Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Monthly Archives: February 2012

Response to Comments on Blog #35: Thirlwall’s Law

Sorry for being late. There were really only two issuesraised (ignoring the comment about MMR vs MMT—which I’m not going to addresshere).

The first concerned the orthodox belief that trade dependson comparative advantage: Italy specializes in wine because of its climate andsoil. In the case of agriculture in the old days, there isn’t too much doubtabout that—it was hard to grow grapes at the North Pole, so Santa tradeddelivery services for products made in southern climes. But once we move beyondagriculture, and after we’ve invented greenhouses and the like, there is muchless truth in this. In manufacturing, a factory can be set up anywhere in theworld, often in a few weeks, and it takes a couple more weeks to train theworkers. And out in the real world what we find is that much of the trade infinished goods is actually between “equals”: Italy sends Fiats to Germany andGermany sends VWs to Italy. Tastes or preferences, styles, desire to be different,brand loyalty, and all that matters much more.

The second is more important and concerns the belief thateconomic growth is balance-of-payments constrained, as described by TonyThirwall’s “Law”. As Neil “Ramanan” Wilson Jargued: “There have been some suggestions that Thirlwall’s law stops thegovernment expanding domestic policy and will cause ‘twin deficits’ problems(increased government and external deficits). But why would that apply togovernment and not private expansion? Thirlwall’s law appears to have a fairamount of empirical data behind it, but is that curve fitting? In other wordsdoes the Law appear true because nobody dare do the domestic expansion in thecorrect fashion necessary to test the underlying assumptions on which it is based.”

To simplify and summarize: A country like the US that has ahigh propensity to import will tend to run a trade deficit if we grow fasterthan our neighbors who have low propensities to import. We will then run out offoreign reserves quickly so will be constrained to the extent that ourneighbors won’t take our currency in exchange. Thus, our growth will beconstrained—it needs to be slower than that of our neighbors.

To be sure, Thirlwall would throw in lots of caveats thatare usually ignored by those who wave his “Law” about. Not all growth has thesame implications for the trade balance. Income distribution matters forimports—so it depends on who benefits from the growth. We could target ourgrowth to areas that make us more competitive internationally—increasingexports. If we do grow faster than our neighbors, their demand for our currency(to invest in the US, for example, to share in the bounteous growth) might growas fast as our current account surplus. If we float the currency, theconstraint is softened since a trade deficit might cause the exchange rate tofall and thereby increase exports and reduce imports. And we can change policyto encourage exports and restrict imports, or to encourage “capital” inflows(demand for our currency to buy assets). So for all these reasons, there is nosimple “Law”.

Neil also raises an important point usually overlooked bythose who advocate the “Law”: the evidence in favor of a constraint probablyhas more to do with policy overreaction than to any real constraint.Governments react to a current account deficit by tightening the fiscal andmonetary policy screws, trying to raise unemployment and slow growth. That is apolicy choice. Except for those nations that choose to peg their currencies (oradopt foreign currencies—as Greece did), it is almost always going to be a badpolicy. Indeed, pegging the exchange rate is a bad policy because it usuallyforces government to give up policy space. Unemployment is the normal price ofpegging—and it is pegging and the reaction to a current account deficit that thenmakes Thirlwall’s Law “bite”.

Let us say that a country does not impose the “Law” onitself, refusing to adopt austerity when a trade deficit appears. What happens?At a constant (but not pegged—this is a little mental experiment) exchangerate, for its current account to increase, there must be a demand for itscurrency so that its capital account surplus rises by the same amount. In otherwords, there are two sides to the coin, and as foreigners demand the currency,a capital account surplus is created, and as the domestic population demandsthe imports, a current account deficit is created. We cannot split the coin inhalf to blame one side or the other.

Let us say that the rest of the world (ROW) will not allowthat to happen—the ROW will accept the currency only if it depreciates. OK,then, the currency falls in value to find holders of the currency given acurrent account deficit. And as the currency falls, exports might rise a bit,and imports fall a bit. But let us say that this will not restore trade“balance” (recall from my earlier blog however that “balance” is a misleadingword—the balances always balance!). As the currency depreciates, the terms oftrade turn against the country. In other words, it gives up more currency toget the same basket of imports.

(Yet in real terms as a current account deficit is created,the country gives fewer exports to get imports! How ironic: the real terms oftrade move in the favor of a trade deficit nation. Exports are the cost,imports are the benefit.)

If you are an OZ that imports oil and finished manufactures,a depreciating A$ raises the A$ cost of much of what you buy. And as BillMitchell argues, the swings of the A$ are historically large and do lead to verylarge fluctuations of the domestic purchasing power. But so long as Australiakept its commitment to full employment, it tolerated these swings withoutimposing austerity. Policymakers preferred to use their domestic policy spaceto maintain growth with (nearly) full employment. So Oz consumers would remainemployed and would substitute out of expensive imports as best they could. Andthey’d probably have to reduce overall consumption when the Oz Dollar fell. Thosewho follow MMT and Functional Finance believe that is the best policy.

