By William K. Black

(cross-posted with Benzinga.com)

If you read this column you are familiar with our family rule that one can never compete with unintentional self-parody. The Justice Department is the latest exemplar of this rule. Joe Nocera’s March 25, 2011 column, “In Prison for a Taking a Liar Loan” discusses the case. Spoiler alert: Joe ends his column with a twist that is the thrust of my column so please read his column first.

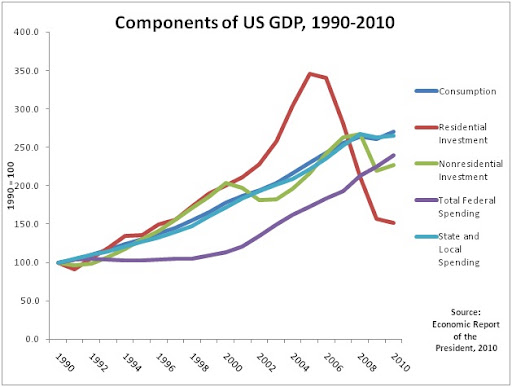

I have explained in prior columns some of the principal myths about “liar’s” loans. See particularly “How did a Relatively Small Number of Subprime Loans Cause a Record Crisis?” and “Lenders Put the Lies in ‘Liar’s’ Loans.” The answer to the question posed was that nonprime loans were a large portion of the residential housing finance market, roughly half of new mortgage originations by 2006 according to Credit Suisse’s estimate. Other estimates are that nonprime loans were over one-third of all new mortgage originations by 2006. Under either estimate nonprime lending caused an enormous increase in mortgage lending. Nonprime lending caused the “epidemic” of mortgage fraud that the FBI first publicly warned about in September 2004. Nonprime lending led to such a large increase in home purchasers that it hyper-inflated the financial bubble.

Credit Suisse found that by 2006, half of all new residential loan originations in the U.S. called “subprime” were also “liar’s” loans, i.e., they were made without verifying essential financial information about the borrower (typically income and employment). Most people assume that “subprime” and “alt a” (aka, “stated income” and “liar’s loan) were officially defined, mutually exclusive categories of loans. Both assumptions are false. There were multiple, inconsistent definitions of “subprime.” The confusion was deliberate. Nonprime lenders and sellers and purchasers of nonprime paper profited by systematically and dramatically overstating the credit quality of nonprime loans they owned.

Liar’s loans got that name because they were pervasively fraudulent. The fraud incidence in liar’s loans was often 80% or above. I have explained previously why, in the mortgage context, liar’s loans inherently produce intense adverse selection and that adverse selection causes such lending to have a negative expected value. (In plain English, this means that making liar’s loans is guaranteed to cause lenders severe losses.) This explains why honest home lenders do not make “liar’s” loans. For reasons I have explained, lenders that made material amounts of liar’s loans had to engage in accounting (and if they were publicly traded, securities) fraud. Entities that sold or held substantial amounts of liar’s loan paper also had to engage in accounting and securities fraud. Sellers could not disclose to their purchasers that the liar’s loans were pervasively fraudulent and would produce enormous losses. Holders of liar’s loan paper could not establish the loss reserves required by GAAP (and by the SEC) for the losses inherent in liar’s loans because the losses would have been so large that the firm holding the paper would have to report it was unprofitable and likely insolvent. I refer to the lenders that made significant numbers of liar’s loans as “lying lenders.”

Liar’s loans are optimal for only one group of lenders – those engaged in accounting control fraud. The four ingredients of the recipe for fraudulent CEOs of lenders to maximize the bank’s (fictional) short-term reported income and (real) longer-term losses are:

1. Rapid growth

2. Making loans at a premium yield even to the uncreditworthy

3. Extreme leverage

4. With grossly inadequate allowances for loan and lease losses (ALLL)

The officers that control the lenders that follow this recipe achieve what Akerlof & Romer aptly termed a “sure thing.” The recipe is mathematically guaranteed to produce record short-term income (until the bubble collapses) and, with modern executive compensation, make the officers wealthy. The lender fails (or is bailed out), but the controlling officers walk away rich. Akerlof & Romer’s title emphasized that dynamic – “Looting: the Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit.”

