This week we began our investigation of effects of sovereign deficits on saving, reserves, and interest rates. As usual I will group responses by topic. I counted nine main topics. I’ll be very brief in presenting the questions (some of which were quite long!!) so please refer back to Blog 19 for the details.

Q1: Wray claims sovereign government can buy anything for sale in its own currency; but why can’t it just go to forex markets, get foreign currency, then buy everything for sale in ALL currencies?

A: Takes at least two to tango. Domestically, government ensures sellers by imposing a tax in its own currency. Hard to do that on foreigners in their own countries—impinges on sovereignty. So, for example, the US cannot force Italians to pay taxes in Italy in dollars. To buy stuff from Italians, our government MIGHT be forced to use euros. (Note, I did have a caveat—foreigners might take dollars, in which case there is no affordability problem.) So let us say Italians don’t want the cheap, risky dollars (Hah!). Yes the US can go to forex markets and trade dollars for euros. Here’s the problem: it is now subject to forex market demand for dollars. It can never run out of dollars, but the exchange rate can move against the US. At the extreme, it could find no takers even at an infinite exchange rate against the dollar. (Zimbabwe! Weimar!) I am not saying this is probable. I am just saying we need to be careful in our claims. Domestically, government can buy anything for sale if it is for sale in terms of its own currency. And it can create that demand by imposing taxes. Externally, all bets are off. If stuff is for sale only in foreign currency, the government of Rwanda might not be able to buy it.

Q2: Inflation. What causes it? Shortage of supply? External shocks? Excess demand? Unions? Can ELR deliver price stability?

A: Ahhhh, the question of the ages. Here is Keynes: “true inflation” only results once the economy exceeds the full employment level of demand. That is a useful definition, but not consistent with empirical measures—that usually rely on a consumer or producer basket, the index price of which can rise long before full employment. Bottlenecks (say, high tech goods and skilled labor) cause prices to rise. “Supply shocks” (a nice euphemism for OPEC conspiring to raise oil prices!) cause key commodities to rise in price—which causes prices to rise across the full range of output. And so on.

Note also that much, or even most, of inflation results from imputation of price increases to things that are not bought or sold at all (“shelter services”—the sheer joy of living in a house one owns). That gets into complicated discussions ( I wrote about it years ago at www.levy.org). So let us put it this way: beyond full employment, raising aggregate demand (or reducing supply) is almost certain to cause inflation. Before that, inflation is possible but not inevitable. Depends on a wide variety of factors—and is not necessarily a bad thing at all in any case. (Shifting the composition of the consumer basket due to changes of tastes can cause the Consumer Price Index to rise. Is that bad? Of course not—consumers changed their tastes.) The focus on inflation has become a phobia in the worst sense of the term. But in any case, yes, the employer of last resort program helps to stabilize prices—as we discuss in weeks to come.

Q3: The Fed sets the overnight rate but what about others? What if markets react against budget deficits, so the bond market vigilantes demand more blood in the form of higher rates?

A: As discussed, the Fed can set the overnight rate, plus the rate on any other financial assets it stands ready to buy and sell. It can peg the 10 year government bond rate, or the 30 year. It actually did that in WWII. But now it usually does not do that; and even under QE it used a backassward method to try to bring down long rates on Treasuries—trying to use quantities rather than prices to hit a price target! Dumb and Dumber. But whoever claimed Bernanke knows what he is doing? (Hint: he doesn’t. But I suspect you did not need the hint.)

Any rates the Fed does not target are set complexly—some more complexly than others. We used to set the saving and demand deposit rates (Remember Regulation Q? No? Ok you are younger than me. I used to get zero on my checking account and 5.25 max on my saving deposit, and I paid banks for the privilege of banking with them. Just you wait—it will be back to the future soon.) We set some loan rates. (Remember NDSL rates that benefitted students? No? Ok, ditto. Imagine 3% interest rates on student loans, with government forgiving half your debt if you became a teacher! Hey, today’s Real Housewives of Wall Street get similar deals! And they don’t even have to go to college. They just have to marry rich guys on Wall St.)

