Thank you for comments and questions. Let me divide the responses into several different issues.

1. “Sustainability Conditions” for Government Deficits

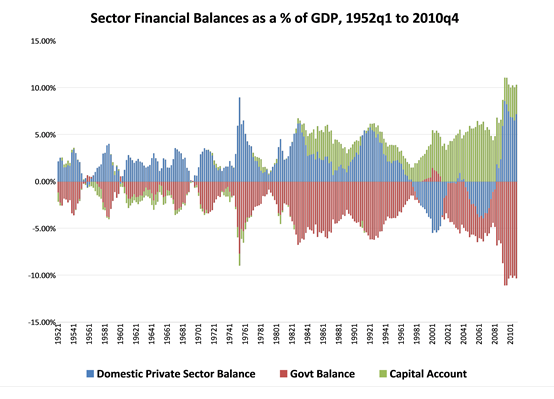

I said: “If you want to take a guess at what our “mirror image” in the graph above will look like after economic recovery, I would guess that we will return close to our long-run average: a private sector surplus of 2% of GDP, a current account deficit of 3% of GDP and a government deficit of 5% of GDP. In our simple equation it will look like this:

Private Balance (+2) + Government Balance (-5) + Foreign Balance (+3) = 0.

And so we are back to the concept of zero!”

Now I want to be clear, I said nothing to imply these particular sectoral balances would continue on through infinity to the sweet hereafter. What I gave was a contingent statement (what the balances would look like AFTER recovery and if we return to LONG-RUN AVERAGES—that is to say, average stances over the past 30 years or so, taking into account trends—essentially just eye-balling the 3 sectors graph provided in the blog). I have made no projection that we actually WILL recover, and it is certainly possible that even after recovery our private sector balance will remain in high surplus. Let us say it remains at 6% (which would be higher than average but consistent with an attempt to delever debt—that is, to keep consumption low in order to pay down debt). In that case, and again assuming the foreign balance remains a positive 3% (that is, our current account deficit is 3%) then the government will remain in deficit of 9% (more or less where it is now). I will not place probabilities on these two outcomes—I think the original statement is more likely—because my main point is simply that taking balances of each of the 3 sectors, the overall balance must be 0.

For those who would like to balance the government budget, the burden is on them to tell me what the implied outcome for the private and foreign sectors will be. If we are not going to return to the disastrous “Goldilocks” outcome with the private sector running deficits, then a huge adjustment will be necessary in the foreign balance in order to have a balanced government budget with a private sector surplus. Virtually none of the deficit hawks consider this. But, again, I would like to hear their explanation for how we will get the current account into surplus.

On to the sustainability conditions. It has become trendy among economist wonks to look at government budget stances to determine whether they could continue forever. Many objections could be raised to such purely mental exercises. An obvious one is that no government has ever lasted forever—and so any such exercise is a waste of time. Ok that one is not something we want to contemplate. Economist Herb Stein quipped that unsustainable processes will not be sustained. Something will change. That gets us somewhat closer to the problem with such approaches. And finally, if we are dealing with sovereign budget deficits we must first understand WHAT is not sustainable, and what is. That requires that we need to do sensible exercises. The one that the deficit hysterians propose is not sensible.

Let us first look at a somewhat simpler unsustainable process. Suppose that some guy—we’ll use the name Ramanan—decides to replicate the “Supersize me” experiment (based on the 2004 documentary by Morgan Spurlock). His caloric intake is 5000 calories a day, and he burns 2000 daily. The excess 3000 calories lets him gain one pound of body weight each day. If he weighed 200 pounds on January 1, by the end of the year he weighs 565 pounds. After 100 years he’s up to 36,700 pounds—a bit on the pudgy side. But we don’t stop there. After 100,000 years he weighs 36,700,000 pounds, and after a few million years, he’s heavy enough to affect the earth’s spin on its axis and its revolutions about the sun. But, according to our policy wonks, that still is not a long enough period—we’ve got to carry this out to infinity, at which point, Ramanan is infinite sized, like the universe, and if he is growing faster than the expansion of the universe, the entire rest of the universe will eventually be infinitesimally smaller than Ramanan. I guess he’s become the black hole of the universe (but I’m no physicist or biologist). So, yes this is unsustainable. Aren’t we all clever?