Liar’s loans were ideal ingredients for optimizing this recipe for maximizing fictional income and executive compensation. The two most obvious advantages were that competent underwriting takes time and costs money. Not underwriting, therefore, allowed fraudulent lenders to lend more cheaply (if one ignores the resultant, catastrophic losses) and more quickly. Not underwriting aided the first ingredient – it made rapid growth easier and, by reducing expenses, increased reported short-term income.

Liar’s loans also aided the second ingredient of the fraud recipe. Lending even to those who will often fail to repay the loan requires the bank to subvert normal underwriting and internal controls. Liar’s loans are the most elegant solution to subverting normal underwriting and internal controls. Liar’s loans, by definition, eviscerate essential underwriting and make it difficult for internal controls to operate effectively. (One could, of course, demand verification of income and employment of a sample of the liar’s loans – but lying lenders did not want to document that they knew their loans were pervasively fraudulent.) Lying lenders are able to grow rapidly and charge a premium yield to borrowers. Anyone can qualify for a liar’s loan – all it requires is fraud and the mortgage bankers own anti-fraud specialists (MARI) warned the industry in 2006 that “stated income” loans deserved to be called liar’s loans because they were “an open invitation to fraudsters.” Even a poor credit history could be overcome by enough fictional borrower income and fictional housing value. Millions of liar’s loans were made even to borrowers with credit histories so poor that the loans were considered subprime.

The Bright Shining Lies Underlying Liar’s Loans

Lying lenders found liar’s loans ideal for predation. Yield and growth are the keys that determine which types of loans maximize fictional accounting income. The fundamental attraction of liar’s loans was the premium yield. The higher yield, of course, was harmful to the borrower and no rational, informed borrower who could qualify for an underwritten loan at a lower interest rate should have taken out a liar’s loan. Liar’s loans were marketed and sold under a series of bright shining lies. The primary lie was that liar’s loans were really prime (“A”) loans that were underwritten under an alternative, equally effective means – hence the term “alt-a.” The alternative to traditional underwriting was to rely instead almost entirely on the borrower’s credit score – without verifying the borrower’s income, employment, etc. This lie implicitly claimed that “alt-a” borrowers were providing the lenders a free, premium yield unrelated to increased risk.

The bright shining lie was premised on four subsidiary lies. One, “alt-a” borrowers really had the same credit quality as other prime borrowers but could not verify their income. Two, the reason borrowers could not verify their incomes did not constitute a credit risk. Three, the borrowers actually had the income stated on the loan application. Four, a borrower’s credit score is an equally effective alternative means of underwriting credit risk to traditional underwriting (which verifies the borrower’s actual income, employment, etc.).

The typical bright shining lie story was the self-employed business person who could not credibly verify his own income. The story was not simply nonsense; it was obvious nonsense. The IRS has long had a form to cover this concern. The borrower signs it to authorize the IRS to release to the lender copies of the borrower’s federal income tax returns. Americans do not deliberately overstate their income on their tax returns because doing so would increase their taxes, so the tax return provides highly reliable information to the banker on the self-employed. The spread between prime and liar’s loans shrank over time (the opposite would have occurred if liar’s loans were not fraudulent and markets were efficient), but a liar’s loan was always substantially more costly to the borrower over the life of the loan. No honest self-employed borrower would opt to pay tens of thousands of dollars in additional interest rather than provide the IRS form and give the bank access to his tax returns. A credit score inherently cannot underwrite a borrower’s ability to repay a mortgage loan and it is an unreliable measure even of a borrower’s willingness to repay a jumbo mortgage loan. It is easy to game a credit score by taking out, and promptly repaying, a series of small loans and a borrower can readily fraudulently “borrow” another person’s higher credit score.