Should a nation like Oz adopt other policy in response to atrade deficit? Bill often uses the example of auto manufacture. Oz might havetried to keep out Japanese autos in order to promote Oz auto production. Billhas argued this makes little sense, and would cost Australian consumersdearly—both in terms of loss of choice but also in terms of a policy ofdevoting substantial real resources to produce autos at what might be a scalefar too small to achieve economies of scale. I have no dog in this hunt and noparticular opinion on the issue of Oz auto production. But Bill’s argumentmakes sense to me as a general statement. It is also related to the comparativeadvantage argument briefly discussed above. If you can import high quality andlow cost products from abroad, it may not make sense to use government policyto block the imports and to subsidies domestic production. Remember: importsare a benefit, exports a cost, in real terms. Of course that is only true ifyou have a commitment to full employment. So if auto jobs are lost governmentmust ensure alternative employment.

The immediate response always is: “but auto jobs are good;nonmanufacturing jobs are bad”. Only one who has never worked in a factorycould literally believe this. (Full disclosure: I worked in a soup factory andwhile I liked the pay, I hated the work.) What most mean is that factory jobspay well, many service sector jobs don’t.

The solution—of course!—is to make the service sector paymore. I am always amazed at the lengths to which people will go to offer“crazily improbable” (in Keynes’s words) solutions rather than looking to theobvious.

To be clear, I have nothing against using domestic policy ina strategic manner—to target areas for expansion. All economies area alwaysplanned. The questions are: by whom and for whom. But responding to a tradedeficit by imposing austerity simply imposes a “Thirlwall’s Law” growthconstraint unnecessarily.

There are many other issues related to imports, exports, andexchange rates—we’ll return to some of them in the remainder of the Primer.

A Dimon Repeatedly in the Rough who Demands Winter Rules (aka Preferred Lies)

By William K. Black

(Cross-posted from Benzinga.com)

Golf is one of the sports associated with the CEOs of big banks, so it is not surprising that Jamie Dimon is expert at seeking to invoke Winter Rules whenever JPMorganChase (NYSE: JPM) finds that its actions have placed it in an unfavorable lie.

Golfers know that they cannot unilaterally invoke Winter Rules – only the folks in charge of the course can put Winter Rules in effect. When Winter Rules are put in effect the golfer can improve his lies by placing his ball in a preferred lie.

A New York Times investigation by Edward Wyatt documented the depth of the rot at the SEC in a February 3, 2012 article entitled “S.E.C. is Avoiding Tough Sanctions for Large Banks.”

“JPMorganChase, for example, has settled six fraud cases in the last 13 years, including one with a $228 million settlement last summer, but it has obtained at least 22 waivers, in part by arguing that it has “a strong record of compliance with securities laws.””

SEC investigations have found that JPMorganChase is a serial violator of the securities laws. The bank gets caught, promises to clean up its act, gets fined, signs a typically useless consent decree that has no admissions, creates no precedent, and undercuts deterrence, and gets waived out of the few detriments there are to banks with records of serial SEC staff findings of violations.

JPMorganChase exemplifies this pattern of the SEC winking at serial fraud by the systemically dangerous institutions (SDIs). The SEC routinely allows the SDIs to operate under Winter Rules and the SDIs routinely and repeatedly employ preferred lies.

But the metaphor is inexact for three reasons. First, Winter Rules are not supposed to be routinely available. They are reserved for unusual circumstances where the course is unusually unplayable due to weather. Second, Winter Rules are available due to problems with the course not caused by the player. Third, when Winter Rules are invoked by the golf course the course posts that information publicly and Winter Rules are available to all players rather than to a subset, i.e., the wealthiest players.

Consider what the world would be like if we had a “three strikes law” for corporations. Assume that the corporations were only assessed a “strike” if the violations were attributable to the actions of a senior officer. Assume further that the SEC and the Department of Justice (DOJ) actually brought actions against the SDIs and required admissions of violations of the law in settlements and pleas. The SDIs would have been dissolved (the equivalent of being sent away for life) decades ago.

Consider the chutzpah of JPMorganChase claiming “a strong record of compliance with securities laws” after SEC staff investigations found six violations in 13 years. But that kind of arrogance and indifference to complying with the law is inevitable under an SEC regime that allows the SDIs to play by Winter Rules. “Improved lies” captures perfectly the perverse incentives that the SEC has created.

