By Michael Hudson

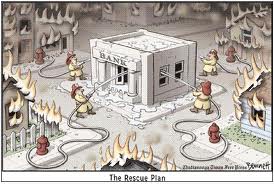

Financial crashes were well understood for a hundred years after they became a normal financial phenomenon in the mid-19th century. Much like the buildup of plaque deposits in human veins and arteries, an accumulation of debt gained momentum exponentially until the economy crashed, wiping out bad debts – along with savings on the other side of the balance sheet. Physical property remained intact, although much was transferred from debtors to creditors. But clearing away the debt overhead from the economy’s circulatory system freed it to resume its upswing. That was the positive role of crashes: They minimized the cost of debt service, bringing prices and income back in line with actual “real” costs of production. Debt claims were replaced by equity ownership. Housing prices were lower – and more affordable, being brought back in line with their actual rental value. Goods and services no longer had to incorporate the debt charges that the financial upswing had built into the system.

Financial crashes came suddenly. They often were triggered by a crop failure causing farmers to default, or “the autumnal drain” drew down bank liquidity when funds were needed to move the crops. Crashes often also revealed large financial fraud and “excesses.”

This was not really a “cycle.” It was a scallop-shaped a ratchet pattern: an ascending curve, ending in a vertical plunge. But popular terminology called it a cycle because the pattern was similar again and again, every eleven years or so. When loans by banks and debt claims by other creditors could not be paid, they were wiped out in a convulsion of bankruptcy.

Gradually, as the financial system became more “elastic,” each business recovery started from a larger debt overhead relative to output. The United States emerged from World War II relatively debt free. Downturns occurred, crashes wiped out debts and savings, but each recovery since 1945 has taken place with a higher debt overhead. Bank loans and bonds have replaced stocks, as more stocks have been retired in leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and buyback plans (to keep stock prices high and thus give more munificent rewards to managers via the stock options they give themselves) than are being issued to raise new equity capital.

But after the stock market’s dot.com crash of 2000 and the Federal Reserve flooding the U.S. economy with credit after 9/11, 2001, there was so much “free spending money” that many economists believed that the era of scientific money management had arrived and the financial cycle had ended. Growth could occur smoothly – with no over-optimism as to debt, no inability to pay, no proliferation of over-valuation or fraud. This was the era in which Alan Greenspan was applauded as Maestro for ostensibly creating a risk-free environment by removing government regulators from the financial oversight agencies.

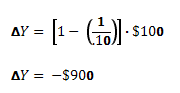

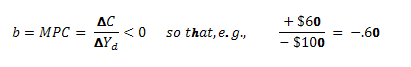

What has made the post-2008 crash most remarkable is not merely the delusion that the way to get rich is by debt leverage (unless you are a banker, that is). Most unique is the crash’s aftermath. This time around the bad debts have not been wiped off the books. There have indeed been the usual bankruptcies – but the bad lenders and speculators are being saved from loss by the government intervening to issue Treasury bonds to pay them off out of future tax revenues or new money creation. The Obama Administration’s Wall Street managers have kept the debt overhead in place – toxic mortgage debt, junk bonds, and most seriously, the novel web of collateralized debt obligations (CDO), credit default swaps (almost monopolized by A.I.G.) and kindred financial derivatives of a basically mathematical character that have developed in the 1990s and early 2000s.

These computerized casino cross-bets among the world’s leading financial institutions are the largest problem. Instead of this network of reciprocal claims being let go, they have been taken onto the government’s own balance sheet. This has occurred not only in the United States but even more disastrously in Ireland, shifting the obligation to pay – on what were basically gambles rather than loans – from the financial institutions that had lost on these bets (or simply held fraudulently inflated loans) onto the government (“taxpayers”). The government took over the mortgage lending guarantors Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (privatizing the profits, “socializing” the losses) for $5.3 trillion – almost as much as the entire national debt. The Treasury lent $700 billion under the Troubled Asset Relief Plan (TARP) to Wall Street’s largest banks and brokerage houses. The latter re-incorporated themselves as “banks” to get Federal Reserve handouts and access to the Fed’s $2 trillion in “cash for trash” swaps crediting Wall Street with Fed deposits for otherwise “illiquid” loans and securities (the euphemism for toxic, fraudulent or otherwise insolvent and unmarketable debt instruments) – at “cost” based on full mark-to-model fictitious valuations.

Altogether, the post-2008 crash saw some $13 trillion in such obligations transferred onto the government’s balance sheet from high finance, euphemized as “the private sector” as if it were the core economy itself, rather than its calcifying shell. Instead of losing on their bad bets, bad loans, toxic mortgages and outright fraudulent claims, the financial institutions cleaned up, at public expense. They collected enough to create a new century’s power elite to lord it over “taxpayers” in industry, agriculture and commerce who will be charged to pay off this debt.