Why Borrowers took out Liar’s Loans

There are four obvious reasons why a borrower would pay the higher interest rate required to obtain a liar’s loan. One, the borrower did not have the income necessary to receive any mortgage loan. The loan officer and the loan broker knew the minimum incomes (though even the minimums were often negotiable). They would falsify the income or direct the borrower to falsify the income stated on the loan application. Normal underwriting easily detects and prevents this fraud – which is why credit losses on traditional residential mortgages were minimal for nearly 50 years. Fraudulent lenders designed liar’s loans to remove these underwriting protections against fraud. Their fraud-friendly design was so successful that their own industry anti-fraud experts (MARI) denounced their product as “an open invitation to fraudsters.” The officers controlling the lying lenders designed and implemented the perverse incentives that produced the intended “echo” fraud epidemics among loan brokers, loan officers, appraisers – and some borrowers. The combination of liar’s loans and the echo epidemics helped the controlling officers produce the first two ingredients of the lender fraud recipe – rapid growth at premium yields. The officers that controlled the lying lenders wanted to be able to make loans to the uncreditworthy – as long as they could do so at a premium yield. Liar’s loans made it easy to do both – and prevented the creation of an incriminating underwriting paper trail documenting that the lender knew the information on the loan application was false when it made the loan. The resultant deniability is implausible to anyone that understands fraud mechanisms, but it does fool the credulous.

Two, the borrowers would pay the higher interest rate if they had the requisite income but were hiding its existence from their current or prior spouse or the IRS. Do not make the mistake of believing that this situation represents minimal credit risk to the lender. A borrower who will lie to loved ones and the government (both of which are typically criminal acts) in order to keep from paying them legal obligations poses an exceptionally great credit risk to the lender. The borrower’s character is one of the most important determinants of credit risk.

Three, the borrowers could receive better loan terms if they inflated their income on the loan application. This could prompt borrowers to engage in fraud. Fraudulent borrowers could get larger loans at a lower interest rate if they made the debt-to-income ratio on the loan appear to be smaller by inflating their incomes. Borrower fraud of this nature obviously posed an enormous credit risk to the lender. The third and fourth categories of borrowers who would be willing to take liar’s loans illustrate the complexity of accounting control fraud. To understand these categories of borrowers one must understand the officers who controlled the lying lenders. The controlling officers wanted to make large loans, in enormous, growing volumes, at premium yields because doing so produced a “sure thing” of record (albeit fictional) short-term income and high bonuses.

The controlling officers, of course, have preferred to maximize the yield on liar’s loans but they did not have the power to do so. The controlling officers faced several tradeoffs. If they got honest information on the uncreditworthy lenders they could not grow rapidly by making loans at a premium yield to that group – and lending to that group was essential to their fraud strategy. In a reasonably competitive, mature industry like home lending a bank cannot grow rapidly and achieve premium yields by making enormous numbers of high quality loans. High quality borrowers typically can borrow from any bank at a low yield. A lender that tried to grow rapidly by making high quality residential loans would have to “buy market share” by lowering its yield. Its competitors would match the lower yields and the result would be that the home lenders active in that regional market would suffer materially lower reported income (reducing executive compensation). The implication of this first tradeoff (among growth, yield, and credit quality) was that the only sure way to grow rapidly and charge premium yields in a reasonably competitive, mature home loan market (ingredients one and two in the fraud recipe) is to make large numbers of loans to the uncreditworthy.

The other major tradeoff arose from the need to loan to the uncreditworthy. I have explained why this always requires the lender’s controlling officers to suborn the bank’s underwriting and internal and external controls in order to implement their strategy of accounting control fraud (what Akerlof & Romer aptly termed “looting”). Control frauds are so dangerous in large part because they are routinely able to suborn successfully these systems. Suborning underwriting and controls, however, requires a tradeoff. It inherently leaves the lender exceptionally vulnerable to internal and external frauds by parties other than the controlling officers. Fraud begets fraud. Eviscerating underwriting and controls makes the bank environment highly criminogenic and often kicks off an “echo” epidemic of fraud by others.