The CEOs of SDIs who know that they can commit fraud with effective impunity (the SEC fines are typically chump change from the SDIs’ standpoint) develop a belief in their divine right to transcend the law and conventional morality. Jamie Dimon captures the mindset that Nietzche celebrated for the Superman. Dimon extends the logic of transcendence to its ultimate, absurd, extreme. He is enraged that the CEOs running the SDIs have been criticized. It turns out that the SDIs’ CEOs are sensitive types. Nobody exemplifies this Rich White Whine motif better than Dimon.

“I’ve disagreed right from the beginning of this blanket blame of all banks,” Dimon said in an interview with Charlie Gasparino of the Fox Business Network Tuesday. “I don’t like that. I think that’s just a form of discrimination that should be stopped.”

The interview was taped shortly before Dimon left for the World Economic Forum summit in Davos, Switzerland, where Dimon said he will be speaking with other attendees about financial regulation. At last year’s Davos summit, Dimon made similar remarks pushing back against the vilification of the banking industry, calling it “a really unproductive and unfair way of treating people.”

No serious critic has a “blanket blame of all banks.” The blame is focused on SDIs, particularly SDIs like JPMorganChase that investigations find engaged in recurrent fraud, yet were treated to Winter Rules because they were SDIs. These SDIs are not only the bane of the world economy; they are the bane of honest banks.

Dimon has also reached the logical, albeit absurd, conclusion about the legitimacy of investigating JPMorganChase. He is tired of the investigations finding fraud, so he has decided, in the context of the settlement negotiations of the widespread foreclosure fraud by five large mortgage servicers including JPMorganChase, to offer a settlement in return for prohibiting the government from investigating his banks’ mortgage origination and foreclosure fraud.

When news reports claimed that the federal government was reducing its disgraceful offer of widespread impunity from investigation and prosecution, Dimon responded that it was likely that JPMorganChase would not enter into a settlement that did not have a broad prohibition on investigating JPMorganChase’s frauds.

“The new unit “has a pretty good chance of derailing it,” JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon told CNBC on Thursday, referring to the settlement. JPMorgan is one of the five banks involved in those negotiations.”

Dimon is the face and mindset of crony capitalism. It is long past time for the SEC to end selective Winter Rules and Preferred Lies for the SDIs.

Bill Black is the author of The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One and is an associate professor of economics and law at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He spent years working on regulatory policy and fraud prevention as Executive Director of the Institute for Fraud Prevention, Litigation Director of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and Deputy Director of the National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery and Enforcement, among other positions.

Bill writes a column for Benzinga every Monday. His other academic articles, congressional testimony, and musings about the financial crisis can be found at his Social Science Research Network author page and at the blog

Follow him on Twitter: @WilliamKBlack

Comments Off on A Dimon Repeatedly in the Rough who Demands Winter Rules (aka Preferred Lies)

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged fraud, jamie dimon, jp morgan chase, SEC avoiding tough sanctions, William K. Black

Alternative Fiscal Policies: Why the Job Guarantee is Superior (Wonkish)

A few weeks ago I called for a technocratic debate on the merits of the JG, relative to other fiscal policies. A number of bloggers took the charge but the debate was not immune to ideological biases, which proved the starting point of my piece that one cannot separate fact from theory or ideology (and by ideology I do not mean the derogatory use of the word, but that which signifies ‘ontology’ or a ‘world view’). What I didn’t expect is for friends and sympathizers to resurrect one particularly invidious charge we have long heard from MMT deniers, namely that MMT is pushing authoritarian policies.

Oh, boy. How did we even get here? I thought this was going to be a technocratic debate.

Greece and the Rape by the Rentiers

Here’s the draft of the supposed agreement to “sort out” the Greek debt problem once and for all. According to Bloomberg, here are the essentials:

- Greece’s 2012 GDP will shrink by as much as 5%.

- Greece is expected to return to growth in 2013.

- Greece will cut 15,000 state jobs in 2012.

- Minimum wage will be cut by 20 percent.

- There will be no increase to sales tax.

- The government will cut medicine spending from 1.9% to 1.5% and merge all auxiliary pension funds.

- It will also sell stakes in six companies—in particular, energy companies and refineries.

Of course, the current thrust of fiscal policy will almost certainly guarantee that there still will be a default, involuntary or otherwise, in spite of this agreement. If you don’t have a mechanism to allow growth, then how can the Greeks service their debt, even with the reduced debt burden?

Perhaps that’s the idea. Make the deal so miserable for the Greek people that the Spanish, Portuguese, Irish and Italians don’t even begin to think of trying to get a similar haircut on their debt.

Certainly, the deficit reduction won’t come. It can’t when you deflate a rapidly declining economy into the ground. Common sense suggests that a drop in private income flows while private debt loads are high is an invitation to debt defaults and widespread insolvencies.

Even with all of the concessions, the euro bosses have not officially signed off on the agreement:

* Finance ministers of the 17-nation euro zone arriving for talks in Brussels warned there would be no immediate green light for the rescue package and said Athens must prove itself first.

