In my last post I asked this same question about the House Budget Committee. As my readers saw in that one, the attempts at deficit reduction leading to budget balance were so severe that they implied that if the House budget were followed, and if the economy did not collapse before the decade projection period ended due to a collapse of aggregate demand, then private sector deficits would be produced in every year from 2017 – 2025. In addition, since the budget provided for severe cuts to federal spending designed to benefit poor people and the middle class, it was likely that the private losses from this budget would be concentrated on the people who can least well absorb them.

In this post, I’ll review the sectoral financial balances implications of the White House/OMB projections to see how they compare to those of the House Budget Committee. I’ll begin by repeating the explanation of sectoral financial balances basics I included in my earlier post.

The Sector Financial Balances (SFB) model is an accounting identity, and these are always true by definition alone. The SFB model says:

Domestic Private Balance + Domestic Government Balance + Foreign Balance = 0.

The terms refer to balances of flows of financial assets among the three sectors of the economy in any specified period of time. Why must there be flows? Because the three sectors trade financial assets with one another. So, the equation says that the sum of all the balances of flows for the three sectors of the economy is zero, because, since there’s only so much in assets traded in any time period, the positive balance(s) of one or more sectors relative to the others must be matched by the negative balance(s) of the other two sectors.

So, for example, when the annual domestic private sector balance is positive, more financial assets are flowing to that sector, taken as a whole, than it is sending to the other two sectors.

Similarly, when the annual foreign sector balance is positive, more financial assets are being sent to that sector than it is sending to the other two sectors.

And when the annual government sector balance is positive, then it is getting more in financial assets from the other two sectors combined than it is sending to them.

Conversely, when the private sector balance is negative, the private sector is sending more to the other two sectors than it is getting from them, and so on for each of the other two sectors.

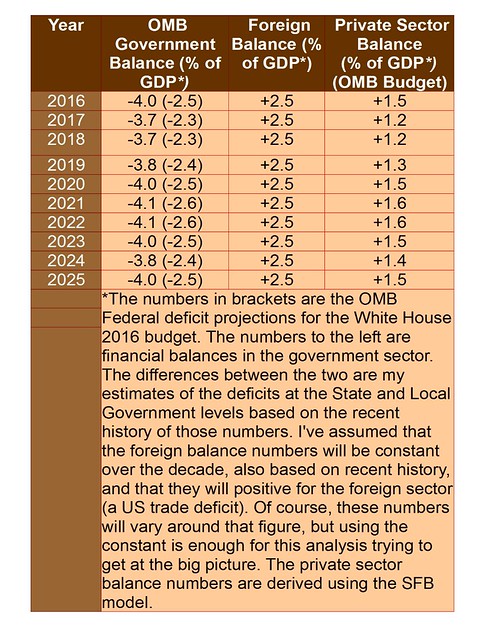

Now let’s apply this to the White House/OMB Federal budget projections from 2016 – 2025, in Table One, just below.

Table One: Sector Financial Balance Projections (from OMB) 2016 – 2025

To place these gains in perspective, we need to recognize that the mean private sector surplus in the period 2009 – 2014 was approximately 7.2% of GDP for that 6 year post-crash period. But the Government deficit spending injections resulting in those surpluses were not great enough to create the level of aggregate demand necessary to produce a robust economy with rapid job creation, full employment and widespread prosperity for the 99%.

Instead, these private sector surpluses have only been enough to end the recession and produce a slowly growing stagnant economy, whose rewards are vast for the already wealthy and for large corporations, but are miniscule, or non-existent, for everyone else. So, ask yourselves what the projected small Government deficits over the decade 2016-2025 resulting in mean private sector surpluses of approximately 1.4% of GDP annually are likely to do by way of producing the aggregate demand needed to create full employment and shared prosperity? Not very much I’m afraid.

We know very well that our nation’s economy is structured so that some parts of the foreign sector and some parts of the private sector have sufficient economic and political power to direct financial flows from outside and inside their sectors disproportionately into their coffers. So, this means that the sub-sectors with lesser economic and political power will suffer the burden of the losses, as they have been doing for the past nearly 40 years.

Which sub-sectors will grab what aggregate savings are produced are identified in the House Budget post. The Government can counter the maldistributive impact of the current economic institutional structure, at least in part, by targeting its spending and tax relief on the sub-sectors that need it most. But the OMB budget doesn’t do much of that.

So, the implications of its budget are that small and large companies not in the sub-sectors that have the power to channel gains to themselves, and also households in the 99%, will still get poorer and poorer, year after year, if the OMB projections should be realized, though this won’t happen quite as rapidly as it would under the House Budget Committee’s plan. It’s a case of boiling the frog more slowly than the Republican version, but its planned deficit spending is far too small and poorly targeted to create satisfaction with the economy. In other words, we have austerity lite, as opposed to the militant austerity of the House Budget effort.

Eventually, unless there’s a credit bubble providing money and corresponding debt liabilities to these sub-sectors, consumer demand will gradually decrease until it finally collapses because net financial assets cannot be drawn upon to maintain it. In other words, the implications of the OMB budget projections are another economic crash during the coming decade probably sooner rather than later, but probably later than we will get with the House Republican Budget.

What can delay this process leading to collapse? It will be the failure of the OMB deficit projections, because they don’t accurately project the effects of the automatic stabilizers reacting to the very small private sector gains implicit in the OMB plan.

The automatic increases in government deficit spending caused by rising unemployment insurance payments, food stamp spending, early retirements and disability spending will create larger deficits than OMB projects, though probably not until after the elections of 2016. At that time, deficit spending will be greater than planned, and it will ease the pressure on the private sector from the small private sector surpluses because, one more time, government deficits in the realm of automatic stabilizer spending mean private sector surpluses and gains in consumer demand that will boost the economy.

However, the “accidental deficits” produced will not be big enough, nor targeted well enough to prevent continuing stagnation. In my next post, I’ll look at the Congressional (CPC) budget and see if the CPC has yet learned the lesson that projections that don’t take sectoral financial balances into account project private sector results that are far from consistent with what is necessary for a robust and just economy.

21 responses to “When Will the White House and OMB Ever Learn About Sector Financial Balances?”