisible hand to discuss the relation of the feudal lord to his peasants (obviously, this is pre-capitalism and hence pre-“market economy” as it is a relation based on visible force rather than the invisible hand of prices), in relation to his belief that there is a somewhat natural inclination to produce for domestic consumption, and finally to movement of heavenly bodies. None of these has anything to do with price signals and invisible hands leading to efficient allocations of scarce resources.

No wonder economists paid almost no attention to Smith’s notion of the invisible hand until after WWII!

Postwar Developments in General Equilibrium Theory

o be sure there had been an attempt from the 1870s to demonstrate the idea that markets would tend to generate a “general equilibrium”—even if it did not refer to Smith or the invisible hand.

Discussion of this topic can get quite difficult, but what conservative economists wanted to show it that “demand and supply” for all produced goods and services could be brought into equilibrium by flexible prices and wages. If every market is in equilibrium, where demand equals supply, we call that a general equilibrium.

I am simplifying but this is good enough for now. In any case, it turns out to be a very difficult thing to show and believe it or not requires higher mathematics. Indeed, it is so complex that proof of the existence of general equilibrium was not accomplished until the 1950s—some 80 years after the project began. And even then the results were extremely disappointing.

First, the conditions required to demonstrate existence of equilibrium (technically a vector of relative prices that eliminate excess demand in every market) require a very simple and unrealistic world. For our purposes it is relevant to note that the hypothesized world would never use money! (Students of economics also know it requires no time, no uncertainty, a Walrasian auctioneer, and so on. Essentially, you contract at birth for all transactions you will ever make over your entire life, with perfect certainty and no regrets.)

Second, it turned out that the equilibrium is neither unique nor stable. Indeed, it turns out that there are many equilibria, perhaps an infinite number, and we cannot say that any one is better than any other. And if we do not happen to be in equilibrium, market forces will not move us to one of the equilibria.

Pretty darned disappointing since the whole claim was that “free markets” would move us to equilibrium with prices signaling how best to allocate resources.

They won’t. At least we cannot demonstrate that they will.The “invisible hand” is completely impotent. Might as well have a dictator. Or a dictatorship of the proletariat. Or a coin toss. Or winner-take-all. Or any other method of trying to allocate resources. We cannot show that markets would do a better job.

Anyone who tells you that economics shows that the invisible hand “works” is a fool or a liar or confused. Plain and simple, rigorous economic theory shows no such thing.

(In 1926 Keynes wrote a great essay on “The End of Laissez Faire”; I won’t go through it in detail but what he argued is that no economist had ever accepted the notion that the free market “works”. He said that only political ideologues pushed that idea, an idea he thoroughly destroyed in his essay. However, in the last third of the essay he tried, and failed, to produce an alternative view. It took him ten years—until 1936—to create the alternative, what became The General Theory. It wasn’t until he formulated his theory of effective demand and addressed the “special properties of money” that he could counter the free market ideology.)

Now, why did I devote so much space to a discussion of the invisible hand? Because so many “free market marketeers” rely on the notion,and on the supposed authority of Adam Smith, to push their ideological agenda.

To be clear, the inability to demonstrate that an invisible hand “works” does not settle the issue. It does not in any way “prove” that “big government” is better than “small government”. It does not “prove” that the best way to ensure the public purpose is to rely on government rather than markets. And it does not demonstrate that we should adopt an expansive, progressive view of the public purpose. But it does make one highly skeptical of “invisible” hand waves about “free markets”.

Yet, it must be admitted that in truth, economics, alone,cannot answer those questions.

Let us now return to the topic at hand: can an Austrian adopt MMT?

MMT for Austrians

I am using Austrians as an example of those who prefer a narrow view of the public purpose and who believe that “free” markets can accomplish most of the public purpose. Hence, the role for the government should be quite limited. Obviously, Austrians are not the only conservatives who adopt these views. However, they provide a reasonably consistent and coherent alternative to both orthodox and heterodox approaches to economics.

(Some include Austrians within heterodoxy, and there are some affinities—on topics like time, expectations and uncertainty. While I recognize similarities on those dimensions, most of the rest of heterodoxy accepts elements of Keynesian, institutionalist and/or Marxist thought that are anathema to Austrians. Hence I put Austrians in their own camp. For the purposes of the discussion that follows, this is not really important.)

Austrian views on government are well-known. Further, Austrians are frequent commentators on MMT blogs, and many have asked whether Austrians can accept MMT.

I would assure Austrians that MMT is not just for advocates of big government. Indeed,I have always been surprised that some of the most vehement critics of MMT are some of the libertarians and Austrians.

Relatedly, often when there is an MMT blog, the comments are dominated by conspiracy theorists, haters of government, and goldbugs who are certain that MMT-ers ar eunited in their effort to ramp up government until it consumes the entire economy. Some Austrians agree on these critiques. This section will attempt to put those fears to rest.

First, on one level, MMT is a description of the way a sovereign currency works. Love it or hate it, our sovereign government spends by crediting bank accounts. Over the past 20 years, MMT has investigated, analyzed, and documented the sordid operational details. We can lecture for hours on the balance sheet manipulations involving the Treasury, the Fed, the primary security dealers, the special depositories, and the regular private banks every time the Treasury buys a notepad from OfficeMax. We did the work, so you our Austrian colleagues do not have to do it. And believe me, you do not want to do it. You can skip directly to the conclusion: “Yes, government spends by crediting bank accounts, taxes by debiting them, and sells bonds to provide an interest-earning substitute to low-earning reserves.”