* “It’s up to the Greek government to provide concrete actions through legislation and other actions to convince its European partners that a second program can be made to work,” EU Economic and Monetary Affairs Commissioner Olli Rehn said.

* German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, whose country is Europe’s biggest paymaster, told reporters: “You don’t need to wait around because there will be no decision (tonight).”

* Greek Finance Minister Evangelos Venizelos flew to Brussels after all-night talks involving Prime Minister Lucas Papademos, leaders of the three coalition parties and chief EU and IMF inspectors left one sensitive issue – pension cuts – unresolved.

It is also worth pointing out that Greece’s pension payments on a per capita basis are amongst the lowest in Europe. Still, apparently, this plunder hasn’t gone far enough The Greek people must feel like Sabine Women right now.

Game, set and match to the Troika.

While we’re at it, let’s address this “Greeks as tax cheats” canard once and for all. Greece’s tax revenue from VAT collapsed by 18.7pc in January from a year earlier. As Ambrose Evans Pritchard noted:

“Nobody can seriously blame tax evasion for this. It has happened because 60,000 small firms and family businesses have gone bankrupt since the summer.

The VAT rate for food and drink rose from 13pc to 23pc in September to comply with EU-IMF Troika demands. The revenue effect has been overwhelmed by the contraction of the economy.

Overall tax receipts fell 7pc year-on-year.”

We’re one step closer to ensuring that the birthplace of democracy becomes a form of national indentured servitude. That is of course, unless Greece regains some modicum of self-respect and tells the Troika to take a hike and leaves the euro zone.

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Tagged euro crisis, euro exit, greek rescue package, Marshall Auerback, rentier class, troika

William K. Black on Financial Fraud

William K. Black talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about financial fraud, starting with the Savings and Loan debacle up through the current financial crisis. Black explains how bank executives can use fraudulent loans to inflate the size of their bank in order to justify large compensation packages. He argues that “liar loans” were a major part of the crisis and that policy changes made it easy to generate such loans without criminal repercussions.

Comments Off on William K. Black on Financial Fraud

Posted in William K. Black

Tagged Control Fraud, econtalk, liar loans

The Elephant in the Room is Spain, Not Italy

Another day andthe markets remain fixated on whether Greece comes to a “voluntary” arrangementwith its creditors. The key word is“voluntary” because the myth of “voluntary compliance has to be sustained sothat those deadly credit default swaps avoid being triggered.

But let’s faceit: Greece is a pimple. If the rest of the euro zone could cut itlose with a minimum of systemic risk, Athens would have long gone the way ofTroy. The real issue is whether thecredit default swaps trigger such a huge mess with the counterparties that itcreates renewed systemic stress which more than offsets the benefits to theholders of the CDSs.

The moreinteresting question is: suppose Greece finally does get a deal? Irealize everybody says it is a “one-off”, but do you really think theIrish, Portuguese, or even the Spanish and Italians will go along with that,particularly if (as is likely) they continue to experience double digitunemployment and minimal growth?

Now you could argue thatPortugal and Ireland, like Greece, are but small components of the EuropeanUnion and could well be covered in one form or another via the existingbackstops established over the last several months, notably the EuropeanFinancial Stability Fund (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism(ESM).

But you can’t say this aboutSpain, which remains the real elephant in the room – not Italy – even thoughSpain’s borrowing costs remain lower than Italy’s. This is perverse.

Though Italy has a highsovereign debt, it has a low private debt (the product of years of high budgetdeficits, but that’s the story for another blog). Italy has a fiscal deficitthat is low relative to most economies today. It already has a primary surplus.The greater than expected past expansion of the ESCB and the current ongoingLTROs are likely to absorb panic and forced selling of Italian debt. TheItalian 10-year yield could fall back below 5% (having already fallen from the 7%plus levels, pertaining a mere 6 weeks ago).

In theory, this rally in bond yields should lead to a reassessment of thegravity of the Italian problem and therefore the European sovereign debt andbanking problem. That could be positive for equity markets and, indeed, hasbeen so since the start of the year.

But does Spain truly deserve theborrowing advantage it now has in relation to Italy? Its 10-year bonds are yielding some 60 basispoints lower. True, its sovereign debt to GDP ratio is low at about 75%, but partof its enormous private debt will almost certainly have to be “socialized.” Moreover, Spain has virtually the highestnon-financial private debt-to-GDP ratio of all the major economies. Its ratio is almost twice that of Italy’s. Itsfiscal deficit last year was probably higher than the official estimates, closeto 9% of GDP (the previous Socialist government routinely lied about itsfigures – in fact, no country, not even the US, has lied more extensively aboutthe condition of its banks. Spain, relative to GDP, has the largestshadow real estate inventory in the world, with the possible exception ofChina, which probably doesn’t even have a reliable second or third set ofbooks).