But would the process actually work that way? Of course not. First, Ramanan is not going to live an infinite number of years; second, he’s either going to blow up (literally) or go on a diet; and third, and most important, his body is going to adjust. As his body mass increases, he will burn more than 2000 calories a day—perhaps he’ll get up to a 5000 calorie a day burn-rate—and his body will use the food in a less efficient manner. So he will stop gaining weight long before he becomes the universe’s black hole. Herb Stein was right.

Our little mental exercise was fundamentally flawed. It assumed a fixed caloric input (flow) and a fixed caloric burn-rate (consumption flow) with the difference between the two accumulating as a stock (weight gain) at a fixed rate (essentially, “savings”). No adjustments to behavior or metabolism are allowed. And then the whole absurd set-up is carried to the ultimate absurdity by the use of infinite horizon projections. Anything carried to a logical absurdity is unsustainable. As you will see, this is the rigged game used by deficit warriors to “prove” the US Federal budget deficit is unsustainable.

The trick used by deficit warriors is similar but with the inputs and outputs reversed. Rather than caloric inputs, we have GDP growth as the input; rather than burning calories, we pay interest; and rather than weight gain as the output we have budget deficits accumulating to government debt outstanding. To rig the little model to ensure it is not sustainable, we have the interest rate higher than the growth rate—just as we had Ramanan’s caloric input at 5000 calories and his burn rate at only 2000—and this will ensure that the debt ratio grows (just as we ensured that Ramanan’s waistline grew without limit). Let us see how this works.

We will start with a simple example similar to the one used in our blog and response last week. Let us have two sectors, government and private. Our government follows the Goldilocks model, spending less than its income (tax revenue); the private sector by identity runs a deficit (spends more than its income). We know this means the private sector is running up debt, held by the government as its asset (surpluses are realized in the form of private sector IOUs). The private sector must service the debt by paying interest; that of course adds to its deficit (interest is additional spending it must make out of its income). In comparison to our Supersizing Ramanan, the sustainability conditions will be determined by the interest rate paid, the growth rate of income (or GDP), and the deficit of the private sector.

Jamie Galbraith laid out the typical model used to evaluate sustainability of deficit spending as follows:

The key formula is:

Δd = –s + d * [(r – g)/(1 + g)]

Here, d is the starting ratio of debt to GDP, s is the “primary surplus” or budget surplus after deducting net interest payments (as shares of GDP), r is the real interest rate, and g is the real rate of GDP growth. (http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/?docid=1379)

Now, this is wonky but the key idea is that (given a relation between the primary surplus and starting debt–both as ratios to GDP) so long as the interest rate (r) is above the growth rate (g) the debt ratio is going to grow. (Jamie has put these key terms in “real”—that is inflation adjusted—terms but that really does not matter; we can keep it all in nominal terms since “deflation” by the inflation rate merely reduces all terms by the inflation rate). Note that the starting debt ratio (d) as well as the primary surplus (what the private sector’s budget would be if it did not have to pay interest) also play a role. (Galbraith proves that the starting debt ratio does not matter much—just as Ramanan’s initial weight will not matter since in any case he will grow to an infinite size.) But we do not need to get too hung up in math to see that all things equal if the interest rate is above the growth rate, we get a rising debt ratio. If we carry this through eternity, that ratio gets big. Really big. Ok that sounds bad. And it is. Remember, that is a big part of the reason that the GFC hit—overindebted private sector. The GFC is the equivalent to an explosion of Ramanan that would prevent him from growing to an infinite size. (A debt diet would have been far preferable, but Greenspan and Bernanke opposed “interfering” with Wall Street lender fraud.)

Now let us change all this around. Let us say that the government runs a continuous budget deficit while the private sector runs a surplus. We can obtain the same equation. It appears that a continuous government budget deficit implies a continuously rising debt to GDP ratio and surely that is unsustainable. (See the appendix below for more complex math.)

