By William K. Black

Mitt Romney chose to unveil the economic plank of his campaign for the Republican nomination with a speech in Aurora, Colorado decrying banking regulation. He could not have picked a more symbolic location to make this argument, for Aurora is the home and name of one of the massive financial frauds that caused the Great Recession. Lehman Brothers’ collapse made the crisis acute and Lehman’s subsidiary, Aurora, doomed Lehman Brothers. Lehman acquired Aurora to be its liar’s loan specialist. The senior officers that Lehman put in charge of Aurora, which was inherently in the business of buying and selling fraudulent loans, set its ethical plane at subterranean levels.

Aurora sealed Lehman’s fate by serving as a “vector” that spread an epidemic of mortgage fraud throughout the financial system and caused catastrophic losses far greater than Lehman’s entire purported capital. Aurora epitomizes what happens when we demonize the regulators and create regulatory “black holes.”

Romney literally demonized banking regulators as “gargoyles” and claimed that banking regulations and regulators were the cause of the economy’s weak recovery.

On April 20, 2010, I testified before the Committee on Financial Services of the United States House of Representatives regarding Lehman’s failure. I was the witness chosen by the (then) Republican minority because they wished to have testimony from an experienced and successful financial regulator who would pull no punches in critiquing the failures of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve (the Fed), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with regard to Lehman. The Republicans’ target was the former President of the FRBNY, Timothy Geithner.

My House testimony explained why Aurora was the key to understanding Lehman’s failure and the causes of the financial crisis.

Lehman was a “control fraud.” That is a criminology term that refers to situation in which the persons controlling a seemingly legitimate entity use it as a “weapon” (Wheeler & Rothman 1982) of fraud (Black 2005). Financial control frauds’ “weapon of choice” for looting is accounting.

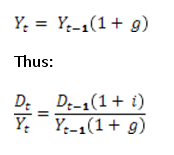

Lehman’s nominal corporate governance structure was a sham. Lehman was deliberately out of control with regard to “risk” in its dominant operation – making “liar’s loans.” Lehman did not “manage” the risk of making liar’s loans. It engaged in massive, fraudulent transactions that were “sure things” (Akerlof & Romer 1993). The Valukas Report … provides further evidence of the accuracy of George Akerlof and Paul Romer’s famous article – “Looting: Bankruptcy for Profit.” The “looting” that Akerlof & Romer identified is a “sure thing” in both directions – firms that loot through accounting scams will report superb (fictional) income in the short-term and catastrophic losses in the long-term.

The value of Lehman’s Alt-A mortgage holdings fell 60 percent during the past six months to $5.9 billion, the firm reported last week.

This roughly $9 billion loss, in 2008, was an important factor in destroying Lehman, but it represents only losses on liar’s loans still held in portfolio. Aurora specialized in making liar’s loans and Aurora’s loans caused massive losses because they were pervasively fraudulent. Lehman sold tens of billions of dollars of liar’s loans through Aurora and a subsidiary (BNC Mortgage) that specialized in making subprime loans – roughly half of which were liar’s loans by 2006. The purchasers of these fraudulent loans had the legal right and economic incentive to require Lehman to repurchase the loans, which would have far exceeded Lehman’s reported capital. Making and selling fraudulent liar’s loans doomed Lehman. Lehman was one of the largest vectors that spread fraudulent mortgage paper throughout much of Europe and the United States.

Lehman had become the only vertically integrated player in the industry, doing everything from making loans to securitizing them for sale to investors.

***

Lehman was a dominant player on all sides of the business. Through its subsidiaries – Aurora, BNC Mortgage LLC and Finance America – it was one of the 10 largest mortgage lenders in the U.S. The subsidiaries fed nearly all their loans to Lehman, making it one of the largest issuers of mortgage-backed securities. In 2007, Lehman securitized more than $100-billion worth of residential mortgages.