Let’s be clear about onething: this is not a tale of Mediterranean“profligacy”, as least as far as public spending was concerned. Anybody looking at Spain through a sensiblefinancial balances framework in the mid-2000s would have observed that theprivate sector was being squeezed badly by the fiscal drag. The externalposition was in deficit (current account) which means the public and externalbalances were draining growth from the economy. Yet it still boomed up into theonset of the crisis. How did that happen?

The profligates were all in theprivate sector, although you could readily argue that the government’s“responsible” fiscal policy created the conditions for a private sector debtbinge. Prior to 2008, the Spanisheconomy was held out as the darling of Europe however the reality was quitedifferent. The country was running budget surpluses by 2005 and foreigninvestment was booming. Most of this investment went into construction whichwas stimulated by a massive real estate boom.

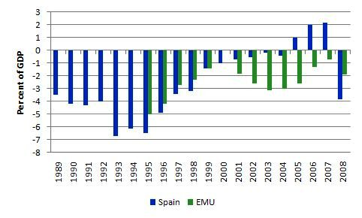

A few years ago, using data fromData from the Banco de España (central bank) Bill Mitchell graphed the nationalbudget deficit as a percentage of GDP for Spain and the EMU overall from 1989to 2008 (data for the EMU clearly didn’t start until 1995). As Mitchell notes,one can observe the tightening of fiscal positions as the Growth and StabilityPact provisions were forced on the EMU nations:

Consistent with a tighteningfiscal position leading to surpluses in 2005, the only way that this boom couldcontinue was for the private sector to go increasingly into debt.That is exactly what happened and because the property boom was so large thedebt levels were also very high – average household debt tripled. And that, incontrast to Italy, is the core problem with which Spain is dealing today to asubstantially greater degree than Italy. So it’s wrong to lump the two together interchangeably as the marketshave been doing. Paella and pasta don’tmix well together.

Okay, but that was the previousZapatero Administration. Now we supposedly have a new “responsible” conservativegovernment that promises to carry out the same policies even moreresolutely. And look how successfulthey’ve been: Spain’s joblessclaims shot up a further 4% in January from December to 4.59 million, a signthat the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy is still shedding jobs at a recordrate. All sectors posted more claims but the rise was sharpest for services at5.1%. In construction, weighed down by a four-year property slump, the numberof residents registered as job seekers rose 2.1%. Compared with the same perioda year ago, overall claims rose 8%. GDPcontracted 0.3%.

Okay,“give them time”, argue the defenders of the new government. And, if the Rajoy Administration was trulyembarking on a new policy course, that would be a fair comment. Unfortunately, this government has signed onto even tighter fiscal policy rules. Somehowthey are expected to suck demand out of their economies through tax increasesand spending cuts, but when the slower growth that results in means the targetfor deficit reduction is not met, the Spanish, like their Greek, Irish,Portuguese and Italian counterparts, will be punished for it.

Eventhe Rajoy Administration implicitly appears to recognize this danger, as it isalready moving the goalposts in regard to its spending cuts targets as apercentage of GDP. Unfortunately, theyblame this on external circumstances beyond their control. To the extent thatthey agree to submit themselves to rules which were routinely disobeyed by theGermans and French during the EMU’s inception, that is true, although theSpanish government refuses to acknowledge that their resolute tightening fiscalpolicy ex ante might well have something to do with the fact that Spain’seconomy continues to deflate into the ground ex post. Remember, thehistory of the Stability and Growth Pact has long demonstrated that thesenonsensical rules are already impossible to keep within during a significantdownturn. And now the new Spanish government wants to tighten them even furtherand invoke pro-cyclical fiscal reactions earlier.

This, at a time when the nationalunemployment rate is approaching 23%, and the youth unemployment rate (25 yearsor younger) is at 49%, according to the latest Eurostat data.

Sonearly 50 per cent of willing workers under the age of 25 in Spain are withoutwork and will remain like that for years to come. That will damage productivitygrowth for the next decade or more. It is an indication that the monetarysystem has failed and attempting to reinforce those failures with moreausterity will only make matters worse. The new government’s proposed fiscal policy “reforms” areparticularly toxic policy mixture for Spain.

Of course, the ongoing threat ofa disorderly default in Greece also remains a potentially dangerous areaif it is not contained by the ECB’s actions. But it’s more interesting to see what happens as the magnitude ofSpain’s problems become more apparent. Will the troika tell Spain that a Greek style70% haircut is not in the cards? Willthey try to suggest that the government is rife with corruption, that thecountry is chock-a-block full of scoff-laws and tax evaders, and that theefficient Germans would do a much better job of collecting taxes?