Leaving to the side government-managed interest rates, others are set by a complex of factors: markups and markdowns, credit and liquidity risks, expectations of Fed policy, expected exchange rate movements, and so on. Too complicated to discuss here. Let me just (cryptically) say that while the purchasing power parity theorem as well as the Fisher interest rate equations perform poorly, Keynes’s interest rate parity theorem holds up well. ‘Nuff said.

Bond vigilantes? Don’t sell them the bonds. Sovereign government NEVER needs to sell bonds. Just leave the reserves in the banks instead. Pay them zero or whatever the support rate is. Euthanize the rentier class, don’t bend over backward for the vigilantes. That was Keynes’s recommendation.

Q4: Can the CB manage the level of reserves by paying a support rate?

A: In the old days when the Fed paid zero on reserves, but had a target rate substantially above zero, the supply of reserves was completely nondiscretionary. The Fed accommodated. Now, it can “pump” trillions of reserves into banks and pay them 25 basis points—the support rate—and charge any bank that is short reserves 50bp. The fed funds rate will stay within that band. So, now, a QE-adopting Bernanke Fed can decide banks should hold $100 gazillion of reserves and buy every toxic waste trashy asset banks have—they are happy to give up the waste—and thereby increase reserves “exogenously”.

Why any Fed would want to do that is beyond me. But Bernanke’s Fed wants to do it. It will do QE3, just you wait.

Q5: Barbara argues that balance sheets are false for government.

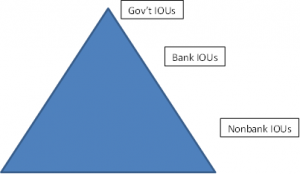

A: This sounds a lot like my buddies at the American Monetary Institute (AMI) who want to abolish accounting so that the government can create “debt-free” money. Look, accounting is certainly a human device. (Well, Apes have accounting records too—but they are somewhat more straight-forward. So far as we know they have not yet invented subprimes and credit default swaps.) But there is a logic behind it—to some extent you can say we “discovered” rather than “invented” double entry book-keeping. Frankly, I think anyone who thinks that we can change accounting so that we only look at the asset side and ignore the liability side has at least one screw loose. Government has a balance sheet; its IOUs are our assets. Its deficits are our savings. Changing the way we report the balance sheets will not change the reality. (Hey, banks have been cooking their accounting and they are still toast.) More below.

Q6: Deficits create excess reserves only if all else is equal.

A: Yes. But look at the scale. Budget deficits are in the tens and hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars. Required bank reserves are miniscule by comparison: a few months of budget deficits will completely satisfy all required reserve needs for the next decade. The flow of reserves that result from typical budget deficits will ALWAYS create excess reserves because required reserves grow much more slowly.

Q7: Isn’t the accounting of debits and credits reversed?

A: OK to simplify I use “T accounts” that are presented in every money and banking textbook. Bank loans are on the asset side of the bank’s balance sheet; demand deposits are on the liability side. Reverse that for the borrower. For the wonkier with a bit of business school education behind them, I strongly recommend this article: Ritter, “The flow-of-funds Accounts: A New Approach” (Jnl of Finance, May 1963) which goes through the balance sheet, the financial uses and sources approach, treatment of real and financial, and integration into flow of funds accounts. It sounds like a couple of commentators are confusing a balance sheet with sources and uses.

Q8: What if the budget deficit is too low to satisfy net financial saving desires by the private (and foreign) sectors? And the Fazzari paper is excellent!

A: Yes that happens. In that case, the private (and foreign) sector reduces spending, causing the budget deficit to widen. Now, to be clear, causation is complex. There can be many slips between lip and cup. As private sector spending falls, its income falls (sales fall, people get laid off) and that could either intensify the desire to save, or reduce it as people must dip into saving to avoid starvation.

And Steve Fazzari was my teacher, so how can I argue against his paper!

Q9: Provide more details on the process of setting interest rates in the current institutional environment.

A: Well, ignoring QE, we now have a Fed that sets the support rate (paid on reserves) and charges a higher rate to lend reserves; the market rate (fed funds rate) fluxes between the two. The best work on all this is by Scott Fullwiler. I’ll provide a bit more in later blogs—but it gets wonky.