Strictly speaking, the controlling officers who are looting the bank through accounting fraud neither desire nor necessarily know in advance of the specific acts of secondary fraud by others. The CEO that is looting “his” bank would prefer not to share to the fraud gains with others, but this represents another tradeoff. The fraudulent bank CEO needs to incent large numbers of individuals to act perversely in order to accomplish the primary fraud that he is directing. He must unhinge effective underwriting and controls, so he must expose the bank to secondary internal and external fraud by others. Similarly, fraudulent bank CEOs frequently found it desirable to pay generous bonuses to their agents (i.e., loan officers and loan brokers) in order to incent them to make loans to the uncreditworthy and produce false loan applications and appraisals that would cause the loans to deceptively appear to be far less risky – which translates into far more valuable loans (which are a lender’s assets). Again, they traded much greater growth in loans with premium yields that falsely appeared to be of relatively low credit risk for loans that were, in reality, far more likely to be based on fraudulently inflated borrower income and appraised values and therefore far more likely to default and to cause larger losses upon default. The perverse incentive structures the officers controlling the lying lenders created for their employees and agents made it inevitable that liar’s loans would be pervasively fraudulent. The law allows us to hold the CEO’s who controlled the lying lenders criminally responsible for the predictable consequences of these perverse incentives.

Indeed, accounting control fraud is finance’s “weapon of choice” in much of the developed world because it is the superior solution to the tradeoff between the risk of being sanctioned for looting and the rewards from looting. Even the most powerful bank CEO faces a grave risk of being imprisoned if he sticks his hand in the till and steals $10,000. If, instead, he uses accounting control fraud to loot the bank of $50 million he has an excellent chance of never even being prosecuted. All he has to do is limit his means of converting bank assets to his personal benefit to seemingly normal executive compensation received because the bank “earned record profits” in the short-term.

The recipe for accounting fraud is a “sure thing” that will produce those (fictional) record profits and quickly make the CEO exceptionally wealthy. The record income, of course, will be blessed by a top tier audit firm. The recipe fraudulent U.S. bank CEOs use maximize short-term reported income and their compensation is attractive because it is a “sure thing” with minimal risk of prosecution, but it does represent a tradeoff. Fraudulent CEOs can convert a higher proportion of bank assets to their personal benefit (“fraud efficiency”) if they make themselves the direct beneficiary of the fraud. They can do so by stealing money from the vault, causing the bank to lend money to them that they do not repay, or causing the bank to lend money to them through a nominee (also called “straw man” or a “shill”). Indeed, the fact that most fraudulent U.S. bankers overwhelmingly loot “their” banks through accounting control fraud tells us that they still fear prosecution. In nations where the CEOs believe that they can loot directly with impunity they employ cruder frauds that achieve greater fraud efficiency.

I need to emphasize several words of caution about the concept of optimization, particularly when applied to very large corporations. Readers who have lived through conventional microeconomics and then worked in the real world know that the neo-classical claims of firm optimization in perfect competition are, to be gentle, misleading. Neo-classical economists’ assumptions about rationality fail descriptively and often fail to predict behavior. Anyone that has dealt with CEOs knows that ego, a desire for fame, a feeling of exceptionalism – they are not subject to the same rules as govern lesser persons – and a consuming drive for dominance can drive decisions. Criminology arose from sociology and psychology is our cousin. White-collar criminologists have long employed a non-ideological view of rationality. We have long-recognized that from the perspective of the fraudulent CEO, the economic and psychological aspects of their fraud schemes tend to be mutually reinforcing. It is the rare CEO who is exceptional (in a positive manner) relative to his peers. The “sure thing” aspect of accounting control fraud simultaneously makes mediocre or failing CEOs wealthy, famous, and powerful. Criminologists never expect perfect optimization. Perfect optimization never occurs in large organizations. Large organizations have various fiefdoms which may have variant professional cultures. Unfortunately, neither honest nor fraudulent CEOs require perfection to pursue (imperfectly) an overall banking strategy.