These demands posed a much larger problem: contagion. Because these CDOs were thinly traded, many of them did not yet reflect the loss in value implied by their crumbling mortgage holdings. If Bear Stearns or its lenders began auctioning these CDOs off, and nobody wanted to buy them, prices would plummet, requiring all banks with mortgage exposure to begin adjusting their books with massive writedowns.

Lehman, despite its huge mortgage exposure, appeared less scathed than some. Mr. Fuld was awarded $35-million in total compensation at the end of the year.

The volume of liar’s loans and subprime loans was everything – as long as Lehman could sell the liar’s loans to other parties. Volume created immense real losses, but it also maximized Dick Fuld’s compensation. Nonprime loans drove Lehman’s (fictional) gains in income and capital under Fuld.

Lehman’s real estate businesses helped sales in the capital markets unit jump 56 percent from 2004 to 2006, faster than from investment banking or asset management, the company said in a filing. Lehman reported record earnings in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

As MARI, the mortgage lending industry’s own anti-fraud experts, warned the industry in 2006, making liar’s loans is an “open invitation to fraudsters.” Even Lehman’s internal studies found, by reviewing only the loan files, exceptional levels of fraud.

Mark Golan was getting frustrated as he met with a group of auditors from Lehman Brothers.

It was spring, 2006, and Mr. Golan was a manager at Colorado-based Aurora Loan Service LLC, which specialized in “Alt A” loans, considered a step above subprime lending. Aurora had become one of the largest players in that market, originating $25-billion worth of loans in 2006. It was also the biggest supplier of loans to Lehman for securitization.

Lehman had acquired a stake in Aurora in 1998 and had taken control in 2003. By May, 2006, some people inside Lehman were becoming worried about Aurora’s lending practices. The mortgage industry was facing scrutiny about billions of dollars worth of Alt-A mortgages, also known as “liar loans”– because they were given to people with little or no documentation. In some cases, borrowers demonstrated nothing more than “pride of ownership” to get a mortgage.

That spring, according to court filings, a group of internal Lehman auditors analyzed some Aurora loans and discovered that up to half contained material misrepresentations. But the mortgage market was growing too fast and Lehman’s appetite for loans was insatiable. Mr. Golan stormed out of the meeting, allegedly yelling at the lead auditor: “Your people find too much fraud.”

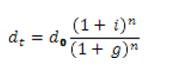

After the FBI warned in September 2004, that there was an “epidemic” of mortgage fraud, after Lehman’s internal auditors found endemic fraud in their liar’s loans, after MARI warned the industry in 2006 that studies of liar’s loans found a fraud incidence of 90%, after the bubble had stalled in 2006, and after scores of mortgage banks that specialized in making nonprime loans failed – Lehman significantly increased the rate at which Aurora made liar’s loans. In 2006, Aurora originated roughly $2 billion a month.

BNC was Lehman’s subsidiary that specialized in subprime loans. By 2006, roughly half of its loans were liar’s loans to borrowers with poor credit records.

Lehman’s pattern of conduct seems bizarre because no honest firm would make liar’s loans. The pattern, however, is optimal for an accounting control fraud. The people who control fraudulent lenders optimize their compensation by maximizing the bank’s short-term reported income. The “recipe” for maximizing fictional income (and real losses) has four ingredients:

- Extremely rapid growth by

- Making poor quality loans at a premium yield while employing

- High leverage and

- Providing only grossly inadequate allowances for loan and lease losses (ALLL)

The officers controlling a fraudulent lender find it necessary to eviscerate the bank’s underwriting in order to be able to make large amounts of bad loans. The managers deliberately create a fraud-friendly culture, and Aurora demonstrated how extreme the embrace of fraud could become.

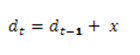

The HR lady pulled Michael Walker into a room and told him he was fired.

The reason: Talking to the FBI. It was a violation of the company’s privacy policy.

“I was stunned,” Walker told me. “I couldn’t believe it. But that’s what she said.”

Walker, a “high-risk specialist,” was then walked out of the building as if he were the risk. His job at Aurora Loan Services LLC, Littleton, Colo., ended on Sept. 4, 2008.