Spain is still a relatively youngdemocracy. The transition began a mere37 years ago when Francisco Franco died in 1975, but there was an attemptedcoup by Antonio Tejero as recently as 1981. This is worth pondering whilst observing the implosion of Spain’seconomy. The decision for Europe’s bosses is this: they must ultimately confront theconsequences of their policy choices. They can destroy the eurozone by continuing with the same failed mix ofpolicies or by salvaging it by adding what has been missing from the outset: amechanism for shifting surpluses to the deficit regions in the form ofproductive investments(as opposed to handouts or loans). Turning stateslike Spain into sundrenched economic wastelands within the eurozone, andforcing the rest of the currency area into a debt-deflationary spiral, is amost efficient way of blowing up the whole system and possibly threatening thevery existence of Spanish liberal democracy itself.

Comments Off on The Elephant in the Room is Spain, Not Italy

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Tagged eu, euro crisis, greece, Italy, Marshall Auerback, spain

MMP #35 Functional Finance: A Conclusion

Let’sfinish up the discussion of Lerner’s functional finance approach addressing twoissues: functional finance and developing nations and also the functionalfinance approach to trade deficits.

Functional Finance and Developing Nations. Most of the developing nations havea sovereign currency—which means they can “afford” to buy whatever is for salein the domestic currency, including unemployed labor. As Lerner would put it,unemployment is evidence that there is an unmet demand for domestic currencythat can be filled by additional government spending. At the same time, manydeveloping nations have fixed or managed exchange rates that reduce domesticpolicy space to some degree. They can increase policy space either throughpolicies that generate foreign currency reserves (including development thatincreases exports), or they can protect foreign currency reserves throughcapital controls.

Inaddition, they can favour policy that leads to employment and developmentwithout increasing imports (import substitution policies, for example). Theycan create jobs programs that are labor intensive (so that foreign made capitalequipment is not needed) or programs that provide the output that the newlyemployed workers need (so that they do not spend their new incomes on imports).

Governmentcan favour domestic producers over foreign producers. It can limit itspurchases of foreign goods and services to export earnings. It can try to avoidborrowing in foreign currency in order to limit its need to devote foreigncurrency earnings to interest payments.

Asdiscussed, ability to impose and collect taxes can be impaired in a developingnation. This will limit government’s ability to directly command domesticoutput. And even if it finds plenty of unemployed labor willing to work for itscurrency, those workers might find it difficult to purchase output with thatcurrency at stable prices. More diligent tax collection will help to increasedemand for the currency (since taxes are paid in the domestic currency). Inaddition, government needs to focus job creation in those areas that will leadto increased production of the kinds of goods and services the new workers willwant to purchase. That can relieve inflationary pressures resulting from risingemployment.

For thelong run, avoiding foreign currency indebtedness and moving toward floatingexchange rates would be conducive to expansion of domestic policy space. Fullutilization of domestic resources (most importantly, labor) will allowdeveloping nations to maximize output while reducing inflation caused byinsufficient supply. Full employment of labor also provides many otherwell-known benefits that will not be detailed here.

A sovereigncurrency provides more policy space to government—it spends by crediting bankaccounts and thus is not subject to the budget constraint that applies to acurrency user. A floating exchange rate (or a managed rate with capitalcontrols) expands the policy space further—because the government does not needto accumulate sufficient reserves to maintain a peg. Well-planned use of thispolicy space will allow the government to move toward full employment withoutsetting off currency depreciation or domestic price inflation. To that end, theemployer of last resort or job guarantee model is particularly useful, a topicpursued in more detail elsewhere in the Primer.

Exports are a cost, Imports are a benefit. In real terms, exports are a costand imports are a benefit from the perspective of a nation as a whole. Theexplanation is simple. When resources including labor are used to produceoutput that is shipped to foreigners, the domestic population does not get toconsume that output, or use it for further production (in the case ofinvestment goods). The nation bears the cost of producing the output, but doesnot get the benefit. On the other hand, the importing nation gets the outputbut did not have to produce it. For this reason, in real terms net exports meannet costs; and net imports mean net benefits.

Now thereare several caveats. First, from the perspective of the producer of output, itdoes not matter who buys the produced goods or services—the firm is equallyhappy selling domestically or to foreign buyers. What the firm wants is to sellfor domestic currency in order to cover costs and reap profits. If the outputis sold domestically, the bank accounts of purchasers are debited, and theaccounts of the producing firm are credited. Everyone is happy. If the outputis sold to foreigners, the receipts will need to go through a currency exchangeso that the producer can receive domestic currency while the ultimatepurchasers are using their own currency. We will not concern ourselves with thedetails, but usually a domestic bank or the central bank will end up holdingreserves of the foreign currency (this will normally be a credit to a reserveaccount at the foreign central bank). The fact remains, however, that in termsof real resources, the “fruit of the labor” is enjoyed by foreigners when theoutput is exported, even though in financial terms the producing firm receivesa net credit to a bank account and the nation receives a net financial asset interms of foreign currency.