But wait a minute. Is such a mental exercise sensible? We already saw that our supersizing Ramanan is going to adjust: he will diet, explode, increase his metabolism, and reduce the efficiency of his absorption of calories. If he does not explode, he will reach some “equilibrium” in which his intake of calories will equal his burn-rate so that his waistline will stop growing. What about our supersizing government? Here are the possible consequences of a persistent deficit that implies rising interest payments and debt ratios:

- Inflation: this tends to increase tax revenues so that they grow faster than government spending, thus lowering deficits. (Many, including Galbraith, would point to the tendency to generate “negative” interest rates.) In other words the growth rate will rise above the interest rate, and reverse the dynamics so that the debt ratio stops growing. (That is equivalent to an increase of Ramanan’s caloric burn rate—so he stops growing.)

- Austerity: government can try to adjust its fiscal stance (increasing taxes and reducing spending to lower its defict). Of course, it takes “two to tango”—raising tax rates might not change the government’s balance. It could lower growth rates, and thereby actually increase the rate of growth of the debt ratio.

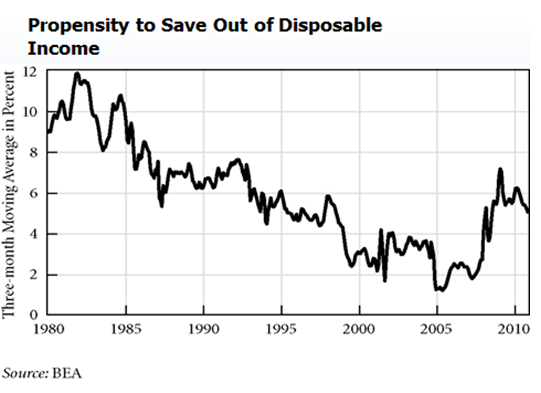

- The private sector will adjust its flows (spending and saving) in response to the government’s stance. If government continually spends more than its income, it will be adding net wealth to the private sector; and its interest payments will add to private sector income. It is not plausible to believe that as the government’s debt ratio goes toward infinity (which means that the private sector’s net wealth ratio goes to infinity) there is no induced spending in the private sector. That is usually called the “wealth effect”. In other words, government debt is private wealth and as private wealth grows without limit this will eventually cause spending to rise relative to private sector income—reducing government deficits. In addition, private sector income includes government interest payments, so rising government interest payments on its debt could induce consumption. When all is said and done, the private sector will not be happy consuming less than its income flow—given its rising wealth—and will adjust its saving behavior. If the private sector tries to reduce its surpluses, this can be done only by reducing the government sector’s deficits. It takes two to tango and the likely result is that tax revenues and consumption will rise, the government’s deficit will fall, and the private sector’s surplus will fall.

- Government deficit spending and interest payments could increase the growth rate; it can be pushed above the interest rate. This changes the dynamics and can stop the growth of the debt ratio.

- The interest rate is a policy variable (as will be discussed in subsequent weeks). Ignoring all the dynamics discussed in the previous points, to avoid an exploding debt ratio, all the government needs to do is to lower the interest rate below the economic growth rate. End of story, sustainability achieved.

Finally, and this is the most contentious point. Suppose none of the dynamics just discussed come into play, so the government’s debt ratio rises on trend. Will a sovereign government be forced to miss an interest payment—no matter how big that becomes? The answer is a simple “no”. It will take weeks of explication of MMT to explain why. But let us put this in the simple terms that Chairman Bernanke used to explain all the Fed spending to bail-out Wall Street: government spends using keystrokes, or, electronic entries on balance sheets. There is no technical or operational limit to its ability to do that. So long as there are keyboard keys to stroke, government can stroke them to produce interest payments credited to balance sheets.

And that finally gets us to the difference between perpetual private sector deficit spending versus perpetual government sector deficits: the first really is unsustainable while the second is not. Now, I want to be clear. We have argued that persistent government budget deficits that increase government debt ratios and thus private wealth ratios will lead to behavioral changes. They could lead to inflation. They could lead to policy changes. Hence, they are not likely to last “forever”. So when I say they are “sustainable” I merely mean in the sense that sovereign government can continue to make all payments as they come due—including interest payments—no matter how big those payments become. It might choose not to make those payments. And the mere act of making those payments will likely cause changes in growth rates and budget deficits and growth of debt rations.