His job was to uncover mortgage fraud. But he claims he was fired for doing it. In a lawsuit recently filed in Denver District Court, he claims Lehman’s mortgage subsidiary wanted to remain profitably unaware of fraud.

Aurora [personnel] got paid by loan volume, not by loan quality.

Consequently, Walker and his fraud-seeking colleagues were always busy.

“They just absolutely flooded us with work,” he said. “There was no way we could possibly keep up with it. And that’s what they wanted.

“They were putting the loans into an investment trust,” he explained. “When they became aware of fraud, they had to buy those loans back out of the trust. So it ended up costing them money.”

But Walker couldn’t play this game. A “Suspicious Activity Report” that he filed in 2006 led to interviews with the FBI and the IRS in 2008, and then ultimately to his bizarre dismissal.

Lehman’s senior managers consciously chose to take the unethical path because they knew it generate extraordinary reported income in the short-term, which would maximize their compensation. Prior to becoming one of the world’s largest purchasers and sellers of nonprime loans through Aurora and BNC, Lehman had eagerly embraced fraudulent and predatory lending. The officers who controlled Lehman also showed in this earlier episode that they would choose that short-term reported income that maximized their compensation even when they were warned that it was produced by fraud and abuse of the customers and knew that the loans would produce large losses,

Mr. Hibbert was a vice-president at Lehman Brothers and he’d been sent to meet First Alliance founder Brian Chisick to see if Lehman could form some kind of relationship with the mortgage lender.

[Hibbert] pointed out that “there is something really unethical about the type of business in which [First Alliance] is engaged.”

Mr. Chisick had become one of the biggest players in subprime loans. First Alliance’s annual revenue had doubled in four years to nearly $60-million (U.S.) and its profit had increased threefold to $30-million.

“It is a sweat shop,” [Hibbert] wrote. “High pressure sales for people who are in a weak state.” First Alliance is “the used car salesperson of [subprime] lending. It is a requirement to leave your ethics at the door. … So far there has been little official intervention into this market sector, but if one firm was to be singled out for governmental action, this may be it.”

Despite the warning, Lehman officials recommended a $100-million loan facility for First Alliance. Mr. Chisick turned it down, but he agreed to take a $25-million line of credit and hire Lehman to work with Prudential on several securitizations.

At this juncture, Hibbert’s warnings of a governmental response proved accurate. Various state Attorneys General began to sue First Alliance for consumer fraud. Prudential terminated its ties with the lender.

But Lehman jumped at the opportunity to move in. Senior vice-president Frank Gihool asked Mr. Hibbert to pull together a review of First Alliance for Lehman’s credit risk management team. Mr. Hibbert once again marvelled at the company’s operations and financial outlook. But he also said the lawsuits posed a serious problem. The allegation about deceptive practices “is now more than a legal one, it has become political, with public relations headaches to come,” he wrote.

Nonetheless, on Feb. 11, 1999, Lehman approved a $150-million line of credit, and became the company’s sole manager of asset-backed securities offerings. The bottom line for Lehman was made clear in another internal report: The firm expected to earn at least $4.5-million in fees.

But within a year, the weight of the lawsuits crippled First Alliance. On March 23, 2000, the company filed for bankruptcy protection. Mr. Chisick managed to walk away with more than $100-million in total compensation and stock sales over four years. Lehman, owed $77-million, collected the full amount, plus interest.

First Alliance eventually settled the lawsuits filed by the state attorneys, agreeing to pay $60-million. In the California class-action case, a jury found Lehman partially responsible for First Alliance’s conduct and ordered the firm to pay roughly $5-million.