Second, netexports add to aggregate demand and increase measured GDP and national income.Jobs are created to produce goods and services for export. Hence, a nation thatwould otherwise operate below full employment can put resources to work in theexport sector. Wages and profits are generated, families receive incomes theywould not have received so that they are able to purchase consumption goods,and firms stay in business that otherwise might have gone bankrupt. This isprobably the main reason why governments encourage growth of exports. In themidst of the economic downturn, President Obama announced that his goal for theUS economy was to double its exports. This is a common strategy for nationsthat want to grow. However, note that for every export there must be an import;for every trade surplus there must be a trade deficit. Obviously it is notpossible for all countries to simultaneously grow in this manner—it isfundamentally a “beggar thy neighbour” strategy.

To theextent that resources are mobilized to produce for foreigners, the domesticpopulation does not receive any net real benefit. True, labor and otherresources that would have been left idle are now employed; workers who wouldnot have received a wage now get income; owners of firms who would not havesold output now receive profits. Yet, if the produced output is sent abroad,there is no extra output for domestic residents to purchase. What happens isthat existing output gets redistributed to these additional claimants—who nowhave wage and profit income. Thus, if we have only put unemployed resources towork in order to produce exports, there is no net benefit—the domesticpopulation is working “harder” but not consuming more in the aggregate becausethe “pie” available for the domestic population has not increased. Theredistribution process itself will probably require inflation as those who nowhave jobs compete for a piece of the pie, bidding up prices. To be sure, thiscould be a desirable social outcome—output gets redistributed from the “haves”to the “have-nots”, and putting unemployed people to work has numerous benefitsfor families and society as a whole (in terms of crime, family break-ups, andsocial cohesion).

But notethat this relied on the presumption that the nation had excess capacity tobegin with. If it had been operating at full capacity of labor, plant, andequipment, then it could only increase exports by reducing domesticconsumption, investment, or government use of resources. Labor and otherresources would be shifted from producing for domestic use toward satisfyingforeign demand for output. Clearly it would usually be preferable to achievefull employment by producing for domestic use rather than for export. Theadditional employment would provide both income as well as more output. Thedomestic “pie” would be larger, so that rather than redistributing from “haves”to “have-nots”, the newly employed would get pieces of the larger pie.

Anotherobvious caveat is that producing output for foreigners can be in a nation’seconomic and political interests. A nation might produce goods and servicesthat are sent abroad for humanitarian reasons—to aid in disaster relief, forexample. It might produce military supplies to aid allies. Foreign directinvestment could aid a developing country that might become a strategicpartner. And there is certainly no reason for a nation to balance its currentaccount on an annual basis—something that would be nearly impossible in ahighly globalized economy with international links in production processes.Hence we would not want to ignore various strategic reasons for exportingoutput and running trade surpluses.

We concludethat we should also take a “functional” approach to international trade: itmakes no more sense for a sovereign government that issues its own floatingcurrency to pursue a trade surplus than it does for that government to seek abudget surplus. Maximization of a current account surplus imposes net realcosts (given the caveats discussed above). Instead, it is best to pursue fullemployment at home, and let the current account and budget balances adjust.That is far better than the usual strategy—which is to pursue a trade surplusin order to get to full employment.

We now turnto a policy that will generate full employment at home. Next week: more on theemployer of last resort proposal.

Think Debtors Must Pay and Austerity is the Way?

(h/t Philip Pilkington)

Comments Off on Think Debtors Must Pay and Austerity is the Way?

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Uncategorized

US Employment Growth Shows Fiscal Policy Matters

US Q4 2011 GDP growth was slightly disappointing, and the mix was terrible as the growth was mostly due to inventories. I took issue with that report, arguing that the weakness was due to statistical distortions in the government spending data and the PCE services data. With that disappointing Q4 GDP report, expectations for quite weak economic growth in this year’s first half were encouraged.

But today’s employment data blows the weak consensus outlook out of the water. The economy created jobs at the fastest pace in nine months in January and the unemployment rate dropped to a near three-year low of 8.3 percent, indicating last quarter’s growth carried into early 2012.

Comments Off on US Employment Growth Shows Fiscal Policy Matters

Posted in Marshall Auerback

Tagged employment, labor department, Marshall Auerback, us q4 2011 gdp

Say W-h-a-a-t?

By Jon Krajack

This past week, in an ironic twist of fate, former Royal Bank of Scotland CEO Fred Goodwin was stripped of his Knighthood. Goodwin presided over RBS’s rapid growth leading up to the 2008 financial crises, but he retired suddenly, just a month before RBS reported roughly $35 billion in losses. Goodwin had been nicknamed “Fred the Shred” for his cost-cutting practices. With “Sir” being cut from Fred Goodwin’s official name, karma seems to have come full circle.