If there was a silver lining to all this, it has been to demonstrate that if the Treasury and Federal Reserve can create $13 trillion of public obligations – money – electronically on computer keyboards, there really is no Social Security problem at all, no Medicare shortfall, no inability of the American government to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure. The bailout of Wall Street showed how central banks can create money, as Modern Money Theory (MMT) explains. But rather than explaining how this phenomenon worked, the bailout was rammed through Congress under emergency conditions. Bankers threatened economic Armageddon if the government did not create the credit to save them from taking losses.

Even more remarkable is the attempt to convince the population that new money and debt creation to bail out Wall Street – and vest a new century of financial billionaires at public subsidy – cannot be mobilized just as readily to save labor and industry in the “real” economy. The Republicans and Obama administration appointees held over from the Bush and Clinton administration have joined to conjure up scare stories that Social Security and Medicare debts cannot be paid, although the government can quickly and with little debate take responsibility for paying trillions of dollars of bipartisan Finance-Care for the rich and their heirs.

The result is a financial schizophrenia extending across the political spectrum from the Tea Party to Tim Geithner at the Treasury and Ben Bernanke at the Fed. It seems bizarre that the most reasonable understanding of why the 2008 bank crisis did not require a vast public subsidy for Wall Street occurred at Monday’s Republican presidential debate on June 13, by none other than Congressional Tea Party leader Michele Bachmann – who had boasted in a Wall Street Journal interview two days earlier, on Saturday, that she

voted against the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) “both times.” … She complains that no one bothered to ask about the constitutionality of these extraordinary interventions into the financial markets. “During a recent hearing I asked Secretary [Timothy] Geithner three times where the constitution authorized the Treasury’s actions [just [giving] the Treasury a $700 billion blank check], and his response was, ‘Well, Congress passed the law.’ …With TARP, the government blew through the Constitutional stop sign and decided ‘Whatever it takes, that’s what we’re going to do.’”

Clarifying her position regarding her willingness to see the banks fail, she explained:

I would have. People think when you have a, quote, ‘bank failure,’ that that is the end of the bank. And it isn’t necessarily. A normal way that the American free market system has worked is that we have a process of unwinding. It’s called bankruptcy. It doesn’t mean, necessarily, that the industry is eclipsed or that it’s gone. Often times, the phoenix rises out of the ashes. [1]

There were easily enough sound loans and assets in the banks to cover deposits insured by the FDIC – but not enough to pay their counterparties in the “casino capitalist” category of their transactions. This super-computerized financial horseracing is what the bailout was about, not bread-and-butter retail and business banking or insurance.

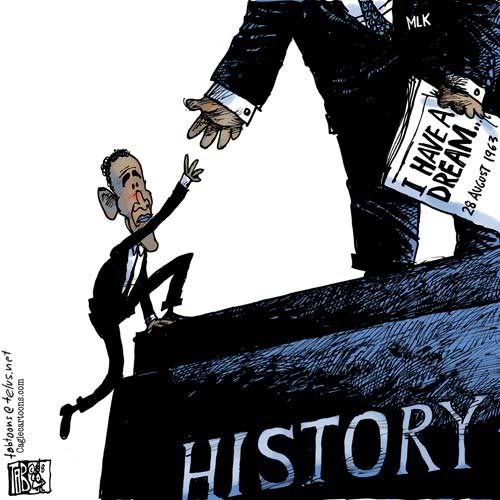

It all seems reminiscent of the 1968 presidential campaign. The economic discussion back then between Democrat Hubert Humphrey and Republican Richard Nixon was so tepid that it prompted journalist Eric Hoffer to ask why only a southern cracker, third-party candidate Alabama Governor George Wallace, was talking about the real issues. We seem to be in a similar state in preparation for the 2012 campaign, with junk economics on both sides.

Meanwhile, the economy is still suffering from the Obama administration’s failure to alleviate the debt overhead by seriously making banks write down junk mortgages to reflect actual market values and the capacity to pay. Foreclosures are still throwing homes onto the market, pushing real estate further into negative equity territory while wealth concentrates at the top of the economic pyramid. No wonder Republicans are able to shed crocodile tears for debtors and attack President Obama for representing Wall Street (as if this is not equally true of the Republicans). He is simply continuing the Bush Administration’s policies, not leading the change he had promised. So he has left the path open for Congresswoman Bachmann to highlight her opposition to the Bush-McCain-Obama-Paulson-Geithner giveaways.