Romney is Echoing the Anti-regulatory Dogma that Caused the Crisis

Aurora and BNC Mortgage were regulatory “black holes.” The Fed had unique authority under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA) to regulate all mortgage lenders and had unprecedented practical leverage during the crisis because of its ability to lend to investment banks and convert them to commercial bank holding companies. Fed Chairmen Greenspan and Bernanke, despite pleas from Dr. Gramlich, refused to use this authority to close the regulatory black hole. Bernanke finally, under repeated pressure from Congressional Democrats, used the Fed’s HOEPA authority in August 2008 – over a year too late to even minimize losses. Greenspan and Bernanke were chosen to lead the Fed because of their intense, anti-regulatory dogma. Greenspan was notorious for his assertion that fraud provided no basis for regulation. He believed that financial markets automatically excluded fraud.

The SEC was equally notorious for its anti-regulatory policies. It created the disgraceful non-regulation regulation of Lehman and its four sister investment banks. The Consolidated Supervised Entities (CSE) program never made the SEC a real “primary regulator.” The SEC is incapable, as constituted, staffed, and led to be a primary regulator of anything – and that includes the rating agencies. “Safety and soundness” regulation is a completely different concept than a “disclosure” regime. The SEC’s expertise, which it has allowed to rust away for a decade, is in enforcing disclosure requirements. The SEC did not have the mindset, rules, or appropriate personnel to make the CSE program a success even if the agency had been a “junk yard dog.” Given the fact that the SEC was self-neutered by its leadership during the period Lehman was in crisis in 2001-2008, there was no chance that it would succeed even if the CSE been a real program.

The reality is that the CSE was a sham. The EU announced that it would begin regulating foreign investment banks doing business in the EU unless they were subject to consolidated supervision by their domestic regulator. The U.S., however, had no consolidated supervision of investment banks. The five largest U.S. investment banks were scared of the prospect of EU regulation. Their solution was for the SEC to create a faux regulatory system. The SEC assigned three staffers to be primarily responsible for each of the five, massive investment banks. In order to examine and supervise an entity of their size and complexity, a realistic staff level would begin at 150 regulators per investment bank.

The SEC’s only hope with respect to Lehman was to form an effective partnership with the Fed. An SEC/Fed partnership would at least have some chance. The Valukas report reveals that the FRBNY staff at Lehman recognized that the SEC’s staff at Lehman’s offices was not capable of understanding its financial condition.

Why we suffered the Great Recession and such a slow recovery

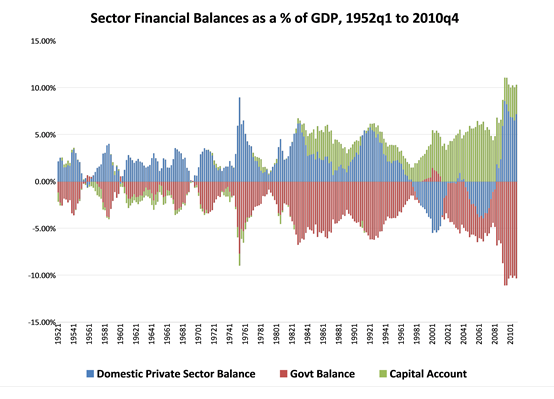

The primary cause of severe bank failures has long been senior insider fraud (James Pierce, The Future of Banking (2001). We know the characteristics that cause the criminogenic environments that produce the epidemics of accounting control fraud that cause our recurrent, intensifying crises. Two of the most important factors are the “three de’s” – deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization – and perverse executive, professional, and employee compensation. These two factors were principally responsible for creating the epidemic of mortgage fraud that drove our crisis. Financial regulation was effectively destroyed in the U.S.

The primary function of financial regulators is to serve as the “regulatory cops on the beat.” “Private market discipline” was an oxymoron – financial firms are supposed to provide the discipline by denying credit to poorly managed and overly risky firms. They are supposed to be impervious to fraud. The reality is that they fund the frauds’ rapid growth. Fraud begets fraud. George Akerlof warned of this perverse “Gresham’s” dynamic in his famous 1970 article about “lemon’s” markets. When fraud provides a competitive advantage market forces become perverse and drive ethical firms from the marketplace. Effective, vigorous financial regulation is essential to break this Gresham’s dynamic. The regulatory cops on the beat must take the profit out of fraud.