Lying lenders that sold their liar’s loans found other aspects of these loans optimal. The best loan originations from the perspective of the secondary market had four characteristics: a premium yield, on a larger loan, loan structures that would postpone as many early defaults as possible (e.g., “teaser” initial interest rates so low that they failed even to pay the interest – producing negative amortization), and the appearance of relatively low credit risk. Liar’s loans were superb devices for obtaining, simultaneously, these four (sometimes inconsistent) objectives. The loan brokers commonly inflated seriously the borrowers’ real income and knew that this would produce very high early period defaults (EPDs) unless the borrowers’ payments were reduced substantially. The loan broker could structure the loan to employ an initial, far lower, “teaser” rate in order to greatly reduce EPDs. The loan brokers and loan officers frequently created a “Gresham’s” dynamic (bad ethics drives good ethics out of the market) to induce an echo epidemic of appraisal fraud. By inflating the appraisal and the borrower’s income, the loan officers and brokers were able to maximize their fees and bring in huge loan volume. Inflating the borrowers’ income lowered the reported debt-to-income ratio and inflating the appraisal lowered the reported loan-to-value (LTV) ratio. The two forms of fraud made it appear to those purchasing liar’s loans that the loans were lower risk. By structuring the loans to delay the inevitable defaults the loan brokers and officers were able to reduce EPDs and allow more time to refinance the liar’s loans. Collectively, these characteristics led to premium prices being paid by those purchasing liar’s loans for the secondary market. The officers controlling the lying lenders structured the perverse financial incentives they paid to the loan brokers and officers – and made it clear to them by approving liar’s loans and paying the brokers and officers large bonuses for making fraudulent loans sure to default frequently – that they would not effectively kick the tires to prevent the endemic fraud the criminogenic incentives were certain to produce. Liar’s loans were the financial variant of “don’t ask; don’t tell.”

Four, some borrowers who took out liar’s loans were relatively low risk, even prime, borrowers. The ideal mortgage loan for an accounting control fraud is a very low risk loan paying a premium yield. (Recall that this was the lying lenders’ bright shining lie about liar’s loans.) Theoclassical economists asserted that it was impossible to make loans having both characteristics. Such loans would not occur in efficient financial markets. They can occur, however, under predation. Predatory lenders take advantage of information asymmetries to induce lower-risk borrowers to borrow at excessive yields. The information asymmetry is greatest when lending to the financially unsophisticated and those that cannot comprehend the loan terms because they are not literate in the language used in the loan documents. Those asymmetries, statistically, are more likely to be large among Latinos and African-Americans. Some borrowers, therefore, could have provided “free” premium yields to the lying lenders. However, one should be cautious about assuming that the premium yield was a “free” premium even in cases of predation. Loan brokers and officers were operating under such perverse incentives (created by the lying lenders), that they are likely to have exploited the information asymmetries by encouraging financially unsophisticated clients to purchase homes they could not afford under the premises/promises that the loan could always be refinanced and home prices always rose. The more expensive the home being purchased, the larger the loan, and the greater the fee the loan brokers and officers would receive. But this also meant that the victims of predation were being abused in multiple ways and put into homes and loans they could not afford – which caused severe credit risk and meant the purported yield premium was not remotely large enough to compensate the bank for the credit risk of making the liar’s loan.

Which (finally) brings us back to Nocera’s Column

The twist in Joe Nocera’s column is that the borrower on a liar’s loan from Countrywide is in prison for lying on a loan product that Countrywide’s controlling officers structured knowing that it would produce endemic fraudulent applications. Countrywide’s controlling officers structured their liar’s loans in this manner to facilitate their vastly greater looting of Countrywide’s creditors and shareholders. The prosecution of Countrywide borrowers for fraudulent liar’s loan applications is the modern variant of the old joke.