The missed opportunity

When Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, the presidential campaign between Barack Obama and John McCain was peaking toward Election Day on November 4. Voters told pollsters that the economy was their main issue – their debts, soaring housing costs (“wealth creation” to real estate speculators and the banks getting rich off mortgage lending), stagnant wage levels and worsening workplace conditions. And in the wake of Lehman the main issue under popular debate was how much Wall Street’s crash would hurt the “real” economy. If large banks went under, would depositors still be safely insured? What about the course of normal business and employment?

Credit is seen as necessary; but what of credit derivatives, the financial sector’s arcane “small print”? How intrinsic are financial gambles on collateralized debt obligations (CDOs, “weapons of mass financial destruction” in Warren Buffett’s terminology) – not retail banking or even business banking and insurance, but financial bets on the economy’s zigzagging measures. Without casino capitalism, could industrial capitalism survive? Or had the superstructure become rotten and best left to “free markets” to wipe out in mutually offsetting bankruptcy claims?

Mr. Obama ran as the “candidate of change” from the Bush Administration’s war in Iraq and Afghanistan, its deregulatory excesses and giveaways to the pharmaceuticals industry and other monopolies and their Wall Street backers. Today it is clear that his promises for change were no more than campaign rhetoric, not intended to limit a continuation of the policies that most voters hoped to see changed. There even has been continuity of Bush Administration officials committed to promoting financial policies to keep the debts in place, enable banks to “earn their way out of debt” at the expense of consumers and businesses – and some $13 trillion in government bailouts and subsidy.

History is being written to depict the policy of saving the bankers rather than the economy as having been necessary – as if there were no alternative, that the vast giveaways to Wall Street were simply “pragmatic.” Financial beneficiaries claim that matters would be even worse today without these giveaways. It is as if we not only need the banks, we need to save them (and their stockholders) from losses, enabling them to pay and retain their immensely rich talent at the top with even bigger salaries, bonuses and stock options.

It is all junk economics – well-subsidized illogic, quite popular among fundraisers.

From the outset in 2009, the Obama Plan has been to re-inflate the Bubble Economy by providing yet more credit (that is, debt) to bid housing and commercial real estate prices back up to pre-crash levels, not to bring debts down to the economy’s ability to pay. The result is debt deflation for the economy at large and rising unemployment – but enrichment of the wealthiest 1% of the population as economies have become even more financialized.

This smooth continuum from the Bush to the Obama Administration masks the fact that there was a choice, and even a clear disagreement at the time within Congress, if not between the two presidential candidates, who seemed to speak as Siamese Twins as far as their policies to save Wall Street (from losses, not from actually dying) were concerned. Wall Street saw an opportunity to be grabbed, and its spokesmen panicked policy-makers into imagining that there was no alternative. And as President Obama’s chief of staff Emanuel Rahm noted, this crisis is too important an opportunity to let it go to waste. For Washington’s Wall Street constituency, the bold aim was to get the government to save them from having to take a loss on loans gone bad – loans that had made them rich already by collecting fees and interest, and by placing bets as to which way real estate prices, interest rates and exchange rates would move.

After September 2008 they were to get rich on a bailout – euphemized as “saving the economy,” if one believes that Wall Street is the economy’s core, not its wrapping or supposed facilitator, not to say a vampire squid. The largest and most urgent problem was not the inability of poor homebuyers to cope with the interest-rate jumps called for in the small print of their adjustable rate mortgages. The immediate defaulters were at the top of the economic pyramid. Citibank, AIG and other “too big to fail” institutions were unable to pay the winners on the speculative gambles and guarantees they had been writing – as if the economy had become risk-free, not overburdened with debt beyond its ability to pay.

Making the government to absorb their losses – instead of recovering the enormous salaries and bonuses their managers had paid themselves for selling these bad bets – required a cover story to make it appear that the economy could not be saved without the Treasury and Federal Reserve underwriting these losing gambles. Like the sheriff in the movie Blazing Saddles threatening to shoot himself if he weren’t freed, the financial sector warned that its losses would destroy the retail banking and insurance systems, not just the upper reaches of computerized derivatives gambling.

How America’s Bailouts Endowed a Financial Elite to rule the 21st Century

The bailout of casino capitalists vested a new ruling class with $13 trillion of public IOUs (including the $5.3 trillion rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) added to the national debt. The recipients have paid out much of this gift in salaries and bonuses, and to “make themselves whole” on their bad risks in default to pay off. An alternative would have been to prosecute them and recover what they had paid themselves as commissions for loading the economy with debt.

Although there were two sides within Congress in September 2008, there was no disagreement between the two presidential candidates. John McCain ran back to Washington on the fateful Friday of their September 26debate to insist that he was suspending his campaign in order to devote all his efforts to persuading Congress to approve the $700 billion bank bailout – and would not debate Mr. Obama until that was settled. But he capitulated and went to the debate. On September 29 the House of Representatives rejected the giveaway, headed by Republicans in opposition.