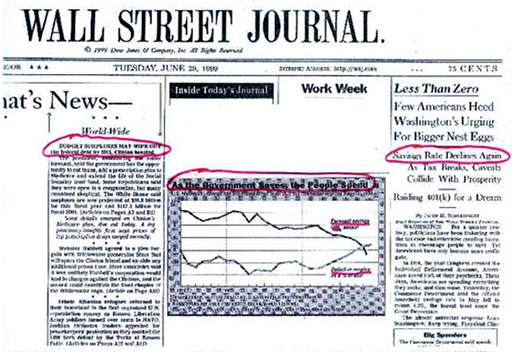

There are several reasons why the economic recovery is weak and there is a great danger of recurrent recessions. My colleagues on this blog have explained the macroeconomic reasons so I will concentrate on the regulatory barriers to recovery. Suffice it to say that my colleagues have shown that the recovery is not weak primarily due to credit restraints by banks on lending to corporations. The regulatory barriers to recovery are the opposite of what Romney asserts. Financial regulation in the U.S. remains extraordinarily weak. President Obama has largely kept in power and even promoted Bush’s financial wrecking crew. Larry Summers and Timothy Geithner are fierce anti-regulators. The Republicans have blocked vital appointments to the Fed – under the claim that a Nobel Prize winner in economics lacks sufficient expertise to serve on the Fed. The Republicans, while claiming that Fannie and Freddie pose a critical risk to the nation; have blocked the appointment of a superbly qualified head of the agency that is supposed to regulate Fannie and Freddie. The Republicans have blocked the appointment of Elizabeth Warren to head the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. Warren (a) warned of the coming nonprime disaster, (b) is superbly qualified to lead the bureau, and (c) is a remarkably pleasant and unassuming Midwesterner. The head of the SEC was named based on her experience as a failed leader of self-regulation. Bernanke named as the Fed’s top supervisor an anti-regulatory economist with no experience in examination or supervision. Bernanke then, absurdly, claimed that his appointment made the agency more inter-disciplinary. The reality is that it simply made theoclassical economists dominant in the one senior professional post that previously provided the Fed with an alternative policy perspective and real expertise. Attorney General Holder has largely continued the Bush administration’s policy of allowing the elite bank frauds to proceed with impunity.

The Republicans are trying to force severe cuts in the already inadequate budgets of the financial regulatory agencies. The flash clash revealed that the SEC does not have the internal capacity to monitor or even study retrospectively hyper-trading, which has become increasingly dominate. The SEC will not be provided with sufficient budget to even develop a system to monitor and study hyper-trading. The commodity markets are being subjected to exceptional manipulation. The Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has announced that it cannot afford to develop the systems essential to detect and track commodity speculation. Instead of demanding that the CFTC develop such an essential system the Republicans are seeking to slash the CFTC’s already grossly inadequate budget.

Romney’s claim that this group of understaffed and funded regulators led by senior anti-regulators constitutes “gargoyles” that have terrified the systemically dangerous institutions (SDIs) that dominate our finance system is ludicrous. There isn’t an SDI in the U.S. that fears its regulators. The regulators are like gargoyles – they may scare children but one soon learns that they are immobile stones that do not see, bite, or even growl. They are perches and canvasses for pigeons and their droppings.