“What does chutzpah mean?”

“A son killed his parents and asked the court for mercy because he was an orphan.”

Nocera’s story is also a wonderful illustration of how insane our lack of prioritization is in prosecuting the lying lenders that drove the “epidemic” of mortgage fraud that hyper-inflated the financial bubble and caused our financial crisis and the Great Recession. No senior officer of the major nonprime lenders that caused the catastrophe has been prosecuted. (One will be, but even he is a special case because the investigation and indictment were triggered by an alleged effort to defraud the TARP program.) The contrast to the S&L debacle, where we obtained over 1000 felony convictions in “major” cases and ensured that the most culpable, most elite frauds would be prosecuted by creating the “Top 100” list of fraudulent S&Ls is stark and should prompt public outrage. The FBI deserves great credit for warning about the “epidemic” of mortgage fraud in its September 2004 testimony – over six-and-a-half years ago – and predicting that it would cause a financial crisis if it were not contained. Countrywide went heavily into liar’s loans after that warning and went even more heavily after MARI denounced the loans in 2006 as “open invitations to fraudsters.” The FBI can place undercover agents in banks without even changing their resumes or names. If it had sent undercover agents into the ten largest lying lenders in 2004 it could have prevented the Great Recession. Banks engaged in accounting control frauds operate in ways designed to superficially mimic honest lenders, but there are clear markers of fraud that a special agent who understands fraud mechanisms would be able to spot within days. Honest lenders do not make liar’s loans, do not inflate appraisals, do not suborn their underwriting staff and internal and external controls, do not create perverse incentives for loan brokers and officers and other corporate officers, do not forge borrowers’ signatures, and do not suggest or provide false information on loan applications. Lying lenders and/or their agents routinely did each of these things. The IRS, in a situation in which we prosecute none of the lying lenders’ controlling officers and only prosecute around 1000 of the roughly one million annual cases of mortgage fraud – a strategy that guarantees failure – used a wired undercover special agent to investigate one of those individual frauds. It did so while giving a pass to Countrywide’s CEO, the exemplar of “bankruptcy for profit.” Countrywide was shocked, shocked to hear that there was lying going on in its liar’s loans. The loan broker (a confessed fraud) suggested the fraudulent statement of income on the loan application and may have forged the borrower’s name on the application. (Both practices were common because lying lenders, including Countrywide, structured their bonuses to loan brokers to ensure that the brokers could make very large amounts of money by fraudulently inflating the borrower’s income and appraised value of the home.

Nocera’s story demonstrates that the Justice Department has mastered the art of unintentional self-parody. Attorney General Holder should resign as a matter of principle and the administration should find a real AG. I suggest a novel choice that the Republicans could not block: Sol Wisenberg. Sol was chief of the Financial Institution and Health Care Fraud Unit in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Texas, where he successfully brought one of the “Top 100” S&L fraud cases. He later became a senior prosecutor in Ken Starr’s Office of Independent Counsel (conducting a famous deposition of President Clinton). Sol left the Federalist Society because it wasn’t conservative enough for his tastes. The point is that prosecuting elite white-collar criminals isn’t a political or ideological act. It is essential to our democracy and our economy.

I’ve seen Sol train FBI agents and prosecutors how to investigate and try sophisticated financial frauds. I’ve seen him prosecute in court. We share the same fundamental attitude. We don’t care about the politics, power, or ideology of the folks we investigate. We don’t scream. We don’t think bankers are crooks by definition. We know that if cheaters prosper markets become perverse. We try to make sure that cheaters don’t prosper. President Obama, please start to use the “f” word – call the frauds “frauds” and demand accountability. Did you read Nocera’s story? What did you order Attorney General Holder to do in response? I urge the next reporters who interview the President to ask both of these questions.