So Mr. McCain did not even get brownie points for being able to sway politicians on the side of his Wall Street campaign contributors. Until this time he had campaigned as a “maverick.” But his capitulation to high finance reminded voters of his notorious role in the Keating Five, standing up for bank crooks. His standing in the polls plummeted, and the Senate capitulated to a redrafted TARP bill on October 1. President Bush signed it into law two days later, on October 3, euphemized as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act.

Fast-forward to today. What does it signify when a right-wing cracker makes a more realistic diagnosis of bad bank lending better than Treasury Secretary Geithner, Fed Chairman Bernanke or other Bush-era financial experts retained by the Obama team? Without the bailout the gambling arm of Wall Street would have collapsed, but the “real” economy’s everyday banking and insurance operations could have continued. The bottom 99 percent of the U.S. economy would have recovered with only a speed bump to clean out the congestion at the top, and the government would have ended up in control of the biggest and most reckless banks and AIG – as it did in any case.

The government could have used its equity ownership and control of the banks to write down mortgages to reflect market conditions. It could have left families owning their homes at the same cost they would have had to pay in rent – the economic definition of equilibrium in property prices. The government-owned “too big to fail” banks could have told to refrain from gambling on derivatives, from lending for currency and commodity speculation, and from making takeover loans and other predatory financial practices. Public ownership would have run the banks like savings banks or post office banks rather than gambling schemes fueling the international carry trade (computer-driven interest rate and currency arbitrage) that has no linkage to the production-and-consumption economy.

The government could have used its equity ownership and control of the banks to provide credit and credit card services as the “public option.” Credit is a form of infrastructure, and such public investment is what enabled the United States to undersell foreign economies in the 19th and 20th centuries despite its high wage levels and social spending programs. As Simon Patten, the first economics professor at the nation’s first business school (the Wharton School) explained, public infrastructure investment is a “fourth factor of production.” It takes its return not in the form of profits, but in the degree to which it lowers the economy’s cost of doing business and living. Public investment does not need to generate profits or pay high salaries, bonuses and stock options, or operate via offshore banking centers.

But this is not the agenda that the Bush-Obama administrations a chose. Only Wall Street had a plan in place to unwrap when the crisis opportunity erupted. The plan was predatory, not productive, not lowering the economy’s debt overhead or cost of living and doing business to make it more competitive. So the great opportunity to serve the public interest by taking over banks gone broke was missed. Stockholders were bailed out, counterparties were saved from loss, and managers today are paying themselves bonuses as usual. The “crisis” was turned into an opportunity to panic politicians into helping their Wall Street patrons.

One can only wonder what it means when the only common sense being heard about the separation of bank functions should come from a far-out extremist in the current debate. The social democratic tradition had been erased from the curriculum as it had in political memory.

Tom Fahey: Would you say the bailout program was a success? …

Bachmann: John, I was in the middle of this debate. I was behind closed doors with Secretary Paulson when he came and made the extraordinary, never-before-made request to Congress: Give us a $700 billion blank check with no strings attached.

And I fought behind closed doors against my own party on TARP. It was a wrong vote then. It’s continued to be a wrong vote since then. Sometimes that’s what you have to do. You have to take principle over your party. [2]

Proclaiming herself a libertarian, Ms. Bachmann opposes raising the federal debt ceiling, Pres. Obama’s Medicare reform and other federal initiatives. So her opposition to the Wall Street bailout turns out to lack an understanding of how governments and their central banks can create money with a stroke of the computer pen, so to speak. But at least she was clear that wiping out bank counterparty gambles made by high rollers at the financial race track could have been wiped out (or left to settle among themselves in Wall Street’s version of mafia-style kneecapping) without destroying the banking system’s key economic functions.

The moral

Contrasting Ms. Bachmann’s remarks to the panicky claims by Mr. Geithner and Hank Paulson in September 2008 confirm a basic axiom of today’s junk economics: When an economic error becomes so widespread that it is adopted as official government policy, there is always a special interest at work to promote it.

In the case of bailing out Wall Street – and thereby the wealthiest 1% of Americans – while saying there is no money for Social Security, Medicare or long-term public social spending and infrastructure investment, the beneficiaries are obvious. So are the losers. High finance means low wages, low employment, low industry and a shrinking economy under conditions where policy planning is centralized in hands of Wall Street and its political nominees rather than in more objective administrators.

[1] Stephen Moore, “On the Beach, I Bring von Mises”: Interview with Michele Bachman, Wall Street Journal, June 11, 2011.

[2] CNN Republican Presidential Debate, Transcript, June 13, 2011, http://www.malagent.com/archives/1738