This past week, in an ironic twist of fate, former Royal Bank of Scotland CEO Fred Goodwin was stripped of his Knighthood. Goodwin presided over RBS’s rapid growth leading up to the 2008 financial crises, but he retired suddenly, just a month before RBS reported roughly $35 billion in losses. Goodwin had been nicknamed “Fred the Shred” for his cost-cutting practices. With “Sir” being cut from Fred Goodwin’s official name, karma seems to have come full circle. In testimony before the House Budget Committee, Chairman Bernanke warned that in order for the United States to ensure economic and financial stability, it must reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio over time. We wish the Chairman had warned against cutting the deficit during a balance sheet recession (while households are still trying to deleverage). We wish he had explained that countries that issue a non-convertible fiat currency, like the US, can allow their budgets to remain in deficit until the private sector finishes deleveraging (even if that means the debt/GDP ratio increases). We wish he had said that when private sector balance sheets have been repaired, the private sector will start spending again, the economy will begin to grow more rapidly, and the debt/GDP ratio will come down the RIGHT way.

In testimony before the House Budget Committee, Chairman Bernanke warned that in order for the United States to ensure economic and financial stability, it must reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio over time. We wish the Chairman had warned against cutting the deficit during a balance sheet recession (while households are still trying to deleverage). We wish he had explained that countries that issue a non-convertible fiat currency, like the US, can allow their budgets to remain in deficit until the private sector finishes deleveraging (even if that means the debt/GDP ratio increases). We wish he had said that when private sector balance sheets have been repaired, the private sector will start spending again, the economy will begin to grow more rapidly, and the debt/GDP ratio will come down the RIGHT way. Greece finds itself in a precarious situation. It has outstanding debts that it can not afford to repay. Fortunately, Germany has a “solution”! It’s simple: the Greek government should give up what little economic sovereignty they still have. More specifically, Greece should turn over it’s fiscal policy decisions to a euro zone budget commissioner that would have the power to veto budgetary proposals that are “not in line with targets set by international lenders.” If this occurs it will set a very dangerous world precedent:what’s the point of democracy and elections if public policy is in the hands ofinternational financiers?

Greece finds itself in a precarious situation. It has outstanding debts that it can not afford to repay. Fortunately, Germany has a “solution”! It’s simple: the Greek government should give up what little economic sovereignty they still have. More specifically, Greece should turn over it’s fiscal policy decisions to a euro zone budget commissioner that would have the power to veto budgetary proposals that are “not in line with targets set by international lenders.” If this occurs it will set a very dangerous world precedent:what’s the point of democracy and elections if public policy is in the hands ofinternational financiers?

This piece at The Economist talks about how recovery from the financial crises is going better in the United States than in Europe. They note that recovery in the United States has occurred against a backstop of loose fiscal policy. Further, they recognize that Europe has “been forced, or chosen” much tighter fiscal policy. What’s interesting here is that The Economist has the dots, but is failing to connect them. Maybe they should consider why it is that the United States is able to have looser fiscal policy?

This piece at The Economist talks about how recovery from the financial crises is going better in the United States than in Europe. They note that recovery in the United States has occurred against a backstop of loose fiscal policy. Further, they recognize that Europe has “been forced, or chosen” much tighter fiscal policy. What’s interesting here is that The Economist has the dots, but is failing to connect them. Maybe they should consider why it is that the United States is able to have looser fiscal policy?

David Cay Johnston is one of the few mainstream journalists that demonstrates an understanding of the difference between a currency issuer and a currency user. In this piece he explains that austerity will worsen economic recovery.

BREAKING NEWS! In order to prevent an election year debt ceiling debate, President Obama and congressional Republicans have reached an agreement. The president will sell his Burning Man tickets and donate the proceeds to help pay off the national debt. Some may argue that his Burning Man tickets will not even make a dent in the debt. Baby steps, folks. Baby steps.

BREAKING NEWS! In order to prevent an election year debt ceiling debate, President Obama and congressional Republicans have reached an agreement. The president will sell his Burning Man tickets and donate the proceeds to help pay off the national debt. Some may argue that his Burning Man tickets will not even make a dent in the debt. Baby steps, folks. Baby steps.

Charles Goodhart once served on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. In this piece, Goodhart explains why the Federal Reserve’s latest attempt to reveal its own expectations about the future path of short-term interest rates makes for fashionable theory but lousy policy.

Charles Goodhart once served on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. In this piece, Goodhart explains why the Federal Reserve’s latest attempt to reveal its own expectations about the future path of short-term interest rates makes for fashionable theory but lousy policy.