Epidemics of accounting control fraud cause severe economic crises and harm recoveries in myriad ways. First, fraud causes far more severe losses. Second, fraud erodes trust because the essence of fraud is the creation and betrayal of trust. Trust can take many years to recover. The number of middle class Americans willing to invest in the stock market has still not recovered from the Enron era frauds. Third, as Akerlof & Romer (1993) warned, accounting control fraud epidemics can cause bubbles to hyper-inflate. Severe bubbles make markets grossly inefficient. Japan demonstrates that it can take over a decade for the prices to fall to levels where the markets will “clear.” The catastrophic nature of the losses and their concentration in financial institutions leads to the temptation to change the accounting rules to cover up the banks’ losses. We refused to do so during the S&L debacle and the result was a prompt recovery. We, like Japan, gave in to the banks’ demands during this crisis and the result is an impaired recovery. Fourth, the endemic mortgage fraud by lenders led to endemic foreclosure fraud because fraudulent lenders (a) keep extremely poor records and (b) a number of the largest servicers are staffed with personnel from the firms that made the fraudulent loans. The foreclosure fraud is harmful both because it defrauds the innocent and because it shields the most abusive borrowers from prompt foreclosures. Fifth, the fraud and the hyper-inflated bubble lead to a severe drop in private wealth and demand and household pessimism. The household sector has not been able to provide the demand to produce a strong recovery. Sixth, because we pretend that insolvent banks are healthy and keep them under the leadership of the inept and even fraudulent managers who caused them to become insolvent we end up with Japanese-style crippled banks that prefer to clip coupons rather than make commercial loans.

Romney is replaying the absurd and harmful propaganda of 1986-1987. S&L regulation was critically weak, which is what made the S&L industry so criminogenic. The industry trade association, however, claimed that regulation was oppressive. We, the S&L Federal Home Loan Bank Board Chairman Edwin Gray with any funds and any additional regulatory powers to counter the accounting control frauds that were running wild. Instead, in the Competitive Equality in Banking Act of 1987 (CEBA), Congress mandated “forbearance” designed to gut our power to close the frauds. This was not Congress’ intent – they did not consciously seek to aid the frauds. The worst S&L frauds, however, formed what a prominent CEO called a “Faustian bargain” with the S&L trade association to counter our proposed legislation. The result of that Faustian bargain was that language was inserted in our proposed bill that was framed by the frauds’ lobbyists for the express purpose of making it far more difficult for us to close the frauds. Until we took on their political patrons and spent months explaining to members of Congress, their staffs, and the media how the proposed amendments would damage our ability to act effectively against the frauds these claims that the regulators were ogres were taken as true by most politicians. All their political contributors said it was true. The reality was, of course, the opposite as virtually everyone now agrees. S&L regulation had been nearly non-existent. With the aid of Representatives Gonzalez, Leach, Carper, and Roemer and Senator Gramm (yes, that Senator Gramm!) we were able to make subtle changes in the CEBA bill that undid the worst of the frauds’ amendments.

Will the Obama administration be willing to fight like we did to save the effort to put the fraudulent S&Ls in receivership, remove the scam accounting rules, toughen regulation, and prosecute the fraudulent senior officers? Or will it give in to Romney’s propaganda and its desire to raise vast sums in political contributions from finance executives by weakening the already criminally weak Dodd-Frank Act? The administration’s most recent action has been to delay adoption of the rules implementing the Act. It wants banks to be able to continue the disastrous practices that made the crisis worse and that the Dodd-Frank Act sought to prohibit.

Here are the key passage and question arising from Romney’s speech:

“Almost everything the president did had the opposite effect of what was intended,” Romney said. “He said, okay, we’re not going to re-regulate the banking sector. Well, what he caused was the banking sector to pull back, and that’s the very sector that’s got to step forward to help get the economy on its feet again.”

The question to President Obama is: “Was Mr. Romney correct when he said that you decided not to ‘re-regulate the banking sector’?” And the follow-up question, if your answer is “yes” is: “If the Great Recession and the epidemic of bank fraud is not sufficient for you to reregulate the banking sector – what will it take?” Secretary Geithner and Chairman Bernanke state that the unregulated banking sector caused catastrophic losses and, but for extraordinary government intervention, would have caused the Second Great Depression. Effective banking regulation is essential to protect the public and honest banks. Both parties’ economic policies, however, are dominated by theoclassical economic dogma. Breaking the death grip of this criminogenic dogma on theory and policy is the economic profession’s most pressing need. Economists, and the politicians who find parroting their anti-regulatory policies so useful in raising campaign contributions, are the greatest threat to the economy.