2. “Sustainability” of Current Account ratios:

In the quote at the top of this response there was also a contingent statement about US current account deficits. To be more clear (and thus to respond to comments), the current account includes the balance of trade (and, more broadly, the balance between exports and imports) plus some other items including “factor payments” (interest and profits paid and received). For the US, we obviously run a trade deficit (and exports are less than imports), but the factor payments are in our favor (we receive more in profits and interest from abroad than we pay to foreign creditors and owners). In any event, our negative current account balance is offset by a positive capital account balance. To put it simply—there is a “flow” of dollars abroad due to the current account deficit that is matched by the “flow” of dollars back to the US due to our capital account surplus. This is often (misleadingly) presented as US “borrowing” of dollars to “pay for” our trade deficit. We could just as well put it this way: the US imports more than it exports because the rest of the world wants to accumulate savings in dollar-denominated assets. I do not want to go into that in detail since it is the subject of later blogs.

But here’s the question. Is a continuous current account deficit possible? A simple answer is yes, so long as “two want to tango”: if the rest of the world wants dollar assets and Americans want rest of world exports (imported to the US), this will continue. But, hold it, say the worriers. As the rest of the world accumulates dollar claims on the US, they also receive interest payments. That is a factor payment that increases our current account deficit. You can see the relation to the point above about government deficits and interest payments. The world will be flooded with dollars twice over: once from our excessive propensity to import and once from our interest payments on debt.

But here is the interesting point: even though the US is the “biggest debtor on earth”, those factor payments flow in our favor. We pay extremely low interest rates and profit rates to foreigners, and earn much higher interest rates and profits on our holdings of foreign investments and debt. Why is that? Because the US is the safest investment on earth. Anytime there is a financial crisis anywhere in the world, where do international investors run? To the US dollar. Ironically, that happens even when the crisis begins in the US! Why? The US has a sovereign government with a sovereign currency. Its interest rate is set by the Fed, which can always set the rate below the US growth rate (and, indeed, as Galbraith points out, the inflation-adjusted interest rate is often below the “real” growth rate). In spite of the deficit hysteria whipped up by hedge fund billionaire Pete Peterson, no investor in her right mind believes there is any default risk on US Treasury debt. So when global fears rise, investors run to the dollar. This could change, but not in your lifetime.

In short, I make no projection about continued US current account deficits but I believe they will continue far longer than anyone imagines. They are sustainable. They will be sustained until the rest of the world decides not to accumulate more dollars and Americans decide they really do not want the cheap junk and environment-destroying oil produced by the rest of the world. When that will happen, I do not know. It is nothing to lose sleep over. Yes we can calculate “sustainability conditions” but it would just be an exercise in mental masturbation. We’ve already done enough of that. I suppose it is titillating but ultimately unsatisfying.

3. Briefly there were several other points raised.

There were some about maldistribution of income as a contributing cause of the private sector deficit. Agreed. There were some questions about stocks and relations to flows. Some of that is treated above but much more will come in the next series of blogs. There were points made about need to regulate Wall Street. Yes! There were questions about QE and the difference between helicopter drops and fiscal policy. Put it this way: Treasury SPENDS money things into existence, the Fed LENDS money things into existence. The first adds income and net wealth, the second only transforms balance sheets. This will be explained in more detail later.

Appendix:

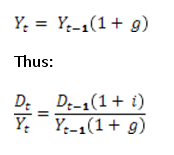

Government debt outstanding (D) follows the following law of motion:

That is, every year, assuming the debt never matures, the outstanding debt increases by the size of the deficit. The deficit is the difference between government spending (G), taxes (T) plus interest payments on outstanding debt (iD)

Let us assume to simplify that G = T so: therefore

The gross domestic product (Y) grows at a rate g and so follows the following law of motion:

Let us find the limit of this ratio:

Following the same logic for Y we get (noting d the debt to gdp ratio)

It is pretty clear that if i > g then the ratio tends toward infinity when n tends toward infinity; and toward zero otherwise. If g = i then dt = d0 for all t.

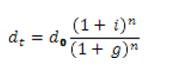

The complication of the deficit to GDP ratio at 5% would mean:

Without going too far into the implications we have:

Therefore by doing a recursive calculation we get:

As n tends toward infinity dt also does. Note that a given deficit to gdp ratio means that deficit has to explode as gdp increases.

Thanks: to James Galbraith and Eric Tymoigne.