A few libertarians and Austrians now get this, although instead of thanking us for a job well done, some of them immediately attack MMT for explaining how things work. Now, why would they do that? Because they fear that if we tell policymakers and the general public how things work, democratic processes will inevitably blow up the government’s budget as everyone demands more from government—that is for precisely the reason that Samuelson advocated that “old time religion, without which off we go to Zimbabwe land, with hyperinflation that destroys the currency.

Ok, understood.

But MMT-ers fear inflation, too. Indeed, “price stability” has always been one of the two key missions of UMKC’s Center for Full Employment and Price Stability (http://www.cfeps.org/).

(I note that my friend Edward Harrison has long pushed MMT at his own blog, http://www.creditwritedowns.com/ even as he vocally disagrees with many of us on the role of government. So there are exceptions who recognize that MMT is useful for economists of all persuasions.)

To be sure, many libertarians and Austrians believe that the only foolproof method for avoiding inflation is to go back to gold. Again, fine. But don’t criticize our labor “buffer stock” scheme for its political infeasibility! Going back to the gold standard is even less likely. (I’d place my bet on socialist sharing of undergarments as more likely than a return to gold.)

Anyway, we (also) do not want black helicopters flying around dropping bags of cash; and we (also) oppose government “pump-priming” demand stimulus—the libertarians and Austrians and even Milton Friedman are correct in their argument that this would generate inflation.

Come to think of it, MMTers have more in common with Austerians than with “military Keynesianism” that supposes that high enough spending on the defence sector will cause full employment to“trickle down”. Most MMTers believe we’d get intolerable inflation before the jobs trickle down to Harlem.

In any case it is true that there is a second level to MMT: we use our understanding of the way money works to bring rational analysis to government policy-making. Since involuntary default is, literally, impossible for a sovereign government, we quickly move beyond fears about government deficits and debt ratios and all the other nonsense that currently grips Washington.

Can we “afford” full employment? Yes. Can we “afford” Social Security? Yes. Can we “afford” to put wine in all the drinking fountains? Yes.

The problem IS NOT, CANNOT BE about affordability. It is about resources.

Unemployment is easy: by definition, someone who is unemployed is available to hire. So government can put them to work. (See the next blog series for a plan.)

Social Security is a little more difficult: can we move enough resources to the aged (plus their dependents, and people with disabilities) so that they can enjoy a comfortable, American-style, life? On all reasonable projections of demographics and US ability to produce, the answer is yes. The projectionscould turn out to be wrong. But if they do, affordability still will not be the problem—it will be a resource problem.

Finally, wine in drinking fountains? There probably is not enough fine wine, but we could probably fill all the drinking fountains with cheap French wine. If we run out, Missouri can fill the gap (for those who do not happen to live in the US Midwest, the big MO before prohibition was second only to NY in wine production.)

Again, it is a resource problem and if we convert the American and Canadian prairies to wine production we could even resolve that one.

Perhaps the most important policy pushed by most MMT-ers is the Job Guarantee/Employer of Last Resort proposal. This provides a federal-government funded job to anyone who wants to work, at a uniform, basic compensation (wages plus benefits).

Many of our libertarian/Austrian fellow travelers seem to hate this program, again for unfathomable reasons. I suspect that they have misinterpreted this to be some kind of Big Government/Big Brother program based on a weird combination of force plus welfare.

The claim is simultaneously that it “forces” everyone to work, and that it also pays everyone for not working.

Actually, it is a purely voluntary program, only for those who want to work. Those who will not work cannot participate.

Libertarians and Austrians ought to love it. It is not Big Brother. It is not even Big Government. The jobs do not have to be provided by government at all. No one has to take a job. It is consistent with, I think, the most cherished norms of freedom-loving libertarians and Austrians.

So to sum up:

1. MMT is consistent with any size of government. It can be a small libertarian government if desired. But it issues a sovereign floating currency. It supports the currency by imposing a tax payable in that currency.

2. Job Guarantee/Employer of Last Resort is also consistent with any size of government. If you want a big private sector and small government sector, keep taxes and government spending low. That frees up resources to be used by the big private sector. But you will need the JG/ELR to take up the labor resources the private sector cannot fully employ.

3. JG/ELR can be as decentralized as desired. I think there are massive incentive problems if you have federal government pay wages of for-profit firms. So I would have federal government pay the wages in the program but have the jobs actually created and managed by: not-for-profits, local government, maybe state government, maybe only as a final last resort the federal government. Argentina experimented with cooperatives and they looked to me to be highly successful.

4. The problem with a monetary economy (you can call it capitalism if you like) is that from inception imposition of taxes creates unemployment (those looking for money to pay taxes). We scale this up to our modern almost fully monetized economy (you need money just to eat, watch TV, play on cell phones, etc) and we get everyone looking for money (and not just to pay taxes). It is sheer folly to then force the private sector to solve the unemployment problem created by the government’s tax. The private sector alone will never (never has) provide full employment. ELR/JG is a logical and empirical necessity to support the private sector. It is a complement not a substitute for private sector employment.